Has Engaging in Party Coalitions Affected BSP Ideology? Jasjeet S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

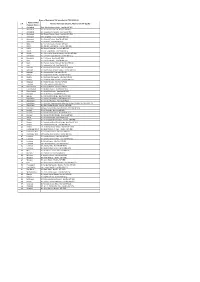

S N. Name of TAC/ Telecom District Name of Nominee [Sh./Smt./Ms

Name of Nominated TAC members for TAC (2020-22) Name of TAC/ S N. Name of Nominee [Sh./Smt./Ms] Hon’ble MP (LS/RS) Telecom District 1 Allahabad Prof. Rita Bahuguna Joshi, Hon’ble MP (LS) 2 Allahabad Smt. Keshari Devi Patel, Hon’ble MP (LS) 3 Allahabad Sh. Vinod Kumar Sonkar, Hon’ble MP (LS) 4 Allahabad Sh. Rewati Raman Singh, Hon’ble MP (RS) 5 Azamgarh Smt. Sangeeta Azad, Hon’ble MP (LS) 6 Azamgarh Sh. Akhilesh Yadav, Hon’ble MP (LS) 7 Azamgarh Sh. Rajaram, Hon’ble MP (RS) 8 Ballia Sh. Virendra Singh, Hon’ble MP (LS) 9 Ballia Sh. Sakaldeep Rajbhar, Hon’ble MP (RS) 10 Ballia Sh. Neeraj Shekhar, Hon’ble MP (RS) 11 Banda Sh. R.K. Singh Patel, Hon’ble MP (LS) 12 Banda Sh. Vishambhar Prasad Nishad, Hon’ble MP (RS) 13 Barabanki Sh. Upendra Singh Rawat, Hon’ble MP (LS) 14 Barabanki Sh. P.L. Punia, Hon’ble MP (RS) 15 Basti Sh. Harish Dwivedi, Hon’ble MP (LS) 16 Basti Sh. Praveen Kumar Nishad, Hon’ble MP (LS) 17 Basti Sh. Jagdambika Pal, Hon’ble MP (LS) 18 Behraich Sh. Ram Shiromani Verma, Hon’ble MP (LS) 19 Behraich Sh. Brijbhushan Sharan Singh, Hon’ble MP (LS) 20 Behraich Sh. Akshaibar Lal, Hon’ble MP (LS) 21 Deoria Sh. Vijay Kumar Dubey, Hon’ble MP (LS) 22 Deoria Sh. Ravindra Kushawaha, Hon’ble MP (LS) 23 Deoria Sh. Ramapati Ram Tripathi, Hon’ble MP (LS) 24 Faizabad Sh. Ritesh Pandey, Hon’ble MP (LS) 25 Faizabad Sh. Lallu Singh, Hon’ble MP (LS) 26 Farrukhabad Sh. -

Telangana State Election Commission

TELANGANA STATE ELECTION COMMISSION Recognized National Political Parties Sl. Symbols in Symbols Name of the Political Party No. English / Telugu Reserved Elephant 1 Bahujan Samaj Party ఏనుగు Lotus 2 Bharatiya Janata Party కమలం Ears of Corn & Sickle 3 Communist Party of India కంకి కొడవ젿 Hammer, Sickle & Star 4 Communist Party of India (Marxist) సుత్తి కొడవ젿 నక్షత్రం Hand 5 Indian National Congress చెయ్యి Clock 6 Nationalist Congress Party గడియారము Recognized State Parties in the State of Telangana Sl. Symbols in Name of the Party Symbols Reserved No. English / Telugu All India Majlis-E-Ittehadul- Kite 1 Muslimeen గా젿 పటం Car 2 Telangana Rastra Samithi కారు Bicycle 3 Telugu Desam Party స ైకిలు Yuvajana Sramika Rythu Ceiling Fan 4 Congress Party పంఖా Recognised State Parties in other States Sl. Symbols in Symbols Name of the Political Party No. English / Telugu Reserved Two Leaves All India Anna Dravida Munnetra 1 Kazhagam ర ండు ఆకులు Lion 2 All India Forward Bloc స ంహము A Lady Farmer 3 Janata Dal (Secular) Carrying Paddy వరి 롋పుతో ఉనన మహిళ Arrow 4 Janata Dal (United) బాణము Hand Pump 5 Rastriya Lok Dal చేత్త పంపు Banyan Tree 6 Samajwadi Party మరిి చెటటు Registered Political Parties with reserved symbol - NIL - TELANGANA STATE ELECTION COMMISSION Registered Political Parties without Reserved Symbol Sl. No. Name of the Political Party 1 All India Stree Shakthi Party 2 Ambedkar National Congress 3 Bahujan Samj Party (Ambedkar – Phule) 4 BC United Front Party 5 Bharateeya Bhahujana Prajarajyam 6 Bharat Labour Party 7 Bharat Janalok Party 8 -

