This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Iconography of the Recently Discovered Naga Sculptures from Pamba River Basin, Pathanamthitta District, South Kerala

Iconography of the Recently Discovered Naga Sculptures from Pamba River Basin, Pathanamthitta District, South Kerala Ambily C.S.1, Ajit Kumar2 and Vinod Pancharath3 1. Excavation Branch II, Archaeological survey of India, Purana Qila, New Delhi – 110001, India (Email: [email protected]) 2. Department of Archaeology, University of Kerala, Kariavattom Campus, Thiruvananthapuram - 695581, Kerala, India (Email: [email protected]) 3. Industrial Design Centre, Indian Institute of Technology, Powai, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India (Email: [email protected]) Received: 25 September 2015; Accepted: 18 October 2015; Revised: 09 November 2015 Heritage: Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies in Archaeology 3 (2015): 618-634 Abstract: Recent exploration by the first author brought to light interesting Naga sculptures from the middle ranges of Pamba River basin. All the sculptures are made out of granite and can be classified into Nagarajas and Nagayakshis except one which is a female naga devotee. This paper tries to briefly discuss the iconography, chronology and significance of the sculptures. Keywords: Exploration, Pamba River Basin, Kerala, Nagarajas, Nagayakshis, Iconography, Chronology Introduction Pamba is one of the important and third longest rivers in Kerala. It is apparently the river Baris/Bans mentioned in records of Pliny (Menon 1967-62). It originates from Pulachimalai hill in Peermade plateau at an altitude of 1650 MSL and has a length of 176km. It flows through Idukki, Pathanamthitta and Alappuzha districts and finally empties into the Vembanadu Lake. During medieval period Pamba basin harbored prosperous settlement like Kaviyur, Thiruvanmandoor, Perunnayil and Thiruvalla. Naga and yakshi images have earlier been reported from Niranam-Tiruvalla area (Mathew 2006). The present discoveries add to the list of known images. -

Dharmic Environmentalism: Hindu Traditions and Ecological Care By

Dharmic Environmentalism: Hindu Traditions and Ecological Care by © Rebecca Cairns A Thesis submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, Memorial University, Religious Studies Memorial University of Newfoundland August, 2020 St. John’s, Newfoundland and Labrador ABstract In the midst of environmental degradation, Religious Studies scholars have begun to assess whether or not religious traditions contain ecological resources which may initiate the restructuring of human-nature relationships. In this thesis, I explore whether it is possible to locate within Hindu religious traditions, especially lived Hindu traditions, an environmental ethic. By exploring the arguments made by scholars in the fields of Religion and Ecology, I examine both the ecological “paradoxes” seen by scholars to be inherent to Hindu ritual practice and the ways in which forms of environmental care exist or are developing within lived religion. I do the latter by examining the efforts that have been made by the Bishnoi, the Chipko Movement, Swadhyay Parivar and Bhils to conserve and protect local ecologies and sacred landscapes. ii Acknowledgements I express my gratitude to the supportive community that I found in the Department of Religious Studies. To Dr. Patricia Dold for her invaluable supervision and continued kindness. This project would not have been realized without her support. To my partner Michael, for his continued care, patience, and support. To my friends and family for their encouragement. iii List of Figures Figure 1: Inverted Tree of Life ……………………. 29 Figure 2: Illustration of a navabatrikā……………………. 34 Figure 3: Krishna bathing with the Gopis in the river Yamuna. -

Online Seat Allotment - 2021 Department of Education Administration of UT of Lakshadweep

