Botticelli's Dancing Angels: Shaping Space in the Celestial Realm

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Feast of the Annunciation

1 Pope Shenouda III series 5 THE FEAST OF THE ANNUNCIATION BY HIS HOLINESS AMBA SHENOUDA III, POPE AND PATRIARCH OF ALEXANDRIA AND OF THE APOSTOLIC SEE OF ALL THE PREDICATION OF SAINT MARK Translated from the Arabic first edition of April 1997 Available from: http://www.copticchurch.net 2 All rights are reserved to the author His Holiness Pope Shenouda III Pope and Patriarch of the See of Alexandria and of all the Predication of the Evangelist St. Mark Name of the book: The Feast of the Annunciation Author: His Holiness Pope Shenouda III Editor: Orthodox Coptic Clerical College, Cairo First Edition: April 1997 Press: Amba Rueiss, (Offset) - The Cathedral - Abbassia Deposition number at "The Library": 97 / 475 977 - 5345 - 38 In the Name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit, the One God, Amen. You will read in this pamphlet about the Annunciation of the Nativity of Christ, glory be to Him, and the annunciations which preceded and succeeded it. It is the annunciation of salvation for the world. It is the first feast of the Lord. It is an annunciation of love, because the reason of the Incarnation and Redemption is the love of God for the world. The Lord Christ has offered to us rejoicing annunciations and has presented God to us as a loving Father. What shall we then announce to people? Let there be in your mouths, all of you, a rejoicing annunciation for everybody. Pope Shenouda III 3 The feast of the Annunciation comes every year on the 29th of Baramhat. -

Moma's Folk Art Museum and DS+R Scandal 14

017 Index MoMA's Folk Art Museum and DS+R 01 Editor´s Note Scandal 14 A Brief History of 02 Gabriela Salazar’s!In Advance Artwork Commission 22 of a Storm!Art Book Top Commissioned Promotion 26 Art Pieces by Top Commissioners of All Time 08 27 Contact Editor´s note Who were the first patrons in the history of art to commissioning artwork and what was their purpose? How has commissioning changed for the artist and for the entity requesting the art piece? What can be predicted as the future of the commissioning world? Our May issue explores the many and different ramifications of art commission in the past and in the present. Historical facts and recent scandals can make a quirky encapsulation of what is like to be commissioned to do art; to be commissioned an art piece for an individual, business, or government can sometimes be compared to making an agreement with the devil. “Commissioned artwork can be anything: a portrait, a wedding gift, artwork for a hotel, etc. Unfortunately, there are no universal rules for art commissions. Consequently, many clients take advantage of artists,” says Clara Lieu, an art critic for the Division of Experimental and Foundation studies and a professor at the Rhode Island School of Design. This issues aims to track down the history of ancient civilizations and the Renaissance in its relation to commissioned work, and its present manifestations in within political quarrels of 01 respectable art institutions. A Brief History of Artwork Commission: Ancient Rome and the Italian Renaissance An artwork commission is the act of soliciting the creation of an original piece, often on behalf of another. -

The Medici Palace, Cosimo the Elder, and Michelozzo: a Historiographical Survey

chapter 11 The Medici Palace, Cosimo the Elder, and Michelozzo: A Historiographical Survey Emanuela Ferretti* The Medici Palace has long been recognized as an architectural icon of the Florentine Quattrocento. This imposing building, commissioned by Cosimo di Giovanni de’ Medici (1389–1464), is a palimpsest that reveals complex layers rooted in the city’s architectural, urban, economic, and social history. A symbol – just like its patron – of a formidable era of Italian art, the palace on the Via Larga represents a key moment in the development of the palace type and and influenced every other Italian centre. Indeed, it is this building that scholars have identified as the prototype for the urban residence of the nobility.1 The aim of this chapter, based on a great wealth of secondary literature, including articles, essays, and monographs, is to touch upon several themes and problems of relevance to the Medici Palace, some of which remain unresolved or are still debated in the current scholarship. After delineating the basic construction chronology, this chapter will turn to questions such as the patron’s role in the building of his family palace, the architecture itself with regards to its spatial, morphological, and linguistic characteristics, and finally the issue of author- ship. We can try to draw the state of the literature: this preliminary historio- graphical survey comes more than twenty years after the monograph edited by Cherubini and Fanelli (1990)2 and follows an extensive period of innovative study of the Florentine early Quattrocento,3 as well as the fundamental works * I would like to thank Nadja Naksamija who checked the English translation, showing many kindnesses. -

