“Private Banking and Money Laundering: a Case Study of Opportunities and Vulnerabilities,” S.Hrg

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bank Code Finder

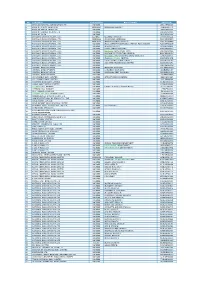

No Institution City Heading Branch Name Swift Code 1 AFRICAN BANKING CORPORATION LTD NAIROBI ABCLKENAXXX 2 BANK OF AFRICA KENYA LTD MOMBASA (MOMBASA BRANCH) AFRIKENX002 3 BANK OF AFRICA KENYA LTD NAIROBI AFRIKENXXXX 4 BANK OF BARODA (KENYA) LTD NAIROBI BARBKENAXXX 5 BANK OF INDIA NAIROBI BKIDKENAXXX 6 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. ELDORET (ELDORET BRANCH) BARCKENXELD 7 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. MOMBASA (DIGO ROAD MOMBASA) BARCKENXMDR 8 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. MOMBASA (NKRUMAH ROAD BRANCH) BARCKENXMNR 9 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. NAIROBI (BACK OFFICE PROCESSING CENTRE, BANK HOUSE) BARCKENXOCB 10 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. NAIROBI (BARCLAYTRUST) BARCKENXBIS 11 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. NAIROBI (CARD CENTRE NAIROBI) BARCKENXNCC 12 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. NAIROBI (DEALERS DEPARTMENT H/O) BARCKENXDLR 13 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. NAIROBI (NAIROBI DISTRIBUTION CENTRE) BARCKENXNDC 14 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. NAIROBI (PAYMENTS AND INTERNATIONAL SERVICES) BARCKENXPIS 15 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. NAIROBI (PLAZA BUSINESS CENTRE) BARCKENXNPB 16 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. NAIROBI (TRADE PROCESSING CENTRE) BARCKENXTPC 17 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. NAIROBI (VOUCHER PROCESSING CENTRE) BARCKENXVPC 18 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. NAIROBI BARCKENXXXX 19 CENTRAL BANK OF KENYA NAIROBI (BANKING DIVISION) CBKEKENXBKG 20 CENTRAL BANK OF KENYA NAIROBI (CURRENCY DIVISION) CBKEKENXCNY 21 CENTRAL BANK OF KENYA NAIROBI (NATIONAL DEBT DIVISION) CBKEKENXNDO 22 CENTRAL BANK OF KENYA NAIROBI CBKEKENXXXX 23 CFC STANBIC BANK LIMITED NAIROBI (STRUCTURED PAYMENTS) SBICKENXSSP 24 CFC STANBIC BANK LIMITED NAIROBI SBICKENXXXX 25 CHARTERHOUSE BANK LIMITED NAIROBI CHBLKENXXXX 26 CHASE BANK (KENYA) LIMITED NAIROBI CKENKENAXXX 27 CITIBANK N.A. NAIROBI NAIROBI (TRADE SERVICES DEPARTMENT) CITIKENATRD 28 CITIBANK N.A. -

Legal Innovation and State Competition for Corporate Charters

The States as a Laboratory: Legal Innovation and State Competition for Corporate Charters Roberta Romanot Corporate law is an arena in which the metaphor of the "states as a laboratory" describes actual practice, and, for the most part, this is a laboratory that has worked reasonably well. The goal of this Article is to map out over time the diffusion of corporate law reforms across the states. The law- making pattern we observe indicates a dynamic process in which legal innovations originate from several sources, creating a period of legal experimentation that tends to identify a statutoryformulation that is thereafter adopted by the vast majority of states. Delaware and the Model Act quite often work in tandem. But there are occasions when they advance differing legal rules, accounting for some of the diversity in corporation codes that we observe. Introduction ..................................................................................................... 2 10 I. Key Features of U.S. Corporate Law ........................................................ 212 II. The Laboratory of State Competition for Charters ................................... 214 A. The Diffusion of CorporateLaw Reforms .......................................... 216 1. The Drive for Greater Organizational Flexibility and Delaware's 1967 Code Revision ................................................. 216 2. The D & 0 Insurance Crisis and Limitations on Directors' L iab ility ...................................................................................... -

