You Can Read It Here

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HANSARD 17-22 DEBATES and PROCEEDINGS Speaker

HANSARD 17-22 DEBATES AND PROCEEDINGS Speaker: Honourable Kevin Murphy Published by Order of the Legislature by Hansard Reporting Services and printed by the Queen's Printer. Available on INTERNET at http://nslegislature.ca/index.php/proceedings/hansard/ First Session MONDAY, OCTOBER 23, 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE PRESENTING REPORTS OF COMMITTEES: Law Amendments Committee, Hon. M. Furey ....................................................................................................1559 INTRODUCTION OF BILLS: No. 58, Workers’ Compensation Act, Ms. T. Martin .....................................................................................................1561 No. 59, Health Authorities Act, Ms. E. Smith-McCrossin....................................................................................1561 STATEMENTS BY MEMBERS: Springhill Bump: 59th Anniv. - Commemorate, Hon. J. Baillie ....................................................................................................1561 HMCS Kootenay Day: 48th Anniv. - Acknowledge, Mr. B. Jessome ...................................................................................................1562 Saunders, Clive/Lydia: 60th Wed. Anniv. - Congrats., Ms. K. Masland ..................................................................................................1562 2 Flu Season (2017) - Vaccinate, Hon. L. Diab ......................................................................................................1563 Soc. of Atl. Heroes: Fundraising Success - Congrats., Ms. B. Adams -

HANSARD 19-59 DEBATES and PROCEEDINGS Speaker

HANSARD 19-59 DEBATES AND PROCEEDINGS Speaker: Honourable Kevin Murphy Published by Order of the Legislature by Hansard Reporting Services and printed by the Queen's Printer. Available on INTERNET at http://nslegislature.ca/index.php/proceedings/hansard/ Second Session FRIDAY, OCTOBER 18, 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE TABLING REPORTS, REGULATIONS AND OTHER PAPERS: Involuntary Psychiatric Treatment Act, Ann. Rpt. 2018-19, Hon. R. Delorey .................................................................................................4399 GOVERNMENT NOTICES OF MOTION: Res. 1355, Persons Case: Women as Senior Ldrs. in Pub. Serv. - Recog., Hon. K. Regan....................................................................................................4400 Vote - Affirmative..................................................................................4400 Res. 1356, YWCA: Wk. Without Violence - Recog., Hon. K. Regan....................................................................................................4400 Vote - Affirmative..................................................................................4401 INTRODUCTION OF BILLS: No. 207, Protection for Persons in Care Act, B. Adams............................................................................................................4401 No. 208, Health Protection Act, Susan Leblanc ....................................................................................................4401 No. 209, Clothesline Act, L. Roberts ...........................................................................................................4401 -

September 27, 2017 Honourable Karen Casey Nova Scotia Minister

www.nsgeu.ca [email protected] September 27, 2017 Honourable Karen Casey Nova Scotia Minister of Finance PO Box 187, 1723 Hollis St., Halifax NS B3J 2N3 [email protected] Dear Minister Casey: Re: Marijuana Legalization Following your meeting last June with Canada’s other Ministers of Finance where the issue of marijuana legalization was discussed you stated, "That is really the priority for the three ministers right now — to look at how we do that consultation, when we do it and what questions we ask, what information we want to hear from the public." In preparation for this consultation, the Nova Scotia Government and General Employees Union has commissioned a report, A Public Health Approach to Cannabis Legalization, to critically assess the public health literature pertaining to cannabis distribution and retail from a public health perspective. I am pleased to share that report with you. To protect public health in Nova Scotia as cannabis legalization moves forward, it’s important to design a strong distribution and retail format guided by the best available public health evidence. With primary distribution options ranging from privatized to a publicly owned system, the decision regarding how to distribute cannabis should involve weighing public health protection motivations versus promoting private commercial interests. As you will see, researchers and public health professionals are clear: implementing a publicly owned system for cannabis distribution and retail is the best way to protect public health, whereas a privatized system may put public health at risk. In short, if Nova Scotia owns it, Nova Scotia controls it. You can choose to prioritize public health or commercial interests. -

