Indigenous Knowledge Systems and the Question of Openness

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

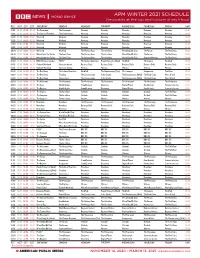

APM WINTER 2021 SCHEDULE Newscasts at the Top and Bottom of Each Hour

APM WINTER 2021 SCHEDULE Newscasts at the top and bottom of each hour PST MST CST EST SATURDAY SUNDAY MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY GMT 21:00 22:00 23:00 00:00 The Newsroom The Newsroom Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday 05:00 21:30 22:30 23:30 00:30 The Cultural Frontline The Conversation Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday 05:30 22:00 23:00 00:00 01:00 Weekend Weekend Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday 06:00 22:30 23:30 00:30 01:30 Weekend Weekend Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday 06:30 23:00 00:00 01:00 02:00 Weekend Weekend Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday 07:00 23:30 00:30 01:30 02:30 Weekend Weekend Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday 07:30 00:00 01:00 02:00 03:00 Weekend Weekend The History Hour The Arts Hour W’end Doc/Bk Club The Forum The Real Story 08:00 00:30 01:30 02:30 03:30 When Katty Met Carlos The Food Chain The History Hour The Arts Hour W’end Doc/Bk Club The Forum The Real Story 08:30 00:50 01:50 02:50 03:50 When Katty Met Carlos The Food Chain The History Hour The Arts Hour W’end Doc/Bk Club Sporting Witness The Real Story 08:50 01:00 02:00 03:00 04:00 BBC OS Conversations FOOC* The Climate Question People Fixing the World HardTalk The Inquiry HardTalk 09:00 01:30 02:30 03:30 04:30 Outlook Weekend Science in Action Business Daily Business Daily Business Daily Business Daily Business Daily 09:30 01:50 02:50 03:50 04:50 Outlook Weekend Science in Action Witness Witness Witness Witness Witness 09:50 02:00 03:00 04:00 05:00 The Real Story The Cultural Frontline HardTalk The Documentary -

Digital Planet 2017 How Competitiveness and Trust in Digital Economies Vary Across the World

DIGITAL PLANET 2017 HOW COMPETITIVENESS AND TRUST IN DIGITAL ECONOMIES VARY ACROSS THE WORLD Bhaskar Chakravorti and Ravi Shankar Chaturvedi The Fletcher School, Tufts University July 2017 WELCOME SPONSOR DATA PARTNERS OTHER DATA SOURCES CIGI-IPSOS GSMA Wikimedia Edelman ILO World Bank Euromonitor ITU World Economic Forum Freedom House Numbeo World Values Survey Google Web Index DIGITAL PLANET 2017 HOW COMPETITIVENESS AND TRUST IN DIGITAL ECONOMIES VARY ACROSS THE WORLD 2 WELCOME AUTHORS DR. BHASKAR CHAKRAVORTI Principal Investigator The Senior Associate Dean of International Business and Finance at The Fletcher School, Dr. Bhaskar Chakravorti is also the founding Executive Director of Fletcher’s Institute for Business in the Global Context (IBGC) and a Professor of Practice in International Business. Dean Chakravorti has extensive experience in academia, strategy consulting, and high-tech R&D. Prior to Fletcher, Dean Chakravorti was a Partner at McKinsey & Company and a Distinguished Scholar at MIT’s Legatum Center for Development and Entrepreneurship. He has also served on the faculty of the Harvard Business School and the Harvard University Center for the Environment. He serves on the World Economic Forum’s Global Future Council on Innovation and Entrepreneurship and the Advisory Board for the UNDP’s International Center for the Private Sector in Development, is a Non-Resident Senior Fellow at the Brookings Institution India and the Senior Advisor for Digital Inclusion at The Mastercard Center for Inclusive Growth. Chakravorti’s book, The Slow Pace of Fast Change: Bringing Innovations to Market in a Connected World, Harvard Business School Press; 2003, was rated one of the best business books of the year by multiple publications and was an Amazon.com best seller on innovation. -