Online Seat Allotment - 2021 Department of Education Administration of UT of Lakshadweep College Wise Balance Seats Course Name College Name Total Seats Available Seats Ayurveda Nurse (12 Months Directorate of Ayurveda Medical Education, Trivandrum 2 0 Diploma Course) Ayurveda Pharmacist (12 Months Directorate of Ayurveda Medical Education, Trivandrum 2 0 Diploma Course) Ayurveda Therapist (12 Months Directorate of Ayurveda Medical Education, Trivandrum 2 0 Diploma Course) Craftmanship (One year) Institute of Hotel Management Catering Technology & Applied 10 0 Nutrition, Chennai Diploma in Civil Engineering Directorate of Technical Education, Guindy, Chennai 3 0 Diploma in Civil Engineering Govt. Polytechnic College, Kalamassery 3 0 Diploma in Civil Engineering Govt. Polytechnic College, Kozhikode 3 0 Diploma in Civil Engineering Training Institute, Gujarat 1 0 Diploma in Electrical & Directorate of Technical Education, Guindy, Chennai 11 0 Electronics Diploma in Electrical & Govt. Polytechnic College, Kalamassery 2 0 Electronics Diploma in Electrical & Govt. Polytechnic College, Kozhikode 2 0 Electronics Diploma in Electronics & Directorate of Technical Education, Guindy, Chennai 3 0 Communication Diploma in Electronics Engg. Govt. Polytechnic, Kannur 2 0 Diploma in Mechanical Engg. Directorate of Technical Education, Guindy, Chennai 9 0 Diploma in Mechanical Engg. Govt. Polytechnic College, Kalamassery 3 0 Diploma in Mechanical Engg. Govt. Polytechnic College, Kozhikode 2 0 Diploma in Printing Technology Training Institute, Gujarat 1 1 Electronics & Instruments Directorate of Technical Education, Guindy, Chennai 5 0 Shore Mechanic Course (SMC) Central Institute of Fisheries Nautical and Engineering 22 0 Training (CIFNET), Chennai Stenographer & Secretarial Govt. ITI, Chalakkudi 1 0 Assistant (English) Surveyor Govt. ITI, Chalakkudi 2 0 Electronics Mechanic Govt. ITI, Kalamassery 1 0 Electronics Mechanic Govt. -

Particulars of Some Temples of Kerala Contents Particulars of Some

Particulars of some temples of Kerala Contents Particulars of some temples of Kerala .............................................. 1 Introduction ............................................................................................... 9 Temples of Kerala ................................................................................. 10 Temples of Kerala- an over view .................................................... 16 1. Achan Koil Dharma Sastha ...................................................... 23 2. Alathiyur Perumthiri(Hanuman) koil ................................. 24 3. Randu Moorthi temple of Alathur......................................... 27 4. Ambalappuzha Krishnan temple ........................................... 28 5. Amedha Saptha Mathruka Temple ....................................... 31 6. Ananteswar temple of Manjeswar ........................................ 35 7. Anchumana temple , Padivattam, Edapalli....................... 36 8. Aranmula Parthasarathy Temple ......................................... 38 9. Arathil Bhagawathi temple ..................................................... 41 10. Arpuda Narayana temple, Thirukodithaanam ................. 45 11. Aryankavu Dharma Sastha ...................................................... 47 12. Athingal Bhairavi temple ......................................................... 48 13. Attukkal BHagawathy Kshethram, Trivandrum ............. 50 14. Ayilur Akhileswaran (Shiva) and Sri Krishna temples ........................................................................................................... -

The First Report of the Malabar Puffer, Carinotetraodon Travancoricus

Journal on New Biological Reports 1(2): 42-46 (2012) ISSN 2319 – 1104 (Online) The first report of the Malabar puffer, Carinotetraodon travancoricus (Hora & Nair, 1941) from the Neyyar wildlife sanctuary with a note on its feeding habit and length-weight relationship G. Prasad*, K. Sabu and P.V. Prathibhakumari Laboratory of Conservation Biology, Department of Zoology, University of Kerala, Kariavattom, Thiruvananthapuram 695 581, Kerala, India (Received on: 20 October, 2012; accepted on: 2 November, 2012) ABSTRACT Carinotetraodon travancoricus, the Malabar puffer fish has been collected and reported for first time from the Kallar stream, Neyyar Wildlife Sanctuary of southern part of Kerala. The food and feeding habit and length-weight relationship of the fish also has been studied and presented. Key words : Carinotetraodon travancoricus, Neyyar Wildlife Sanctuary, Kallar stream, length- weight relationship INTRODUCTION The Western Ghats of India along with Sri Lanka is Carinotetraodon travancoricus commonly considered as one of the biodiversity hotspots of the known as Malabar puffer fish inhabits in freshwater world (Mittermeier et al. 1998; Myers et al. 2000). and estuaries which is endemic to Kerala and This mountain range extends along the west coast of Karnataka (Talwar & Jhingran 1991; Jayaram 1999; India and is crisscrossed with many streams, which Remadevi 2000). Carinotetraodon travancoricus was form the headwaters of several major rivers draining first described from Pamba River by Hora & Nair water to the plains of peninsular India. The Ghats is a (1941). This fish is present in 13 rivers of Kerala critical ecosystem due to its high human population including Chalakudy, Pamba, Periyar, Kabani, pressure (Cincotta et al. -

