Black Artists in 1980S Britain Nottingham

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

September 2019 Diary London Museums Galleries

BLUE BADGE TATE SOUTHWARK CATHEDRAL www.tate.org.uk 020 7887 8008 (rec. info) Main 7887 8888 www.southwarkcathedral.org.uk GUIDES’ DIARY TATE BRITAIN 020 7367 6734 Permit required for photography 020 7367 6700 Daily: 10.00-18.00. Mon-Sat 0800-1800 (le1730) Sun 1100-1700 (le 1630) To: 6/10: Mike Nelson: The Asset Strippers: Free Grps 10+ special rates depending on whether guided tour required. 11/9-2/2: William Blake: The Artist:£18/£17 Grps : Ad £4.50, Conc £3.50, Ch 1-11 £2.00 Grps 020 7367 6734. SEPTEMBER 2019 24/9-5/1: Mark Leckey: O’Magic Power of Bleakness:£13/£12 Trade: Ad £3.50. Concs £3.00 Ch £1.75 (incl BBTGs – book direct) TATE MODERN Services: Mon-Sat. 0800 (0900 Sat), 0815 HC (0915 Sat), 1230, 1245HC LONDON Sun-Thur: 10.00-18.00; Fri-Sat: 10.00-22.00 1730 Choral Evensong (1600 Sat) – said Mon/Wed To:8/9: Natalia Goncharova:£16/£15 Sun 0845, 0900 HC, 1100 HC, 1500 CHoral Evensong, 1830 ‘At Southwark’ To: 27/10: Takis: £13 Suns. 1st Trad CHoral EucHarist, 2nd Service of LigHt, ART GALLERIES To 5/1: Olafur Eliasson:£18/£17 3rd Wholeness and Healing, 4th Compline/EucHaristic Devotion To:13/9: Magdalena Abkanowicz Organ recital every Mon 1300, music recital everyTues 1515 BARBICAN ART GALLERY Closures: No information available at time of going to press, check website www.barbican.org.uk 020 7638 4141 WHITECHAPEL GALLERY Sun-Wed 10.00-18.00 Thu-Sat 10.00-21.00. www.whitechapelgallery.org 7522 7888 TEMPLE CHURCH The Curve: Sat-Wed: 11.00-20.00 Thurs/Fri: 11.00-21.00 Tue-Sun 11.00-18.00; Thur 11.00-21.00; Adm Free. -

National Dimensions

ONS NATIONAL DIM NATIONAL DIMENNATIONAL DIMENSIONS NAL DIMENSIONS DIMENSIONS NATIO This report was researched and written by AEA Consulting: Magnus von Wistinghausen Keith Morgan Katharine Housden This report sets out the collaborative work undertaken by the UK’s nationally funded museums, libraries and archives with other organisations across the UK, and assesses their impact on cultural provision across the nation. It focuses on the activities in recent years of members of the National Museum Directors’ Conference (NMDC), and is largely based on discussions with these institutions and selected partner organisations, as well as on a series of discussion days hosted by the NMDC in different regional centres in July 2003. It does not make specific reference to collaborative work between NMDC organisations themselves, and focuses on activities and initiatives that have taken place in the last few years. For the sake of simplicity the term ‘national museum’ is used throughout the report to describe all NMDC member organisations, notwithstanding the fact that these also include libraries and archives. In this report the term ‘national’ is used to denote institutions established by Act of Parliament as custodians of public collections that belong to the nation. It is acknowledged that the NMDC does not include all museums and other collecting institutions which carry the term ‘national’ as part of their name. Specific reference to their activities is not contained in this report. Published in the United Kingdom by the National Museum Directors' -