The Price Riggs Paid

REPUTATION DAMAGE: The Price Riggs Paid A Case Study prepared by World-Check, the market pioneer and industry standard for PEP screening and customer due diligence — serving over 1,600 financial institutions and government agencies in more than 120 countries, including 45 of the world’s 50 largest financial institutions. © 2006 World-Check (Global Objectives Ltd) All Rights Reserved. For permission to re-publish in whole or part please email [email protected] World-Check is a registered trademark. Reputation Damage: ‘ The Price Riggs Paid’ CONTENT: Section Page FOREWORD: By David B. Caruso Former Executive Vice President of Compliance & Security at Riggs Bank INTRODUCTION: RIGGS: ‘Things fall apart’ 1 UNDERSTANDING THE ISSUES AT RIGGS: 2 TWO LEADERS, TOO MANY? 2 • RIGGS & PINOCHET 2 • RIGGS & OBIANG 3 PRIOR TO ITS ‘PRESIDENTIAL PROBLEMS’ 4 THE SAUDI ARABIAN DIPLOMATIC ACCOUNTS 4 THE RESULTS: 5 SHAREHOLDER SUITS AND FINES. 5 RENEGOTIATING THE MERGER. 8 UNDERSTANDING THE EFFECTS: 8 REPUTATION FALLOUT 8 TIMELINE 10 LESSONS TO BE LEARNT 11 WORLD-CHECK: AN OVERVIEW FOREWORD by David B. Caruso Former Executive Vice President of Compliance & Security at Riggs Bank Riggs is a story about the price paid when an Anti-Money Laundering ("AML") compliance program lacks proper oversight by management and the board of directors. As you will read in this paper the outcome of such failure in the case of Riggs was rather dramatic and as in any good drama there were lots of twists and turns in the various plots and sub-plots. Who could have imagined that one, relatively small bank in Washington DC, could have participated in the questionable financial activities of two of the more notorious dictators of the last quarter century? One of the many thing my staff and I learned over the two years we were at Riggs busy trying to build a compliance program and ultimately uncovering almost all of the facts you'll read about in this paper, is how harmless most poor business decisions seem at the time they are made. -

Profile Oneibc Final

UV định hình UV định hình UV định hình UV định hình In today’s global marketplace, globalization, technological advances, and demographic shifts have brought opportunities to many - empowering and connecting people then creating a vibrant and diverse world. The business success increasingly requires active trading participation in foreign markets. Emerging companies typically operate in rapidly evolving industries where expertise, speed and efficiency are rewarded. Clients look to One IBC to consult clients through the complexities, we are The Trust and Company Service Provider in safeguarding the clients from the risks so that there are no limitation for their success. Together with an in-depth knowledge of international jurisdiction, One IBC provides expertise and support our clients as they conduct their business in global smoothly. Whether you are doing business in Europe, Asia, Africa, the Middle East, the Americas or elsewhere, One IBC will set up the best trading or holding structure for your business in line with local laws and regulations. We also have the necessary expertise in the administrative support and managing companies to maximize opportunities and achieve long - term sustainability, from fullback office solutions to assist with tax and regulatory compliance. To reach our ambition, we are making significant changes to how we operate our business so that we have the highest-performing teams, delivering professional client services worldwide. I would like to thank our clients and partners for their continued support, trust “Closely monitoring changes global environment and understanding in the future. and the need of the clients, One IBC Group in creating new business opportunities and pursue growth strategies.” One IBC Limited stands for One International Business Consultancy. -

Provider Id Provider Name 00203Ea2-8Be5-434B-82Aa

Provider Id Provider Name 00203ea2-8be5-434b-82aa-a968cdccc71c Centric Bank 002b95bb-472e-4316-8e26-eefcb26af6dd Northland Area Federal Credit Union (MI) 004139df-1233-4846-8007-655902d283f3 Forte Bank - Business 005119b7-d11b-4149-8875-d810ce1119f7 Town & Country Bank - UT 00678017-3dd3-48d9-96dd-49f2a75df3ad Fulton Financial CashLink East 00686d39-a1ca-4a18-bb42-88c5e9af95e4 Iowa Nebraska State Bank(Now BankFirst (NE)) 006ccff2-c2b5-461b-93fe-a345efdbf885 Lanco FCU 0080f77d-a78c-41e8-b9c4-8d49cdec1f6a Boat U.S. MBNA CC 0093d12e-d5de-456c-a1d8-f10770405be9 1st Bank of Sea Isle City - Business Banking 009515cf-b944-4002-88fe-66aaeace40ed Citizens Bank & Trust (OK) 00c5e357-6071-4a90-ac44-4eb96183e162 First Utah Bank 00cdd410-208a-47dd-bc29-a9627cadf68f Sentry Bank 00f83a8c-5959-4604-a7ec-bd00583ad99f Farmers State Bank (IN) 0122685c-3eaa-4a8a-ab9c-616ba5f6b24e Home Federal Savings and Loan Association of Collinsville 014c1f5b-0bd5-45a7-b648-86f4c869b01b Grasslands Federal Credit Union 0169eb89-0c80-445d-a13a-8933b512d4cf ZZ OGRAF SLLEW 016afc49-673c-4f09-b3d5-f24a7a1eea24 Atlantic Capital Bank (GA) Sun West Bank, Las Vegas NV - Business Banking (Now City National 016d3ab7-b5d3-482a-8767-822372a1e380 Bank, CA - Business Online) 0176b604-c675-4412-a792-8d1578bdf48c First Port City Bank (GA) 017aeb6a-9d51-4c9b-8ead-b8d3a5a95f53 First National Bank and Trust (FL) 019e9909-f57d-4e3c-b494-751939a0c234 First National Bank Minnesota - Business Banking 01a03d99-694c-4888-a79a-5bcf3ae3e650 First Iowa State Bank Albia 01ab7eee-ec30-49b9-8476-4804f34abb31 -

