Marine Bird Important Bird Areas in Southeastern Newfoundland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beaufort Seas West To

71° 162° 160° 158° 72° U LEGEND 12N 42W Ch u $ North Slope Planning Area ckchi Sea Conservation System Unit (Offset for display) Pingasagruk (abandoned) WAINWRIGHT Atanik (Abandoned) Naval Arctic Research Laboratory USGS 250k Quad Boundaries U Point Barrow I c U Point Belcher 24N Township Boundaries y 72° Akeonik (Ruins) Icy Cape U 17W C 12N Browerville a Trans-Alaska Pipeline p 39W 22N Solivik Island e Akvat !. P Ikpilgok 20W Barrow Secondary Roads (unpaved) a Asiniak!. Point s MEADE RIVER s !. !. Plover Point !. Wainwright Point Franklin !. Brant Point !. Will Rogers and Wiley Post Memorial Whales1 U Point Collie Tolageak (Abandoned) 9N Point Marsh Emaiksoun Lake Kilmantavi (Abandoned) !. Kugrua BayEluksingiak Point Seahorse Islands Bowhead Whale, Major Adult Area (June-September) 42W Kasegaluk Lagoon West Twin TekegakrokLake Point ak Pass Sigeakruk Point uitk A Mitliktavik (Abandoned) Peard Bay l U Ikroavik Lake E Tapkaluk Islands k Wainwright Inlet o P U Bowhead Whale, Major Adult Area (May) l 12N k U i i e a n U re Avak Inlet Avak Point k 36W g C 16N 22N a o Karmuk Point Tutolivik n U Elson Lagoon t r !. u a White (Beluga) Whale, Major Adult Area (September) !. a !. 14N m 29W 17W t r 17N u W Nivat Point o g P 32W Av k a a Nokotlek Point !. 26W Nulavik l A s P v a a s Nalimiut Point k a k White (Beluga) Whale, Major Adult Area (May-September) MEADE RIVER p R s Pingorarok Hill BARROW U a Scott Point i s r Akunik Pass Kugachiak Creek v ve e i !. -

International Black-Legged Kittiwake Conservation Strategy and Action Plan Acknowledgements Table of Contents

ARCTIC COUNCIL Circumpolar Seabird Expert Group July 2020 International Black-legged Kittiwake Conservation Strategy and Action Plan Acknowledgements Table of Contents Executive Summary ..............................................................................................................................................4 CAFF Designated Agencies: Chapter 1: Introduction .......................................................................................................................................5 • Norwegian Environment Agency, Trondheim, Norway Chapter 2: Ecology of the kittiwake ....................................................................................................................6 • Environment Canada, Ottawa, Canada Species information ...............................................................................................................................................................................................6 • Faroese Museum of Natural History, Tórshavn, Faroe Islands (Kingdom of Denmark) Habitat requirements ............................................................................................................................................................................................6 • Finnish Ministry of the Environment, Helsinki, Finland Life cycle and reproduction ................................................................................................................................................................................7 • Icelandic Institute of Natural -

Niiwalarra Islands and Lesueur Island

Niiwalarra Islands (Sir Graham Moore Islands) National Park and Lesueur Island Nature Reserve Joint management plan 2019 Management plan 93 Conservation and Parks Commission Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions Parks and Wildlife Service 17 Dick Perry Avenue Technology Park, Western Precinct KENSINGTON WA 6151 Phone (08) 9219 9000 Fax (08) 9334 0498 dbca.wa.gov.au © State of Western Australia 2019 December 2019 ISBN 978-1-925978-03-2 (print) ISBN 978-1-921703-94-2 (online) WARNING: This plan may show photographs of, and refer to quotations from people who have passed away. This work is copyright. All traditional and cultural knowledge in this joint management plan is the cultural and intellectual property of Kwini Traditional Owners and is published with the consent of Balanggarra Aboriginal Corporation on their behalf. Written consent from Balanggarra Aboriginal Corporation must be obtained for use or reproduction of any such materials. Any unauthorised dealing may be in breach of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). All other non-traditional and cultural content in this joint management plan may be downloaded, displayed, printed and reproduced in unaltered form for personal use, non-commercial use or use within your organisation. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, all other rights are reserved. Requests and enquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to the Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions. NB: The spelling of some of the words for country, and species of plants and animals in language are different in various documents. This is primarily due to the fact that establishing a formal and consistent ‘sounds for spelling’ system for a language that did not have a written form takes time to develop and refine. -