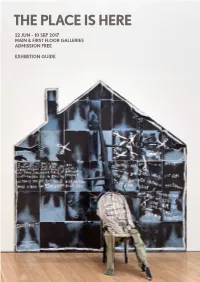

Gallery Guide Is Printed on Recycled Paper

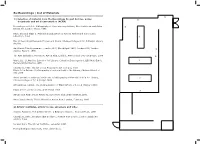

THE PLACE IS HERE 22 JUN – 10 SEP 2017 MAIN & FIRST FLOOR GALLERIES ADMISSION FREE EXHIBITION GUIDE THE PLACE IS HERE LIST OF WORKS 22 JUN – 10 SEP 2017 MAIN GALLERY The starting-point for The Place is Here is the 1980s: For many of the artists, montage allowed for identities, 1. Chila Kumari Burman blends word and image, Sari Red addresses the threat a pivotal decade for British culture and politics. Spanning histories and narratives to be dismantled and reconfigured From The Riot Series, 1982 of violence and abuse Asian women faced in 1980s Britain. painting, sculpture, photography, film and archives, according to new terms. This is visible across a range of Lithograph and photo etching on Somerset paper Sari Red refers to the blood spilt in this and other racist the exhibition brings together works by 25 artists and works, through what art historian Kobena Mercer has 78 × 190 × 3.5cm attacks as well as the red of the sari, a symbol of intimacy collectives across two venues: the South London Gallery described as ‘formal and aesthetic strategies of hybridity’. between Asian women. Militant Women, 1982 and Middlesbrough Institute of Modern Art. The questions The Place is Here is itself conceived of as a kind of montage: Lithograph and photo etching on Somerset paper it raises about identity, representation and the purpose of different voices and bodies are assembled to present a 78 × 190 × 3.5cm 4. Gavin Jantjes culture remain vital today. portrait of a period that is not tightly defined, finalised or A South African Colouring Book, 1974–75 pinned down. -

Donald Rodney (1961-1998) Self-Portrait ‘Black Men Public Enemy’ 1990

Donald Rodney (1961-1998) Self-Portrait ‘Black Men Public Enemy’ 1990 Medium: Lightboxes with Duratran prints Size: 5 parts, total, 190.5 x 121.9cm Collection: Arts Council ACC7/1990 1. Art historical terms and concepts Subject Matter Traditionally portraits depicted named individuals for purposes of commemoration and/or propaganda. In the past black figures were rarely portrayed in Western art unless within group portraits where they were often used as a visual and social foil to the main subject. Rodney adopted the portrait to explore issues around black masculine identity - in this case the stereotype of young black men as a ‘public enemy’. The title ‘Black Men Public Enemy’ comes from the writings of cultural theorist Stuart Hall about media representations of young black men as an ‘icon of danger’, a metaphor for all the ills of society. Rodney said of this Art History in Schools CIO | Registered Charity No. 1164651 | www.arthistoryinschools.org.uk work: “I’ve been working for some time on a series…about a black male image, both in the media and black self-perception. I wanted to make a self-portrait [though] I didn’t want to produce a picture with an image of myself in it. It would be far too heroic considering the subject matter. I wanted generic black men, a group of faces that represented in a stereotypical way black man as ‘the other’, a black man as the enemy within the body politic” (1991). Rodney is asking the question: ‘Is this what people see when they see me?’ He has created a kind of ‘everyman’ for every black man, a heterogeneous identity. -

Lubaina Himid OUR KISSES ARE PETALS

Media Release: 5 April 2018 PRESS PREVIEW Thursday 10 May 2018 EXHIBITION 11 May – 30 September 2018 Lubaina Himid OUR KISSES ARE PETALS Lubaina Himid, Why are you Looking, 2018. Image courtesy the artist and Hollybush Gardens BALTIC Centre for Contemporary Art will launch the first in a series of exhibitions for the UK’s largest public event of 2018, the Great Exhibition of the North (22 June – 9 September), with a solo show of new work by Turner Prize-winning artist Lubaina Himid. Our Kisses are Petals will run from 11 May – 30 September, and will feature a community-focussed outdoor commission beginning in June. Our Kisses are Petals originates from new paintings on cloth that employ the patterns, colours and symbolism of the Kanga, a vibrant cotton fabric traditionally worn by East African women as a shawl, head scarf, baby carrier, or wrapped around the waist. Typically, kangas consist of three parts: the pindo (border), the mji (central motif), and the jina (message or ‘name’), which often takes the form of a riddle or proverb. For Himid, these multicoloured fabrics are ‘speaking clothes’, which employ ‘the language of image, pattern and text through which one woman’s outfit talks to another’s’. Himid’s works engage in a dialogue with each other and with the viewer, both through their individual jina, borrowed from influential writers just as James Baldwin, Sonia Sanchez, Essex Hemphill and Audre Lorde, and through the invitation for visitors to rearrange the hanging works by a system of pulleys to form their own poetry. The suspended Kangas take on a flag-like quality, which, together with the colours and patterns of the fabrics, evoke regimental and ceremonial colonial flag-bearing. -

