Prenuptial Agreements at Work

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HAMAOR Pesach 5775 / April 2015 HAMAOR 3 New Recruits at the Federation

PESACH 5775 / APRIL 2015 3 Parent Families A Halachic perspective 125 Years of Edmonton Federation Cemetery A Chevra Kadisha Seuda to remember Escape from Castelnuovo di Garfagnana An Insider’s A Story of Survival View of the Beis Din Demystifying Dinei Torah hamaor Welcome to a brand new look for HaMaor! Disability, not dependency. I am delighted to introduce When Joel’s parents first learned you to this latest edition. of his cerebral palsy they were sick A feast of articles awaits you. with worry about what his future Within these covers, the President of the Federation 06 might hold. Now, thanks to Jewish informs us of some of the latest developments at the Blind & Disabled, they all enjoy Joel’s organisation. The Rosh Beis Din provides a fascinating independent life in his own mobility examination of a 21st century halachic issue - ‘three parent 18 apartment with 24/7 on site support. babies’. We have an insight into the Seder’s ‘simple son’ and To FinD ouT more abouT how we a feature on the recent Zayin Adar Seuda reflects on some give The giFT oF inDepenDence or To of the Gedolim who are buried at Edmonton cemetery. And make a DonaTion visiT www.jbD.org a restaurant familiar to so many of us looks back on the or call 020 8371 6611 last 30 years. Plus more articles to enjoy after all the preparation for Pesach is over and we can celebrate. My thanks go to all the contributors and especially to Judy Silkoff for her expert input. As ever we welcome your feedback, please feel free to fill in the form on page 43. -

1 Jews, Gentiles, and the Modern Egalitarian Ethos

Jews, Gentiles, and the Modern Egalitarian Ethos: Some Tentative Thoughts David Berger The deep and systemic tension between contemporary egalitarianism and many authoritative Jewish texts about gentiles takes varying forms. Most Orthodox Jews remain untroubled by some aspects of this tension, understanding that Judaism’s affirmation of chosenness and hierarchy can inspire and ennoble without denigrating others. In other instances, affirmations of metaphysical differences between Jews and gentiles can take a form that makes many of us uncomfortable, but we have the legitimate option of regarding them as non-authoritative. Finally and most disturbing, there are positions affirmed by standard halakhic sources from the Talmud to the Shulhan Arukh that apparently stand in stark contrast to values taken for granted in the modern West and taught in other sections of the Torah itself. Let me begin with a few brief observations about the first two categories and proceed to somewhat more extended ruminations about the third. Critics ranging from medieval Christians to Mordecai Kaplan have directed withering fire at the doctrine of the chosenness of Israel. Nonetheless, if we examine an overarching pattern in the earliest chapters of the Torah, we discover, I believe, that this choice emerges in a universalist context. The famous statement in the Mishnah (Sanhedrin 4:5) that Adam was created singly so that no one would be able to say, “My father is greater than yours” underscores the universality of the original divine intent. While we can never know the purpose of creation, one plausible objective in light of the narrative in Genesis is the opportunity to actualize the values of justice and lovingkindness through the behavior of creatures who subordinate themselves to the will 1 of God. -

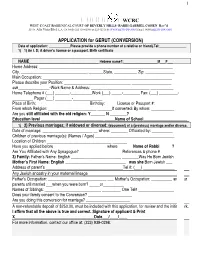

WCRC APPLICATION for GERUT (CONVERSION)

1 WCRC WEST COAST RABBINICAL COURT OF BEVERLY HILLS- RABBI GABRIEL COHEN Rav”d 331 N. Alta Vista Blvd . L.A. CA 90036 323 939-0298 Fax 323 933 3686 WWW.BETH-DIN.ORG Email: INFO@ BETH-DIN.ORG APPLICATION for GERUT (CONVERSION) Date of application: ____________Please provide a phone number of a relative or friend).Tel:_______________ 1) 1) An I. D; A driver’s license or a passport. Birth certificate NAME_______________________ ____________ Hebrew name?:___________________M___F___ Home Address: ________________________________________________________________ City, ________________________________ _______State, ___________ Zip: ______________ Main Occupation: ______________________________________________________________ Please describe your Position: ________________________________ ___________________ ss#_______________-Work Name & Address: ____________________________ ___________ Home Telephone # (___) _______-__________Work (___) _____-________ Fax: (___) _________- __________ Pager (___) ________-______________ Place of Birth: ______________________ ___Birthday:______License or Passport #: ________ From which Religion: _______________________ _______If converted: By whom: ___________ Are you still affiliated with the old religion: Y_______ N ________? Education level ______________________________ _____Name of School_____________________ 1) 2) Previous marriages; if widowed or divorced: (document) of a (previous) marriage and/or divorce. Date of marriage: ________________________ __ where: ________ Officiated by: __________ Children -