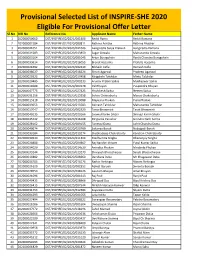

Provisional Selected List of INSPIRE-SHE 2020 Eligible For

Provisional Selected List of INSPIRE-SHE 2020 Eligible For Provisional Offer Letter Sl. -

Parliament of India R a J Y a S a B H a Committees

Com. Co-ord. Sec. PARLIAMENT OF INDIA R A J Y A S A B H A COMMITTEES OF RAJYA SABHA AND OTHER PARLIAMENTARY COMMITTEES AND BODIES ON WHICH RAJYA SABHA IS REPRESENTED (Corrected upto 4th September, 2020) RAJYA SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI (4th September, 2020) Website: http://www.rajyasabha.nic.in E-mail: [email protected] OFFICERS OF RAJYA SABHA CHAIRMAN Shri M. Venkaiah Naidu SECRETARY-GENERAL Shri Desh Deepak Verma PREFACE The publication aims at providing information on Members of Rajya Sabha serving on various Committees of Rajya Sabha, Department-related Parliamentary Standing Committees, Joint Committees and other Bodies as on 30th June, 2020. The names of Chairmen of the various Standing Committees and Department-related Parliamentary Standing Committees along with their local residential addresses and telephone numbers have also been shown at the beginning of the publication. The names of Members of the Lok Sabha serving on the Joint Committees on which Rajya Sabha is represented have also been included under the respective Committees for information. Change of nominations/elections of Members of Rajya Sabha in various Parliamentary Committees/Statutory Bodies is an ongoing process. As such, some information contained in the publication may undergo change by the time this is brought out. When new nominations/elections of Members to Committees/Statutory Bodies are made or changes in these take place, the same get updated in the Rajya Sabha website. The main purpose of this publication, however, is to serve as a primary source of information on Members representing various Committees and other Bodies on which Rajya Sabha is represented upto a particular period. -

NDTV Pre Poll Survey - U.P

AC PS RES CSDS - NDTV Pre poll Survey - U.P. Assembly Elections - 2002 Centre for the Study of Devloping Societies, 29 Rajpur Road, Delhi - 110054 Ph. 3951190,3971151, 3942199, Fax : 3943450 Interviewers Introduction: I have come from Delhi- from an educational institution called the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies (give your university’s reference). We are studying the Lok Sabha elections and are interviewing thousands of voters from different parts of the country. The findings of these interviews will be used to write in books and newspapers without giving any respondent’s name. It has no connection with any political party or the government. I need your co-operation to ensure the success of our study. Kindly spare some ime to answer my questions. INTERVIEW BEGINS Q1. Have you heard that assembly elections in U.P. is to be held in the next month? 2 Yes 1 No 8 Can’t say/D.K. Q2. Have you made up your mind as to whom you will vote during the forth coming elections or not? 2 Yes 1 No 8 Can’t say/D.K. Q3. If elections are held tomorrow it self then to whom will cast your vote? Please put a mark on this slip and drop it into this box. (Supply the yellow dummy ballot, record its number & explain the procedure). ________________________________________ Q4. Now I will ask you about he 1999 Lok Sabha elections. Were you able to cast your vote or not? 2 Yes 1 No 8 Can’t say/D.K. 9 Not a voter. -

