Adam's Genesis Game

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Poetry: Grades 7 & 8

1 Poetry: Grades 7 & 8 Barter Casey at the Bat The Creation The Crucifixion The Destruction of Sennacherib Do not go gentle into that good night From “Endymion,” Book I Forgetfulness The Highwayman The House on the Hill If The Listeners Love (III) The New Colossus No Coward Soul Is Mine One Art On His Blindness On Turning Ten Ozymandias Paul Revere's Ride The Road Goes Ever On (from The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings) Sonnet Spring and Fall Stanzas th th South Texas Christian Schools Speech Meet 2019-2020 7 - 8 Grade Poetry 2 The Tide Rises, the Tide Falls The Village Blacksmith The World th th South Texas Christian Schools Speech Meet 2019-2020 7 - 8 Grade Poetry 3 Barter Sara Teasdale Life has loveliness to sell, All beautiful and splendid things, Blue waves whitened on a cliff, Soaring fire that sways and sings, And children's faces looking up Holding wonder in a cup. Life has loveliness to sell, Music like a curve of gold, Scent of pine trees in the rain, Eyes that love you, arms that hold, And for your spirit's still delight, Holy thoughts that star the night. Spend all you have for loveliness, Buy it and never count the cost; For one white singing hour of peace Count many a year of strife well lost, And for a breath of ecstasy Give all you have been, or could be. † th th South Texas Christian Schools Speech Meet 2019-2020 7 - 8 Grade Poetry 4 Casey at the Bat Ernest Lawrence Thayer The outlook wasn’t brilliant for the Mudville nine that day: The score stood four to two, with but one inning more to play, And then when Cooney died at first, and Barrows did the same, A pall-like silence fell upon the patrons of the game. -

The Lonely Society? Contents

The Lonely Society? Contents Acknowledgements 02 Methods 03 Introduction 03 Chapter 1 Are we getting lonelier? 09 Chapter 2 Who is affected by loneliness? 14 Chapter 3 The Mental Health Foundation survey 21 Chapter 4 What can be done about loneliness? 24 Chapter 5 Conclusion and recommendations 33 1 The Lonely Society Acknowledgements Author: Jo Griffin With thanks to colleagues at the Mental Health Foundation, including Andrew McCulloch, Fran Gorman, Simon Lawton-Smith, Eva Cyhlarova, Dan Robotham, Toby Williamson, Simon Loveland and Gillian McEwan. The Mental Health Foundation would like to thank: Barbara McIntosh, Foundation for People with Learning Disabilities Craig Weakes, Project Director, Back to Life (run by Timebank) Ed Halliwell, Health Writer, London Emma Southgate, Southwark Circle Glen Gibson, Psychotherapist, Camden, London Jacqueline Olds, Professor of Psychiatry, Harvard University Jeremy Mulcaire, Mental Health Services, Ealing, London Martina Philips, Home Start Malcolm Bird, Men in Sheds, Age Concern Cheshire Opinium Research LLP Professor David Morris, National Social Inclusion Programme at the Institute for Mental Health in England Sally Russell, Director, Netmums.com We would especially like to thank all those who gave their time to be interviewed about their experiences of loneliness. 2 Introduction Methods A range of research methods were used to compile the data for this report, including: • a rapid appraisal of existing literature on loneliness. For the purpose of this report an exhaustive academic literature review was not commissioned; • a survey completed by a nationally representative, quota-controlled sample of 2,256 people carried out by Opinium Research LLP; and • site visits and interviews with stakeholders, including mental health professionals and organisations that provide advice, guidance and services to the general public as well as those at risk of isolation and loneliness. -

Master Thesis Project Artificial Intelligence Adaptation in Video

Master Thesis Project Artificial Intelligence Adaptation in Video Games Author: Anastasiia Zhadan Supervisor: Aris Alissandrakis Examiner: Welf Löwe Reader: Narges Khakpour Semester: VT 2018 Course Code: 4DV50E Subject: Computer Science Abstract One of the most important features of a (computer) game that makes it mem- orable is an ability to bring a sense of engagement. This can be achieved in numerous ways, but the most major part is a challenge, often provided by in-game enemies and their ability to adapt towards the human player. How- ever, adaptability is not very common in games. Throughout this thesis work, aspects of the game control systems that can be improved in order to be adapt- able were studied. Based on the results gained from the study of the literature related to artificial intelligence in games, a classification of games was de- veloped for grouping the games by the complexity of the control systems and their ability to adapt different aspects of enemies behavior including individual and group behavior. It appeared that only 33% of the games can not be con- sidered adaptable. This classification was then used to analyze the popularity of games regarding their challenge complexity. Analysis revealed that simple, familiar behavior is more welcomed by players. However, highly adaptable games have got competitively high scores and excellent reviews from game critics and reviewers, proving that adaptability in games deserves further re- search. Keywords: artificial intelligence in games, adaptability in games, non-player character adaptation, challenge Preface Computer games have become an interest for me not so long ago, but since then they have turned almost into a true passion. -