Sidelights February 2013 the Council of American Master Mariners, Inc

NDED 19 FOU 36 $4.00 USD I February 2013 Vol. 43, No 1 NC 63 idelights OR 19 PORATED S Published by the Council of American Master Mariners, Inc. Register now for CAMM’s Professional Development Conference and AGM Piracy and Private Navies IOOS, NOAA Navigation Criminalization for the New Millenium ATB Quandary Mission Statement www.mastermariner.org The Council of American Master Mariners is dedicated to supporting and strengthening the United States Merchant Marine and the position of the Master by fostering the exchange of maritime information and sharing our experience. We are committed to the promotion of nautical education, the improvement of training standards, and the support of the publication of professional literature. The Council monitors, comments, and takes positions on local, state, federal and international legislation and regulation that affect the Master. · Mission-tested security teams · Strategically deployed operator MARITIME SECURITY SOLUTIONS support vessels WORLDWIDE · 24/7 manned mission operations centers · Threat analysis center · Route-specific intelligence assessments 13755 Sunrise Valley Drive, Suite 710 Herndon, VA 20171 USA Office: +1.703.657.0100 [email protected] AdvanFort.com IMLEA SAMI MSC Certified Member Executive Member In This Issue ON THE COVER SEABULK ARCTIC on the calm morning waters in Tampa Bay. Photo by Captain Terry Jednaszewski. View From the Bridge 7 Arctic Shipping and the Need for Emergency SIDELIGHTS 4605 NW 139th Loop Response Infrastructure CAMM National Vancouver, WA 98685 President R.J. Klein points out the seemingly 360-901-1257 obvious need for safety equipment and [email protected] services to support the growing Arctic EDITOR-IN-CHIEF shipping pushed by commercial interests. -

Strategic Environmental Assessment for the Orphan Basin

Orphan Basin Strategic Environmental Assessment Prepared by Prepared for Canada-Newfoundland Offshore Petroleum Board Fifth Floor, TD Place 140 Water Street St. John’s, NL A1C 6H6 11 November 2003 SA767 Orphan Basin Strategic Environmental Assessment Prepared by Prepared for Canada-Newfoundland Offshore Petroleum Board Fifth Floor, TD Place 140 Water Street St. John’s, NL A1C 6H6 11 November 2003 SA767 Orphan Basin Strategic Environmental Assessment Prepared by LGL Limited environmental research associates 388 Kenmount Road St. John’s, NL A1B 4A5 709 754-1992 (p) 709 754-7718 (f) Prepared for Canada-Newfoundland Offshore Petroleum Board Fifth Floor, TD Place 140 Water Street St. John’s, NL A1C 6H6 11 November 2003 SA767 Table of Contents Page Table of Contents........................................................................................................................................ ii List of Tables ............................................................................................................................................. xi List of Figures........................................................................................................................................... xii 1.0 Introduction..................................................................................................................................... 1 2.0 Oil and Gas Activities in Orphan Basin.......................................................................................... 3 2.1 Rights Issuance Process and Call for Bids......................................................................... -

