The Citizens' Charter for Action on Drought in Kenya

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Interruption of Electricity Supply

Interruption of PARTS OF UASIN GISHU COUNTY AREA: WHOLE OF ELDORET TOWN Electricity Supply DATE: Sunday 05.09.2021 TIME: 7.00 A.M. – 5.00 P.M. Notice is hereby given under Rule 27 of the Electric Power Rules Whole of Eldoret Town, Eldoret Airport, Elgon View, MTRH, Eldoret Hosp, That the electricity supply will be interrupted as here under: KCC, St. Luke Hosp, Kapseret, Langas, Hill Sch, Eldoret Polytechnic, CUEA (It is necessary to interrupt supply periodically in order to facilitate Gaba Campus, Outspan, Elgon View, Chinese, Racecourse, Yamumbi, maintenance and upgrade of power lines to the network; to connect new Annex, West Indies, Pioneer, Kipkaren, Kamukunji, Huruma, Eldoret KCC, customers or to replace power lines during road construction, etc.) MTRH, Mediheal, St. Luke’s Hosp, Kahoya, Moi Girls High Sch, Maili Nne, Moi Baracks, Jua Kali, Turbo, Sugoi, Likuyani, Soy, Lumakanda, Kipkaren NAIROBI REGION River, Mwamba, Nangili, Ziwa, Kabenes, Kabomoi, Barsombe, Kiplombe, Maji Mazuri Flowers, Moiben, Chebororwa, Garage, Turbo Burnt Forest, AREA: PART OF PARKLANDS Cheptiret, Moi Univ, Ngeria Girls, Tulwet, Kipkabus, Flax, Sisibo T/Fact, DATE: Sunday 05.09.2021 TIME: 9.00 A.M. – 5.00 P.M. Sosiani Flowers, Wonifer, Strawberg, Naiberi, Kaiboi, Chepterwai, Kabiyet, Part of Limuru Rd, Part of 2nd, 3rd, 4th & 5th Parklands, Mtama Rd, Iregi Rd, 6th Kapsoya, Munyaka, Kipkorogot, Tugen Est, Chepkoilel, Merewet, Kuinet, Parklands, Agakhan Hosp & adjacent customers. Kimumu, Jamii Millers, Moiben, Savana Saw mill & adjacent customers. AREA: PART OF KAREN DATE: Tuesday 07.09.2021 TIME: 9.00 A.M. – 5.00 P.M. PARTS OF ELGEYO MARAKWET COUNTY Karen Country Club, DOD Karen Rd, Part of Karen Rd, Kibo Lane, Quarry AREA: ITEN, KAPSOWAR Lane, Maasai West Rd, Maasai Rd, Ushirika Rd, Koitobos Rd, Hardy, Twiga DATE: Sunday 05.09.2021 TIME: 7.00 A.M. -

Out Patient Facilities for Nhif Supa Cover Baringo County Bomet County Bungoma County Busia County