Morrie Gelman Papers, Ca

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8959p15 No online items Morrie Gelman papers, ca. 1970s-ca. 1996 Finding aid prepared by Jennie Myers, Sarah Sherman, and Norma Vega with assistance from Julie Graham, 2005-2006; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé. UCLA Library Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA, 90095-1575 (310) 825-4988 [email protected] ©2016 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Morrie Gelman papers, ca. PASC 292 1 1970s-ca. 1996 Title: Morrie Gelman papers Collection number: PASC 292 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Language of Material: English Physical Description: 80.0 linear ft.(173 boxes and 2 flat boxes ) Date (inclusive): ca. 1970s-ca. 1996 Abstract: Morrie Gelman worked as a reporter and editor for over 40 years for companies including the Brooklyn Eagle, New York Post, Newsday, Broadcasting (now Broadcasting & Cable) magazine, Madison Avenue, Advertising Age, Electronic Media (now TV Week), and Daily Variety. The collection consists of writings, research files, and promotional and publicity material related to Gelman's career. Physical location: Stored off-site at SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact UCLA Library Special Collections for paging information. Creator: Gelman, Morrie Restrictions on Access Open for research. STORED OFF-SITE AT SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact UCLA Library Special Collections for paging information. Restrictions on Use and Reproduction Property rights to the physical object belong to the UC Regents. Literary rights, including copyright, are retained by the creators and their heirs. -

World Service Listings for 26 December 2020 – 1 January 2021 Page 1 of 15 SATURDAY 26 DECEMBER 2020 Mosul After Islamic State Image: Bodhi

World Service Listings for 26 December 2020 – 1 January 2021 Page 1 of 15 SATURDAY 26 DECEMBER 2020 Mosul after Islamic State Image: Bodhi. Credit: @mensweardog Iraqis recently celebrated Victory Day, which marks the day in SAT 00:00 BBC News (w172x5p70g4dzz9) December 2017 when the last remnants of so-called Islamic The latest five minute news bulletin from BBC World Service. State were finally driven from the country. The toughest part of SAT 06:00 BBC News (w172x5p70g4fqg2) that campaign was the battle to retake Mosul, captured by IS in The latest five minute news bulletin from BBC World Service. 2014. Two BBC journalists who reported on the fighting - SAT 00:06 Trending (w3ct1d1z) Nafiseh Kohnavard of BBC Persian, and BBC Arabic's Basheer Votes, viruses, victims: 2020 in disinformation Al-Zaidi - share memories, and tell us what Mosul is like now. SAT 06:06 Weekend (w172x7d6wthd2qs) Explosion in Nashville From the global pandemic to the US election, the extraordinary In praise of borsch events of 2020 have both fuelled, and been shaped by, the Roman Lebed of BBC Ukrainian gives us his ode to borsch, the A camper van in Nashville, Tennessee has exploded, injuring online spread of falsehoods, propaganda and bizarre conspiracy beetroot soup eaten all over Ukraine and Russia. But who made three people. The blast also knocked out communications theories. it first? Roman tells us about the battle over its origins, and systems across the state. The camper van broadcast a warning shares memories of his great-grandmother's recipe, as well as message to leave the area, before the blast. -

Simon Redfern the Media Fellowship

Simon Redfern Professor of Mineral Physics, University of Cambridge BBC Radio and Science & Environment News Online The Media Fellowship One of the most nerve wracking moments was in my very first week, when I was working with the BBC Science Radio folk on a couple of productions, one going out on the BBC World Service and one on UK domestic BBC Radio 4. The latter was the very last edition of “Material World”. It went out live and being involved in live radio, even as a minor researcher for only part of the programme, was fascinating. The topic of “my” bit of the show was communicating scientific uncertainty and my contribution amounted to telephoning potential guest interviewees and getting them to agree to sitting in front of a microphone. When faced with attempting to write a script for how I believed the discussion would proceed, I had to rely on the answers that they had given during my phone conversations with them earlier in the week. I waited on tenterhooks during their part of the programme, terrified that the interviewees would go wildly off message and sink the whole discussion. But they did an excellent job of discussing a difficult concept. The presenter, Gareth Mitchell, was fantastic, and it was a highlight watching him guide the show so professionally and calmly. Working with the Science and Environment page of BBC News Online was also very rewarding. Seeing your words transformed from hastily scribbled reports of the latest research papers, into slick pieces on the BBC News Site was great fun every time. -