Biodiversity of Michigan's Great Lakes Islands

FILE COPY DO NOT REMOVE Biodiversity of Michigan’s Great Lakes Islands Knowledge, Threats and Protection Judith D. Soule Conservation Research Biologist April 5, 1993 Report for: Land and Water Management Division (CZM Contract 14C-309-3) Prepared by: Michigan Natural Features Inventory Stevens T. Mason Building P.O. Box 30028 Lansing, MI 48909 (517) 3734552 1993-10 F A report of the Michigan Department of Natural Resources pursuant to National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Award No. 309-3 BIODWERSITY OF MICHIGAN’S GREAT LAKES ISLANDS Knowledge, Threats and Protection by Judith D. Soule Conservation Research Biologist Prepared by Michigan Natural Features Inventory Fifth floor, Mason Building P.O. Box 30023 Lansing, Michigan 48909 April 5, 1993 for Michigan Department of Natural Resources Land and Water Management Division Coastal Zone Management Program Contract # 14C-309-3 CL] = CD C] t2 CL] C] CL] CD = C = CZJ C] C] C] C] C] C] .TABLE Of CONThNTS TABLE OF CONTENTS I EXECUTIVE SUMMARY iii INTRODUCTION 1 HISTORY AND PHYSICAL RESOURCES 4 Geology and post-glacial history 4 Size, isolation, and climate 6 Human history 7 BIODWERSITY OF THE ISLANDS 8 Rare animals 8 Waterfowl values 8 Other birds and fish 9 Unique plants 10 Shoreline natural communities 10 Threatened, endangered, and exemplary natural features 10 OVERVIEW OF RESEARCH ON MICHIGAN’S GREAT LAKES ISLANDS 13 Island research values 13 Examples of biological research on islands 13 Moose 13 Wolves 14 Deer 14 Colonial nesting waterbirds 14 Island biogeography studies 15 Predator-prey -

Identification and Descriptions of Ecologically and Biologically Significant Areas in the Newfoundland and Labrador Shelves Bioregion

Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat (CSAS) Research Document 2017/013 Newfoundland and Labrador Region Identification and Descriptions of Ecologically and Biologically Significant Areas in the Newfoundland and Labrador Shelves Bioregion N.J. Wells, G.B. Stenson, P. Pepin, M. Koen-Alonso Science Branch Fisheries and Oceans Canada PO Box 5667 St. John’s, NL A1C 5X1 July 2017 Foreword This series documents the scientific basis for the evaluation of aquatic resources and ecosystems in Canada. As such, it addresses the issues of the day in the time frames required and the documents it contains are not intended as definitive statements on the subjects addressed but rather as progress reports on ongoing investigations. Research documents are produced in the official language in which they are provided to the Secretariat. Published by: Fisheries and Oceans Canada Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat 200 Kent Street Ottawa ON K1A 0E6 http://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/csas-sccs/ [email protected] © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, 2017 ISSN 1919-5044 Correct citation for this publication: Wells, N.J., Stenson, G.B., Pepin, P., and Koen-Alonso, M. 2017. Identification and Descriptions of Ecologically and Biologically Significant Areas in the Newfoundland and Labrador Shelves Bioregion. DFO Can. Sci. Advis. Sec. Res. Doc. 2017/013. v + 87 p. TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ............................................................................................................................... IV INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................1 -

Report on the Baxter Andrews Archaeology C O L L E C T I O N F R O M C a P E I S L a N D , N E W F O U N D L a N D

A REPORT ON THE BAXTER ANDREWS ARCHAEOLOGY C O L L E C T I O N F R O M C A P E I S L A N D , N E W F O U N D L A N D John Andrew Campbell Memorial University St. John’s, NL Community Collections Archaeological Research Project Volume 2 March 2016 With support from the Cultural Economic Development Program of the Department of Business, Tourism, Culture and Rural Development, Government of Newfoundland and Labrador. Finding new archaeological sites is not always an easy job. In this province, archaeological sites do not always leave obvious traces on the ground surface, and so archaeologists use many different approaches to finding new sites. Our techniques might involve the newest modern technology, but they will also certainly involve good old-fashioned field work, and often, a healthy dose of good luck. One of the most important ways that archaeologists can find new sites, though, is to talk to the people who live in and around the places that we work. Often, the archaeologist’s first approach when visiting a region to look for new sites is to find the nearest community, and ask as many people as possible a simple question: “do you know of any place nearby where old artifacts have been found?” The responses we get often lead to the discovery of undocumented archaeological sites, which we can add to the growing database that tracks this province’s cultural heritage. Documenting new sites means recording them in detail: we record a site’s general location on a map and its exact location with a GPS, its condition, how old we think the site might be, and the cultural group that used the site—which is more complicated than it might seem, given Newfoundland and Labrador’s lengthy and varied human history. -