October 8, 2013 Nova Scotia Provincial General

47.1° N 59.2° W Cape Dauphin Point Aconi Sackville-Beaver Bank Middle Sackville Windsor μ Alder Junction Point Sackville-Cobequid Waverley Bay St. Lawrence Lower Meat Cove Capstick Sackville Florence Bras d'Or Waverley- North Preston New Waterford Hammonds Plains- Fall River- Lake Echo Aspy Bay Sydney Mines Dingwall Lucasville Beaver Bank Lingan Cape North Dartmouth White Point South Harbour Bedford East Cape Breton Centre Red River Big Intervale Hammonds Plains Cape North Preston-Dartmouth Pleasant Bay Bedford North Neils Harbour Sydney Preston Gardiner Mines Glace Bay Dartmouth North South Bar Glace Bay Burnside Donkin Ingonish Minesville Reserve Mines Ingonish Beach Petit Étang Ingonish Chéticamp Ferry Upper Marconi Lawrencetown La Pointe Northside- Towers Belle-Marche Clayton Cole Point Cross Victoria-The Lakes Westmount Whitney Pier Park Dartmouth Harbour- Halifax Sydney- Grand Lake Road Grand Étang Wreck Cove St. Joseph Leitches Creek du Moine West Portland Valley Eastern Shore Whitney Timberlea Needham Westmount French River Fairview- Port Morien Cap Le Moine Dartmouth Pier Cole Balls Creek Birch Grove Clayton Harbour Breton Cove South Sydney Belle Côte Kingross Park Halifax ^ Halifax Margaree Harbour North Shore Portree Chebucto Margaree Chimney Corner Beechville Halifax Citadel- Indian Brook Margaree Valley Tarbotvale Margaree Centre See CBRM Inset Halifax Armdale Cole Harbour-Eastern Passage St. Rose River Bennet Cape Dauphin Sable Island Point Aconi Cow Bay Sydney River Mira Road Sydney River-Mira-Louisbourg Margaree Forks Egypt Road North River BridgeJersey Cove Homeville Alder Point North East Margaree Dunvegan Englishtown Big Bras d'Or Florence Quarry St. Anns Eastern Passage South West Margaree Broad Cove Sydney New Waterford Bras d'Or Chapel MacLeods Point Mines Lingan Timberlea-Prospect Gold Brook St. -

Hansard 18-17 Debates And

HANSARD 18-17 DEBATES AND PROCEEDINGS Speaker: Honourable Kevin Murphy Published by Order of the Legislature by Hansard Reporting Services and printed by the Queen's Printer. Available on INTERNET at http://nslegislature.ca/index.php/proceedings/hansard/ Second Session THURSDAY, OCTOBER 4, 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE TABLING REPORTS, REGULATIONS AND OTHER PAPERS: PSC - Moving Toward Equity/Objectif: l’équité (2017-2018), Hon. T. Ince .......................................................................................................1253 IPTA - Ann. Rpt. (2017-2018), Hon. R. Delorey .................................................................................................1254 GOVERNMENT NOTICES OF MOTION: Res. 492, Diversity: Employee Commitment - Thanks, Hon. T. Ince .......................................................................................................1254 Vote - Affirmative..................................................................................1255 Res. 493, Blomidon Estate Winery: Contrib. to Indus. - Recog., Hon. K. Colwell .................................................................................................1255 Vote - Affirmative..................................................................................1256 Res. 494, Coldwell, Mickey: Preserv. Gaspereau River: Recog., Hon. K. Colwell .................................................................................................1256 Vote - Affirmative..................................................................................1257 -