4 December 2020 Page 1 of 17 SATURDAY 28 NOVEMBER 2020 Already Set up and Ready for Business

World Service Listings for 28 November – 4 December 2020 Page 1 of 17 SATURDAY 28 NOVEMBER 2020 already set up and ready for business. BBC Thai's Chaiyot SAT 06:06 Weekend (w172x7d5fr78h9f) Yongcharoenchai set out to crack the mystery of the self-styled Iranian nuclear scientist killed SAT 00:00 BBC News (w172x5p5kcw9djy) "CIA" food hawkers. The latest five minute news bulletin from BBC World Service. Iran has urged the United Nations to condemn the assassination ‘They messed with the wrong generation’ of its top nuclear scientist, Mohsen Fakhrizadeh, and it's Peru has been in the headlines for having three presidents in a pointed the finger at Israel. We explore how the incoming SAT 00:06 The Real Story (w3cszcnx) week. It’s a story of corruption allegations, impeachment and Biden administration's relationship with its traditional ally will Covid vaccines: An opportunity for science? mass protests, with young people saying their generation has shape regional tensions. had enough of the broken system which their parents put up The rapid development of coronavirus vaccines has heightened with. Ana Maria Roura has been making sense of events for Also on the programme: The number of confirmed coronavirus the hope for a world free of Covid-19. Governments have BBC Mundo. cases in the United States has passed thirteen million, with the ordered millions of doses, health care systems are prioritising pandemic still surging from coast to coast; And a new recipients, and businesses are drawing up post-pandemic plans. Lahore's toxic smog documentary explores Frank Zappa the man, his music, and But despite these positive signs, many people still feel a sense It's the time of year when many Pakistani rice farmers set fire politics. -

World Service Listings for 8 – 14 May 2021 Page 1 of 16

World Service Listings for 8 – 14 May 2021 Page 1 of 16 SATURDAY 08 MAY 2021 A short walk in the Russian woods Producer: Ant Adeane Another chance to hear Oleg Boldyrev of BBC Russian SAT 01:00 BBC News (w172xzjhw8w2cdg) enjoying last year's Spring lockdown in the company of fallen The latest five minute news bulletin from BBC World Service. trees, fungi, and beaver dams. SAT 05:50 More or Less (w3ct2djx) Finding Mexico City’s real death toll Image: 'Open Jirga' presenter Shazia Haya with all female SAT 01:06 Business Matters (w172xvq9r0rzqq5) audience in Kandahar Mexico City’s official Covid 19 death toll did not seem to President Biden insists US is 'on the right track' despite lower Credit: BBC Media Action reflect the full extent of the crisis that hit the country in the job numbers spring of 2020 - this is according to Laurianne Despeghel and Mario Romero. These two ordinary citizens used publicly The US economy added 266,000 jobs in April, far fewer than SAT 03:50 Witness History (w3ct1wyg) available data to show that excess deaths during the crisis - economists had predicted. President Biden has said his Surviving Guantanamo that’s the total number of extra deaths compared to previous economic plan is working despite the disappointing numbers. years - was four times higher than the confirmed Covid 19 We get analysis from Diane Swonk, chief economist at After 9/11 the USA began a programme of 'extraordinary deaths. accountancy firm Grant Thornton in Chicago. rendition', moving prisoners between countries without legal Also in the programme, Kai Ryssdal from our US partners representation. -

World Service Listings for 2 – 8 January 2021 Page 1 of 15 SATURDAY 02 JANUARY 2021 Arabic’S Ahmed Rouaba, Who’S from Algeria, Explains Why This with Their Heritage