Britain's Orthodox Jews in Organ Donor Card Row

UK Britain's Orthodox Jews in organ donor card row By Jerome Taylor, Religious Affairs Correspondent Monday, 24 January 2011 Reuters Chief Rabbi Jonathan Sacks has ruled that national organ donor cards are not permissable, and has advised followers not to carry them Britain’s Orthodox Jews have been plunged into the centre of an angry debate over medical ethics after the Chief Rabbi ruled that Jews should not carry organ donor cards in their current form. London’s Beth Din, which is headed by Lord Jonathan Sacks and is one of Britain’s most influential Orthodox Jewish courts, caused consternation among medical professionals earlier this month when it ruled that national organ donor cards were not permissible under halakha (Jewish law). The decision has now sparked anger from within the Orthodox Jewish community with one prominent Jewish rabbi accusing the London Beth Din of “sentencing people to death”. Judaism encourages selfless acts and almost all rabbinical authorities approve of consensual live organ donorship, such as donating a kidney. But there are disagreements among Orthodox leaders over when post- mortem donation is permissible. Liberal, Reform and many Orthodox schools of Judaism, including Israel’s chief rabbinate, allow organs to be taken from a person when they are brain dead – a condition most doctors consider to determine the point of death. But some Orthodox schools, including London’s Beth Din, have ruled that a person is only dead when their heart and lungs have stopped (cardio-respiratory failure) and forbids the taking of organs from brain dead donors. As the current donor scheme in Britain makes no allowances for such religious preferences, Rabbi Sacks and his fellow judges have advised their followers not to carry cards until changes are made. -

Report of the Regulatory Board of Brit Milah in South Arica

REPORT OF THE REGULATORY BOARD OF BRIT MILAH IN SOUTH AFRICA (“THE REGULATORY BOARD”) 2016 - 2018 1 Background The Regulatory Board of Brit Milah in South Africa was established by Chief Rabbi Dr Warren Goldstein in 2016. The Regulatory Board acts in terms of the delegated authority of the Chief Rabbi and Head of the Beth Din (Court of Jewish Law), Rabbi Moshe Kurtstag. This report covers the activities of the Regulatory Board since inception in April 2016. The number of Britot reported are for the calendar years 2016 and 2017. The Regulatory Board is responsible for: 1.1 Ensuring the very highest standards of care and safety for all infants undergoing a Brit Milah and ensuring that this sacred and holy procedure is conducted according to strict Halachic principles (Jewish law); 1.2 The development of standardised guidelines, policies and procedures to ensure that the highest standards of safety in the performance of Brit Milah are maintained in South Africa; 1.3 Ensuring the appropriate registration, training, accreditation and continuing education of practising Mohalim (plural for Mohel, a person who is trained to perform a circumcision according to Jewish law); 1.4 Maintaining all records of Brit Milahs performed in South Africa; and 1.4 Fully investigating any concerns or complaints raised regarding Brit 1 Milah with the authority to recommend and to institute the appropriate remedial action. The current members of the Regulatory Board are: Dr Richard Friedland (Chairperson). Rabbi Dr Pinhas Zekry (Expert Mohel). Rabbi Anton Klein (Beth Din Representative). Dr Reuven Jacks (Medical Officer). Dr Joseph Spitzer (Mohel and Medical Adviser). -

TORAH TO-GO® Established by Rabbi Hyman and Ann Arbesfeld June 2017 • Shavuot 5777 a Special Edition Celebrating President Richard M

Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary Yeshiva University Center for the Jewish Future THE BENJAMIN AND ROSE BERGER TORAH TO-GO® Established by Rabbi Hyman and Ann Arbesfeld June 2017 • Shavuot 5777 A Special Edition Celebrating President Richard M. Joel WITH SHAVUOT TRIBUTES FROM Rabbi Dr. Kenneth Brander • Rabbi Dr. Hillel Davis • Rabbi Dr. Avery Joel • Dr. Penny Joel Rabbi Dr. Josh Joseph • Rabbi Menachem Penner • Rabbi Dr. Jacob J. Schacter • Rabbi Ezra Schwartz Special Symposium: Perspectives on Conversion Rabbi Eli Belizon • Joshua Blau • Mrs. Leah Nagarpowers • Rabbi Yona Reiss Rabbi Zvi Romm • Mrs. Shoshana Schechter • Rabbi Michoel Zylberman 1 Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary • The Benjamin and Rose Berger CJF Torah To-Go Series • Shavuot 5777 We thank the following synagogues which have pledged to be Pillars of the Torah To-Go® project Beth David Synagogue Green Road Synagogue Young Israel of West Hartford, CT Beachwood, OH Century City Los Angeles, CA Beth Jacob Congregation The Jewish Center Beverly Hills, CA New York, NY Young Israel of Bnai Israel – Ohev Zedek Young Israel Beth El of New Hyde Park New Hyde Park, NY Philadelphia, PA Borough Park Koenig Family Foundation Young Israel of Congregation Brooklyn, NY Ahavas Achim Toco Hills Atlanta, GA Highland Park, NJ Young Israel of Lawrence-Cedarhurst Young Israel of Congregation Cedarhurst, NY Shaarei Tefillah West Hartford West Hartford, CT Newton Centre, MA Richard M. Joel, President and Bravmann Family University Professor, Yeshiva University Rabbi Dr. Kenneth -

