The Supreme Court of India: an Empirical Overview*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Recruitment Record of Batch 2008-2013 (1).Pdf

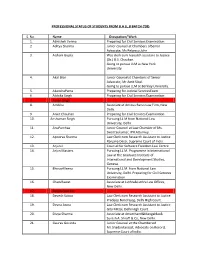

PROFESSIONAL STATUS OF STUDENTS FROM B.A LL.B BATCH (‘08) S. No. Name Occupation/ Work 1. Abhishek Verma Preparing for Civil Services Examination 2. Aditya Sharma Junior counsel at Chambers ofSenior Advocate, Ms Rebecca John 3. Aishani Gupta Was clerk cum research assistant to Justice (Dr.) B.S. Chauhan. Going to pursue LLM at New York University. 4. Akal Brar Junior Counselat Chambers of Senior Advocate, Mr Amit Sibal. Going to pursue LLM at Berkley University. 5. AkanshaPama Preparing for Judicial ServicesExam 6. Alokika Singh Preparing for Civil Services Examination 7. Aman Singh 8. Ambika Associate at Amicus Rarus Law Firm, New Delhi. 9. Ankit Chauhan Preparing for Civil Services Examination 10. Anshuman Singh Pursuing LL.M from National Law University, Delhi. 11. AnuParchaa Junior Counsel at Law Chamber of Ms. Swati Sukumar, IPR Attorney. 12. Apoorva Sharma Law Clerk cum Research Assistant to Justice Ranjana Desai, Supreme Court of India. 13. Arjun J. Counsel for Software Freedom Law Centre 14. Arjun Masters Pursuing LL.M. Programme in International Law at the Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies, Geneva. 15. BhinavMeena Pursuing LL.M. from National Law University, Delhi. Preparing for Civil Services Examination 16. CharuRawat Associate at Luthra&Luthra Law Offices, New Delhi. 17. DeeptiGautam 18. Devesh Saboo Law Clerk cum Research Assistant to Justice Pradeep Nandrajog, Delhi High Court. 19. Devna Arora Law Clerk cum Research Assistant to Justice Gita Mittal, Delhi High Court. 20. Divya Sharma Associate at Amarchand&Mangaldas& Suresh A. Shroff & Co, New Delhi. 21. Gaurav Govinda Junior Counsel at the Chambersof Mr.ShadanFarasat, Advocate on Record, Supreme Court of India. -

Water Resource English Cover-2019-20.Cdr

A Panoramic View of Krishna Raja Sagara Dam, Karnataka GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF JAL SHAKTI DEPARTMENT OF WATER RESOURCES RIVER DEVELOPMENT AND GANGA REJUVENATION NEW DELHI ANNUAL REPORT 2019-20 GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF JAL SHAKTI DEPARTMENT OF WATER RESOURCES RIVER DEVELOPMENT AND GANGA REJUVENATION NEW DELHI Content Sl. No. CHAPTER PAGE NO. 1. OVERVIEW 1-14 2. WATER RESOURCES SCENARIO 17-20 3. MAJOR PROGRAMMES 23-64 4. INTER-STATE RIVER ISSUES 67-71 5. INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION 75-81 6. EXTERNAL ASSISTANCE IN WATER RESOURCES SECTOR 85-96 7. ORGANISATIONS AND INSTITUTIONS 99-170 8. PUBLIC SECTOR ENTERPRISES 173-184 9. INITIATIVES IN NORTH EAST 187-194 10. ADMINISTRATION, TRAINING AND GOVERNANACE 197-202 11. TRANSPARENCY 205 12. ROLE OF WOMEN IN WATER RESOURCES MANAGEMENT 206 13. PROGRESSIVE USE OF HINDI 207-208 14. STAFF WELFARE 211-212 15. VIGILANCE 213 16. APPOINTMENT OF PERSONS WITH SPECIAL NEEDS 214 Annexures Sl. No. ANNEXURES PAGE NO. I. ORGANISATION CHART 217 II. STAFF IN POSITION AS ON 31.12.2019 218 III. LIST OF NAMES & ADDRESSES OF SENIOR OFFICERS & HEADS 219-222 OF ORGANISATIONS UNDER THE DEPARTMENT IV. BUDGET AT GLANCE 223-224 V. 225-226 COMPLETED/ ALMOST COMPLETED LIST OF PRIORITY PROJECTS (AIBP WORKS) REPORTED VI. CENTRAL ASSISTANCE & STATE SHARE DURING RELEASED 227 PMKSY 2016-20 FOR AIBP WORKS FOR 99 PRIORITY PROJECTS UNDER VII. CENTRAL ASSISTANCE & STATE SHARE RELEASED DURING 228 UNDER PMKSY 2016-20 FOR CADWM WORKS FOR 99 PRIORITY PROJECTS VIII. 229 UNDER FMP COMPONENT OF FMBAP STATE/UT-WISE DETAILS OF CENTRAL ASSISTANCE RELEASED IX. -