World Service Listings for 2 – 8 January 2021 Page 1 of 15 SATURDAY 02 JANUARY 2021 Arabic’s Ahmed Rouaba, who’s from Algeria, explains why this with their heritage. cannon still means so much today. SAT 00:00 BBC News (w172x5p7cqg64l4) To comment on these stories and others we are joined on the The latest five minute news bulletin from BBC World Service. Remedies for the morning after programme by Emma Bullimore, a British journalist and Before coronavirus concerns in many countries, this was the broadcaster specialising in the arts, television and entertainment time of year for parties. But what’s the advice for the morning and Justin Quirk, a British writer, journalist and culture critic. SAT 00:06 BBC Correspondents' Look Ahead (w3ct1cyx) after, if you partied a little too hard? We consult Oleg Boldyrev BBC correspondents' look ahead of BBC Russian, Suping of BBC Chinese, Brazilian Fernando (Photo : Indian health workers prepare for mass vaccination Duarte and Sharon Machira of BBC Nairobi for their local drive; Credit: EPA/RAJAT GUPTA) There were times in 2020 when the world felt like an out of hangover cures. control carousel and we could all have been forgiven for just wanting to get off and to wait for normality to return. Image: Congolese house at the shoreline of Congo river SAT 07:00 BBC News (w172x5p7cqg6zt1) Credit: guenterguni/Getty Images The latest five minute news bulletin from BBC World Service. But will 2021 be any less dramatic? Joe Biden will be inaugurated in January but will Donald Trump have left the White House -

Anti-Wi-Fi Paint Offers Security

Low graphics Help Search Explore the BBC ONE-MINUTE WORLD NEWS Page last updated at 11:59 GMT, Wednesday, 30 September 2009 12:59 UK News Front Page E-mail this to a friend Printable version Anti-wi-fi paint offers security Africa DIGITAL PLANET SEE ALSO Americas By Dave Lee Teacher switches off class wi-fi Asia-Pacific BBC World Service 25 Sep 09 | Northern Ireland Europe Researchers say they have 'Next generation' wi-fi approved Middle East created a special kind of paint 14 Sep 09 | Technology which can block out wireless South Asia NY cafes crack down on free wi-fi signals. 14 Aug 09 | Technology UK Business It means security-conscious RELATED INTERNET LINKS Health wireless users could block their Shin-ichi Ohkoshi Science & Environment neighbours from being able to The BBC is not responsible for the content of external access their home network - internet sites Technology without having to set up Entertainment encryption. TOP TECHNOLOGY STORIES Also in the news ----------------- The paint contains an aluminium- Microsoft bets on Windows success Video and Audio iron oxide which resonates at the EU warns Oracle over Sun takeover ----------------- same frequency as wi-fi - or other Government opens data to public Programmes radio waves - meaning the | News feeds Have Your Say airborne data is absorbed and In Pictures blocked. With a quick lick of paint, your wi-fi Country Profiles connection could be secured By coating an entire room, signals MOST POPULAR STORIES NOW Special Reports can't get in and, crucially, can't get out. SHARED READ WATCHED/LISTENED Related BBC sites Developed at the University of Tokyo, the paint could cost as little as Sport Leaping wolf snatches photo prize £10 per kilogram, researchers say. -

Info7 2017-2 S-48-51

48 AUS WISSENSCHAFT UND FORSCHUNG info7 2|2017 Von »Old Media« zum interaktiven Radio? Julia Lorke Man startet gemeinsam in den Tag, sobald der Ra dio- Charakter zu bewahren. Es scheint also häufig so, als wecker klingelt, man liest gemeinsam Zeitung und würde man als Hörer tatsächlich Zeit mit den Mode- fährt gemeinsam zur Arbeit. Spätestens zur Rush ra toren der Radiosendung verbringen. Aller dings Hour trifft man sich im Auto wieder, kocht gemein- scheint die Kommunikation hier eher unidirektional sam, geht zu Bett und ist am nächsten Morgen, wenn zu sein, und das ist eine eher wenig attraktive Kom- der Wecker klingelt, wieder vereint. Die Rede ist hier munikationsform in zwischenmenschlichen Bezieh- nicht von zwischenmenschlichen Beziehun gen son- un gen. Dank des technologischen Fort schritts sind dern es geht um die Beziehung zwischen dem Radio jedoch auch im Bereich von Radio und seinem Pub- und seinen Hörern. Radio wird nicht umsonst als likum vielfältige Kommu nika tions for men möglich. Dr. Julia Lorke Imperial College „the intimate medium“ bezeichnet, denn Radio be- Nach Tiziano Bonini lässt sich die historische Ent- London gleitet uns in Alltagssituationen, sogar solche, die wir wicklung der Beziehung des Mediums Radio zu sei- MSc Science Communication sonst nur mit unserem Partner oder unserer Familie nem Publikum in vier Phasen einteilen (siehe Tabelle 1). South Kensington verbringen. Aber selbst wenn wir ganz alleine Radio Diese Phasen zeigen deutlich, wie technologi- Campus - oder natürlich Podcasts – hören werden wir meist sche Entwicklungen dazu beigetragen haben, dass London SW7 2AZ +49 2821 8067 39730 direkt angesprochen von den Moderatoren. -