TS Botticelli FRE 4C.Qxp 3/10/2009 1:41 PM Page 2

BOTTICELLIBOTTICELLI Émile Gebhart & Victoria Charles TS Botticelli FRE 4C.qxp 3/10/2009 1:41 PM Page 2 Text: Émile Gebhart and Victoria Charles Layout: BASELINE CO LTD 61A-63A Vo Van Tan Street 4th Floor District 3, Ho Chi Minh City Vietnam © Parkstone Press International, New York, USA © Confidential Concepts, Worldwide, USA All modification and reproduction rights reserved internationally. Unless otherwise stated, copyright for all artwork reproductions rests with the photographers who created them. Despite our research efforts, it was impossible to identify authorship rights in some cases. Please address any copyright claims to the publisher. ISBN: 978-1-78042-995-3 TS Botticelli FRE 4C.qxp 3/10/2009 1:41 PM Page 3 ÉMILE GEBHART Sandro Botticelli TS Botticelli FRE 4C.qxp 3/10/2009 1:41 PM Page 4 TS Botticelli FRE 4C.qxp 3/10/2009 1:41 PM Page 5 Contents Botticelli’s Youth and Education 7 Botticelli’s First Works 37 The Medici and Botticelli’s Pagan Initiation 67 Pagan, Mystical, and Oriental Visions 113 Botticelli’s Waning Days 179 Bibliography 252 List of Illustrations 253 TS Botticelli 4C ok.qxp 11/13/2009 10:22 AM Page 6 TS Botticelli FRE 4C.qxp 3/10/2009 1:41 PM Page 7 Botticelli’s Youth and Education TS Botticelli FRE 4C.qxp 3/10/2009 1:41 PM Page 8 TS Botticelli 4C.qxp 11/12/2009 5:17 PM Page 9 — Botticelli’s Youth and Education — lessandro di Mariano Filipepi, also known as “di Botticello” in homage to his first master, and A Sandro Botticelli to those who knew him, was born in Florence in 1445. -

American Art Museum Resources

Teachers ART RESOURCES The ART OF ROMARE BEARDEN Teacher Packets include a printed booklet with in-depth back- ground information, suggestions for student activities, supple- mental image CDs , and often with color study prints, timelines, and bibliographies. AN EYE FOR ART Focusing on Great Artists and Their Work Teaching Packet SK 651 This family-oriented resource brings together in one lively, activity-packed book a selection of forty art features from the National Gallery of Art’s popular quarterly NGAKids. Each feature introduces an artist and several works from the Gallery’s collections and is paired with activities to inspire crea- tive writing, focused looking, and artistic development in children ages 7 and up. Seven child- friendly chapters ranging from studying nature to breaking traditions are populated with a wide spectrum of artists, art mediums, nationalities, and time periods. This is an attractive gathering of art and information from the nation’s collection that lends itself to family enjoyment, classroom in- struction and homeschooling for the young. Artist include: Giuseppe, Romare Bearden, Osias Beert the Elder, George Bellows, Alexander Calder, Canaletto, Mary Cassatt, Chuck Close, John Constable, Jasper Francis Cropsey, Edgar Degas, Andre Derain, Dan Flavin, Angelico Fra, Filippo Lippi Fra, Paul Gauguin, Vincent Van Gogh and many more. Includes (20) paintings. SK 652 Art & Origin Myths, Heroes * Heroines, Ecology, and 19th Century America Four lessons—Greco-Roman Origin Myths, Heroes & Heroines, Art & Ecology, and 19th-Century America in Art & Literature—are tied to national curriculum standards. The packet includes pre- lesson activities, worksheets, student handouts about works of art and maps, and assessment and follow-up activities. -