ART of the CARIBBEAN ‘A Wonderful Set of Images Which Helps to Re-Define the Boundaries of the Caribbean for a British Onlooker

PartGOODWILL 1 — Caribbean TEACHING art history GUIDE — the essential teaching resource for craft, design and culture LIST OF CONTENTS ART OF THE CARIBBEAN ‘A wonderful set of images which helps to re-define the boundaries of the Caribbean for a British onlooker. The visual art is supported by concise and effective background material, both historical and textual’. Dr. Paul Dash, Department of Education, Goldsmith’s College. LIST OF CONTENTS PART 3 This set explores Caribbean culture Looking at the pictures and its arresting visual art Unknown Taino Artist, Jamaica, Avian Figure Introduction Isaac Mendes Belisario, Jamaica, House John Canoe Map of the Caribbean Georges Liautaud, Haiti, Le Major Jonc Time-line Annalee Davis, Barbados, This Land of Mine: Past, Present and Future John Dunkley, Jamaica, Banana Plantation Wifredo Lam, Cuba, The Chair PART 1 Raul Martinez, Cuba, Cuba Caribbean art history Edna Manley, England/Jamaica, The Voice Colonial Cuba Unknown Djuka Artist, Suriname, Apinti Drum Cuban art since1902 Everald Brown, Jamaica, Instrument for Four People Stanley Greaves Caribbean Man No. 2 Colonial Saint-Domingue Aubrey Williams, Guyana/England, Shostakovich 3rd Symphony Cecil Baugh, Jamaica, Global Vase with Egyptian blue running glaze Haitian art since 1811 Stephanie Correia, Guyana, Tuma 1 Dutch West-Indian colonies Philip Moore, Guyana, Bat and Ball Fantasy British West Indies Ronald Moody, Jamaica/England, Midonz (Goddess of Transmutation) English-speaking Caribbean: Jamaica, Stanley Greaves, Guyana/Barbados, Caribbean Man No. 2 Barbados, Guyana, Trinidad, Wilson Bigaud, Haiti, Zombies Ras Aykem-i Ramsay, Barbados, Moses For easy navigation blue signals a link to a Caribbean-born artists in Britain Pen Cayetano, Belize, A Belizean History: Triumph of Unity relevant page. -

Lubaina Himid Invisible Strategies Exhibition Notes

2. Le Rodeur: The Lock, 2016 Revenge – A Masque in Five Tableaux 7. Fishing, 1987 9. Mr Salt’s Collection – The Ballad of 3. Le Rodeur: Exchange, 2016 4. Ankledeep, 1991 Fishing was originally part of a larger the Wing series, 1989 After completing this most recent 5. Five, 1991 installation: a cast of cutout painted This work was first shown as part characters roaming across gallery walls. of Himid’s solo exhibition The Ballad series, the artist realised that these 6. Carpet, 1992 interiors were the odd, empty rooms Collectively titled Restoring the Balance, of the Wing at Chisenhale Gallery, of her earlier Plan B paintings, now 8. Unwrapped but not Untied, 1991 these figures appeared within the London, in 1989. It displays the artist’s first retrospective exhibition influence on her practice of populated with a full cast of characters, Himid asserts: ‘After the mourning New Robes for MaShulan, a caricature, particularly eighteenth- and always with a glimpsed view of comes revenge.’ Revenge is at once collaboration with Maud Sulter held at century satirical cartoonists such the sea. They reflect Himid’s complex a monument to the victims of the Rochdale Art Gallery in 1987. In Sulter’s as James Gillray, George Cruikshank 1. Freedom and Change, 1984 personal relationship to water and the transatlantic slave trade, a critique of 10. Bone in the China: Success to the curatorial text, ‘Surveying the Scene’, and William Hogarth. The painting sea: ‘I have never been able to swim the patriarchy, and a space for dialogue. Africa Trade, c.1985 ‘Discourse is a primary tool against the she declared: ‘The show does not stand references the vast collection of properly and am very frightened of This series is a lamentation, an act of weapons used to marginalise and write in isolation. -

