Palbociclib (PD-0332991), a Selective CDK4/6 Inhibitor, Restricts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Proteomics and Drug Repurposing in CLL Towards Precision Medicine

cancers Review Proteomics and Drug Repurposing in CLL towards Precision Medicine Dimitra Mavridou 1,2,3, Konstantina Psatha 1,2,3,4,* and Michalis Aivaliotis 1,2,3,4,* 1 Laboratory of Biochemistry, School of Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, GR-54124 Thessaloniki, Greece; [email protected] 2 Functional Proteomics and Systems Biology (FunPATh)—Center for Interdisciplinary Research and Innovation (CIRI-AUTH), GR-57001 Thessaloniki, Greece 3 Basic and Translational Research Unit, Special Unit for Biomedical Research and Education, School of Medicine, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, GR-54124 Thessaloniki, Greece 4 Institute of Molecular Biology and Biotechnology, Foundation of Research and Technology, GR-70013 Heraklion, Greece * Correspondence: [email protected] (K.P.); [email protected] (M.A.) Simple Summary: Despite continued efforts, the current status of knowledge in CLL molecular pathobiology, diagnosis, prognosis and treatment remains elusive and imprecise. Proteomics ap- proaches combined with advanced bioinformatics and drug repurposing promise to shed light on the complex proteome heterogeneity of CLL patients and mitigate, improve, or even eliminate the knowledge stagnation. In relation to this concept, this review presents a brief overview of all the available proteomics and drug repurposing studies in CLL and suggests the way such studies can be exploited to find effective therapeutic options combined with drug repurposing strategies to adopt and accost a more “precision medicine” spectrum. Citation: Mavridou, D.; Psatha, K.; Abstract: CLL is a hematological malignancy considered as the most frequent lymphoproliferative Aivaliotis, M. Proteomics and Drug disease in the western world. It is characterized by high molecular heterogeneity and despite the Repurposing in CLL towards available therapeutic options, there are many patient subgroups showing the insufficient effectiveness Precision Medicine. -

The Ongoing Search for Biomarkers of CDK4/6 Inhibitor Responsiveness in Breast Cancer Scott F

MOLECULAR CANCER THERAPEUTICS | REVIEW The Ongoing Search for Biomarkers of CDK4/6 Inhibitor Responsiveness in Breast Cancer Scott F. Schoninger1 and Stacy W. Blain2 ABSTRACT ◥ CDK4 inhibitors (CDK4/6i), such as palbociclib, ribociclib, benefit from these agents, often switching to chemotherapy and abemaciclib, are approved in combination with hormonal within 6 months. Some patients initially benefit from treatment, therapy as a front-line treatment for metastatic HRþ,HER2- but later develop secondary resistance. This highlights the need breast cancer. Their targets, CDK4 and CDK6, are cell-cycle for complementary or companion diagnostics to pinpoint – regulatory proteins governing the G1 S phase transition across patients who would respond. In addition, because CDK4 is a many tissue types. A key challenge remains to uncover biomar- bona fide target in other tumor types where CDK4/6i therapy is kers to identify those patients that may benefit from this class of currently in clinical trials, the lack of target identification may drugs. Although CDK4/6i addition to estrogen modulation ther- obscure benefit to a subset of patients there as well. This review apy essentially doubles the median progression-free survival, summarizes the current status of CDK4/6i biomarker test devel- overall survival is not significantly increased. However, in reality opment, both in clinical trials and at the bench, with particular only a subset of treated patients respond. Many patients exhibit attention paid to those which have a strong biological basis as primary resistance to CDK4/6 inhibition and do not derive any well as supportive clinical data. Introduction well (7). Although these results are promising, the clinical use of CDK4/6 inhibitors is confounded by the high individual variability in Breast cancer is the most common women's cancer worldwide, clinical response. -

RB1 Dual Role in Proliferation and Apoptosis: Cell Fate Control and Implications for Cancer Therapy