Donatello's Terracotta Louvre Madonna

Donatello’s Terracotta Louvre Madonna: A Consideration of Structure and Meaning A thesis presented to the faculty of the College of Fine Arts of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts Sandra E. Russell May 2015 © 2015 Sandra E. Russell. All Rights Reserved. 2 This thesis titled Donatello’s Terracotta Louvre Madonna: A Consideration of Structure and Meaning by SANDRA E. RUSSELL has been approved for the School of Art + Design and the College of Fine Arts by Marilyn Bradshaw Professor of Art History Margaret Kennedy-Dygas Dean, College of Fine Arts 3 Abstract RUSSELL, SANDRA E., M.A., May 2015, Art History Donatello’s Terracotta Louvre Madonna: A Consideration of Structure and Meaning Director of Thesis: Marilyn Bradshaw A large relief at the Musée du Louvre, Paris (R.F. 353), is one of several examples of the Madonna and Child in terracotta now widely accepted as by Donatello (c. 1386-1466). A medium commonly used in antiquity, terracotta fell out of favor until the Quattrocento, when central Italian artists became reacquainted with it. Terracotta was cheap and versatile, and sculptors discovered that it was useful for a range of purposes, including modeling larger works, making life casts, and molding. Reliefs of the half- length image of the Madonna and Child became a particularly popular theme in terracotta, suitable for domestic use or installation in small chapels. Donatello’s Louvre Madonna presents this theme in a variation unusual in both its form and its approach. In order to better understand the structure and the meaning of this work, I undertook to make some clay works similar to or suggestive of it. -

The Magic of Donatello Andrew Butterfield

The Magic of Donatello Andrew Butterfield Sculpture in the Age of Donatello: smith Lorenzo Ghiberti, and another Renaissance Masterpieces from young Florentine goldsmith, Filippo Florence Cathedral Brunelleschi—the future architect— an exhibition at the Museum of came in second. A new era in the his- Biblical Art, New York City, tory of art had begun. February 20–June 14, 2015. Like all revolutions, the transfor- Catalog of the exhibition edited by mation of the arts in early-fifteenth- Timothy Verdon and Daniel M. Zolli. century Florence can never be fully Museum of Biblical Art/Giles, explained; at best we can only identify 200 pp., $49.95 some contributing causes. Stimulated in part by the city’s soaring prosperity The Museum of Biblical Art, lodged and growing hegemony, around 1400 in a relatively small space on Broad- the wealthy merchants who ran Flor- way near Lincoln Center, is now show- ence began to pour unprecedented ing nine sculptures by Donatello, one amounts of cash into new buildings, of the greatest of all Renaissance art- paintings, and sculptures. They were ists. Never before have so many of his proud of the architectural splendor best works been shown together in the of Florence and saw it as a sign of the United States. Antonio Quattrone/Opera di Santa Maria del Fiore, Florence city’s manifest destiny. This attitude Among the works on view is Don- was given voice by Leonardo Bruni, atello’s large sculpture of the Old Tes- who wrote around 1403–1404 in his tament prophet Habakkuk. “Speak, Panegyric to the City of Florence: damn you, speak!” Donatello, we are told, repeatedly shouted at the statue As soon as [visitors] have seen . -