Phillips, M. the Case of the Absent Artist. a Body Of

The Case of the Absent Artist A Body of Evidence of Mike Phillips 1 The Case for the Defence. On the seventeenth of April 1962 Perry Mason, the legendary defence attorney, faced one of his most pataphysical cases. ‘The Case of the Absent Artist’ (CBS 1962) is an account of a transmogrification that resonates through digital arts practice to this day. The author of the popular comic strip ‘Zingy’, Gabe Philips, transforms from a cartoon- ist to a ‘serious’ painter, bifurcating in the process to become Otto Gervaert. This transformation is only completed when he (both Philips and Gervaert) is/are murdered, the artist(s) remains as a body of evi- dence and a body of work. Mason is faced with the absence left by the transformation of the artist; the absent artist (or artists) defines a new space, not emptiness but a place resonant with potential. The following is a re-investigation of this resonant place left by the artist – Philips/Gervaert and how this transformation of the artist is be- ing enacted with increasing frequency. This manifestation of trans- formation, duality and disappearance is symptomatic of a technologi- cal performativity evident in a series of projects and relationships that have informed the development of frameworks, articulated below as ‘Operating Systems’. As forensic tools these Operating Systems are ‘instruments’ or provocative prototypes that enhance our understand- ing of the world and our impact on it. In the case of the absent artist they probe the space that once held the artist to build a new body of evidence. This body of evidence itself builds on an evolutionary thread that has run through the collaborative work of i-DAT.org. -

M Caz CV Dec 2020 No Address

Mark Cazalet 1988-9 Commonwealth Universities Scholarship: Baroda University, Gujerat State, India 1986-7 French Consul National Studentship Award: L’Ecole Nationale Superieure des Beaux- Arts, Paris; awarded one-year residency at the Cite-Internationale-des-Arts, Paris 1983-6 Falmouth School of Art: BA Fine Art 1982-3 Chelsea School of Art: foundation course Solo Exhibitions 2021 The Stillness, the Dancing, Serena Morton Gallery, London Spaces: within and without, retrospective of Mark Cazalet’s vision, Clare Hall Cambridge 2019 Quiet Radiance, Serena Morton Gallery, London 2018 Resonances, Serena Morton Gallery, London 2016 Silent colour Meditation: a great cloud of witnesses, 153 heads, St Edmundsbury Cathedral 2015 Moments of Transformation, Curwen gallery, London 2014 Too serious to be serious, Lynne Strover Gallery, Cambridge 2012 The Ocean in a Tree, The Concert Hall Gallery, Snape Maltings, Suffolk 2010 A Plot of Ground, Jason Hicklin and Mark Cazalet, Beardsmore Gallery, London 2008 Everyday Epiphany, Beardsmore Gallery, London Stations of the Cross, Salisbury Cathedral 2006 Seeing as Beleiving, Catmose Gallery, Rutland Holyland, a painted pilgrimage, Michaelhouse Centre, Cambridge 2005 Travelling with open eyes, Guildford Cathedral On Shifting Ground, Images from Palestine & Israel, All Hallows by the Tower, London 2004 An Egyptian Apocrypha, St Katherine Cree, London 2002 Bath Rugby Residency Drawings, Museum of Rugby, Twickenham The Sound of Trees, Six Chapel Row Contemporary Art, Bath 2000 West London Stations of the Cross, -

Re-Recordings | List of Materials ------9 1) Selection of Material from the Recordings Project Archive, Policy 6 Documents and Art Documentation (ACAA)