Socio-Political Movements in North Bengal -..:: Global Group Of

Socio-Political Movements in North Bengal (A Sub-Himalayan Tract) Edited by Publish by Global Vision Publishing House Sukhbilas Barma Greater Kuch Bihar—A Utopian Movement? Sukhbilas Barma IT HAS happened every now and then—one movement followed by the other. This part of the country popularly known as North Bengal, inhabited by the major ethnic group of people, the Rajbanshis, has gone through different phases of various movements and mainly ethnic movements. One can be reminded of the Uttar Khanda movement, a movement of a section of the Rajbanshis led by Panchanan Mallik. The movement was basically on the socio-economic- political issues, the feeling of deprivation of the sons of the soil. This continued for some time; the Government paid some amount of attention to the problems of the region; people got swayed by the left ideologies, and the movement lost ground. Then came Kamtapuri movement in late 90’s, based on ethnic sentiments, which were related primarily to the feeling of subordination of the Rajbanshi language and culture. Based on the linguistic theory propounded by Dharmanarayan Barma, the leaders of Kamtapuri movement led by Atul Roy shook the socio-political environment of Dr. Sukhbilas Barma: A retired I.A.S Officer, Dr. Barma held important positions in the Government of west Bengal. 336 Socio-Political Movements in North Bengal North Bengal vigorously. The well-off sections of the Rajbanshis have lost their lands and prestige to the non- Rajbanshis hailing from East Pakistan. The poverty stricken youths have had to leave their mother land in search of livelihood. -

KERALA SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT PROJECT (KSWMP) with Financial Assistance from the World Bank

KERALA SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT Public Disclosure Authorized PROJECT (KSWMP) INTRODUCTION AND STRATEGIC ENVIROMENTAL ASSESSMENT OF WASTE Public Disclosure Authorized MANAGEMENT SECTOR IN KERALA VOLUME I JUNE 2020 Public Disclosure Authorized Prepared by SUCHITWA MISSION Public Disclosure Authorized GOVERNMENT OF KERALA Contents 1 This is the STRATEGIC ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT OF WASTE MANAGEMENT SECTOR IN KERALA AND ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL MANAGEMENT FRAMEWORK for the KERALA SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT PROJECT (KSWMP) with financial assistance from the World Bank. This is hereby disclosed for comments/suggestions of the public/stakeholders. Send your comments/suggestions to SUCHITWA MISSION, Swaraj Bhavan, Base Floor (-1), Nanthancodu, Kowdiar, Thiruvananthapuram-695003, Kerala, India or email: [email protected] Contents 2 Table of Contents CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION TO THE PROJECT .................................................. 1 1.1 Program Description ................................................................................. 1 1.1.1 Proposed Project Components ..................................................................... 1 1.1.2 Environmental Characteristics of the Project Location............................... 2 1.2 Need for an Environmental Management Framework ........................... 3 1.3 Overview of the Environmental Assessment and Framework ............. 3 1.3.1 Purpose of the SEA and ESMF ...................................................................... 3 1.3.2 The ESMF process ........................................................................................ -