www.impactjournals.com/oncotarget/ Oncotarget, Vol. 6, No. 20 RB1 dual role in proliferation and apoptosis: Cell fate control and implications for cancer therapy Paola Indovina1,2, Francesca Pentimalli3, Nadia Casini2, Immacolata Vocca3, Antonio Giordano1,2 1Sbarro Institute for Cancer Research and Molecular Medicine, Center for Biotechnology, College of Science and Technology, Temple University, Philadelphia, PA, USA 2 Department of Medicine, Surgery and Neuroscience, University of Siena and Istituto Toscano Tumori (ITT), Siena, Italy 3Oncology Research Center of Mercogliano (CROM), Istituto Nazionale Tumori “Fodazione G. Pascale” – IRCCS, Naples, Italy Correspondence to: Antonio Giordano, e-mail: [email protected] Keywords: RB family, apoptosis, E2F, cancer therapy, CDK inhibitors Received: May 14, 2015 Accepted: June 06, 2015 Published: June 18, 2015 ABSTRACT Inactivation of the retinoblastoma (RB1) tumor suppressor is one of the most frequent and early recognized molecular hallmarks of cancer. RB1, although mainly studied for its role in the regulation of cell cycle, emerged as a key regulator of many biological processes. Among these, RB1 has been implicated in the regulation of apoptosis, the alteration of which underlies both cancer development and resistance to therapy. RB1 role in apoptosis, however, is still controversial because, depending on the context, the apoptotic cues, and its own status, RB1 can act either by inhibiting or promoting apoptosis. Moreover, the mechanisms whereby RB1 controls both proliferation and apoptosis in a coordinated manner are only now beginning to be unraveled. Here, by reviewing the main studies assessing the effect of RB1 status and modulation on these processes, we provide an overview of the possible underlying molecular mechanisms whereby RB1, and its family members, dictate cell fate in various contexts. -

Palbociclib for Male Patients with Metastatic Breast Cancer

Author Manuscript Published OnlineFirst on October 24, 2019; DOI: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-2580 Author manuscripts have been peer reviewed and accepted for publication but have not yet been edited. CCR-19-2580 Title: FDA Approval Summary: Palbociclib for Male Patients with Metastatic Breast Cancer Authors: Suparna Wedam1*, Lola Fashoyin-Aje1*, Erik Bloomquist1, Shenghui Tang1, Rajeshwari Sridhara1, Kirsten B. Goldberg2, Marc R. Theoret1, Laleh Amiri-Kordestani1, Richard Pazdur1,2, Julia A. Beaver1 Authors’ Affiliation: 1Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, U.S. Food and Drug Administration; 2Oncology Center of Excellence, U.S. Food and Drug Administration Running Title: FDA Approval of Palbociclib for Male Breast Cancer Corresponding Author: Suparna Wedam, Office of Hematology and Oncology Products, CDER, U.S. Food and Drug Administration, WO22 Room 2112, 10903 New Hampshire Avenue, Silver Spring, MD 20993. Phone: 301-796-1776 Fax: 301-796-9909. Email: [email protected] *: SW and LF-A contributed equally to this publication. Note: This is a U.S. Government work. There are no restrictions on its use. Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest: The authors report no financial interests or relationships with the commercial sponsors of any products discussed in this report. Word count: Abstract, 187. Text: 2836. Tables: 1. Figures: 1. References: 17 1 Downloaded from clincancerres.aacrjournals.org on September 27, 2021. © 2019 American Association for Cancer Research. Author Manuscript Published OnlineFirst on October 24, 2019; DOI: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-2580 Author manuscripts have been peer reviewed and accepted for publication but have not yet been edited. Abstract On April 4, 2019, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved a supplemental new drug application for palbociclib (IBRANCE®), to expand the approved indications in women with hormone receptor (HR)-positive, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-negative advanced or metastatic breast cancer (MBC) in combination with an aromatase inhibitor or fulvestrant, to include men. -

A Phase II Single Arm Study of Palbociclib in Patients with Metastatic HER2-Positive Breast Cancer with Brain Metastasis

IRB #: STU00202582-CR0003 Approved by NU IRB for use on or after 1/28/2019 through 1/27/2020. A Phase II Single Arm Study of Palbociclib in Patients with Metastatic HER2-positive Breast Cancer with Brain Metastasis Principal Investigator: Massimo Cristofanilli, MD Professor of Medicine Associate Director of Translational Research and Precision Medicine Department of Medicine-Hematology and Oncology Robert H Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center Feinberg School of Medicine 710 N Fairbanks Court, Olson Building, Suite 8-250A Chicago, IL 60611 Tel: 312-503-5488 Email: [email protected] NU Sub-Investigator(s): Northwestern University Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center Priya Kumthekar, MD Jonathan Strauss Luis Blanco Sofia Garcia Northwestern Lake Forest Hospital Valerie Nelson, MD Affiliate Site PIs: Jenny Chang, MD Houston Methodist Hospital/Houston Methodist Cancer Center 6445 Main Street, P24-326 Houston, Texas 77030 Tel: 713-441-9948 [email protected] Biostatistician: Alfred Rademaker [email protected] Study Intervention(s): Palbociclib (Ibrance) IND Number: Exempt IND Holder: N/A Funding Source: Pfizer Version Date: August 15, 2017 (Amendment 5) Coordinating Center: Clinical Research Office Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center Northwestern University 676 N. St. Clair, Suite 1200 Chicago, IL 60611 http://cancer.northwestern.edu/CRO/index.cfm 1 Version :08.15.2017 IRB #: STU00202582-CR0003 Approved by NU IRB for use on or after 1/28/2019 through 1/27/2020. Table of Contents STUDY SCHEMA ........................................................................................................................... -

