UN Special Procedures

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Special Procedure Mandate-Holders Presenting to the Third Committee

GA66 Third Committee Subject to change – Status as of 7 October 2011 Special procedure mandate-holders, Chairs of human rights treaty bodies or Chairs of Working Groups presenting reports Monday, 10 October (am) • Chair of the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women, Ms. Silvia Pimentel – oral report and interactive dialogue. • Special Rapporteur on violence against women, its causes and consequences, Ms. Rashida MANJOO report and interactive dialogue. Wednesday, 12 October (pm) • Chair of the Committee on the Rights of the Child, Mr. Jean Zermatten, – oral report. • Special Representative of the Secretary-General on violence against children, Ms. Marta SANTOS PAIS. • Special Rapporteur on the sale of children, child prostitution and child pornography, Ms. Najat M’jid MAALLA. Monday, 17 October (am) • Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights and fundamental freedoms of indigenous people, Mr. James ANAYA. Tuesday, 18 October (am) • Chair of the Committee against Torture, Mr. Claudio GROSSMAN – oral report and interactive dialogue. • Chair of the Subcommittee on Prevention of Torture, Mr. Malcolm David Evans – oral report and interactive dialogue. • Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment of punishment, Mr. Juan MENDEZ Wednesday, 19 October (pm) • Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Iran, Mr. Ahmed SHAHEED. • Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Myanmar, Mr. Tomas Ojea QUINTANA. • Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, Mr. Marzuki DARUSMAN. Thursday, 20 October (am) • Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in the Palestinian territories occupied since 1967, Mr. -

National Assembly

February 23, 2016 PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES 1 NATIONAL ASSEMBLY OFFICIAL REPORT Tuesday, 23rd February, 2016 The House met at 2.30 p.m. [The Speaker (Hon. Muturi) in the Chair] PRAYERS COMMUNICATION FROM THE CHAIR DISCHARGE OF MEMBERS FROM COMMITTEES Hon. Speaker: Hon. Members, I want to encourage you to pay attention to what is happening. Hon. Members, I have this Communication from the Chair which is on discharge of Members from Committees. I wish to report to the House that I am in receipt of a letter dated 16th February 2016, from the Minority Party Whip notifying me that the CORD Coalition has discharged the following Members from Committees: (i) Hon. Khatib Mwashetani, MP, who is discharged from the Departmental Committee on Environment and Natural Resources. (ii) Hon. Salim Idd Mustafa, MP, who is discharged from the Departmental Committee on Labour and Social welfare and the Joint Committee on Parliamentary Broadcasting and Library. He is the Vice-Chairperson of the latter Committee. (iii) Hon. Gideon Mung’aro, MP, who is discharged from the Departmental Committee on Lands. Hon. Members, the letter which is written pursuant to the provisions of Standing Order No. 176 also intends to discharge Hon. Khatib Mwashetani, MP, from the House Business Committee (HBC) and the Budget and Appropriations Committee. However, it is a fact that the Member for Lungalunga Constituency is not a Member of the HBC which was constituted by this House on 9th February 2016. You are also aware that the Budget and Appropriations Committee is yet to be reconstituted. This, therefore, implies that the intended discharge of the Member for Lungalunga from these two Committees was inadvertent. -

If Rio+20 Is to Deliver, Accountability Must Be at Its Heart

NATIONS UNIES UNITED NATIONS HAUT COMMISSARIAT DES NATIONS UNIES OFFICE OF THE UNITED NATIONS AUX DROITS DE L’HOMME HIGH COMMISSIONER FOR HUMAN RIGHTS PROCEDURES SPECIALES DU SPECIAL PROCEDURES OF THE CONSEIL DES DROITS DE L’HOMME HUMAN RIGHTS COUNCIL IF RIO+20 IS TO DELIVER, ACCOUNTABILITY MUST BE AT ITS HEART An Open Letter from Special Procedures mandate-holders of the Human Rights Council to States negotiating the Outcome Document of the Rio+20 Summit As independent experts of the Human Rights Council, we call on States to incorporate universally agreed international human rights norms and standards in the Outcome Document of the Rio+20 Summit with strong accountability mechanisms to ensure its implementation.1 The United Nations system has been building progressively our collective understanding of human rights and development through a series of key historical moments of international cooperation, from the adoption of the Universal Declaration on Human Rights in December 1948 to the Millennium Declaration in September 2000 that inspired the Millennium Development Goals to the and the World Summit Outcome Document in October 2005. Strategies based on the protection and realization of all human rights are vital for sustainable development and the practical effectiveness of our actions. A real risk exists that commitments made in Rio will remain empty promises without effective monitoring and accountability. We offer proposals as to how a double accountability mechanism can be established. At the international level, we support the proposal to establish a Sustainable Development Council to monitor progress towards the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) to be agreed by 2015. -