E-Digest on Ambedkar's Appropriation by Hindutva Ideology

Ambedkar’s Appropriation by Hindutva Ideology An E-Digest Compiled by Ram Puniyani (For Private Circulation) Center for Study of Society and Secularism & All India Secular Forum 602 & 603, New Silver Star, Behind BEST Bus Depot, Santacruz (E), Mumbai: - 400 055. E-mail: [email protected], www.csss-isla.com Page | 1 E-Digest - Ambedkar’s Appropriation by Hindutva Ideology Preface Many a debates are raging in various circles related to Ambedkar’s ideology. On one hand the RSS combine has been very active to prove that RSS ideology is close to Ambedkar’s ideology. In this direction RSS mouth pieces Organizer (English) and Panchjanya (Hindi) brought out special supplements on the occasion of anniversary of Ambedkar, praising him. This is very surprising as RSS is for Hindu nation while Ambedkar has pointed out that Hindu Raj will be the biggest calamity for dalits. The second debate is about Ambedkar-Gandhi. This came to forefront with Arundhati Roy’s introduction to Ambedkar’s ‘Annihilation of Caste’ published by Navayana. In her introduction ‘Doctor and the Saint’ Roy is critical of Gandhi’s various ideas. This digest brings together some of the essays and articles by various scholars-activists on the theme. Hope this will help us clarify the underlying issues. Ram Puniyani (All India Secular Forum) Mumbai June 2015 Page | 2 E-Digest - Ambedkar’s Appropriation by Hindutva Ideology Contents Page No. Section A Ambedkar’s Legacy and RSS Combine 1. Idolatry versus Ideology 05 By Divya Trivedi 2. Top RSS leader misquotes Ambedkar on Untouchability 09 By Vikas Pathak 3. -

History of Uttar Pradesh

Uttar Pradesh at a glance Introduction Uttar Pradesh has multicultural, multiracial, fabulous wealth of nature-hills, valleys, rivers, forests, and vast plains. Viewed as the largest tourist destination in India, Uttar Pradesh boasts of 35 million domestic tourists. More than half of the foreign tourists, who visit India every year, make it a point to visit this state of Taj and Ganga. Agra itself receives around one million foreign tourists a year coupled with around twenty million domestic tourists. Uttar Pradesh is studded with places of tourist attractions across a wide spectrum of interest to people of diverse interests. The seventh most populated state of the world, Uttar Pradesh can lay claim to be the oldest seat of India's culture and civilization. It has been characterized as the cradle of Indian civilization and culture because it is around the Ganga that the ancient cities and towns sprang up. Uttar Pradesh played the most important part in India's freedom struggle and after independence it remained the strongest state politically. Geography Uttar Pradesh shares an international boundary with Nepal and is bordered by the Indian states of Uttarakhand, Himachal Pradesh, Mariana, Delhi, Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand and Bihar. The state can be divided into two distinct hypsographical (altitude) regions. The larger Gangetic Plain region is in the north; it includes the Ganges-Yamuna Doab, the Ghaghra plains, the Ganges plains and the Terai. It has fertile alluvial soil and a flat topography (with a slope of 2 m/km) broken by numerous ponds, lakes and rivers. The smaller Vindhya Hills and plateau region is in the south. -

Hindutva and Anti-Muslim Communal Violence in India Under the Bharatiya Janata Party (1990-2010) Elaisha Nandrajog Claremont Mckenna College