TARIFF TYPE of SERVICE REMARKS CURRENT CHARGES (W.E.F 01.11.2015) BANKERS CHEQUE Customers (Debit to A/C) Kshs

Your Preferred Bank TARIFF TYPE OF SERVICE REMARKS CURRENT CHARGES (W.E.F 01.11.2015) BANKERS CHEQUE Customers (debit to A/C) Kshs. 350/- Customers (depositing cash) Kshs. 600/- plus cash handling charges Non-Customers Kshs. 600/- plus cash handling charges DRAFTS Customers Kshs. 600/- Non-Customers Kshs. 750/- CHEQUE BOOKS 25 Leaves Kshs. 437.50 (local and foreign currency) 50 Leaves Kshs. 875/- 100 Leaves Kshs. 1,750/- (above charges are inclusive of Stamp Duty of Kshs. 2.50) COUNTER CHEQUES Per leaf Kshs. 50.00 (inclusive of Stamp Duty of Kshs. 2.50) UNPAID CHEQUES Financial reasons Kshs. 1,350/- (INWARD & OUTWARD) Technical reasons Kshs. 1,000/- STOP PAYMENT OF CHEQUES Notification charges - local cheques Kshs. 270/- - foreign cheques Kshs. 1,500/- RTGS CHARGES Inward Free Outward Kshs.600/- EFT CHARGES Inward Free Outward Kshs. 300/- TT CHARGES (FOREIGN) Beneficiary to share charges with the Kshs. 1,500/- remitter Beneficiary to receive full amount Kshs. 3,000/- Indian Rupee TT / ZAR Kshs. 2,000/- TT Amendment Charges / Tracers USD. 55/- irrespective of the currency TT PAYMENTS (LOCAL) Third party to collect Kshs. 1,000/- INCOMING FUNDS USD $ 10.00 GBP Equivalent $ 10.00 EUR Equivalent $ 10.00 ACCOUNTS 1) Current Account: Kshs. 10,000/- Minimum Balance Kshs. 275/- Surcharge per month for non-compliance of minimum balance Kshs. 20/- per entry, minimum Kshs 500/- ledger fees per month 2) Foreign Currency Accounts Accounts available in USD, GBP, EUR and Rand 3) Chemi Chemi Accounts Kshs. 5,000/- Minimum Balance for Personal Account Kshs. 1,000/- Minimum Balance for Wananchi Account Kshs. -

2 Giro Commercial Bank Ltd Was Acquired by I&M Bank Limited

COMMERCIAL BANKS WEIGHTED AVERAGE LENDING RATES PER LOAN CATEGORY AND MATURITY (%) Loan Category PERSONAL BUSINESS CORPORATE OVERALL RATES Loan Maturity Overdraft 1-5 Years Over 5 years Overdraft 1-5 Years Over 5 years Overdraft 1-5 Years Over 5 years 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 Banks Dec-16 Mar-171 Jun-171 Dec-16 Mar-171 Jun-171 Dec-16 Mar-171 Jun-171 Dec-16 Mar-171 Jun-171 Dec-16 Mar-171 Jun-171 Dec-16 Mar-171 Jun-171 Dec-16 Mar-171 Jun-171 Dec-16 Mar-171 Jun-171 Dec-16 Mar-171 Jun-171 Dec-16 Mar-171 Jun-171 1 Africa Banking Corporation Ltd 14.1 13.5 13.1 14.0 13.1 13.7 13.9 13.7 13.9 14.2 12.8 13.7 14.1 13.2 13.8 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.3 13.5 13.7 14.1 12.0 13.70 14.0 13.3 13.7 14.1 13.1 13.7 2 Bank of Africa Kenya Ltd 14.0 14.0 14.0 13.9 13.9 13.9 14.0 14.0 14.0 13.9 13.9 13.9 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 13.8 14.0 14.0 13.8 13.8 13.75 14.0 14.0 14.0 13.9 13.9 13.9 3 Bank of Baroda (K) Ltd 14.0 13.8 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 13.9 13.9 13.9 13.9 13.9 13.9 14.0 14.0 14.0 13.9 13.9 13.9 13.9 13.9 13.93 14.0 14.0 14.0 13.9 13.9 13.9 4 Bank of India 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.00 14.0 14.0 13.9 14.0 14.0 14.0 5 Barclays Bank of Kenya Ltd 14.0 14.0 13.5 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 13.8 13.4 13.5 14.0 13.8 13.9 13.8 13.4 13.7 13.7 13.6 12.7 13.4 13.3 13.33 13.6 13.4 13.5 13.8 13.7 13.8 6 Stanbic Bank Kenya Ltd 13.9 13.8 10.3 13.9 13.8 13.6 13.9 13.9 13.6 12.6 13.7 10.2 13.9 13.9 13.4 13.7 13.8 13.9 12.3 12.7 10.3 13.3 13.3 13.97 14.0 14.0 14.0 13.3 13.6 -