OUT PATIENT FACILITIES FOR NHIF SUPA COVER BARINGO COUNTY BRANCH No HOSPITAL NAME POSTAL ADDRESS OFFICE 1 TIONYBEI MEDICAL CLINIC 396-30400, KABARNET KABARNET 2 BARINGO DISTRICT HOSPITAL (KABARNET) 21-30400, KABARNET KABARNET 3 REALE MEDICAL CENTRE-KABARNET 4694-30100, ELDORET KABARNET 4 KERIO HOSPITAL LTD 458-30400, KABARNET KABARNET 5 RAVINE GLORY HEALTH CARE SERVICES 612-20103, ELDAMA RAVINE KABARNET 6 ELDAMA RAVINE NURSING HOME 612-20103, ELDAMA RAVINE KABARNET 7 BARNET MEMORIAL MEDICAL CENTRE 490-30400, KABARNET KABARNET BOMET COUNTY BRANCH No HOSPITAL NAME POSTAL ADDRESS OFFICE 1 CHELYMO MEDICAL CENTRE 37-20422 SILIBWET BOMET 2 KAPKOROS HEALTH CENTRE 20400 BOMET BOMET BUNGOMA COUNTY BRANCH No HOSPITAL NAME POSTAL ADDRESS OFFICE 1 CHWELE SUBCOUNTY HOSPITAL 202 - 50202 CHWELE BUNGOMA 2 LUMBOKA MEDICAL SERVICES 1883 - 50200 BUNGOMA BUNGOMA 3 WEBUYE HEALTH CENTRE 25 - WEBUYE BUNGOMA 4 ST JAMES OPTICALS 2141 50200 BUNGOMA 5 NZOIA MEDICAL CENTRE 471 - 50200 BUNGOMA BUNGOMA 6 TRINITY OPTICALS LIMITED PRIVATE BAG BUNGOMA BUNGOMA 7 KHALABA MEDICAL SERVICES 2211- 50200 BUNGOMA BUNGOMA 8 ARARAT MEDICAL CLINIC 332 KIMILILI BUNGOMA 9 SIRISIA SUBDISTRICT HOSPITAL 122 - 50208 SIRISIA BUNGOMA 10 NZOIA MEDICAL CENTRE - CHWELE 471 - 50200 BUNGOMA BUNGOMA 11 OPEN HEART MEDICAL CENTRE 388 - 50202 CHWELE BUNGOMA 12 ICFEM DREAMLAND MISSION HOSPITAL PRIVATE BAG KIMILILI BUNGOMA 13 EMMANUEL MISSION HEALTH CENTRE 53 - 50207 MISIKHU BUNGOMA 14 WEBUYE DISTRICT HOSPITAL 25 - 50205 BUNGOMA 15 ELGON VIEW MEDICAL COTTAGE 1747 - 50200 BUNGOMA BUNGOMA 16 FRIENDS -

THE KENYA GAZETTE Published by Authorrty of the Repubhc of Kenya

SPECIAL ISSUE THE KENYA GAZETTE Published by Authorrty of the Repubhc of Kenya (Registered as a Newspaper at the G P 0 ) Vol. LXIX-No 34 NAIROBI, 4th July 1967 Price Sh 1/50 CONTENTS The National Assembly Elections (Registration of Voters) Regulations 1964 and The Local Government Elections Rules 1966-Notices to Electors 704 SUPPLEMENT No. 52 Bzlls 1967 (Published as a Special Issue on 3rd July 1967) SUPPLEMENT No 53 Acts 1967 SUPPLEMENT No 54 Acts 1967 ' 704 TH F, K EN YA G AZET TE 4th July 1967 GAZETTE N OTTCE N O 2420 - --- Regtstratton Umt No Place of Regkstratton TH E N ATION AL ASSEM BLY ELECTION S (REGISTRATION OF VOTERS) REGULATION S 1964 (L N 56 of 1964) NYBRI DISTRICT Kam u 364 Oë ce of the Dlstrlct Oflicer, THE LOCAL GOVERN M EN T ELECTION S RU LES 1966 M athlra (L N 101 o! 1966) Gatundu 365 ,, N Chehe (lncludlng Cheho 366 ,, olqcs To El-Bc'roits Forest Statlon) NOTICE ls heleby gwen that lt ls proposed to com plle new KaD yu 367 , reglsters of electors for the purpose of the electlon of m em bers GR atgealt l 3698 ,, to- G athelm 370 ,, ,, (aj the Natlonal Assembly, Oalkuyu CTA'' 371 > (b) Local Authontles G aclklwuyku $$B'' 3732 ,' , A1l persons who wlsh to be reglstered as electols for the Barlcho 374 ,, purpose of elther or both of these electlons, and who are lcuga 375 ,, qualé ed to be so reglstered Gakuyu 376 ,, , m ust attend personally before the K R eglstratlon Om cer or A sslstant Reglstratlon OK cer for the M abroaltglnoaln Tl ownshlp a3,7J98 ,, reglstratlon um t ln whlch they are qualé ed to be reglstered, Tjuu -

THE KENYA GAZETTE Published by Authority of the Republic of Kenya (Registered As a Newspaperat the G.P.O.)