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont CMC Senior Theses CMC Student Scholarship 2010 Hindutva and Anti-Muslim Communal Violence in India Under the Bharatiya Janata Party (1990-2010) Elaisha Nandrajog Claremont McKenna College Recommended Citation Nandrajog, Elaisha, "Hindutva and Anti-Muslim Communal Violence in India Under the Bharatiya Janata Party (1990-2010)" (2010). CMC Senior Theses. Paper 219. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses/219 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you by Scholarship@Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in this collection by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CLAREMONT McKENNA COLLEGE HINDUTVA AND ANTI-MUSLIM COMMUNAL VIOLENCE IN INDIA UNDER THE BHARATIYA JANATA PARTY (1990-2010) SUBMITTED TO PROFESSOR RODERIC CAMP AND PROFESSOR GASTÓN ESPINOSA AND DEAN GREGORY HESS BY ELAISHA NANDRAJOG FOR SENIOR THESIS (Spring 2010) APRIL 26, 2010 2 CONTENTS Preface 02 List of Abbreviations 03 Timeline 04 Introduction 07 Chapter 1 13 Origins of Hindutva Chapter 2 41 Setting the Stage: Precursors to the Bharatiya Janata Party Chapter 3 60 Bharat : The India of the Bharatiya Janata Party Chapter 4 97 Mosque or Temple? The Babri Masjid-Ramjanmabhoomi Dispute Chapter 5 122 Modi and his Muslims: The Gujarat Carnage Chapter 6 151 Legalizing Communalism: Prevention of Terrorist Activities Act (2002) Conclusion 166 Appendix 180 Glossary 185 Bibliography 188 3 PREFACE This thesis assesses the manner in which India’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has emerged as the political face of Hindutva, or Hindu ethno-cultural nationalism. The insights of scholars like Christophe Jaffrelot, Ashish Nandy, Thomas Blom Hansen, Ram Puniyani, Badri Narayan, and Chetan Bhatt have been instrumental in furthering my understanding of the manifold elements of Hindutva ideology. -

India: the Weakening of the Congress Stranglehold and the Productivity Shift in India

ASARC Working Paper 2009/06 India: The Weakening of the Congress Stranglehold and the Productivity Shift in India Desh Gupta, University of Canberra Abstract This paper explains the complex of factors in the weakening of the Congress Party from the height of its power at the centre in 1984. They are connected with the rise of state and regional-based parties, the greater acceptability of BJP as an alternative in some of the states and at the Centre, and as a partner to some of the state-based parties, which are in competition with Congress. In addition, it demonstrates that even as the dominance of Congress has diminished, there have been substantial improvements in the economic performance and primary education enrolment. It is argued that V.P. Singh played an important role both in the diminishing of the Congress Party and in India’s improved economic performance. Competition between BJP and Congress has led to increased focus on improved governance. Congress improved its position in the 2009 Parliamentary elections and the reasons for this are briefly covered. But this does not guarantee an improved performance in the future. Whatever the outcomes of the future elections, India’s reforms are likely to continue and India’s economic future remains bright. Increased political contestability has increased focus on governance by Congress, BJP and even state-based and regional parties. This should ensure improved economic and outcomes and implementation of policies. JEL Classifications: O5, N4, M2, H6 Keywords: Indian Elections, Congress Party's Performance, Governance, Nutrition, Economic Efficiency, Productivity, Economic Reforms, Fiscal Consolidation Contact: [email protected] 1. -

The Gupta Empire: an Indian Golden Age the Gupta Empire, Which Ruled

The Gupta Empire: An Indian Golden Age The Gupta Empire, which ruled the Indian subcontinent from 320 to 550 AD, ushered in a golden age of Indian civilization. It will forever be remembered as the period during which literature, science, and the arts flourished in India as never before. Beginnings of the Guptas Since the fall of the Mauryan Empire in the second century BC, India had remained divided. For 500 years, India was a patchwork of independent kingdoms. During the late third century, the powerful Gupta family gained control of the local kingship of Magadha (modern-day eastern India and Bengal). The Gupta Empire is generally held to have begun in 320 AD, when Chandragupta I (not to be confused with Chandragupta Maurya, who founded the Mauryan Empire), the third king of the dynasty, ascended the throne. He soon began conquering neighboring regions. His son, Samudragupta (often called Samudragupta the Great) founded a new capital city, Pataliputra, and began a conquest of the entire subcontinent. Samudragupta conquered most of India, though in the more distant regions he reinstalled local kings in exchange for their loyalty. Samudragupta was also a great patron of the arts. He was a poet and a musician, and he brought great writers, philosophers, and artists to his court. Unlike the Mauryan kings after Ashoka, who were Buddhists, Samudragupta was a devoted worshipper of the Hindu gods. Nonetheless, he did not reject Buddhism, but invited Buddhists to be part of his court and allowed the religion to spread in his realm. Chandragupta II and the Flourishing of Culture Samudragupta was briefly succeeded by his eldest son Ramagupta, whose reign was short. -