United Nations Juridical Yearbook, 2012

Extract from: UNITED NATIONS JURIDICAL YEARBOOK 2012 Part Two. Legal activities of the United Nations and related intergovernmental organizations Chapter III. General review of the legal activities of the United Nations and related intergovernmental organizations Copyright (c) United Nations CONTENTS v Page (b) Implementation agreement between the United Nations Industrial Development Organization, the United Nations Environment Pro- gramme and the Ministry of Environment and Sustainable Devel- opment of Côte d’Ivoire regarding the implementation of a project in Côte d’Ivoire entitled “Reducing mercury risks from artisanal and small scale gold mining (ASGM) in Côte d’Ivoire”, signed on 3, 19 and 26 October 2012 128 (c) Trust fund agreement between the United Nations Industrial De- velopment Organization and the Innovation and Industrial Devel- opment Fund, Republic of Armenia regarding the implementation of a project in Armenia entitled “Establishment of a Centre for International Industrial Cooperation (CIIC) in Armenia”, signed on 23 October and 5 November 2012 128 5 Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons Agreement between the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chem- ical Weapons (OPCW) and the Czech Republic on the Privileges and Immunities of the OPCW 129 Part Two. Legal activities of the United Nations and related intergovernmental organizations Chapter III General review of the legal activities of the United Nations and related intergovernmental organizations A General review of the legal activities of the United -

High Commissioner's Strategic Management Plan 2010-2011

High Commissioner’s Strategic Management Plan 2010-2011 High Commissioner’s Strategic Management Plan 2010-2011 The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this report do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Mission Statement The mission of the Office of the United Nations High General Assembly in resolution 48/141, the Charter Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) is to work of the United Nations, the Universal Declaration of for the promotion and protection of all human rights Human Rights and subsequent human rights for all people; to help empower people to realize instruments, the 1993 Vienna Declaration and their rights and to assist those responsible for Programme of Action, and the 2005 World Summit upholding such rights in ensuring that they are Outcome Document. implemented. In carrying out its mission OHCHR will: u Give priority to addressing the most pressing Operationally, OHCHR works with governments, human rights violations, both acute and chronic, legislatures, courts, national institutions, civil society, particularly those that put life in imminent peril. regional and international organizations, and the u Focus attention on those who are at risk and United Nations system to develop and strengthen vulnerable on multiple fronts. capacity, particularly at the national level, for the u Pay equal attention to the realization of civil, promotion and protection of human rights in cultural, economic, political, and social rights, accordance with international norms. -

United Nations Juridical Yearbook, 2010

Extract from: UNITED NATIONS JURIDICAL YEARBOOK 2010 Part Two. Legal activities of the United Nations and related intergovernmental organizations Chapter III. General review of the legal activities of the United Nations and related intergovernmental organizations Copyright (c) United Nations UNITED NATIONS JURIDICAL YEARBOOK 2010 Page (h) Exchange of letters extending the agreement between the United Nations Industrial Development Organization and the Govern- ment of Japan concerning the contribution by the Government of Japan to the UNIDO Investment and Technology Promotion Office Tokyo service aimed at promoting industrial investment in developing countries from 1 January 2011 to 31 December 2013, signed on 14 December 2010 . 86 7 International Atomic Energy Agency. 86 8 Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons Agreement between the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) and the Kingdom of Denmark on the Privi- leges and Immunities of the OPCW. 86 Part Two. Legal activities of the United Nations and related intergovernmental organizations Chapter III General review of the legal activities of the United Nations and related intergovernmental organizations A General review of the legal activities of the United Nations 1 Membership of the United Nations. 97 2 Peace and Security (a) Peacekeeping missions and operations . 97 (b) Political and peacebuilding missions. 104 (c) Other bodies . 110 (d) Missions of the Security Council . 111 (e) Other peace-related matters . 116 (f) Action of Member States authorized by the Security Council. 117 (g) Sanctions imposed under Chapter VII of the Charter of the Unit- ed Nations . 119 (h) Terrorism. 127 (i) Humanitarian law and human rights in the context of peace and security. -

Justice Under Siege: the Rule of Law and Judicial Subservience in Kenya

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law University at Buffalo School of Law Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law Journal Articles Faculty Scholarship 2001 Justice Under Siege: The Rule of Law and Judicial Subservience in Kenya Makau Mutua University at Buffalo School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.buffalo.edu/journal_articles Part of the Judges Commons, and the Rule of Law Commons Recommended Citation Makau Mutua, Justice Under Siege: The Rule of Law and Judicial Subservience in Kenya, 23 Hum. Rts. Q. 96 (2001). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.buffalo.edu/journal_articles/569 Copyright © 2001 The Johns Hopkins University Press. This article was first published in Human Rights Quarterly 23.1 (2001), 96–118. Reprinted with permission by Johns Hopkins University Press. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HUMAN RIGHTS QUARTERLY Justice Under Siege: The Rule of Law and Judicial Subservience in Kenya Makau Mutua* I. INTRODUCTION Constitutionalism and the rule of law are the central features of any political democracy that respects human rights. An independent judiciary, -