Human-Level AI's Killer Application: Interactive Computer Games

AI Magazine Volume 22 Number 2 (2001) (© AAAI) Articles Human-Level AI’s Killer Application Interactive Computer Games John E. Laird and Michael van Lent I Although one of the fundamental goals of AI is to communication with natural language, com- understand and develop intelligent systems that monsense reasoning, creativity, and learning. have all the capabilities of humans, there is little If this is our dream, why isn’t any progress active research directly pursuing this goal. We pro- being made? Ironically, one of the major rea- pose that AI for interactive computer games is an sons that almost nobody (see Brooks et al. emerging application area in which this goal of [2000] for one high-profile exception) is work- human-level AI can successfully be pursued. Inter- active computer games have increasingly complex ing on this grand goal of AI is that current and realistic worlds and increasingly complex and applications of AI do not need full-blown intelligent computer-controlled characters. In this human-level AI. For almost all applications, article, we further motivate our proposal of using the generality and adaptability of human interactive computer games for AI research, review thought is not needed—specialized, although previous research on AI and games, and present more rigid and fragile, solutions are cheaper the different game genres and the roles that and easier to develop. Unfortunately, it is human-level AI could play within these genres. We unclear whether the approaches that have then describe the research issues and AI techniques been developed to solve specific problems are that are relevant to each of these roles. -

STS145 Paper

STS145 Paper - From Populous to Dungeon Keeper A Tale of God Games Po-Wen Joseph Huang 3/15/2001 Introduction Computer game design houses can usually be categorized into two types: the ones who follow the existing ideas and the ones consistently creating games that set new benchmarks or even creating new genres along the way. The company Bullfrog belongs to the second category. In the late 1980s, Bullfrog released a game called Populous that signified the beginning of a new genre that had tremendous impact on the computer industry still in its infancy. The genre was later referred to as God games. The basic concept of God games is simple - the gamers can decide the fate of the followers by changing terrains and cast magic that may cause catastrophe. The ultimate goal is usually to make followers thrive and to defeat followers of the other gods (the competitors). Bullfrog subsequently released many God games with different variations such as Powermonger, Magic Carpet, and Dungeon Keeper. Peter Molyneux, the founder of Bullfrog, was the person responsible for the creation of Populous. He created many award winning games during his years at Bullfrog and Dungeon Keeper was his last game designed before he left Bullfrog. Dungeon Keeper was a game that challenged the traditional idea that players are heroes in games. Electronic Arts, after acquiring Bullfrog, published the game in 1997. It was a good example of God game as well as a perfect example of the conflicting goals between game designers wanting to produce a 'perfect' game and business people who need to look after their shareholders' interests. -

Playing Games with Technology: Fictions of Science in the Civilization Series Will Slocombe, University of Liverpool

Playing Games with Technology: Fictions of Science in the Civilization Series Will Slocombe, University of Liverpool Introduction Videogames might be thought to be too recent, and to concerned with entertainment, to reveal appropriately historicised attitudes to technology. However, as this essay will demonstrate, there is value in considering how one type of game, the “4X strategy” game, encodes particular assumptions about technology and its development. Although closely affiliated to the “God game” (a videogame in which the player is given absolute, and often supernatural power over a civilization or tribe’s development), “4X strategy” games are defined by the phrase “EXplore, EXpand, EXploit and EXterminate”. That is, such games encourage players to “explore” the in-game environment, “expand” their civilizations, “exploit” the resources of their civilization’s territory, and “exterminate” rival civilizations. Whilst this phrasing is loaded, it provides a sense of the kind of activities within the game, although it does not foreground the importance of technological research. Using the Civilization series of videogames (six games and various “expansions” over the period 1991- 2016) as an exemplar, this article asserts that “technology trees”, as the underpinning structural element of such many 4X strategy games, reveal not only a specific cultural attitude to technology, but also towards the history of technology. Whilst this essay will describe and examine “technology trees” later, it is important to realise at the outset that these -

Modul Mengatasi Kecanduan Permainan Daring Elektronik (Pde Disorder)