The History of Punjab Is Replete with Its Political Parties Entering Into Mergers, Post-Election Coalitions and Pre-Election Alliances

COALITION POLITICS IN PUNJAB* PRAMOD KUMAR The history of Punjab is replete with its political parties entering into mergers, post-election coalitions and pre-election alliances. Pre-election electoral alliances are a more recent phenomenon, occasional seat adjustments, notwithstanding. While the mergers have been with parties offering a competing support base (Congress and Akalis) the post-election coalition and pre-election alliance have been among parties drawing upon sectional interests. As such there have been two main groupings. One led by the Congress, partnered by the communists, and the other consisting of the Shiromani Akali Dal (SAD) and Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). The Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) has moulded itself to joining any grouping as per its needs. Fringe groups that sprout from time to time, position themselves vis-à-vis the main groups to play the spoiler’s role in the elections. These groups are formed around common minimum programmes which have been used mainly to defend the alliances rather than nurture the ideological basis. For instance, the BJP, in alliance with the Akali Dal, finds it difficult to make the Anti-Terrorist Act, POTA, a main election issue, since the Akalis had been at the receiving end of state repression in the early ‘90s. The Akalis, in alliance with the BJP, cannot revive their anti-Centre political plank. And the Congress finds it difficult to talk about economic liberalisation, as it has to take into account the sensitivities of its main ally, the CPI, which has campaigned against the WTO regime. The implications of this situation can be better understood by recalling the politics that has led to these alliances. -

List of Successful Candidates

11 - LIST OF SUCCESSFUL CANDIDATES CONSTITUENCY WINNER PARTY Andhra Pradesh 1 Nagarkurnool Dr. Manda Jagannath INC 2 Nalgonda Gutha Sukender Reddy INC 3 Bhongir Komatireddy Raj Gopal Reddy INC 4 Warangal Rajaiah Siricilla INC 5 Mahabubabad P. Balram INC 6 Khammam Nama Nageswara Rao TDP 7 Aruku Kishore Chandra Suryanarayana INC Deo Vyricherla 8 Srikakulam Killi Krupa Rani INC 9 Vizianagaram Jhansi Lakshmi Botcha INC 10 Visakhapatnam Daggubati Purandeswari INC 11 Anakapalli Sabbam Hari INC 12 Kakinada M.M.Pallamraju INC 13 Amalapuram G.V.Harsha Kumar INC 14 Rajahmundry Aruna Kumar Vundavalli INC 15 Narsapuram Bapiraju Kanumuru INC 16 Eluru Kavuri Sambasiva Rao INC 17 Machilipatnam Konakalla Narayana Rao TDP 18 Vijayawada Lagadapati Raja Gopal INC 19 Guntur Rayapati Sambasiva Rao INC 20 Narasaraopet Modugula Venugopala Reddy TDP 21 Bapatla Panabaka Lakshmi INC 22 Ongole Magunta Srinivasulu Reddy INC 23 Nandyal S.P.Y.Reddy INC 24 Kurnool Kotla Jaya Surya Prakash Reddy INC 25 Anantapur Anantha Venkata Rami Reddy INC 26 Hindupur Kristappa Nimmala TDP 27 Kadapa Y.S. Jagan Mohan Reddy INC 28 Nellore Mekapati Rajamohan Reddy INC 29 Tirupati Chinta Mohan INC 30 Rajampet Annayyagari Sai Prathap INC 31 Chittoor Naramalli Sivaprasad TDP 32 Adilabad Rathod Ramesh TDP 33 Peddapalle Dr.G.Vivekanand INC 34 Karimnagar Ponnam Prabhakar INC 35 Nizamabad Madhu Yaskhi Goud INC 36 Zahirabad Suresh Kumar Shetkar INC 37 Medak Vijaya Shanthi .M TRS 38 Malkajgiri Sarvey Sathyanarayana INC 39 Secundrabad Anjan Kumar Yadav M INC 40 Hyderabad Asaduddin Owaisi AIMIM 41 Chelvella Jaipal Reddy Sudini INC 1 GENERAL ELECTIONS,INDIA 2009 LIST OF SUCCESSFUL CANDIDATE CONSTITUENCY WINNER PARTY Andhra Pradesh 42 Mahbubnagar K.