HANSARD 19-55 DEBATES and PROCEEDINGS Speaker

HANSARD 19-55 DEBATES AND PROCEEDINGS Speaker: Honourable Kevin Murphy Published by Order of the Legislature by Hansard Reporting Services and printed by the Queen's Printer. Available on INTERNET at http://nslegislature.ca/index.php/proceedings/hansard/ Second Session FRIDAY, OCTOBER 11, 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE PRESENTING AND READING PETITIONS: Govt. (N.S.): Breast Prosthesis: MSI Coverage - Ensure, Hon. K. Regan....................................................................................................4081 GOVERNMENT NOTICES OF MOTION: Res. 1317, Dixon, Kayley: Prov. Volun. of the Yr. - Commend, The Premier ........................................................................................................4082 Vote - Affirmative..................................................................................4083 Res. 1318, Intl. Day of the Girl Child: Women in Finance, Ldrs. - Recog., Hon. K. Casey ....................................................................................................4083 Vote - Affirmative..................................................................................4084 Res. 1319, Dobson, Sarah/Evans, Grace: 50 Women MLAs Proj. - Congrats., Hon. K. Regan....................................................................................................4084 Vote - Affirmative..................................................................................4085 Res. 1320, Maintenance Enforcement Prog.: Reducing Arrears - Recog., Hon. M. Furey ....................................................................................................4085 -

Hansard 20-68 Debates And

HANSARD 20-68 DEBATES AND PROCEEDINGS Speaker: Honourable Kevin Murphy Published by Order of the Legislature by Hansard Reporting Services and printed by the Queen's Printer. Available on INTERNET at http://nslegislature.ca/index.php/proceedings/hansard/ Second Session FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 21, 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE SPEAKER’S RULING: Particular use of “misrepresenting” is unparliamentary. (Pt. of order by S. Leblanc [Hansard p. 5199, 20 February 2020]) No point of order ....................................................................................5207 PRESENTING REPORTS OF COMMITTEES Veterans Affairs Committee, 2019 Ann. Rpt., R. DiCostanzo ....................................................................................................5208 GOVERNMENT NOTICES OF MOTION Res. 1674, Social Enterprise Week: Assisting Those with Diverse Abilities - Recog., The Premier ........................................................................................................5209 Vote - Affirmative..................................................................................5209 Res. 1675, Pictou Co. Rivers Assoc: Promoting Sport Fishing - Recog., Hon. K. Colwell .................................................................................................5209 Vote - Affirmative..................................................................................5210 Res. 1676, Glen Haven Manor: Supporting Immigration - Recog., Hon. L. Metlege Diab ........................................................................................5210 -

Provincial Legislatures

PROVINCIAL LEGISLATURES ◆ PROVINCIAL & TERRITORIAL LEGISLATORS ◆ PROVINCIAL & TERRITORIAL MINISTRIES ◆ COMPLETE CONTACT NUMBERS & ADDRESSES Completely updated with latest cabinet changes! 88 / PROVINCIAL RIDINGS PROVINCIAL RIDINGS British Columbia Saanich South .........................................Lana Popham ....................................100 Shuswap..................................................George Abbott ....................................95 Total number of seats ................85 Skeena.....................................................Robin Austin.......................................95 Liberal..........................................49 Stikine.....................................................Doug Donaldson .................................97 New Democratic Party ...............35 Surrey-Cloverdale...................................Kevin Falcon.......................................97 Independent ................................1 Surrey-Fleetwood ...................................Jaqrup Brar..........................................96 Surrey-Green Timbers ............................Sue Hammell ......................................97 Abbotsford South....................................John van Dongen ..............................101 Surrey-Newton........................................Harry Bains.........................................95 Abbotsford West.....................................Michael de Jong..................................97 Surrey-Panorama ....................................Stephanie Cadieux -

Ref.: NSE LCC Threshold TP2014 (21 Pages) To: Hon. (Prof.) Randy Delorey, Minister, Nova Scotia Environment Dept Cc (All Rt