Palbociclib Capsules PALBACE®

For the use only of Registered Medical Practitioner (Oncologist) or a Hospital or a Laboratory. Palbociclib Capsules PALBACE® 1. GENERIC NAME Palbociclib 2. QUALITATIVE AND QUANTITATIVE COMPOSITION Each hard capsule contains 75 mg, 100 mg and 125 mg of Palbociclib. List of excipients: Microcrystalline cellulose, lactose monohydrate, sodium starch glycolate, colloidal silicon dioxide, magnesium stearate, and hard gelatin capsule shells. The light orange, light orange/caramel and caramel opaque capsule shells contain gelatin, red iron oxide, yellow iron oxide, and titanium dioxide; and the printing ink contains shellac, titanium dioxide, ammonium hydroxide, propylene glycol and simethicone. All strengths/presentations of this product may not be marketed. 3. DOSAGE FORM AND STRENGTH Hard gelatin capsules available in 75 mg, 100 mg and 125 mg strengths. 4. CLINICAL PARTICULARS 4.1 Therapeutic Indications For Women: Palbociclib is indicated for the treatment of hormone receptor (HR)-positive, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-negative locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer: - in combination with an aromatase inhibitor; - in combination with fulvestrant in women who have received prior endocrine therapy (see section 5.2). In pre- or perimenopausal women, the endocrine therapy should be combined with a luteinizing hormone releasing hormone (LHRH) agonist. ®Trademark Proprietor: Pfizer Inc., USA Licensed User: Pfizer Products India Private Limited, India PALBACE Capsule Page 1 of 26 LPDPAB042021 PfLEET Number: 2021-0069100; 2021-0069426 For Men: Palbociclib is indicated for the treatment of hormone receptor (HR)-positive, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-negative advanced or metastatic breast cancer in combination with: an aromatase inhibitor as initial endocrine-based therapy. -

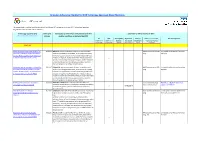

Formulary Adherence Checklist for NICE Technology Appraisals About Medicines

Formulary Adherence Checklist for NICE Technology Appraisals About Medicines This spreadsheet is updated monthly and details Pan Mersey APC adherence to current NICE Technology Appraisals. All guidelines refer to adults unless indicated. Technology appraisal (TA) Date of TA Availability of medicine for NHS patients with this Adherence of APC formulary to NICE Titles are hyperlinks to full guidance Release medical condition, as indicated by NICE Yes N/A Date of APC Implement Time to Notes (e.g. rationale, Pan Mersey Notes (mark 'x' if (mark 'x' if website by (30/90 implement method of making applicable) applicable) upload days of TA ) (days) available) 2017-18 Ribociclib with an aromatase inhibitor for 20/12/17 Ribociclib, with an aromatase inhibitor, is recommended NHSE commissioned RED Link added to Pan Mersey formulary previously untreated, hormone receptor- within its marketing authorisation, as an option for treating drug 28/12/17. positive, HER2-negative, locally advanced hormone receptor-positive, human epidermal growth factor or metastatic breast cancer [TA496] receptor 2‑negative, locally advanced or metastatic breast x cancer as initial endocrine-based therapy in adults. Ribociclib is recommended only if the company provides it with the discount agreed in the patient access scheme. Palbociclib with an aromatase inhibitor for 20/12/17 Palbociclib, with an aromatase inhibitor, is recommended NHSE commissioned RED Link added to Pan Mersey formulary previously untreated, hormone receptor- within its marketing authorisation, as an option for treating drug 28/12/17. positive, HER2-negative, locally advanced hormone receptor-positive, human epidermal growth factor or metastatic breast cancer [TA495] receptor 2-negative, locally advanced or metastatic breast x cancer as initial endocrine-based therapy in adults. -

Dual Targeting of CDK4/6 and BCL2 Pathways Augments Tumor Response in Estrogen Receptor–Positive Breast Cancer James R