Presenter Profiles

PRESENTER PROFILES RABBI KENNETH BRANDER Rabbi Kenneth Brander is Vice President for University and Community Life at Yeshiva University. He served as the inaugural David Mitzner Dean of Yeshiva University Center for the Jewish Future. Prior to his work at Yeshiva University, Rabbi Brander served for 14 years as the Senior Rabbi of the Boca Raton Synagogue. He oversaw its explosive growth from 60 families to over 600 families. While Senior Rabbi of the Boca Raton Synagogue (BRS), he became the founding dean of The Weinbaum Yeshiva High School, founding dean of the Boca Raton Judaic Fellows Program – Community Kollel and founder and posek of the Boca Raton Community Mikvah. He helped to develop the Hahn Judaic Campus on which all these institutions reside and as co-chair of Kashrut organization of the Orthodox Rabbinical Board of Broward & Palm Beach Counties (ORB). Rabbi Brander also served for five years as a Member of the Executive Board of the South Palm Beach County Jewish Federation, as a Board member of Jewish Family Services of South Palm Beach County, and actively worked with other lay leaders in the development of the Hillel Day School. Rabbi Brander is a 1984 alumnus of Yeshiva College and received his ordination from the Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary in 1986. During that time he served as a student assistant to the esteemed Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik. He also received an additional ordination from Rav Menachem Burstein the founder and dean of Machon Puah and from the Chief Rabbi, Mordechai Eliyahu, in the field of Jewish Law and Bioethics with a focus on reproductive technology, He is currently a PhD candidate (ABD) in general philosophy at Florida Atlantic University (FAU). -

The Contemporary Jewish Legal Treatment of Depressive Disorders in Conflict with Halakha

t HaRofei LeShvurei Leiv: The Contemporary Jewish Legal Treatment of Depressive Disorders in Conflict with Halakha Senior Honors Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the School of Arts and Sciences Brandeis University Undergraduate Program in Near Eastern and Judaic Studies Prof. Reuven Kimelman, Advisor Prof. Zvi Zohar, Advisor In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts by Ezra Cohen December 2018 Accepted with Highest Honors Copyright by Ezra Cohen Committee Members Name: Prof. Reuven Kimelman Signature: ______________________ Name: Prof. Lynn Kaye Signature: ______________________ Name: Prof. Zvi Zohar Signature: ______________________ Table of Contents A Brief Word & Acknowledgments……………………………………………………………... iii Chapter I: Setting the Stage………………………………………………………………………. 1 a. Why This Thesis is Important Right Now………………………………………... 1 b. Defining Key Terms……………………………………………………………… 4 i. Defining Depression……………………………………………………… 5 ii. Defining Halakha…………………………………………………………. 9 c. A Short History of Depression in Halakhic Literature …………………………. 12 Chapter II: The Contemporary Legal Treatment of Depressive Disorders in Conflict with Halakha…………………………………………………………………………………………. 19 d. Depression & Music Therapy…………………………………………………… 19 e. Depression & Shabbat/Holidays………………………………………………… 28 f. Depression & Abortion…………………………………………………………. 38 g. Depression & Contraception……………………………………………………. 47 h. Depression & Romantic Relationships…………………………………………. 56 i. Depression & Prayer……………………………………………………………. 70 j. Depression & -

Israel 2019 International Religious Freedom Report

ISRAEL 2019 INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM REPORT Executive Summary This section covers Israel, including Jerusalem. In December 2017, the United States recognized Jerusalem as the capital of Israel. It is the position of the United States that the specific boundaries of Israeli sovereignty in Jerusalem are subject to final status negotiations between the parties. The Palestinian Authority (PA) exercises no authority over Jerusalem. In March 2019, the United States recognized Israeli sovereignty over the Golan Heights. A report on the West Bank and Gaza, including areas subject to the jurisdiction of the PA, is appended at the end of this report. The country’s laws and Supreme Court rulings protect the freedoms of conscience, faith, religion, and worship, regardless of an individual’s religious affiliation, and the 1992 “Basic Law: Human Dignity and Liberty” protects additional individual rights. In 2018, the Knesset passed the “Basic Law: Israel – The Nation State of the Jewish People.” According to the government, that “law determines, among other things, that the Land of Israel is the historical homeland of the Jewish people; the State of Israel is the nation state of the Jewish People, in which it realizes its natural, cultural, religious and historical right to self-determination; and exercising the right to national self-determination in the State of Israel is unique to the Jewish People.” The government continued to allow controlled access to religious sites, including the Temple Mount/Haram al-Sharif (the site containing the foundation of the first and second Jewish temple and the Dome of the Rock and al-Aqsa Mosque). -