Soil & Water Conservation Society of Metro Halifax (SWCSMH) 310-4 Lakefront Road, Dartmouth, NS, Canada B2Y 3C4 Email: [email protected] Tel: (902) 463-7777 Master Homepage: http://lakes.chebucto.org Ref.: NSE_LCC_Threshold_TP2014 (21 pages) To: Hon. (Prof.) Randy Delorey, Minister, Nova Scotia Environment Dept Cc (all Rt. Hon. Stephen McNeil, Hon. Diana C. Whalen, Hon. Andrew Younger, Hon. Lena MLAs w/in Metlege Diab, Hon. Keith Colwell, Hon. Tony Ince, Hon. Kelly Regan, Hon. Joanne the HRM Bernard, Hon. Labi Kousoulis, Hon. Kevin Murphy, Hon. Maureen MacDonald, Hon. area): Denise Peterson-Rafuse, Hon. Dave Wilson, Mr. Allan Rowe, Mr. Stephen Gough, Mr. Brendan Maguire, Mr. Bill Horne, Ms. Patricia Arab, Mr. Ben Jessome, Mr. Iain Rankin, Mr. Joachim Stroink, Ms. Joyce Treen From: S. M. Mandaville Post-Grad Dip., Professional Lake Manage. Chairman and Scientific Director Date: March 14, 2014 Subject: Phosphorus:- Details on LCC (Lake Carrying Capacity)/Threshold values of lakes, and comparison with artificially high values chosen by the HRM We are an independent scientific research group with some leading scientists across Canada and the USA among our membership. Written informally. I provide web scans where necessary as backup to Government citations. Pardon any typos/grammar. T-o-C: Subject/Topic Page #s Overview 2 Introduction 2 Eutrophication 4 Potential sources of phosphorus 4 CCME (Canadian Council of Ministers of the Environment)’s guidance 5 table --- --- Conclusions of the 18-member countries of the OECD (Organization for -

Riding by Riding-Breakdown

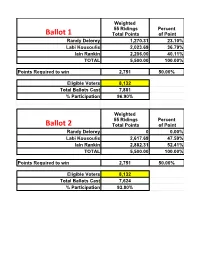

Weighted 55 Ridings Percent Total Points of Point Randy Delorey 1,270.31 23.10% Labi Kousoulis 2,023.69 36.79% Iain Rankin 2,206.00 40.11% TOTAL 5,500.00 100.00% Points Required to win 2,751 50.00% Eligible Voters 8,132 Total Ballots Cast 7,881 % Participation 96.90% Weighted 55 Ridings Percent Total Points of Point Randy Delorey 0 0.00% Labi Kousoulis 2,617.69 47.59% Iain Rankin 2,882.31 52.41% TOTAL 5,500.00 100.00% Points Required to win 2,751 50.00% Eligible Voters 8,132 Total Ballots Cast 7,624 % Participation 93.80% DISTRICT Candidate Final Votes Points 01 - ANNAPOLIS Randy DELOREY 31 26.5 01 - ANNAPOLIS Labi KOUSOULIS 34 29.06 01 - ANNAPOLIS Iain RANKIN 52 44.44 01 - ANNAPOLIS Total 117 100 Candidate Final Votes Points 02 - ANTIGONISH Randy DELOREY 176 53.01 02 - ANTIGONISH Labi KOUSOULIS 35 10.54 02 - ANTIGONISH Iain RANKIN 121 36.45 02 - ANTIGONISH Total 332 100 Candidate Final Votes Points 03 - ARGYLE Randy DELOREY 37 41.11 03 - ARGYLE Labi KOUSOULIS 24 26.67 03 - ARGYLE Iain RANKIN 29 32.22 03 - ARGYLE Total 90 100 Candidate Final Votes Points 04 - BEDFORD BASIN Randy DELOREY 92 34.72 04 - BEDFORD BASIN Labi KOUSOULIS 100 37.74 04 - BEDFORD BASIN Iain RANKIN 73 27.55 04 - BEDFORD BASIN Total 265 100 Candidate Final Votes Points 05 - BEDFORD SOUTH Randy DELOREY 116 39.59 05 - BEDFORD SOUTH Labi KOUSOULIS 108 36.86 05 - BEDFORD SOUTH Iain RANKIN 69 23.55 05 - BEDFORD SOUTH Total 293 100 Candidate Final Votes Points 06 - CAPE BRETON CENTRE - WHITNEY PIER Randy DELOREY 11 12.36 06 - CAPE BRETON CENTRE - WHITNEY PIER Labi KOUSOULIS 30 33.71 06 - CAPE BRETON CENTRE - WHITNEY PIER Iain RANKIN 48 53.93 06 - CAPE BRETON CENTRE - WHITNEY PIER Total 89 100 Candidate Final Votes Points 07 - CAPE BRETON EAST Randy DELOREY 22 19.47 07 - CAPE BRETON EAST Labi KOUSOULIS 32 28.32 07 - CAPE BRETON EAST Iain RANKIN 59 52.21 07 - CAPE BRETON EAST Total 113 100 Candidate Final Votes Points 08 - CHESTER - St. -