Published OnlineFirst April 3, 2020; DOI: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-1872 CLINICAL CANCER RESEARCH | TRANSLATIONAL CANCER MECHANISMS AND THERAPY Dual Targeting of CDK4/6 and BCL2 Pathways Augments Tumor Response in Estrogen Receptor–Positive Breast Cancer James R. Whittle1,2,3, Francois¸ Vaillant1,3, Elliot Surgenor1, Antonia N. Policheni3,4,Goknur€ Giner3,5, Bianca D. Capaldo1,3, Huei-Rong Chen1,HeK.Liu1, Johanna F. Dekkers1,6,7, Norman Sachs6, Hans Clevers6,7, Andrew Fellowes8, Thomas Green8, Huiling Xu8, Stephen B. Fox8,9, Marco J. Herold3,10, Gordon K. Smyth5,11, Daniel H.D. Gray3,4, Jane E. Visvader1,3, and Geoffrey J. Lindeman1,2,12 ABSTRACT ◥ Purpose: Although cyclin-dependent kinase 4 and 6 (CDK4/6) Results: Triple therapy was well tolerated and produced a super- inhibitors significantly extend tumor response in patients with ior and more durable tumor response compared with single or þ metastatic estrogen receptor–positive (ER ) breast cancer, relapse doublet therapy. This was associated with marked apoptosis, includ- is almost inevitable. This may, in part, reflect the failure of CDK4/6 ing of senescent cells, indicative of senolysis. Unexpectedly, ABT- – inhibitors to induce apoptotic cell death. We therefore evaluated 199 resulted in Rb dephosphorylation and reduced G1 S cyclins, combination therapy with ABT-199 (venetoclax), a potent and most notably at high doses, thereby intensifying the fulvestrant/ selective BCL2 inhibitor. palbociclib–induced cell-cycle arrest. Interestingly, a CRISPR/Cas9 Experimental Design: BCL2 family member expression was screen suggested that ABT-199 could mitigate loss of Rb (and assessed following treatment with endocrine therapy and the potentially other mechanisms of acquired resistance) to palbociclib. -

Phenotype-Based Drug Screening Reveals Association Between Venetoclax Response and Differentiation Stage in Acute Myeloid Leukemia

Acute Myeloid Leukemia SUPPLEMENTARY APPENDIX Phenotype-based drug screening reveals association between venetoclax response and differentiation stage in acute myeloid leukemia Heikki Kuusanmäki, 1,2 Aino-Maija Leppä, 1 Petri Pölönen, 3 Mika Kontro, 2 Olli Dufva, 2 Debashish Deb, 1 Bhagwan Yadav, 2 Oscar Brück, 2 Ashwini Kumar, 1 Hele Everaus, 4 Bjørn T. Gjertsen, 5 Merja Heinäniemi, 3 Kimmo Porkka, 2 Satu Mustjoki 2,6 and Caroline A. Heckman 1 1Institute for Molecular Medicine Finland, Helsinki Institute of Life Science, University of Helsinki, Helsinki; 2Hematology Research Unit, Helsinki University Hospital Comprehensive Cancer Center, Helsinki; 3Institute of Biomedicine, School of Medicine, University of Eastern Finland, Kuopio, Finland; 4Department of Hematology and Oncology, University of Tartu, Tartu, Estonia; 5Centre for Cancer Biomarkers, De - partment of Clinical Science, University of Bergen, Bergen, Norway and 6Translational Immunology Research Program and Department of Clinical Chemistry and Hematology, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland ©2020 Ferrata Storti Foundation. This is an open-access paper. doi:10.3324/haematol. 2018.214882 Received: December 17, 2018. Accepted: July 8, 2019. Pre-published: July 11, 2019. Correspondence: CAROLINE A. HECKMAN - [email protected] HEIKKI KUUSANMÄKI - [email protected] Supplemental Material Phenotype-based drug screening reveals an association between venetoclax response and differentiation stage in acute myeloid leukemia Authors: Heikki Kuusanmäki1, 2, Aino-Maija -