THE KENYA GAZETTE Published by Authority of the Republic of Kenya (Registered as a Newspaperat the G.P.O.) Vol. CXVIT—No. 47 NAIROBI, 8th May, 2015 Price Sh. 60 CONTENTS GAZETTE NOTICES PAGE PAGE The Judicial Service Act— Appointment 0.0.0 1104 The Kenya National Highway Authority (KeNHa)— Public TheJudicature Act—Comgenda ..scs-mnsnwienee e vse 1104 NOWICE on ee ceeeeeeeeeene ceneeeteseesereene sens eeeeneeesaneeee 1139 The Kenya Information and Communications Act— The Companies Act —Winding-up,etc......... 1... 1139-1140 Appointment 1104 The Physical Planning Act —Completion of Part The Tax Appeals Tribunal Act—Appointments....... 1105 DevelopmentPlan... ccc. cesses: cee nesses sees 1140 . _ : : The Environmental Management and Co-ordination Act— The State Corporations Act— Revocation of Appointments 1105 Environmental Impact Assessment Study Reports....... ... 1140-1142 The Agricultural Development Corporation Act— : Revocation of Appointment ...scsmssennsinneieeeeee 1105 Disposal of Uncollected Goods wie es ceee 1142 ThePersons with Disabilities Act— Appointments... 00. 1105-1106 Loss of Policies... eo ee eeseteeeneee sees 1142-1144 County Governments Notices ..wssesnseevrsinninencinnenee 1106—1113, 1132 Change of Name...eeecn eesseseeeecenenenee ne tunensaeees 1144 The Land Registration Act—Issue of Provisional Certificates, CC veciecseccssssesscesccsssssssessssessssesscssesessssesssseeees VV3B-V27 serenerenner The Land Act— Addendum...cee eesssessseesssenesesreenssane 1127-1128 The Mining Act—Revocation of Licences ....cccuennnns 1129-1131 SUPPLEMENTNos.46 and 54 The Elections Act—Member Nominated to the Uasin National Assembly Bills, 2015 Gishu County Assembly, ete. 0.00. ee ee eee L131, 1138-1139 PAGE The East African Community Customs ManagementAct, TheInsolvency Bill, 2015 occ csssseeeesenteceees 275 2004—Appomtment and Limits of Transit Shed, Customs Areas, CC ic cccessccescssssssesescevevsssssssersesseessseeaeaeees 1138 The Companies Bull, 2015........ -

Embu County Government Finance & Economic Planning

EMBU COUNTY GOVERNMENT FINANCE & ECONOMIC PLANNING AMENDED ANNUAL DEVELOPMENT PLAN 2016/2017 UNLOCKING THE POTENTIAL FOR EQUITABLE WEALTH AND EMPLOYMENT CREATION EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The 2016/17 County Annual Development Plan is the second to be prepared by the Embu County Government. It sets out the County’s priority programmes to be implemented in the Financial Year 2016/2017 under the Medium Term Expenditure Framework. The plan covers the following broad strategic priority areas: i. Infrastructure development (Tarmacking of major roads and maintenance of feeder and access roads) ii. Investing in Agricultural transformation and food security (Modernization of agricultural farming techniques and Value addition) iii. Investing in quality, affordable and accessible health care (i.e. preventative, curative and rehabilitation health care services through modernization of Health facilities in the County). iv. Water (Provision of clean piped water for drinking as well as construction of dams and drip water systems for irrigation farming). v. Education (ECD educational infrastructure development) vi. Tourism (Opening up of a tourism circuit in Mt. Kenya region and development of infrastructure in Mwea Game Reserve) vii. Trade, Investment and Industries (Modernizing and expanding markets throughout the county and creating a conducive environment suitable for trading, investing and for industrialization). viii. Youth and Women Economic Empowerment (Installing essential skills to youth in youth polytechnic and availing interest free loan to youth and women in business or in investment ventures). In order to achieve the county government’s development agenda, the implementing departments within the County Sectors will have to allocate resources to high impact projects and programmes that will stimulate economic growth and hence contribute to sustainable socio- economic development. -