Bank Supervision Annual Report 2019 1 Table of Contents

CENTRAL BANK OF KENYA BANK SUPERVISION ANNUAL REPORT 2019 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS VISION STATEMENT VII THE BANK’S MISSION VII MISSION OF BANK SUPERVISION DEPARTMENT VII THE BANK’S CORE VALUES VII GOVERNOR’S MESSAGE IX FOREWORD BY DIRECTOR, BANK SUPERVISION X EXECUTIVE SUMMARY XII CHAPTER ONE STRUCTURE OF THE BANKING SECTOR 1.1 The Banking Sector 2 1.2 Ownership and Asset Base of Commercial Banks 4 1.3 Distribution of Commercial Banks Branches 5 1.4 Commercial Banks Market Share Analysis 5 1.5 Automated Teller Machines (ATMs) 7 1.6 Asset Base of Microfinance Banks 7 1.7 Microfinance Banks Market Share Analysis 9 1.8 Distribution of Foreign Exchange Bureaus 11 CHAPTER TWO DEVELOPMENTS IN THE BANKING SECTOR 2.1 Introduction 13 2.2 Banking Sector Charter 13 2.3 Demonetization 13 2.4 Legal and Regulatory Framework 13 2.5 Consolidations, Mergers and Acquisitions, New Entrants 13 2.6 Medium, Small and Micro-Enterprises (MSME) Support 14 2.7 Developments in Information and Communication Technology 14 2.8 Mobile Phone Financial Services 22 2.9 New Products 23 2.10 Operations of Representative Offices of Authorized Foreign Financial Institutions 23 2.11 Surveys 2019 24 2.12 Innovative MSME Products by Banks 27 2.13 Employment Trend in the Banking Sector 27 2.14 Future Outlook 28 CENTRAL BANK OF KENYA 2 BANK SUPERVISION ANNUAL REPORT 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER THREE MACROECONOMIC CONDITIONS AND BANKING SECTOR PERFORMANCE 3.1 Global Economic Conditions 30 3.2 Regional Economy 31 3.3 Domestic Economy 31 3.4 Inflation 33 3.5 Exchange Rates 33 3.6 Interest -

Chapter 1: Choosing the Form of Business

Law 451 Corporations (O’Byrne) Chapter 1: Choosing the Form of Business Vehicle _______________________________________________ 7 Types of Business Vehicles ________________________________________________________________________ 7 Sole Proprietorship _______________________________________________________________________________________ 8 Corporation _____________________________________________________________________________________________ 9 Unlimited Liability Corporation (ULC) _____________________________________________________________________ 10 Partnership ____________________________________________________________________________________________ 10 General _____________________________________________________________________________________________ 10 Ordinary Partnership __________________________________________________________________________________ 10 Limited Partnership (“LP”) ______________________________________________________________________________ 11 Limited Liability Partnership (“LLP”) ______________________________________________________________________ 11 Joint Ventures __________________________________________________________________________________________ 12 Agency _______________________________________________________________________________________ 12 Agency and Business Law _________________________________________________________________________________ 12 Types of Authority ____________________________________________________________________________________ 12 Liability _____________________________________________________________________________________________ -

Part 3. Where Does the Beneficial Owner Hide?