Population Pharmacokinetics of Palbociclib in a Real-World Situation

pharmaceuticals Article Population Pharmacokinetics of Palbociclib in a Real-World Situation Bernard Royer 1,2,*, Courèche Kaderbhaï 3, Jean-David Fumet 3,4, Audrey Hennequin 3, Isabelle Desmoulins 3, Sylvain Ladoire 3,4, Siavoshe Ayati 3, Didier Mayeur 3, Sivia Ilie 3 and Antonin Schmitt 4,5 1 Laboratoire de Pharmacologie Clinique et Toxicologie, CHU Besançon, 25000 Besançon, France 2 INSERM, EFS BFC, UMR1098, RIGHT, Interactions Greffon-Hôte-Tumeur/Ingénierie Cellulaire et Génique, University of Bourgogne Franche-Comté, 25000 Besançon, France 3 Oncology Department, Centre Georges-François Leclerc, 21000 Dijon, France; cgkaderbhai@cgfl.fr (C.K.); jdfumet@cgfl.fr (J.-D.F.); ahennequin@cgfl.fr (A.H.); IDesmoulins@cgfl.fr (I.D.); sladoire@cgfl.fr (S.L.); sayati@cgfl.fr (S.A.); dmayeur@cgfl.fr (D.M.); silie@cgfl.fr (S.I.) 4 INSERM U1231, University of Burgundy Franche-Comté, 21000 Dijon, France; aschmitt@cgfl.fr 5 Pharmacy Department, Centre Georges-François Leclerc, 21000 Dijon, France * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Palbociclib is an oral cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor that is used in combination with aromatase inhibitors in the treatment of postmenopausal women with metastatic breast cancer. Its metabolism profile is associated with an important interpatient variability. We performed a population pharmacokinetics study of palbociclib in women routinely followed in a cancer center. One hundred and fifty-one samples were analyzed. The sampling times after administration ranged from 0.9 to 75 h and the samples were taken between 1 and 21 days after the beginning of the palbociclib cycle. Palbociclib was determined using a validated mass spectrometry method. -

Advances in the Treatment of Acute Myeloid Leukemia: New Drugs and New Challenges

Published OnlineFirst February 3, 2020; DOI: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-19-1011 REVIEW Advances in the Treatment of Acute Myeloid Leukemia: New Drugs and New Challenges Nicholas J. Short , Marina Konopleva , Tapan M. Kadia , Gautam Borthakur , Farhad Ravandi , Courtney D. DiNardo , and Naval Daver ABSTRACT The therapeutic armamentarium of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) has rapidly expanded in the past few years, driven largely by translational research into its genomic landscape and an improved understanding of mechanisms of resistance to conventional thera- pies. However, primary and secondary drug resistance remains a substantial problem for most patients. Research into the mechanisms of resistance to these new agents is informing the development of the next class of AML drugs and the design of combination regimens aimed at optimally exploiting thera- peutic vulnerabilities, with the ultimate goal of eradicating all subclones of the disease and increasing cure rates in AML. Signifi cance: AML is a heterogeneous disease, characterized by a broad spectrum of molecular altera- tions that infl uence clinical outcomes and also provide potential targets for drug development. This review discusses the current and emerging therapeutic landscape of AML, highlighting novel classes of drugs and how our expanding knowledge of mechanisms of resistance are informing future therapies and providing new opportunities for effective combination strategies. INTRODUCTION importance of the apoptotic machinery in chemotherapy resistance and AML propagation has also led to the devel- Driven by intense basic and translational research, the opment of apoptosis-inducing therapies that appear to be past 10 to 15 years have greatly improved our understanding effi cacious irrespective of the presence or absence of targeta- of the pathobiology and genetic diversity of acute myeloid ble genetic mutations ( 6, 7 ). -

And Emerging, Pivotal Signalling Pathways in Metastatic Breast Cancer

REVIEW British Journal of Cancer (2017) 116, 10–20 | doi: 10.1038/bjc.2016.405 Keywords: breast cancer; aromatase inhibitor; mTOR inhibitor; PI3K inhibitor; CDK4/6 inhibitor; anastrozole; letrozole; exemestane Cotargeting of CYP-19 (aromatase) and emerging, pivotal signalling pathways in metastatic breast cancer Stine Daldorff1, Randi Margit Ruud Mathiesen1, Olav Erich Yri1, Hilde Presterud Ødegård1 and Ju¨ rgen Geisler*,1,2 1Department of Oncology, Akershus University Hospital (AHUS), Lørenskog N-1478, Norway and 2Institute of Clinical Medicine, University of Oslo, Campus AHUS, Oslo N-0313, Norway Aromatase inhibition is one of the cornerstones of modern endocrine therapy of oestrogen receptor-positive (ER þ ) metastatic breast cancer (MBC). The nonsteroidal aromatase inhibitors anastrozole and letrozole, as well as the steroidal aromatase inactivator exemestane, are the preferred drugs and established worldwide in all clinical phases of the disease. However, although many patients suffering from MBC experience an initial stabilisation of their metastatic burden, drug resistance and disease progression occur frequently, following in general only a few months on treatment. Extensive translational research during the past two decades has elucidated the major pathways contributing to endocrine resistance and paved the way for clinical studies investigating the efficacy of novel drug combinations involving aromatase inhibitors and emerging drugable targets like mTOR, PI3K and CDK4/6. The present review summarises the basic research that