The Image and Identity of the Alchemist in Seventeenth-Century

THE IMAGE AND IDENTITY OF THE ALCHEMIST IN SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY NETHERLANDISH ART Dana Kelly-Ann Rehn Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the coursework requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (Studies in Art History) School of History and Politics University of Adelaide July 2011 TABLE OF CONTENTS TITLE PAGE i TABLE OF CONTENTS ii LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS iii DECLARATION v ABSTRACT vi ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS vii 1 INTRODUCTION 1 2 ALCHEMY: A CONTROVERSIAL PROFESSION, PAST AND PRESENT 7 3 FOOLS AND CHARLATANS 36 4 THE SCHOLAR 68 5 CONCLUSION 95 BIBLIOGRAPHY 103 CATALOGUE 115 ii LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS FIGURE 1 Philip Galle (After Pieter Bruegel the Elder), The Alchemist, c.1558 118 FIGURE 2 Adriaen van de Venne, Rijcke-armoede („Rich poverty‟), 1636 119 FIGURE 3 Adriaen van Ostade, Alchemist, 1661 120 FIGURE 4 Cornelis Bega, The Alchemist, 1663 121 FIGURE 5 David Teniers the Younger, The Alchemist, 1649 122 FIGURE 6 David Teniers the Younger, Tavern Scene, 1658 123 FIGURE 7 David Teniers the Younger, Tavern Scene, Detail, 1658 124 FIGURE 8 Jan Steen, The Alchemist, c.1668 125 FIGURE 9 Jan Steen, Title Unknown, 1668 126 FIGURE 10 Hendrik Heerschop, The Alchemist, 1671 128 FIGURE 11 Hendrik Heerschop, The Alchemist's Experiment Takes Fire, 1687 129 FIGURE 12 Frans van Mieris the Elder, An Alchemist and His Assistant in a Workshop, c.1655 130 FIGURE 13 Thomas Wijck, The Alchemist, c.1650 131 FIGURE 14 Pierre François Basan, 1800s, after David Teniers the Younger, Le Plaisir des Fous („The Pleasure of Fools‟), 1610-1690 132 FIGURE 15 -

Freeing Leonardo Da Vinci's Fight for the Standard in the Hall of the Five

International Journal of Social Science Studies Vol. 5, No. 10; October 2017 ISSN 2324-8033 E-ISSN 2324-8041 Published by Redfame Publishing URL: http://ijsss.redfame.com Freeing Leonardo da Vinci’s Fight for the Standard in the Hall of the Five Hundred at Florence’s Palazzo Vecchio Antonio Cassella1 1President of Research Autism LLC (FL) and Director of Imerisya (Instituto merideño de investigación de la inteligencia social y del autismo, Mérida, Venezuela). Correspondence: Antonio Cassella, 1270 N. Wickham Rd. 16-613, Melbourne, FL, 32935, USA. Received: August 17, 2017 Accepted: September 1, 2017 Available online: September 18, 2017 doi:10.11114/ijsss.v5i10.2657 URL: https://doi.org/10.11114/ijsss.v5i10.2657 Abstract In June 2017, the author wrote an article in the International Journal of Social Science Studies in which he hypothesized that the Hall of the Five Hundred at Florence’s Palazzo Vecchio has been protecting the central piece of Leonardo da Vinci’s mural Battle of Anghiari: The Fight for the Standard (La Lotta per lo Stendardo) under Giorgio Vasari’s painting Battle of Marciano for 512 years now. On the evening of August 10, 2017, the author read a veiled message left by Vasari: The vertical line that passes through the center of the Battle of Marciano also passes through the center of the Fight for the Standard. On the evening of August 15, the author read a second secret message left by Vasari: The bottom of Leonardo’s Battle of Anghiari aligns with the floor of the Hall of the Five Hundred. -

Leonardo Da Vinci and the Persistence of Myth Emily Hanson

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) 1-1-2012 Inventing the Sculptor: Leonardo da Vinci and the Persistence of Myth Emily Hanson Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd Recommended Citation Hanson, Emily, "Inventing the Sculptor: Leonardo da Vinci and the Persistence of Myth" (2012). All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs). 765. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd/765 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY Department of Art History & Archaeology INVENTING THE SCULPTOR LEONARDO DA VINCI AND THE PERSISTENCE OF MYTH by Emily Jean Hanson A thesis presented to the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts May 2012 Saint Louis, Missouri ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wouldn’t be here without the help and encouragement of all the following people. Many thanks to all my friends: art historians, artists, and otherwise, near and far, who have sustained me over countless meals, phone calls, and cappuccini. My sincere gratitude extends to Dr. Wallace for his wise words of guidance, careful attention to my work, and impressive example. I would like to thank Campobello for being a wonderful mentor and friend, and for letting me persuade her to drive the nearly ten hours to Syracuse for my first conference, which convinced me that this is the best job in the world. -