Sukkos, 5781 Dear Talmidim, the Recent Uptick in Covid-19 Prompts

1 Sukkos, 5781 Dear Talmidim, The recent uptick in Covid-19 prompts this letter. The Torah requires that we avoid dangerous activity. The protection afforded to Mitzvah performance does not apply when danger is prevalent (Pesachim 8b). In all gatherings, masks covering everyone's mouth and nose must be worn. In addition, appropriate social distance between attendees (except for members of the same household) must be maintained. Hands must be washed with soap and water or with proper hand sanitizer. On Shabbos and Yom Tov liquid soap or sanitizer may and must be used. On Simchas Torah, the usual hakafos and dancing are prohibited. At the discretion of every local rav, hakafos may be limited or eliminated. Any dancing must be done while wearing masks and socially distanced. Upon advice from medical experts, we recommend that the sefer Torah not be passed from one person to another. Preferably, one person should circle the bima 7 times. After each hakafa the tzibur should join in an appropriate nigun and "dance" in place. The practice of everyone getting an aliya is a minhag, not a din, and may be adjusted or eliminated at the discretion of the local rav (see links here and here for similar horaos}. Similarly, at weddings the usual dancing is prohibited. Any dancing must be done while wearing masks and socially distanced. Chasanim and their families are urged to limit the size of weddings and to insist upon and enforce masking and appropriate distancing by all their guests. Adherence to all the above is required by the halacha which demands great caution to protect life and good health. -

The Elijah Interfaith Academy First Meeting of Board of World Religious Leaders Seville, Dec

The Elijah Interfaith Academy First Meeting of Board of World Religious Leaders Seville, Dec. 14-17, 2003 Report Prepared by Alon Goshen-Gottstein and Barry Levy Introduction The Elijah Interfaith Academy held the first meeting of its board of world religious leaders in Seville, Spain, Dec. 14-17, 2003. The event was hosted by the Sevilla Nodo Foundation, which expresses its commitment, based on the heritage of Al Andalus, to provide an open space for dialogue, mutual respect and enriching encounters. The purpose of the meeting was to form a board of world religious leaders that would direct, endorse and be affiliated with the work of the Elijah Interfaith Academy. The meeting served as an opportunity to present a pilot project of the Interfaith Academy, addressing issues of xenophobia from the perspectives of Judaism, Christianity, Islam, Hinduism and Buddhism. Advance preparation of the event by the Elijah Think-tank facilitated high-level discussion of the topic. The model project stimulated assembled leaders to plan the activities of the Interfaith Academy in coming years. The meeting was hugely successful in forging a common vision between scholars and religious leaders, in developing a sense of ownership and partnership of the Academy by assembled religious leaders, in forming a cohesive group of religious leaders and strengthening personal bonds between them and in having public impact. In addition, alongside the board of religious leaders an administrative board was formed, with the purpose of advancing and implementing the vision of the Interfaith Academy. The following report is divided into seven parts. A. Goals B. Review of schedule and activities C. -

Assorted Matters,The Valmadonna Broadside

Assorted Matters Assorted Matters Marc B. Shapiro My next post will take some time to prepare, but there are some other matters that I want to bring to readers’ attention, in particular a few books that I recently received. Due to space considerations, I couldn’t include these in my last post. 1. For those interested in the history of Lithuanian yeshivot, the last few years have been very fruitful. In 2014 Ben-Tsiyon Klibansky’s Ke-Tzur Halamish appeared. This book is a study of the yeshivot from World War I until the destruction of European Jewry. 2015 saw the appearance of Geoffrey D. Claussen’s Sharing the Burden: Rabbi Simhah Zissel Ziv and the Path of Mussar.[1]In January 2016 Shlomo Tikoshinski’s long- awaited book appeared. Its title isLamdanut, Musar ve- Elitizm: Yeshivat Slobodka me-Lita le-Eretz Yisrael. The book can be purchased here. Eliezer Brodt is also selling the book and a portion of each sale will go to support the efforts of the Seforim Blog, so I also encourage purchasing from him. This outstanding book is full of new information, and Tikoshinski had access to a variety of private archives and letters that help bring to life a world now lost. Lamdanut, Musar ve-Elitizm is also a crucial source in understanding the development of religious life in Eretz Yisrael in the two decades before the creation of the State. When you read about the Slobodka students, and later the students of Chevron, it is impossible not to see how very different the student culture was then from what is found today in haredi yeshivot, including the contemporary Yeshivat Chevron.