FEBRUARY 2021.Pdf

BULK CDF NAME DATE REFERENCE NAME ADMNO AMOUNT 02-02-21 1 CHQ:085979 KIAMBU BURSARY NAOMI WANGUI MUNGAI BRM/2020/92508 4,500 02-02-21 2 CHQ:085979 KIAMBU BURSARY MBURU BRIAN WAMAI BECS/2020/68069 4,500 02-02-21 3 CHQ:085979 KIAMBU BURSARY DAVID EVERLYNE NDULULU BEDA/2019/59297 4,500 02-02-21 4 CHQ:085979 KIAMBU BURSARY MORRIS NJOROGE KIGATHI DHRM/2018/27000 4,500 27/01/2021 1 CHQ:079774 KIAMBU BURSARY PETER GATERI CHEGE BIT/2018/27052 8,000 27/01/2021 2 CHQ:079774 KIAMBU BURSARY FRED MACHARIS NJAGI BCOM/2020/90515 8,000 29/01/2021 1 CHQ:079663 KIAMBU BURSARY WANJIKU DAN NGUGI BEDA/2017/78320 5,000 29/01/2021 2 CHQ:079663 KIAMBU BURSARY WAKAMAMI LAWRENCE NDUNGU BHSM/2018/86500 5,000 29/01/2021 3 CHQ:079663 KIAMBU BURSARY WAMBUI JOSEPH KAMAU BMS/2020/66768 5,000 29/01/2021 4 CHQ:079663 KIAMBU BURSARY KAMAU GRACE MUTHONI BBM/2018/85901 5,000 02-03-21 1 CHQ:005847 LAIKIPIA WEST CDF FRANCIS WAWERU DEE/2018/35803 8,000 02-03-21 2 CHQ:005847 LAIKIPIA WEST CDF IVY WAITHIRA KAMAU BSNE/2019/88395 8,000 02-05-21 1 CHQ:061509 NAROK DOMINCK YENKO BEDA/2019/88646 10,000 02-05-21 2 CHQ:061509 NAROK RAPHAEL LOIGERO BEDA/2019/89043 5,000 23/12/2020 1 CHQ:009702 LAISAMIS CDF SIMION GALDAYAN BDS/2019/51471 10,000 23/12/2020 2 CHQ:009702 LAISAMIS CDF ANTONTELLA AHATHO BAPG/2019/88196 15,000 23/12/2020 3 CHQ:009702 LAISAMIS CDF MICHAEL G EYSIMRLE BDS/2017/72958 10,000 27/01/2021 1 CHQ:008662 KIAMBU BURSARY RUTH WAITHIRA WAITHIRA BBIT/2019/87904 6,000 27/01/2021 2 CHQ:008662 KIAMBU BURSARY MWAURA PATRICK KIARIE BEDS/2017/74252 3,800 02-03-21 1 CHQ:078693 KIAMBU -

(No. 9 of 1998) APPROVAL of REBAT

662 Kenya Subsidiary Legislation, 2017 Shirazi Dispensary Vinyunduni Dispensary Vololo Dispensary Eye Facilities for Accreditation Kapsabet Eye Care Trinity Opticals Limited Radiology Facilities for Accreditation Plasma Medical Clinic Limited West Kenya Diagnostic and Imaging Centre Dental Facilities for Accreditation Aquadent Company Limited Dental access Nairobi Clinic Dentosense Dental Clinic Eden Dental Clinic Narok Eldoret Dental Centre Empire Dental Clinic Gulumse Dental Centre Nomad Dental Centre The Eastern Dental Practice Tora Dental Clinic Ultimate Dental Centre GEOFFREY G MWANGI, Chief Executive Officer, National Hospital Insurance Fund. MOHAMUD MOHAMED ALI, Chairman, National Hospital Insurance Fund. LEGAL NOTICE No. 97 THE NATIONAL HOSPITAL INSURANCE FUND ACT (No. 9 of 1998) APPROVAL OF REBATES IN EXERCISE of the powers conferred by section 27 of the National Hospital Insurance Fund Act, the National Hospital Insurance Fund Board of Management, in consultation with the Cabinet Secretary for Health, has approved the rebates for the following hospitals for purposes of the Act— Facility Postal Address Location Contracts Option Rebate in KSh. A B C Afya International Hospital 5531-80200 Malindi 1800 Malindi Aljezeera Hospital 1016 Garissa Garissa 1600 Kenya Subsidiary Legislation, 2017 663 Facility Postal Address Location Contracts Option Rebate in KSh. A B C Athi Complex Galaxy Hospital 626, Nairobi Korrompoi 2000 Estate Balambala Sub-County Hospital 256, Garissa Balambala 1600 Al Manar Nursing Home Mandera Mandera 1800 Baraka -