State of Uttaranchal Vs. Balwant Singh Chaufal & Ors. on 18 January

State Of Uttaranchal Vs. Balwant Singh Chaufal & Ors. on 18 January, 2010 Supreme Court of India State Of Uttaranchal Vs. Balwant Singh Chaufal & Ors. on 18 January, 2010 Bench: Dalveer Bhandari, Mukundakam Sharma IN THE SUPREME COURT OF INDIA CIVIL APPELLATE JURISDICTION CIVIL APPEAL NOS.1134-1135 OF 2002 State of Uttaranchal .. Appellant Versus Balwant Singh Chaufal & Others .. Respondents J U D G M E N T Dalveer Bhandari, J. 1. These appeals have been filed by the State of Uttaranchal (now Uttarakhand) against the orders dated 12.7.2001 and 1.8.2001 passed by the Division Bench of the High Court of Uttaranchal at Nainital in Civil Miscellaneous Writ Petition No. 689 (M/B) of 2001. 2. The appointment of L. P. Nathani was challenged before the High Court in a Public Interest Litigation on the ground that he could not hold the august Office of the Advocate General of Uttarakhand in view of Article 165 read with Article 217 of the Constitution. According to the respondent, Mr. Nathani was ineligible to be appointed as the Advocate General because he had attained the age of 62 years much before he was appointed as the Advocate General. The High Court entertained the petition and directed the State Government to take decision on the issue raised within 15 days and apprise the same to the High Court. 3. The State of Uttaranchal preferred special leave petitions before this Court on 6.8.2001. This Court vide order dated 9.8.2001 stayed the operation of the impugned judgment of the High Court. -

2010 Vol.V Issue No.3 July

COURT NEWS Vol V, Issue No. 3 July-September, 2010 EDITORIAL BOARD Hon'ble Mr. Justice Altamas Kabir, Judge, Supreme Court of India Hon'ble Mr. Justice Dalveer Bhandari, Judge, Supreme Court of India COMPILED BY A.I.S. Cheema, Secretary General, Supreme Court of India Bibhuti Bhushan Bose, Asstt. Editor, Supreme Court Reports A quarterly newsletter published by Supreme Court of India, New Delhi Also available on website: www.supremecourtofindia.nic.in LIST OF SUPREME COURT JUDGES S.No. Name of the Hon'ble Judge Date of Date of Appointment Retirement 01. Hon'ble Mr. Justice S.H. Kapadia, 18-12-2003 29-09-2012 Chief Justice of India (CJI) As CJI: 12-05-2010 02. Hon'ble Mr. Justice Altamas Kabir 09-09-2005 19-07-2013 03. Hon’ble Mr. Justice R.V. Raveendran 09-09-2005 15-10-2011 04. Hon’ble Mr. Justice Dalveer Bhandari 28-10-2005 01-10-2012 05. Hon’ble Mr. Justice D.K. Jain 10-04-2006 25-01-2013 06. Hon’ble Mr. Justice Markandey Katju 10-04-2006 20-09-2011 07. Hon’ble Mr. Justice H.S. Bedi 12-01-2007 05-09-2011 08. Hon’ble Mr. Justice V.S. Sirpurkar 12-01-2007 22-08-2011 09. Hon’ble Mr. Justice B. Sudershan Reddy 12-01-2007 08-07-2011 10. Hon’ble Mr. Justice P. Sathasivam 21-08-2007 27-04-2014 11. Hon’ble Mr. Justice G.S. Singhvi 12-11-2007 12-12-2013 12. Hon’ble Mr. Justice Aftab Alam 12-11-2007 19-04-2013 13. -