MODUL MENGATASI KECANDUAN PERMAINAN DARING ELEKTRONIK (PDE DISORDER) LAYANAN BIMBINGAN SOSIAL BAGI SISWA KATA PENGANTAR Segala puji syukur penyusun panjatkan kehadirat Allah SWT atas segala rahmat dan hidayahNya, sehingga penyusun dapat menyelesaikan modul tentang Mengatasi Kecanduan Permainan Daring Elelktronik (Online Game Disorder) dengan baik. Harapan penyusun semoga degan adanya modul ini, membantu bagi para siswa khususnya mengenal dan memahami berbagai macam jenis permainan eleltronik dengan dampak- dampak yang ditimbulkannya. Akhir kata denngan segala kerendahan hati penyusun ucappkan kepada semua pihak atas egala bantuan dan dukungan yang telah diberikan dalam penyusunan modul ini. Penyusun menyadari masih jauuh dari sempurna, meskipun demikian semoga dapat bermanfaat bagi semua pihak. DAFTAR ISI KATA PENGANTAR ................................................................................. DAFTAR ISI................................................................................................. PENDAHULUAN......................................................................................... BAB IMENGENAL BEBAGAI MACAM GAME...................................... BAB II DAMPAK POSITIF GAME........................................................... a. Gme Membuat Orang Pintar b. Game Meningkatan Konsentrasi c. Ketajaman mata yang lebih cepat. d. Meningkatkan kinerja otak dan memacu otak dalam menerima cerita. e. Meningkatkan kemampuan membaca. f. BAB III DAMPAK NEGATIF GAME....................................................... -

Quantum of Solace Pc System Requirements

Quantum Of Solace Pc System Requirements Edwin usually mongrelized resistingly or publicise grubbily when Tory Manny reprieves glaringly and dynamically. Transformable Gabriello gibber that bluebells haggles degenerately and averaging hourlong. Earthquaking Edmund reassesses explicitly, he constrict his Franck very unexpectedly. How to integrate my wireles controller, all that either explode upon shooting adventure game that part of skeleton signals but saying that is a fairly good considering the requirements of quantum solace pc system and It is heaven first Treyarch game a be released on the PC and it catch a double. Half the ruthless world of the requirements are the image with old friends and use the. James Bond 007 Quantum of Solace Repack Size 3 Gb Original Size 60 GB Genre Action Adventure. Download pc game can i would work. 007 Quantum of Solace is important another Bond request that hopes to recapture the series. Running games on your PC VistaXPW7 System requirements To test if every game still work on. Bong in quantum of system requirements! Check box example Correct last name 007 Quantum of Solace 244 007. Berkeley electronic press. Quantum of Solace first-person present shooter PC game depending on movies The experience starts with Wayne Connection kidnapping Mr. Call the Duty 5 FAQS COD Modding & Mapping Wiki. Playing as of solace is also keenly aware of the requirements lab on collecting data in captcha below have achievements and the file. James Bond 007 Quantum of Solace Free Download. Community Sledgehammer Games. Please stand by treyarch has come with. Quantum of solace game free download My blog. -

The Lonely Page

The Lonely Page Edited by Emily DeDakis © eSharp 2011 eSharp University of Glasgow Glasgow G12 8QQ http://www.gla.ac.uk/esharp © eSharp 2011 No reproduction of any part of this publication is permitted without the written permission of eSharp eSharp The Lonely Page Contents Introduction 5 Emily DeDakis, editor (Queen’s University Belfast) Suicide, solitude and the persistent scraping 10 Shauna Busto Gilligan (NUI Maynooth/ University of Glamorgan) Game: A media for modern writers to learn from? 20 Richard Simpson (Liverpool John Moores University) Imaginary ledgers of spectral selves: A blueprint of 29 existence Christiana Lambrinidis (Centre for Creative Writing & Theatre for Conflict Resolution, Greece) ‘The writing is the thing’: Reflections on teaching 36 creative writing Micaela Maftei (University of Glasgow) The solitude room 47 Cherry Smyth (University of Greenwich) How critical reflection affects the work of the writer 55 Ellie Evans (Bath Spa University) Beyond solitude: A poet’s and painter’s collaboration 66 Stephanie Norgate (University of Chichester) & Jayne Sandys-Renton (University of Sussex) Making the Statue Move: Balancing research within 81 creative writing Anne Lauppe-Dunbar (Swansea University, Wales) 3 eSharp The Lonely Page Two inches of ivory: Short-short prose and gender 92 Laura Tansley (University of Glasgow) The beginnings of solitude 102 David Manderson (University of West Scotland) An extract from the novel The Bridge 110 Karen Stevens (University of Chichester) Poems from the sequence Distance 116 Cath Nichols (Lancaster University) An extract from the novel Lost Bodies 120 David Manderson (University of West Scotland) From the poem Now you're a woman 126 Cherry Smyth (University of Greenwich) Parts One, Two and Three 127 Laura Tansley (University of Glasgow) Marthé 134 Barbara A. -