Wango Road, Maintenance of Gategi Market Road

County Government of Embu |Page | 1 REPUBLIC OF KENYA EMBU COUNTY GOVERNMENT PROJECT NAME: 1. MAINTENANCE OF KARABA - WANGO ROAD 2. MAINTENANCE OF GATEGI MARKET ROADS TENDER NO: EBU/CNT/Q/254/2018-2019 THIS PROJECT IS RESERVED FOR AGPO MWEA WARD County Government of Embu |Page | 2 TABLEOFCONTENTS SECTIONI INVITATIONFORTENDERS…………………………… SECTIONII INSTRUCTIONSTOTENDERERS…………………… SECTIONIII CONDITIONSOFCONTRACT………………………… APPENDIXTOCONDITIONSOFCONTRACT……… SECTIONIV STANDARDFORMS……………………………………… SECTIONV SPECIFICATIONS, DRAWINGSAND BILLSOFQUANTITIES/SCHEDULEOFRATES… County Government of Embu |Page | 3 SECTIONI INVITATION FOR TENDERS REPUBLIC OF KENYA EMBU COUNTY GOVERNMENT Tender reference no. : EBU/CNT/Q/254/2018-2019 1.1 The County Government of Embu invites sealed tenders for PROJECT NAME: MAINTENANCE OF KARABA - WANGO ROAD, MAINTENANCE OF GATEGI MARKET ROAD 1.2 Interested eligible candidates may obtain further information and inspect Tender documents at our website: www.embu.go.ke. For more information/clarification interested applicants can visit the office of the Director of Supply Chain Management Office, during normal working hours. 1.4 Prices quoted should be net inclusive of all taxes, must be in Kenya shillings and shall remain valid for the contract period. 1.4 Original and a copy of tender documents are to be enclosed in plain sealed envelopes marked with Tender name and reference number and deposited in the Quotation Box at the front of Procurement offices or to be addressed to The County Secretary, County Government of Embu P.O. Box 36 EMBU so as to be received on or before 25TH APRIL 2019 at 11.00 am. 1.6 Tenders will be opened immediately thereafter in the presence of the candidates or their representatives who choose to attend at a location as will be designated. -

Eastern Province

EASTERN PROVINCE Eastern Province (PRE) Trunk Roads ABC Road Description Budget PRE Routine Maintenance of Bridges 7,928,125 PRE Operations of Provincial Resealing Unit 8,052,563 PRE Operation of Office 3,000,000 Meru Central/HQs Operations of Resealing Unit XII (Gakoromone) 4,239,000 C91 DB Meru - Maua 2,343,608 Machakos/HQs Operations of Resealing Unit III (Sultan Hamud) 4,266,000 Eastern (PRE) total 29,829,295 EMBU Trunk Roads ABC Road Description Budget B7 Embu - DB Mbeere 1,606,319 SUB TOTAL 1,606,319 District Roads DRE Embu Distict E629 MUGOYA -KIVWE 7,295,160.00 E652 Kanyuambora-kathageri 18,820,000.00 R0000 Administration Exp. 588,108.00 R0000 STORE 500,000.00 Total . forDRE Embu Distict 27,203,268.00 Constituency Roads Embu DRC HQ R0000 Administration/General Exp. 2,000,000.00 R0000 STORES 720,000.00 Total for Embu DRC HQ 2,720,000.00 Manyatta Const D459 DIST. BOUNDARY - E635 KAIRURI 3,575.00 D469 B7 MUTHATARI-KIAMURINGA 702,000.00 E629 Mugoya-Kivwe 2,004,000.00 E630 B6 Ena-B6(Nrb-Embu-Kivue) 1,536,200.00 E632 EMBU-KIBUGU 495,000.00 E633 Jnt.E632-D467 Kirigi 988,000.00 E634 kirigi-muruatetu 996,000.00 E635 KARURINA - KANGARU 1,001,000.00 E636 Manyatta-E647 Makengi 995,000.00 E637 MBUVORI-FOREST GATE 526,000.00 E638 Kairuri-kiriari-Kithunguriri 500,000.00 E639 mbuvori-kathuniri 502,400.00 E647 B6-Kivwe-Mirundi 1,053,000.00 E660 Kiriari-Mbuvori 700,000.00 UPP1 karurina-kithimu 1,000,000.00 UPP15 ITABUA-GATONDO 600,000.00 UPP2 MUGOYA-ITABUA-KIMANGARU 1,504,000.00 UUA1 B7 Embu-Cereal Board-GTI 637,000.00 UUF3 GAKWEGORI-KAPINGAZI-THAMBO -