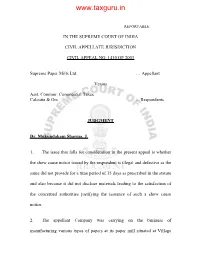

The Issue That Falls for Consideration in the Present Appeal Is

www.taxguru.in REPORTABLE IN THE SUPREME COURT OF INDIA CIVIL APPELLATE JURISDICTION CIVIL APPEAL NO. 1410 OF 2003 Supreme Paper Mills Ltd. … Appellant Versus Asst. Commnr. Commercial Taxes Calcutta & Ors ... Respondents JUDGMENT Dr. Mukundakam Sharma, J. 1. The issue that falls for consideration in the present appeal is whether the show cause notice issued by the respondent is illegal and defective as the same did not provide for a time period of 15 days as prescribed in the statute and also because it did not disclose materials leading to the satisfaction of the concerned authorities justifying the issuance of such a show cause notice. 2. The appellant Company was carrying on the business of manufacturing various types of papers at its paper mill situated at Village www.taxguru.in Raninagar Chakdah, District Nadia, Kolkata. In the course of its carrying on business it filed necessary returns as required under the Bengal Finance (Sales Tax) Act, 1941 (for short the “1941 Act”) and also paid the taxes on the basis of the said return. The Revenue also completed the assessment proceeding which was deemed to have been made under Section 11 E (1) of the 1941 Act by operation of law. Subsequently, however, the appellant received a show cause notice from the Deputy Commissioner, Commercial Taxes, Corporate Division whereby the appellant was directed to show cause why deemed assessment case for the period mentioned in the said impugned notices would not be re-opened. Since the validity of the aforesaid notices has been challenged by the appellant herein, we would extract the relevant contents of one of the notices which reads as follows:- “Whereas I am satisfied that the returns filed by you which formed the basis of the above mentioned deemed assessment case exhibit incorrect statement of your turnover/incorrect particulars of sales whereas it appears to me that the assessment is required to be re- opened, you are hereby directed to show cause on 29.6.99 at 11.00 a.m. -

Judges of the Supreme Court: a Regional Analysis

5 NOVEMBER 2016 JUDGES OF THE SUPREME COURT: A REGIONAL ANALYSIS The Supreme Court of India started Indian Constitution, inter-state disputes or functioning on January 28, 1950 from the important questions of law; it is also the final Chamber of Princes in the Parliament House, forum for many statutory appeals, deciding the seat of the erstwhile Federal Court. individual disputes on facts. Inaugurated just two days after India’s The judges of the Supreme Court of India Constitution was adopted and the nation became a sovereign, democratic republic, the have played a significant role in shaping Supreme Court shifted to its present building Indian democracy, the Indian Constitution at Tilak Marg in 1958. itself and the umpteen laws which govern the country. Commencing with eight judges, the Besides being the highest Constitutional court strength of the Court was steadily raised and which can be moved directly under Article 32 currently stands at 31. against the violation of fundamental rights, the Supreme Court is also the highest appellate court of the country. In this compilation, I bring out the data As it stands today, the Supreme Court of India regarding the parent High Courts of the is not just deciding and interpreting the judges of the Supreme Court. The parent High (C) BAR & BENCH !1 5 NOVEMBER 2016 Court of a judge is the High Court to which judges. Out of these two hundred and twenty- the concerned judge was first elevated to the four judges, forty-three were appointed as the Bench. Chief Justice of India. The judges have been divided into two Barring seven judges, who were directly categories for the purpose of this piece – elevated from the Bar, the remaining two puisne judges and Chief Justice of India. -