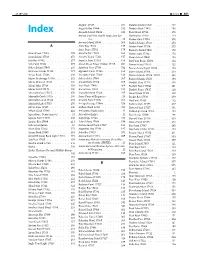

25 JUL 2021 Index Aaron Creek 17385 179 Aaron Island

26 SEP 2021 Index 401 Angoon 17339 �� � � � � � � � � � 287 Baranof Island 17320 � � � � � � � 307 Anguilla Bay 17404 �� � � � � � � � 212 Barbara Rock 17431 � � � � � � � 192 Index Anguilla Island 17404 �� � � � � � � 212 Bare Island 17316 � � � � � � � � 296 Animal and Plant Health Inspection Ser- Bar Harbor 17430 � � � � � � � � 134 vice � � � � � � � � � � � � 24 Barlow Cove 17316 �� � � � � � � � 272 Animas Island 17406 � � � � � � � 208 Barlow Islands 17316 �� � � � � � � 272 A Anita Bay 17382 � � � � � � � � � 179 Barlow Point 17316 � � � � � � � � 272 Anita Point 17382 � � � � � � � � 179 Barnacle Rock 17401 � � � � � � � 172 Aaron Creek 17385 �� � � � � � � � 179 Annette Bay 17428 � � � � � � � � 160 Barnes Lake 17382 �� � � � � � � � 172 Aaron Island 17316 �� � � � � � � � 273 Annette Island 17434 � � � � � � � 157 Baron Island 17420 �� � � � � � � � 122 Aats Bay 17402� � � � � � � � � � 277 Annette Point 17434 � � � � � � � 156 Bar Point Basin 17430� � � � � � � 134 Aats Point 17402 �� � � � � � � � � 277 Annex Creek Power Station 17315 �� � 263 Barren Island 17434 � � � � � � � 122 Abbess Island 17405 � � � � � � � 203 Appleton Cove 17338 � � � � � � � 332 Barren Island Light 17434 �� � � � � 122 Abraham Islands 17382 � � � � � � 171 Approach Point 17426 � � � � � � � 162 Barrie Island 17360 � � � � � � � � 230 Abrejo Rocks 17406 � � � � � � � � 208 Aranzazu Point 17420 � � � � � � � 122 Barrier Islands 17386, 17387 �� � � � 228 Adams Anchorage 17316 � � � � � � 272 Arboles Islet 17406 �� � � � � � � � 207 Barrier Islands 17433 -

Wind-Induced Barotropic Oscillations Around the Saint Pierre and Miquelon Archipelago (North-West Atlantic)

Continental Shelf Research 195 (2020) 104062 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Continental Shelf Research journal homepage: http://www.elsevier.com/locate/csr Research papers Wind-induced barotropic oscillations around the Saint Pierre and Miquelon archipelago (North-West Atlantic) M. Bezaud a,*, P. Lazure a, B. Le Cann b a IFREMER, Laboratoire d’Oc�eanographie Physique et Spatiale (LOPS), IUEM, Brest, France b CNRS, Laboratoire d’Oc�eanographie Physique et Spatiale (LOPS), IUEM, Brest, France ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: We investigate the nearly barotropic oscillations recently observed around the Saint Pierre and Miquelon (SPM) Barotropic modelling archipelago. They were recorded by two ADCPs at about 30 m depth during winter and spring 2014. These Wind induced oscillations oscillations were the dominant signal on the currents with a period of 2–4 days. Our analysis shows that these Continental shelf wave oscillations were triggered by the wind. To investigate these oscillations, a 2D numerical model was implemented Saint Pierre and Miquelon archipelago at a regional scale. The results from a realistic simulation confirmed the impact of wind forcing on ocean dy Newfoundland namics in the region. They also showed amplificationof these oscillations around SPM, particularly in the north- west of the archipelago and near Burin Peninsula. Analyses suggested the influence of continental shelf wave dynamics at a ‘regional’ scale. This regional wave then triggers a ‘local’ scale continental shelf wave propagating anticyclonically around SPM in ~2 days. Schematic modelling simulations with periodic wind stress forcing and relaxation after a gust of wind show a strong current response in this region with a wind stress periodicity centred around 2 days, which is attributed to resonance in the SPM area. -