Rain 11 08 2019.Xlsx

Rainfall in 'mm' on 11.08.2019 District River Basin Station Name 11-08-2019 Alappuzha Achencovil Kollakadavu 55.2 Alappuzha Manimala Ambalapuzha 99.3 Alappuzha Muvattupuzha Arookutty 114.4 Alappuzha Muvattupuzha Cherthala 108 Cannanore Anjarakandy Cheruvanchery 96 Cannanore Anjarakandy F.c.s. Pazhassi 93 Cannanore Anjarakandy Kottiyoor 176 Cannanore Anjarakandy Kannavam 72 Cannanore Karaingode Pulingome 167.4 Cannanore Kuppam Alakkode 148.6 Cannanore Peruvamba Kaithaprem 116.2 Cannanore Peruvamba Olayampadi 144.6 Cannanore Ramapuram Cheruthazham 70.2 Cannanore Anjarakandy Maloor 104 Cannanore Valapattanam Mangattuparamba 58.6 Cannanore Anjarakandy Nedumpoil 77.2 Cannanore Valapattanam Palappuzha 80 Cannanore Valapattanam Payyavoor 140 Cannanore Kuppam Alakkode 148.6 Cannanore Valapattanam Thillenkeri 121 Ernakulam Muvattupuzha Piravam 87.2 Ernakulam Periyar Aluva 112.5 Ernakulam Periyar Boothathankettu 79.6 Ernakulam Periyar Keerampara 63.2 Ernakulam Periyar Neriyamangalam 69.8 Idukki Manimala Boyce estate 47 Idukki Muvattupuzha Vannapuram 54.3 Idukki Pambar Marayoor 5.6 Idukki Periyar Chinnar 37 Idukki Periyar FCS Painavu 32.4 Idukki Periyar Kumali 27 Idukki Periyar Nedumkandam 23.8 Idukki Periyar Vandanmedu 34.8 Kasaragod Chandragiri Vidhyanagar 161.8 Kasaragod Chandragiri Kalliyot 142.3 Kasaragod Chandragiri Padiyathadukka 126.4 Kasaragod Karaingode Kakkadavue(cheemeni)fcs 141.8 Kasaragod Manjeswar Manjeswaram 74 Kasaragod Morgal Madhur 145.2 Kasaragod Nileswar Erikkulam 127.4 Kasaragod Shiriya Paika 137 Kasaragod Uppala Uppala 90.5 -

Communicating Environmental Values in the Seventh-Day Adventist Churches in Korea

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Dissertation Projects DMin Graduate Research 2011 Toward an Eco-stewardship Ministry: Communicating Environmental Values in the Seventh-day Adventist Churches in Korea Young Seok Cha Andrews University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dmin Part of the Practical Theology Commons Recommended Citation Cha, Young Seok, "Toward an Eco-stewardship Ministry: Communicating Environmental Values in the Seventh-day Adventist Churches in Korea" (2011). Dissertation Projects DMin. 454. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dmin/454 This Project Report is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertation Projects DMin by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT TOWARD AN ECO-STEWARDSHIP MINISTRY: COMMUNICATING ENVIRONMENTAL VALUES IN THE SEVENTH- DAY ADVENTIST CHURCHES IN KOREA by Young Seok Cha Adviser: Jeanette Bryson ( \ ( ABSTRACT OF GRADUATE STUDENT RESEARCH Dissertation Andrews University Seventh-day Adventist Theological Seminary Title: TOWARD AN ECO-STEWARDSHIP MINISTRY: COMMUNICATING ENVIRONMENTAL VALUES IN THE SEVENTH-DAY ADVENTIST CHURCHES IN KOREA Name of Researcher: Young Seok Cha Name and degree of faculty adviser: Jeanette Bryson, Ph.D. Date completed: February 2011 Purpose The purpose of this project is to develop a theoretical and practical framework for implementing a ministry of ecological stewardship for Seventh-day Adventist churches in Korea and ultimately to cultivate an environmental consciousness among Adventists. In order to identify the dynamic relationships of factors involved in eco-stewardship ministry, the study first examined the environmental consciousness and practice of the pastors and members of the Seventh-day Adventist church in Korea. -