Re-Recordings | List of Materials --------------------------------------------------------------------------- 9 1) Selection of material from the Recordings Project Archive, policy 6 documents and art documentation (ACAA) Recordings: a Select Bibliography of Contemporary African, Afro-Caribbean and Asian 5 British Art. London: INiva, 1996. Race, Sex and Class 5. Multi-Ethnic Education in further, Higher and Community Education, 1983 8 Box of Recordings Research Project and Drafts. Chelsea College of Art & Design Library Archive. Anti-Racist Film Programme. London, GLC, March/April 1985. London GLC/ London 3 Against Racism. 1985. The Arts and Ethnic Minorities: Action Plan. London: Arts Council of Great Britain, 1986 4 Ward, Liz. St.Martin’s School of Art Library: Collection Development, ILEA Muti-Ethnic 1 Review,Winter/Spring 1985 Chambers, Eddie. Blk Art Group Proposal to Art Colleges, 1983 Black Art in Britain: A bibliography of material held in the Library, Chelsea School of Art, 1986 Asian and Afro-Caribbean British art: a Bibliography of Material Held in the Library, 2 Chelsea College of Art & Design,1989. Art Libraries Journal, The Documentation of Black Artists, v.8, no.4 (Winter 1983) Black Arts in London no.50, 4-17 March 1986 7 African and Asian Visual Artists Archive (Flyer and cards) [Bristol],1990. Arts Council Arts & Ethnic Minorities Action Plan. London, February, 1996 ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 2) Artists’ multiples, artists’ books, ephemera and video Araeen, Rasheed. The Golden Verses: a Billboard Artwork… Artangel Trust, 1990 Chambers, Eddie. Breaking that Bondage: Plotting that Course. London: Black Art Gallery, 1984 Us and ‘Dem, The Storey Institute , Leicester, 1994. Postcard/Virginia Nimarkoh, 1993. Artist Book. The Image Employed, the use of narrative in Black art. -

Lubaina Himid

Lubaina Himid Hollybush Gardens launches its new space with an exhibition by Lubaina Himid, a painter and installation artist who has dedicated much of her thirty-year long career to uncovering marginalised and silenced histories, figures and cultural moments. Born in Zanzibar, Lubaina Himid was then brought up in North London by her mother, a Royal College of Art educated textile designer whose keen interest in patterns inspired her to follow an artistic path. Himid first took a BA in Theatre Design at Wimbledon College of Art in the mid-1970s, choosing this discipline for the connections it bore with radical politics, and in particular Black politics. While studying Cultural History at the Royal College of Art six years later, and by then deeply engaged in a struggle against the absence of representation of Black and Asian women in the art world, Lubaina Himid became committed to showing the work of her contem- poraries Sutapa Biswas, Sonia Boyce, Claudette Johnson, Ingrid Pollard, Veronica Ryan and Maud Sulter, alongside her own. She curated significant group exhibitions such as Five Black Women at the Africa Centre in 1983, Black Women Time Now at Battersea Arts Centre in 1983-84 and The Thin Black Line at the Institute for Contemporary Art in 1985, all of which were revisited in the temporary display Thin Black Line(s) at Tate Britain in 2011-12. In 1986, Himid exhibited her iconic installation A Fashionable Marriage at the Pentonville Gallery in London. Inspired by William Hogarth’s Marriage à-la-mode (1743), a series of six paintings satirising an arranged marriage gone wrong, Himid’s piece produced a biting critique of contemporary art and politics, and of their collusion. -

Re Imaging Donald Rodney

Re imaging Donald Rodney 1 Introduction Reimaging Donald Rodney explores the work of Black British artist Donald Rodney (1961 – 1998). It is the first UK exhibition to examine Rodney’s digital practice, and through new commissions expands on the potential of Rodney’s archive as a resource for challenging our conceptions of cultural, physical and social identity. Donald Rodney was considered to be He developed his artistic skills during one the most significant artists of his prolonged periods of hospitalisation, generation. Mark Sealy, Director of resulting in him regularly missing Autography ABP stated in an online school, due to his sickle cell condition. interview with TATE Britain for their After taking an arts foundation collection of Rodney’s work; course at Bournville School of Art in Birmingham he went on to Nottingham “[Along] with Donald, Keith Piper, Eddie Trent, where he met Keith Piper and Chambers and people like Sonia Boyce, Eddie Chambers. Chambers and Piper Lubaina Himid. Those characters in my espoused the notion of Black Art/Black view are really quite seminal in terms of Power, which derived largely from beginning to create an articulate voice… the USA through black writers and he was really interested in working with activists like Ron Karenga. Becoming Exhibition new media and new technologies. One a prominent member of the Blk Arts of the great tragedies is that he was Group, RRodney highlighted the Reimaging Donald Rodney aims to The new works developed for the becoming very articulate within this sociopolitical condition of Britain in Donald Rodney, from encapsulate the digital embodiment exhibition include doublethink (2015), space around the end of his career”.