Central Province (PRE) Trunk Roads ABC Road Description Budget Nyeri Hqs Operations of Resealing Unit Nyeri 4,495,000 Rmtce

NYERI PROVINCE Central Province (PRE) Trunk roads ABC Road Description Budget Nyeri HQs Operations of Resealing Unit Nyeri 4,495,000 Rmtce. Bridges 6,527,313 B5 Nyeri Nyahururu 250,000,000 Kiambu/HQs Operations of Resealing Unit II (Ngubi) 4,266,000 C65 Ruiru - Githunguri - Uplands 22,008,904 A2 Sagana River - Sagana Town 3,926,212 Kirinyaga/HQs Operations of Resealing Unit VII (Sagana) 4,239,000 A2 Thika - Makutano 2,632,222 A2 Thika - Makutano - Sagana 50,000,000 C66 Thika - A104 Flyover 26,709,299 RM C41Central Running Of Bridges Unit 2,100,000 RM Rmtce. Bridges 7,373,167 RM Central Operations of office 10,811,520 RM Central Operation of RM Office 6,527,314 Central Province (PRE) total 401,615,951 KIAMBU WEST Disrict Roads DRE Kiambu West Dist D378 WANGIGE-NYATHUNA 6,027,500.00 D402 KIMENDE-KAGWE 6,045,111.00 D407 LIMURU-KENTIMERE 6,160,120.00 R0000 administrative/Gen.exp 759,697.00 Total . forDRE Kiambu West Dist 18,992,428.00 Constituency Roads Kiambu West DRC HQ R0000 Administration/General Exp. 3,570,000.00 Total for Kiambu West DRC HQ 3,570,000.00 Lari Const D401 Nyanduma-Kariguini 214,740.00 D405 magomano-kamuchege 630,000.00 E1504 kirasha-sulmac maternity 1,002,000.00 E1524 kagaa-iria-ini-kiambaa 621,000.00 E438 githiongo-kamuchege 685,750.00 E439 ruiru river-githirioni 750,000.00 E440 Githirioni-Kagaa 254,250.00 E442 nyambari-gitithia-matathia 794,250.00 E443 gitithia-kimende 586,000.00 G10 Rukuma-Chief's Camp 600,000.00 T3216 LARI-D402 KAMAINDU 640,010.00 UC TURUTHI ROADS 978,000.00 URA11 gatiru-lari pry sch 600,000.00 URA13 -