The Highlands Grapevine

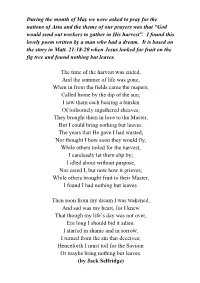

During the month of May we were asked to pray for the nations of Asia and the theme of our prayers was that “God would send out workers to gather in His harvest”. I found this lovely poem written by a man who had a dream. It is based on the story in Matt. 21:18-20 when Jesus looked for fruit on the fig tree and found nothing but leaves. The time of the harvest was ended, And the summer of life was gone, When in from the fields came the reapers, Called home by the dip of the sun; I saw them each bearing a burden Of toilsomely ingathered sheaves; They brought them in love to the Master, But I could bring nothing but leaves. The years that He gave I had wasted, Nor thought I how soon they would fly, While others toiled for the harvest, I carelessly let them slip by; I idled about without purpose, Nor cared I, but now how it grieves; While others brought fruit to their Master, I found I had nothing but leaves. Then soon from my dream I was wakened, And sad was my heart, for I knew That though my life’s day was not over, Ere long I should bid it adieu. I started in shame and in sorrow, I turned from the sin that deceives; Henceforth I must toil for the Saviour Or maybe bring nothing but leaves. (by Jack Selfridge) On the Sunday after Easter, Pete told us all about ‘Doubting Thomas’. I found myself wondering what happened to Thomas. -

Beyond Stewardship: Toward an Agapeic Environmental Ethic

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette Dissertations, Theses, and Professional Dissertations (1934 -) Projects Beyond Stewardship: Toward an Agapeic Environmental Ethic Christopher J. Vena Marquette University Follow this and additional works at: https://epublications.marquette.edu/dissertations_mu Part of the Ethics in Religion Commons, Philosophy Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Vena, Christopher J., "Beyond Stewardship: Toward an Agapeic Environmental Ethic" (2009). Dissertations (1934 -). 16. https://epublications.marquette.edu/dissertations_mu/16 BEYOND STEWARDSHIP: TOWARD AN AGAPEIC ENVIRONMENTAL ETHIC by Christopher J. Vena, B.A., M.A. A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School, Marquette University, in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Milwaukee, Wisconsin December 2009 ABSTRACT BEYOND STEWARDSHIP: TOWARD AN AGAPEIC ENVIRONMENTAL ETHIC Christopher J. Vena, B.A., M.A. Marquette University, 2009 One of the unfortunate implications of industrialization and the rapid expansion of global commerce is the magnification of the impact that humans have on their environment. Exponential population growth, along with growing technological capabilities, has allowed human societies to alter their terrain in unprecedented and destructive ways. The cumulative effect has been significant to the point that the blame for widespread environmental degradation must be pinned squarely on human shoulders. Because of our dependence on these systems for survival, the threat to the environment is a threat to human life. The root of the ecological crisis is found in human attitudes and behaviors. In the late 1960’s it was suggested that Christianity was a key source of the problem because it promoted the idea of human “dominion” over creation. -

India Nation Action Programme to Combat Desertification

lR;eso t;rs INDIA NATION ACTION PROGRAMME TO COMBAT DESERTIFICATION In the Context of UNITED NATIONS CONVENTION TO COMBAT DESERTIFICATION (UNCCD) Volume-I Status of Desertification MINISTRY OF ENVIRONMENT & FORESTS GOVERNMENT OF INDIA NEW DELHI September 2001 National Action Programme to Combat Desertification FOREWORD India is endowed with a wide variety of climate, ecological regions, land and water resources. However, with barely 2.4% of the total land area of the world, our country has to be support 16.7% of the total human population and about 18% of the total livestock population of the world. This has put enormous pressure on our natural resources. Ecosystems are highly complex systems relating to a number of factors -both biotic and abiotic - governing them. Natural ecosystems by and large have a high resilience for stability and regeneration. However, continued interference and relentless pressures on utilisation of resources leads to an upset of this balance. If these issues are not effectively and adequately addressed in a holistic manner, they can lead to major environmental problems such as depletion of vegetative cover, increase in soil ero- sion, decline in water table, and loss of biodiversity all of which directly impact our very survival. Thus, measures for conservation of soil and other natural resources, watershed development and efficient water management are the key to sustainable development of the country. The socio-ecomonic aspects of human activities form an important dimension to the issue of conservation and protection of natural resources. The measures should not only include rehabilitation of degraded lands but to also ensure that the living condi- tions of the local communities are improved.