September 2010

BEN- GURION UNIVERSITY OF THE NEGEV FACULTY OF HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF MIDDLE EAST SCIENCES Portrayals of Neda Agha-Soltan's Death: State-Funded English-Language News Networks and the Post-2009 Iranian Election Unrest THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS NEAL UNGERLEIDER UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF DR. HAGGAI RAM UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF DR. TAL SAMUEL-AZRAN SEPTEMBER 2010 1 BEN- GURION UNIVERSITY OF THE NEGEV FACULTY OF HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF MIDDLE EASTERN SCIENCES Portrayals of Neda Agha-Soltan's Death: State-Funded English-Language News Networks and the Post-2009 Iranian Election Unrest THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS NEAL UNGERLEIDER UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF DR. HAGGAI RAM UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF DR. TAL SAMUEL-AZRAN Signature of student: ________________ Date: _________ Signature of supervisor: ________________ Date: _________ Signature of supervisor: ________________ Date: _________ Signature of chairperson of the committee for graduate studies: ________________ Date: _________ 2 Abstract: This thesis examines international media coverage of Neda Agha-Soltan, a 26-year-old Iranian woman who died of a gunshot wound in Tehran during the 2009 post-election demonstrations. Agha-Soltan's death was captured by at least two camerapersons. The resulting footage appeared on television news worldwide, with Agha-Soltan's death becoming one of the most readily identifiable images of the demonstrations in Iran. International media in Iran relied strongly on user-generated content created by bystanders in Tehran. For international news organizations who found their employees expelled from Iran, use of bystander-generated footage became a convenient method of reporting on a major world event. -

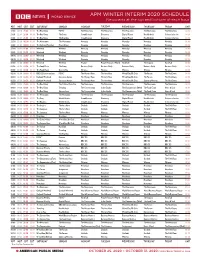

2020 BBC Fall Schedule

APM WINTER INTERIM 2020 SCHEDULE Newscasts at the top and bottom of each hour PDT MDT CDT EDT SATURDAY SUNDAY MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY GMT 21:00 22:00 23:00 00:00 The Real Story FOOC* The Newsroom The Newsroom The Newsroom The Newsroom The Newsroom 04:00 21:30 22:30 23:30 00:30 The Real Story The Story CrowdScience Discovery Digital Planet Healthcheck Science in Action 04:30 21:50 22:50 23:50 00:50 The Real Story The Big Idea CrowdScience Discovery Digital Planet Healthcheck Science in Action 04:50 22:00 23:00 00:00 01:00 The Newsroom The Newsroom Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday 05:00 22:30 23:30 00:30 01:30 The Cultural Frontline Heart & Soul Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday 05:30 23:00 00:00 01:00 02:00 Weekend Weekend Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday 06:00 23:30 00:30 01:30 02:30 Weekend Weekend Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday 06:30 00:00 01:00 02:00 03:00 Weekend Weekend Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday 07:00 00:30 01:30 02:30 03:30 Weekend Weekend Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday 07:30 01:00 02:00 03:00 04:00 Weekend Weekend Feature People Fixing the World HardTalk The Inquiry HardTalk 08:00 01:30 02:30 03:30 04:30 The Food Chain The Story Business Daily Business Daily Business Daily Business Daily Business Daily 08:30 01:50 02:50 03:50 04:50 The Food Chain Over to You Witness Witness Witness Witness Witness 08:50 02:00 03:00 04:00 05:00 BBC OS Conversations FOOC* The History Hour The Arts Hour W’end Doc/Bk Club The Forum The Real Story 09:00 02:30 03:30 04:30 05:30 Outlook