Appendix K. UN and Regional Special Procedures

Appendix K: UN and Regional Special Procedures Appendix K. UN and Regional Special Procedures UN Special Procedures Special Procedure Name Contact / Special instructions Independent Expert on minority Ms. Rita Izsák [email protected] issues Tel: +41 22 917 9640 Independent Expert on human Ms. Virginia Dandan [email protected] rights and international Telephone: (41-22) 928 9458 solidarity Fax: (+41-22) 928 9010 Independent Expert on the effects Mr. Cephas Lumina [email protected] of foreign debt Independent Expert on the issue Mr. John Knox [email protected] of human rights obligations relating to the enjoyment of a safe, clean, healthy and sustainable environment Independent Expert on the Mr. Alfred de Zayas [email protected] promotion of a democratic and equitable international order Independent Expert on the Mr. Shamsul Bari [email protected] situation of human rights in Somalia Independent Expert on the Mr. Mashood Baderin [email protected] situation of human rights in the Sudan Independent Expert on the Mr. Doudou Diène [email protected] situation of human rights in Côte d’Ivoire Independent Expert on the Mr. Gustavi Gallón [email protected] situation of human rights in Haiti Special Rapporteur in the field of Ms. Farida Shaheed [email protected] cultural rights Telephone: (41-22) 917 92 54 Special Rapporteur on adequate Ms. Raquel Rolnik [email protected] housing as a component of the right to an adequate standard of living Special Rapporteur on Mr. Mutuma Ruteere [email protected] contemporary forms of racism, racial discrimination, xenophobia and related intolerance Special Rapporteur on Ms. Gulnara Shahinian [email protected] contemporary forms of slavery, Special form: including its causes and its http://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Is consequences sues/Slavery/SR/AFslavery_en.do c K-1 Appendix K: UN and Regional Special Procedures Special Procedure Name Contact / Special instructions Special Rapporteur on Mr. -

Berichterstatter, Experten, Beauftragte Und Arbeitsgruppen Des Menschenrechtsrats (Stand: Juli 2013)

Übersichten | Berichterstatter des Menschenrechtsrats Berichterstatter, Experten, Beauftragte und Arbeitsgruppen des Menschenrechtsrats (Stand: Juli 2013) Thematische Mandate (30) Mandat Einrich- Derzeit tung Sonderberichterstatter über Menschenrechte und extreme Armut 1998 Maria Magdalena Sepúlveda Carmona, Chile Unabhängiger Experte für die Auswirkungen der Auslandsverschuldung und damit zusammenhängender internationaler finanzieller Verpflichtungen der Staaten auf den vollen Genuss aller Menschenrechte, insbesondere der wirtschaftlichen, sozialen 2000 Cephas Lumina, Sambia und kulturellen Rechte Sonderberichterstatter über das Recht auf Bildung 1998 Kishore Singh, Indien Sonderberichterstatter für die Menschenrechte Binnenvertriebener 2004 Chaloka Beyani, Sambia Sonderberichterstatter über Folter und andere grausame, unmenschliche oder erniedrigende Behandlung oder Strafe 1985 Juan Ernesto Mendez, Argentinien Sonderberichterstatterin über Gewalt gegen Frauen, deren Ursachen und deren Folgen 1994 Rashida Manjoo, Südafrika Sonderberichterstatter über die nachteiligen Auswirkungen der illegalen Verbrin- gung und Ablagerung toxischer und gefährlicher Stoffe und Abfälle auf den Genuss 1995 Marc Pallemaerts, Belgien der Menschenrechte Sonderberichterstatter über das Recht eines jeden auf das für ihn erreichbare Höchstmaß an körperlicher und geistiger Gesundheit 2002 Anand Grover, Indien Sonderberichterstatter über außergerichtliche, summarische oder willkürliche Hinrichtungen 1982 Christof Heyns, Südafrika Sonderberichterstatter für die -

Catalysts for Rights: the Unique Contribution of the UN’S Independent Experts on Human Rights