Part 3. Where Does the Benefi cial Owner Hide? “Vice knows she’s ugly, so puts on her mask.” — Benjamin Franklin 3.1 Introduction Th is study revealed that, in the vast majority of grand corruption cases we analyzed, corporate vehicles—including companies, trusts, foundations, and fi ctitious entities— are misused to conceal the identities of the people involved in the corruption. Of these corporate vehicles, the company was the most frequently used. Investigators confi rmed this misuse, noting that locating information about the person who is in control of a corporate vehicle was essential to any large-scale corruption investigation, and indeed, to almost any large-scale organized-crime investigation. Despite the widespread misuse of corporate vehicles for criminal purposes (including corruption, fi nancing terrorism, money laundering, and fraud), most countries have no coherent strategy to tackle this problem. Th is chapter identifi es the types of corporate vehicles used to conceal the identity of the person involved in the corruption and other obstacles that investigators may face. An overview of each of these corporate vehicles is given in appendix C. 3.2 Corporate Vehicles: Types and Features Th is section describes the various types of corporate vehicles that have been used in grand corruption schemes. We distinguish four distinct categories: • Companies • Trusts • Foundations • Fictitious entities and unincorporated economic organizations. (Fictitious entities is an outlier category, encompassing sole proprietorships, the vari- ous forms of partnerships, and other functionally eff ective equivalents.) We provide an overview of the main characteristics of these corporate vehicles. Th eir precise nature, the ways in which they are misused for criminal ends, and the extent to which they are misused vary from jurisdiction to jurisdiction; nonetheless, our study revealed a num- ber of global similarities. -

WRITTEN STATEMENT of RIGGS BANK N.A. to the PERMANENT SUBCOMMITTEE on INVESTIGATIONS of the COMMITTEE on GOVERNMENTAL AFFAIRS Of

WRITTEN STATEMENT OF RIGGS BANK N.A. to the PERMANENT SUBCOMMITTEE ON INVESTIGATIONS of the COMMITTEE ON GOVERNMENTAL AFFAIRS of the UNITED STATES SENATE July 15, 2004 I. Introduction. Riggs Bank has been privileged to serve the banking needs of our nation’s capital for nearly two centuries. During that time, Riggs has served such historical figures as President Abraham Lincoln and American Red Cross founder Clara Barton. Riggs also has assisted in some important historical transactions, such as supplying the gold for the purchase of the State of Alaska. Today, Riggs is the oldest independent bank headquartered in Washington, D.C., serving the District and the surrounding metropolitan area with more than 45 branch locations. Without a doubt, this past year has been among the most challenging in the Bank’s long and storied history. We will address today some of those challenges and how the Bank is moving to address them, and will address questions raised in the letter from Chairman Coleman and Senator Levin. Looking back, it is clear that Riggs did not accomplish all that it needed to. Specifically, with respect to the improvements that were outlined by the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (“OCC”) in its examinations, Riggs deeply regrets that it did not more swiftly and more thoroughly complete the work necessary to meet fully the expectations of its regulators. For this, the Bank accepts full responsibility. Looking forward, Riggs is acting forcefully to comply with all federal rules and regulations and is cooperating as fully as possible with all appropriate agencies and congressional committees looking into these matters. -

The Effect of Corporate Social Responsibility (Csr) on Profitability of Commercial Banks in Kenya

THE EFFECT OF CORPORATE SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY (CSR) ON PROFITABILITY OF COMMERCIAL BANKS IN KENYA ONGWAE ELKANAH MUMA A RESEARCH PROPOSAL PRESENTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF MASTER BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION, SCHOOL OF BUSINESS UNIVERSITY OF NAIROBI SEPTEMBER 2016 DECLARATION I hereby declare that this project is my own work and effort and it has not been presented in any other university anywhere for an academic award. ONGWAE ELKANAH MUMA D61/79084/2015 SIGN............................................. Date………………………………… This research project has been submitted for examination with my approval as the candidate's university supervisor. Signed............................................ Date.................................................... Dr. Duncan Elly Ochieng (PhD, CIFA) Lecturer, Department of Finance & Accounting, School of Business ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I am thankful to God for the giving me the strength and capacity to finish this project. My appreciation goes to my supervisor, Dr. Duncan Elly Ochieng, for his taking his time to provide guidance for my project. I also acknowledge my colleagues, Mercy Atieno and Steven Kariuki, for helping me obtain data. I acknowledge Lecturers in University of Nairobi’s Business School for the part they played to enable me complete this research. May God bless you abundantly. iii DEDICATION This job is dedicated to my grandmother, the late Rhoda Kerubo, for instilling in me the culture of hard work and the significance of learning from a young age. May her soul rest in peace. I also dedicate this work to my mother Franciscah Kwamboka, my supportive sister Carol Ongwae and my guardian Naftali Okong’o. May this work motivate you achieve great accomplishments.