Interruption of Electricity Supply

Interruption of AREA: KIHINGO, MAUCHE DATE: Wednesday 24.04.2019 TIME: 8.30 A.M. – 5.00 P.M. Fontana Flowers, Njoro Canners, Kenyatta Institute, Ndeffo T/Centre, Tabul Electricity Supply Dairies, Bagaria, Teret, Pwani, Naishi, Egerton Mortuary, Mauche, Store Notice is hereby given under rule 27 of the Electric Power Rules Mbili, Sopa Lodge & adjacent customers. That the electricity supply will be interrupted as here under: (It is necessary to interrupt supply periodically in order to facilitate AREA: OLENGURUONE, MOLO maintenance and upgrade of power lines to the network; to connect new Date. Friday 26.04.2019 TIME: 9.00 A.M. - 5.00 P.M. customers or to replace power lines during road construction, etc.) Whole of Olenguruone Town, Kiptagich T/Fact, Tachasis T/Fact, KTDA, Keringet Town, Tendwet, Olposimoru, Amalo, Isinya Roses & adjacent customers. NAIROBI NORTH REGION AREA: KAYOLE, KINUNGI NAIROBI COUNTY DATE: Thursday 25 .04.2019 TIME: 8.30 A.M. - 5.00 P.M. Kayole, Duka Moja, Signature, Panda Housing, Karai, 2K, Ushers Gate, Laini, AREA: WESTLANDS Nyamathi, Mwiciringiri, Nyakairu, Kinungi & adjacent customers. DATE: Wednesday 24.04.2019 TIME: 9.00 A.M. – 5.00 P.M. Part of Kolobot Rd, Part of Mushembi Rd, Kipkabus Rd, Part of Ngara Rd, AREA: KARAGITA, VILLA VIEW, MIRERA Chemelil Rd, Kenyatta University Parklands Campus, Museum Hill, Part of DATE: Friday 26.04.2019 TIME: 8.30 A.M. - 5.00 P.M. Westlands Rd, Stanchart HQtrs, Part of Chiromo Drive, International Casino Karagita Centre, Enashipai, Masada, Country Club, Lake Naivasha Resort, & adjacent customers. Sweet Lake Hotel, Villa View Est, Mirera Water Project, Mbegu Farm, Wild Fire Farm, Musaka, Tharau, Mirera, Maruti Stage & adjacent customers. -

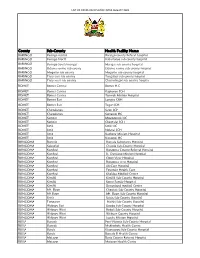

List of Covid-Vaccination Sites August 2021

LIST OF COVID-VACCINATION SITES AUGUST 2021 County Sub-County Health Facility Name BARINGO Baringo central Baringo county Referat hospital BARINGO Baringo North Kabartonjo sub county hospital BARINGO Baringo South/marigat Marigat sub county hospital BARINGO Eldama ravine sub county Eldama ravine sub county hospital BARINGO Mogotio sub county Mogotio sub county hospital BARINGO Tiaty east sub county Tangulbei sub county hospital BARINGO Tiaty west sub county Chemolingot sub county hospital BOMET Bomet Central Bomet H.C BOMET Bomet Central Kapkoros SCH BOMET Bomet Central Tenwek Mission Hospital BOMET Bomet East Longisa CRH BOMET Bomet East Tegat SCH BOMET Chepalungu Sigor SCH BOMET Chepalungu Siongiroi HC BOMET Konoin Mogogosiek HC BOMET Konoin Cheptalal SCH BOMET Sotik Sotik HC BOMET Sotik Ndanai SCH BOMET Sotik Kaplong Mission Hospital BOMET Sotik Kipsonoi HC BUNGOMA Bumula Bumula Subcounty Hospital BUNGOMA Kabuchai Chwele Sub-County Hospital BUNGOMA Kanduyi Bungoma County Referral Hospital BUNGOMA Kanduyi St. Damiano Mission Hospital BUNGOMA Kanduyi Elgon View Hospital BUNGOMA Kanduyi Bungoma west Hospital BUNGOMA Kanduyi LifeCare Hospital BUNGOMA Kanduyi Fountain Health Care BUNGOMA Kanduyi Khalaba Medical Centre BUNGOMA Kimilili Kimilili Sub-County Hospital BUNGOMA Kimilili Korry Family Hospital BUNGOMA Kimilili Dreamland medical Centre BUNGOMA Mt. Elgon Cheptais Sub-County Hospital BUNGOMA Mt.Elgon Mt. Elgon Sub-County Hospital BUNGOMA Sirisia Sirisia Sub-County Hospital BUNGOMA Tongaren Naitiri Sub-County Hospital BUNGOMA Webuye