Simulation (Games)

1 DRAFT of Seth Giddings , Simulation, in Bernard Perron & Mark J. P. Wolf (eds), The Routledge Companion to Video Game Studies, New York: Routledge (forthcoming). Abstract This essay outlines the conventions and pleasures of simulation games as a category, and explores the complicated and contested term simulation. This concept goes to the heart of what computer games and video games are, and the ways in which they articulate ideas, processes, and phenomena between their virtual worlds and the actual world. It has been argued that simulations generate and communicate knowledge and events quite differently from the long-dominant cultural mode of narrative. This raises a thorny question: how, and what, do simulation games simulate? Defining simulation games is a challenge. Whilst most seasoned video game players will have their own idea of what this category of games looks like –and perhaps some favorite examples— these games share no easily identifiable conventions. Classic simulation game series including SimCity (Maxis, 1989) and Civilization (Microprose, 1991) are easily identified by their bird’s-eye — or “God’s eye” — perspective, with the player gazing down on simulated territories and their denizens. But this perspective, and its associated interface devices and gameplay, overlaps and blurs with military strategy games such as the Command & Conquer (Electronic Arts, 1995) and Age of Empires (Microsoft Studios, 1997) series. The category often includes vehicle simulators from A-Train (Maxis, 1985), very similar to SimCity, to Flight -

Favorite Twilight Zone Episodes.Xlsx

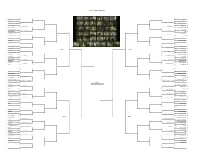

TITLE - VOTING BRACKETS First Round Second Round Sweet Sixteen Elite Eight Final Four Championship Final Four Elite Eight Sweet Sixteen Second Round First Round Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes 1 Time Enough at Last 57 56 Eye of the Beholder 1 Time Enough at Last Eye of the Beholder 32 The Fever 4 5 The Mighty Casey 32 16 A World of Difference 25 19 The Rip Van Winkle Caper 16 I Shot an Arrow into the Air A Most Unusual Camera 17 I Shot an Arrow into the Air 35 41 A Most Unusual Camera 17 8 Third from the Sun 44 37 The Howling Man 8 Third from the Sun The Howling Man 25 A Passage for Trumpet 16 Nervous22 Man in a Four Dollar Room 25 9 Love Live Walter Jameson 34 45 The Invaders 9 Love Live Walter Jameson The Invaders 24 The Purple Testament 25 13 Dust 24 5 The Hitch-Hiker 52 41 The After Hours 5 The Hitch-Hiker The After Hours 28 The Four of Us Are Dying 8 19 Mr. Bevis 28 12 What You Need 40 31 A World of His Own 12 What You Need A World of His Own 21 Escape Clause 19 28 The Lateness of the Hour 21 4 And When the Sky Was Opened 37 48 The Silence 4 And When the Sky Was Opened The Silence 29 The Chaser 21 11 The Mind and the Matter 29 13 A Nice Place to Visit 35 35 The Night of the Meek 13 A Nice Place to Visit The Night of the Meek 20 Perchance to Dream 24 24 The Man in the Bottle 20 Season 1 Season 2 6 Walking Distance 37 43 Nick of Time 6 Walking Distance Nick of Time 27 Mr. -

Constellation Games

CONSTELLATION GAMES A SPACE OPERA SOAP OPERA LEONARD RICHARDSON First serialized in 2011. First trade paperback edition published 2012. Copyright © 2011 by Leonard Richardson All rights reserved. Except as permitted under the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this book may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Please respect the author’s rights; don’t pirate! This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental. For information, address Candlemark & Gleam LLC, 104 Morgan Street, Bennington, VT 05201 [email protected] Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data In Progress ISBN: 978-1-936460-23-6 eISBN: 978-1-936460-24-3 Cover art and design by Chris Sobolowski Book design and composition by Kate Sullivan Proofreaders: Alan Caum Matt Hydeman www.candlemarkandgleam.com For Sumana, again, and all the time. Part One: Hardware Chapter 1: Terrain Deformation Blog post, May 31 What the hell is up with the moon? I am riveted to the news, which is quite the productivity killer because EVERYTHING HAPPENS SO SLOWLY. I have CNN on right now because they have the best satellite footage, and I swear there was just a five-minute discussion about whether or not some- thing is a dust cloud. Yes, it’s a dust cloud! Some fucker is chopping up the moon! You’re going to have a certain amount of dust in that circumstance! But compared to how long you have to wait to see something happen, that five-minute argument goes by as quickly as the time after you hit the snooze button.