HANSARD 17-30 DEBATES and PROCEEDINGS Speaker

HANSARD 17-30 DEBATES AND PROCEEDINGS Speaker: Honourable Kevin Murphy Published by Order of the Legislature by Hansard Reporting Services and printed by the Queen's Printer. Available on INTERNET at http://nslegislature.ca/index.php/proceedings/hansard/ First Session MONDAY, MARCH 5, 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE PRESENTING REPORTS OF COMMITTEES: Law Amendments Committee, Hon. M. Furey ....................................................................................................2449 Law Amendments Committee, Hon. M. Furey ....................................................................................................2450 GOVERNMENT NOTICES OF MOTION: Res. 916, Vieau, Shane (Dartmouth) - Academy Award: Best Production Design - Congrats., Hon. L. Glavine .................................................................2450 Vote - Affirmative..................................................................................2451 STATEMENTS BY MEMBERS: Island View H.S. Enhancement Comm.: Fundraising Efforts - Thank, Ms. B. Adams ......................................................................................2451 Campbell, Peter: PGA Tour (China) - Success Recognize, Mr. K. Bain ........................................................................................................2451 Horne, Dr. Gabrielle: Vindication - Acknowledge, Ms. L. Roberts....................................................................................................2452 2 Saint Mary’s University Bangladeshi Students’ Soc.: Bangladeshi Night (4th -

A Pandemic Budget

www.policymagazine.ca March—April 2021 Canadian Politics and Public Policy A Pandemic Budget $6.95 Volume 9 – Issue 2 Essential to the Economy Serving exporters, importers, retailers, farmers and manufacturers, CN’s transportation services are integral to modern life, touching the lives of millions of Canadians every day. $250B 25% WORTH OF GOODS OF WHAT WE TRANSPORT TRANSPORTED IS EXPORTED 24,000 $3B RAILROADERS CAPITAL INVESTMENTS (2021) cn.ca Everyone has the right to live free from harm and discrimination. That’s why the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples is so important. Contact your Member of Parliament and urge them to support the quick passage of Bill C-15. Learn more at SupportUNDRIP.ca CanadianIn ThisPolitics Issue and Pu2b lic FromPoli cythe Editor / L. Ian MacDonald A Pandemic Budget Canadian Politics and 3 Kevin Page, Donya Ashnaei and Elo Mamoh Public Policy Canada’s Debt Narrative, from Financial Crisis to Pandemic EDITOR AND PUBLISHER L. Ian MacDonald 6 Kevin Page, Donya Ashnaei and Elo Mamoh [email protected] Fiscal Policy: Relief, Recovery and Reset ASSOCIATE EDITOR Jeremy Leonard and Angel Talavera Lisa Van Dusen 9 [email protected] Letter from London: Avoiding Austerity II in the EU CONTRIBUTING WRITERS Kevin Lynch and Paul Deegan Thomas S. Axworthy, 11 Andrew Balfour, Yaroslav Baran, The Great Budgetary Pivot: But to Where? James Baxter, Derek H. Burney, Shachi Kurl Catherine Cano, Stéphanie Chouinard, 16 Margaret Clarke, Rachel Curran, The Mood of Canada: People, the Pandemic