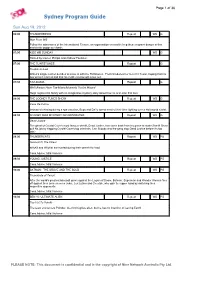

Sydney Program Guide

Page 1 of 36 Sydney Program Guide Sun Aug 19, 2012 06:00 THUNDERBIRDS Repeat WS G Man From Mi5 Follow the adventures of the International Rescue, an organisation created to help those in grave danger in this marionette puppetry classic. 07:00 KIDS WB SUNDAY WS G Hosted by Lauren Phillips and Andrew Faulkner. 07:00 THE FLINTSTONES Repeat G Trouble-In-Law Wilma's single mother decides to move in with the Flintstones. Fred introduces her to a rich Texan, hoping that the two will get married and that his mother-in-law will move out. 07:30 TAZ-MANIA Repeat G We'll Always Have Taz-Mania/Moments You've Missed Hugh regales the family with an imaginative mystery story about how he and Jean first met. 08:00 THE LOONEY TUNES SHOW Repeat WS G Casa De Calma Instead of relaxing during a spa vacation, Bugs and Daffy spend most of their time fighting over a Hollywood starlet. 08:30 SCOOBY DOO MYSTERY INCORPORATED Repeat WS G Dead Justice The ghost of Crystal Cove's most famous sheriff, Dead Justice, has come back from his grave to make Sheriff Stone quit his job by trapping Crystal Cove's top criminals. Can Scooby and the gang stop Dead Justice before it's too late? 09:00 THUNDERCATS Repeat WS PG Survival Of The Fittest WilyKit and WilyKat are hunted during their search for food. Cons.Advice: Mild Violence 09:30 YOUNG JUSTICE Repeat WS PG Cons.Advice: Mild Violence 10:00 BATMAN: THE BRAVE AND THE BOLD Repeat WS PG Triumvirate of Terror! After the world's greatest baseball game against the Legion of Doom, Batman, Superman and Wonder Woman face off against their arch-enemies Joker, Lex Luthor and Cheetah, who gain the upper hand by switching their respective opponents. -

Giorgio Vasari at 500: an Homage

Giorgio Vasari at 500: An Homage Liana De Girolami Cheney iorgio Vasari (1511-74), Tuscan painter, architect, art collector and writer, is best known for his Le Vile de' piu eccellenti architetti, Gpittori e scultori italiani, da Cimabue insino a' tempi nostri (Lives if the Most Excellent Architects, Painters and Sculptors if Italy, from Cimabue to the present time).! This first volume published in 1550 was followed in 1568 by an enlarged edition illustrated with woodcuts of artists' portraits. 2 By virtue of this text, Vasari is known as "the first art historian" (Rud 1 and 11)3 since the time of Pliny the Elder's Naturalis Historiae (Natural History, c. 79). It is almost impossible to imagine the history ofItalian art without Vasari, so fundamental is his Lives. It is the first real and autonomous history of art both because of its monumental scope and because of the integration of the individual biographies into a whole. According to his own account, Vasari, as a young man, was an apprentice to Andrea del Sarto, Rosso Fiorentino, and Baccio Bandinelli in Florence. Vasari's career is well documented, the fullest source of information being the autobiography or vita added to the 1568 edition of his Lives (Vasari, Vite, ed. Bettarini and Barocchi 369-413).4 Vasari had an extremely active artistic career, but much of his time was spent as an impresario devising decorations for courtly festivals and similar ephemera. He praised the Medici family for promoting his career from childhood, and much of his work was done for Cosimo I, Duke of Tuscany.