Codes Used in the Newfoundland Commercial and Recreational Fisheries

Environment Canada Environnement Canada •• Fisheries Service des peches and Marine Service et des sciences de la mer 1 DFO ll ll i ~ ~~ll[lflll ~i~ 1 \11 1f1i! l1[1li eque 07003336 Codes Used in the Newfoundland Commercial and Recreational Fisheries by Don E. Waldron Data Record Series No. NEW/D-74-2 Resource Development Branch Newtoundland Region ) CODES USED IN THE NEWFOUNDLAND COMMERCIAL AND RECREATIONAL FISHERIES by D.E. Waldron Resource Development Branch Newfoundland Region Fisheries & Marine Service Department of the Environment St. John's, N'fld. February, 1974 GULF FlSHERIES LIBRARY FISHERIES & OCEANS gwt.IV HEOUE DES PECHES GOLFE' PECHES ET OCEANS ABSTRACT Data Processing is used by most agencies involved in monitoring the recreational and commercial fisheries of Newfoundland. There are three Branches of the Department of the Environment directly involved in Data Collection and Processing. The first two are the Inspection and the Conservation and Protection Branches (the collectors) and the Economics and Intelligence Branch (the processors)-is the third. To facilitate computer processing, an alpha-numeric coding system has been developed. There are many varieties of codes in use; however, only species, gear, ICNAF area codes, Economic and Intelligence Branch codes, and stream codes will be dealt with. Figures and Appendices are supplied to help describe these codes. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ........... .. ... .... ... ........... ................ ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS iv LIST .or FIGURES ....... .................................... v LIST OF TABLES ............................................ vi INTRODUCTION l Description of Data Coding .............. ~ .. .... ... 3 {A) Coding Varieties ••••••••••••••• 3 (I) Species Codes 3 ( II ) Gear Codes 3 (III) Area Codes 3 (i) ICNKF 4 (ii) Statistical Codes 7 (a) Statistical Areas 7 (b) Statistical Sections 7 (c) Community (Settlement) Codes 17 (iii) Comparison of ICNAF AND D.O.E. -

Total of 10 Pages Only May Be Xeroxed

CENTRE FOR NEWFOUNDLAND STUDIES TOTAL OF 10 PAGES ONLY MAY BE XEROXED (Without Author's Permission) '-- .. • CAPE COVE BEACH (DhAi-5,6,7), NEWFOUNDLAND: PREHISTORIC CULTURES by © Shaun Joseph Austin B.A., McMaster University, 1977 A Thesis Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS IN ANTHROPOLOGY Memorial University of Newfoundland July, 1980 ABSTRACT During the 1979 summer field season archaeological excavations were carried out at three prehistoric sites along Cape Cove Beach, on the northeast coast of the island of Newfoundland. Data gathered from these sites, coupled with existing evidence, have allowed inferences to be made concerning: 1) the nature of the terminal period of the Maritime Archaic Tradition; 2) the possibility of cross-cultural diffusion result- ing from contacts between Dorset Eskimo and Indian occupations in Newfoundland, between approximately 500 B.C. and A.D. 500; and, 3) the origin of the historic Beothuks. The Cape Cove-l site contained evidence of two separate Maritime Archaic occupations. The earlier of these two components represents one of the earliest known examples of human presence on the island of Newfoundland. The most significant artifacts recovered from this con- text are a slender chipped stone,contracting stemmed lance/spearhead, and two blade-like flakes. The second occupation at Cape Cove-l apparently followed a c. 925 year cultural hiatus. The most notable artifacts from this context include a unifacial scraper, ground stone adzes and celts, linear flakes, and several bifacially flaked projectile points. The Cape Cove-2 site contained one major prehistoric Beothuk com- ponent.