Weekly One Liners 19Th of August to 25St of August 2019

Weekly One Liners 19th of August to 25th of August 2019 Weekly One Liners 19th of August to 25st of August 2019 National Sports Award 2019 National Affairs Selection Committee for the Sports Awards 2019 has The Union Minister of Human Resource Development announced the National Sports Awards 2019. National inaugurated the International Conference titled Sports Awards are given every year to recognize and “Journey of Teacher Education: Local to Global” in New reward excellence in sports. The awardees will receive Delhi. Sports Minister Kiren Rijiju and former India football their awards from the President of India at a specially captain Baichung Bhutia flagged off Op-Blue Freedom. organized function at the Rashtrapati Bhawan. This is an initiative in which a group of armed forces Selection Committee for the Sports Awards 2019 was veterans train sports enthusiasts in survival training headed by Justice Mukundakam Sharma, Retired Judge, and self-defence. Supreme Court. NISHTHA (National Initiative for School Heads and Apart from a medal and a citation, Rajiv Gandhi Khel Teachers Holistic Advancement) is the training Ratna Awardee will receive a cash prize of Rs. 7.5 lakh. programme to improve Learning Outcomes at the Arjuna, Dronacharya and Dhyan Chand Awardees will Elementary level across the country. This is the largest receive statuettes, certificates and cash prize of Rs. 5 teachers’ training programme of its kind in the world. lakh each. A trophy and citation is given to the entity in Amazon has opened its largest campus in the world in the Rashtriya Khel Protsahan Puruskar, 2019. Recipients Hyderabad. Union Government is planning to launch an e-commerce of Rashtriya Khel Protsahan Puruskar will be given portal named “Bharatcraft” for MSME’s. -

Manju Ram Kalita Vs State of Assam on 29 May, 2009

Manju Ram Kalita vs State Of Assam on 29 May, 2009 Supreme Court of India Manju Ram Kalita vs State Of Assam on 29 May, 2009 Author: . B Chauhan Bench: Mukundakam Sharma, B.S. Chauhan Reporta IN THE SUPREME COURT OF INDIA CRIMINAL APPELLATE JURISDICTION CRIMINAL APPEAL NO. 299 OF 2003 Dr. B.S. Chauhan, J. 1. This Appeal has been preferred against the Judgment and Order dated 21st December, 2001 of the High Court of Gauhati in Criminal Revision (P) No. 578 of 2000 by which the High Court concurred with the finding of facts, recorded by the Trial Court dated 22.12.1999 passed by the Addl. Chief Judicial Magistrate, Kamrup, Guwahati in Case No. G.R.1957/1997; and of the Appellate Court, the Sessions Judge, Kamrup dated 13.10.2000 passed in Criminal Appeal No.3 of 2000 that the appellant was guilty of committing the offences under Sections 494 and 498A of the Indian Penal Code (in short "I.P.C") and sentenced him to undergo rigorous imprisonment for 2 years u/S 498A and for 3 years u/S 494 I.P.C. However, both the sentences were directed to run concurrently. 2. The facts and circumstances giving rise to this appeal are that the appellant, a Government servant, got married with Smt. Minati Das (Kalita), the complainant on 5.2.1992 as per Hindu rites. Smt. Minati Das (Kalita) gave birth to a male child on 10.3.1993. However, the relationship between the husband and wife were not cordial as it was alleged by the wife that she was being tortured mentally and physically by the Appellant. -

In the Supreme Court of India Civil Appellate Jurisdiction

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF INDIA CIVIL APPELLATE JURISDICTION CIVIL APPEAL NO. 1922 OF 2011 (Arising out of SLP(C)No.14065 of 2008) UNION OF INDIA & ORS. ... APPELLANT(S) VERSUS NRIPEN SARMA ... RESPONDENT(S) O R D E R Leave granted. We have heard learned Additional Solicitor General and learned counsel for the respondent. This appeal emanates from the judgment of the Division Bench of the Gauhati High Court (High Court of Assam, Nagaland, Meghalaya, Manipur, Tripura, Mizoram & Arunachal Pradesh) in Misc. Case No.1569 of 2007 in W.A.No.72020 of 2006. The appeal filed by the Union of India was dismissed by the High Court because of inordinate delay of 239 days. The Division Bench of the High Court, while dismissing the appeal, has observed as under : “We have gone through the contents of the petition. The delay occurred because of the respondents took their own sweet time to reach the conclusion whether the judgment should be appealed or not. It is not that they were prevented by any reason which is beyond their control to take such a decision in time. Even otherwise, on merits of the case also it does not appear to have any tenable ground of appeal. In the circumstances, we do not see any merits in this petition.” We have also gone through the condonation of delay application which was filed in the High Court. In our considered view, the High Court was fully justified in dismissing the appeal : 2 : on the ground of delay because no sufficient cause was shown for condoning the delay. -