Foreign Policy October 2010 at BROOKINGS Catalysts for for Catalysts r ights: The Unique Contribution of the UN’s Independent Experts on Human Rights the UN’s of Unique Contribution The Catalysts for rights: The Unique Contribution of the UN’s Independent Experts on Human Rights TEd PiccoNE Ted Piccone BROOKINGS 1775 Massachusetts Ave, NW, Washington, DC 20036 www.brookings.edu Foreign Policy October 2010 at BROOKINGS Catalysts for rights The Unique Contribution of the U.N.’s Independent Experts on Human Rights Final Report of the Brookings Research Project on Strengthening U.N. Special Procedures TEd PiccoNE The views expressed in this report do not reflect an official position of The Brookings Institution, its Board, or Advisory Council members. © 2010 The Brookings Institution TABLE oF CoNTENTS acknowledgements . iii Members of Experts advisory group . v list of abbreviations . vi Executive summary ....................................................................... viii introduction . 1 Context . 2 Methodology . 3 A Short Summary of Special Procedures . 5 summary of findings . 9 Country Visits . .9 Follow-Up to Country Visits..............................................................19 Communications . 20 Resources . 31 Joint Activities and Coordination . .32 Code of Conduct . 34 Training . .34 Universal Periodic Review...............................................................35 Relationship with Treaty Bodies . 36 recommendations..........................................................................38 Appointments . 38 Country Visits and Communications .......................................................38 Follow-Up Procedures . 40 Resources . .41 Training . .41 Code of Conduct . 42 Relationship with UPR, Treaty Bodies, and other U.N. Actors . .42 appendices Appendix A HRC Resolution 5/1, the Institution Building Package ...........................44 Appendix B HRC Resolution 5/2, the Code of Conduct . .48 Appendix C Special Procedures of the HRC - Mandate Holders (as of 1 August 2010) . -

Third Committee Subject to Change – Status As of 20/10/08

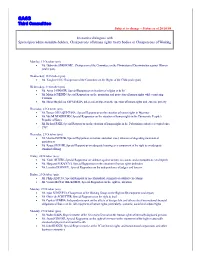

GA63 Third Committee Subject to change – Status as of 20/10/08 Interactive dialogues with Special procedure mandate-holders, Chairpersons of human rights treaty bodies or Chairpersons of Working Monday, 13 October (am) • Ms. Dubravka SIMONOVIC , Chairperson of the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (oral report) Wednesday, 15 October (pm) • Ms. Yanghee LEE, Chairperson of the Committee on the Rights of the Child (oral report) Wednesday, 22 October (pm) • Ms. Asma JAHANGIR, Special Rapporteur on freedom of religion or belief • Mr. Martin SCHEININ, Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of human rights while countering terrorism • Ms. Maria Magdalena SEPULVEDA, Independent Expert on the question of human rights and extreme poverty Thursday, 23 October (am) • Mr. Tomas OJEA QUINTANA , Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Myanmar • Mr. Vitit MUNTARBHORN, Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea • Mr. Richard FALK, Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in the Palestinian territories occupied since 1967 Thursday, 23 October (pm) • Mr. Manfred NOWAK, Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment • Ms. Raquel ROLNIK, Special Rapporteur on adequate housing as a component of the right to an adequate standard of living Friday, 24 October (am) • Ms. Yakin ERTÜRK, Special Rapporteur on violence against women, its causes and consequences (oral report) • Ms. Margaret SEKAGGYA, Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights defenders • Mr. Leandro DESPOUY , Special Rapporteur on the independence of judges and lawyers Friday, 24 October (pm) • Mr. Philip ALSTON , Special Rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions • Mr. -

The International Criminal Court's Cases in Kenya

AUGUST 2012 No. 237 Institute for Security Studies PAPER The International Criminal Court’s cases in Kenya: origin and impact INTRODUCTION Kenya’s new Constitution was promulgated in August On 23 January 2012, the fate of the six Kenyans accused 2010 after almost two decades of demands for by the International Criminal Court (ICC)’s Office of the constitutional change. These demands gained new Prosecutor (OTP) of committing crimes against humanity impetus as a result of the Kenya National Dialogue and was made known by the ICC’s Pre-Trial Chamber II (PTC Reconciliation (KNDR), the African Union (AU)-based II).1 Four of the six will be proceeding to trial in April 2013 in mediation process which ended the violence that followed two cases.2 The defence teams for all four accused the 2007 general elections.7 It is the KNDR that also requested leave to appeal from the PTC II on 30 January – eventually and indirectly – resulted in the cases being 2012. Leave was granted but their appeals were denied on brought before the ICC. Beyond creating the Grand 25 May 2012.3 Coalition Government, the KNDR aimed to address both The PTC II’s confirmation of the charges against the four the causes and consequences of the flawed presidential accused is particularly significant in that it represents the elections as well as the violence that followed.8 first ICC cases that will proceed to trial as a direct result of With that in mind – and in the context of the other legal, the OTP’s exercise of its own mandate4 – rather than on policy and institutional reforms either set in motion or the basis of a state referral or a UN Security Council ushered in by the KNDR to lessen the intensity of resolution as has previously been the case.5 competition for the presidency, and increase accountability Three scenarios pertained in advance of the PTC II’s for the political mobilisation of ethnicity in that competition decisions: The PTC II could have confirmed all charges and thus reduce elections-related violence – it is useful to against all six persons in the two cases.