1 Spotlaw SUPREME COURT of INDIA Supreme

SUPREME COURT OF INDIA Supreme Paper Mills Ltd. Vs. Asst.Commnr.Commercialtaxes Calcutta C.A.No.1410 of 2003 (D.K. Jain, Dr. Mukundakam Sharma and R.M. Lodha JJ.) 25.03.2010 JUDGEMENT Dr.Mukundakam Sharma, J. 1. The issue that falls for consideration in the present appeal is whether the show cause notice issued by the respondent is illegal and defective as the same did not provide for a time period of 15 days as prescribed in the statute and also because it did not disclose materials leading to the satisfaction of the concerned authorities justifying the issuance of such a show cause notice. 2. The appellant Company was carrying on the business of manufacturing various types of papers at its paper mill situated at Village Raninagar Chakdah, District Nadia, Kolkata. In the course of its carrying on business it filed necessary returns as required under the Bengal Finance (Sales Tax) Act, 1941 (for short the "1941 Act") and also paid the taxes on the basis of the said return. The Revenue also completed the assessment proceeding which was deemed to have been made under Section 11 E (1) of the 1941 Act by operation of law. Subsequently, however, the appellant received a show cause notice from the Deputy Commissioner, Commercial Taxes, Corporate Division whereby the appellant was directed to show cause why deemed assessment case for the period mentioned in the said impugned notices would not be re-opened. Since the validity of the aforesaid notices has been challenged by the appellant herein, we would extract the relevant contents of one of the notices which reads as follows:- "Whereas I am satisfied that the returns filed by you which formed the basis of the above mentioned deemed assessment case exhibit incorrect statement of your turnover/incorrect particulars of sales whereas it appears to me that the assessment is required to be re- opened, you are hereby directed to show cause on 29.6.99 at 11.00 a.m. -

Decided by the Hon'ble Supreme

From the Editor Desk...... At the outset I on behalf of Delhi Legal Services Authority wish the readers and patrons of Nyaya Kiran.. A Happy New Year and Colourful Holi. The new issue of Nyaya Kiran is in your hands and we have tried to incorporate all whatever has happened in this quarter from January to March, 2008 in this edition. Delhi Legal Services Authority has organized a talk on the Indian Experiments for Improving “Access to Justice” at Tis Hazari Court which was highly successful and the key-note address in the said conference was delivered by Sh. Marc Galanter a renowned Professor of Law (U.S.A) and expert on Indian Legal System. The two-day Training Programme on Protection of Women from Domestic Violence was organized by Delhi Legal Services Authority at V.K. Krishna Menon Bhavan on 2nd & 3rd February, 2008 and Booklet on Report & Recommendations on Domestic Violence was released by Hon’ble Mr. Justice Ashok Bhan, Judge, Supreme Court of India. The interactive session of the programme was quite useful and the participants interacted quite freely with the distinguished guests and speakers and were suitably guided by the distinguished speakers. In the month of March, a function was organized in Tihar Complex on 11th of March, 2008 commemorating the International Women’s Day and a Booklet “UMEED” was released by Dr. Girija Vyas entailing details of women prisoners and the children accompanying them in the august presence of Hon’ble the Chief Justice & Patron-in-Chief , Delhi Legal Services Authority ; Hon’ble Executive Chairman, Delhi Legal Services Authority and other Hon’ble Judges from the High Court, Ms. -

English Passed Away

CONTENTS TNPSC BITS ..................................................................................................................................... 10 TAMIL NADU .................................................................................................................................... 17 AL Somayaji .............................................................................................. 17 Thiyaa and Ezhava community ................................................................. 17 100th year of Bharathi speech .................................................................. 17 Renaming Chennai Metro stations ............................................................ 17 Sa Kandasamy ........................................................................................... 18 Amma Platinum plus health scheme .......................................................... 19 Economic Growth of Tamilnadu ................................................................ 19 Chief Minister’s Special Award .................................................................. 20 Amma Covid 19 home care scheme ........................................................... 22 Jal Jeevan Mission Review ........................................................................ 22 Turmeric under ‘one district, one product’ scheme ................................... 22 MUDRA loan scheme Rank ........................................................................ 23 NATIONAL ........................................................................................................................................