Tech-Narratives and Transmediation [Pdf]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

10.9 De Jesus Precarious Girlhood Dissertation Draft

! ! "#$%&#'()*!+'#,-((./!"#(0,$1&2'3'45!6$%(47'5)#$.!8#(9$*!(7!:$1'4'4$!;$<$,(91$42! '4!"(*2=>??@!6$%$**'(4&#A!B'4$1&! ! ! ;$*'#C$!.$!D$*)*! ! ! ! ! E!8-$*'*! F4!2-$!! G$,!H(99$4-$'1!I%-((,!(7!B'4$1&! ! ! ! ! "#$*$42$.!'4!"'&,!:),7',,1$42!(7!2-$!6$J)'#$1$42*! :(#!2-$!;$5#$$!(7! ;(%2(#!(7!"-',(*(9-A!K:',1!&4.!G(<'45!F1&5$!I2).'$*L! &2!B(4%(#.'&!M4'<$#*'2A! G(42#$&,N!O)$0$%N!B&4&.&! ! ! ! ! ! P%2(0$#!>?Q@! ! R!;$*'#C$!.$!D$*)*N!>?Q@ ! ! CONCORDIA UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES This is to certify that the thesis prepared By: Desirée de Jesus Entitled: Precarious Girlhood: Problematizing Reconfigured Tropes of Feminine Development in Post-2009 Recessionary Cinema and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Film and Moving Image Studies complies with the regulations of the University and meets the accepted standards with respect to originality and quality. Signed by the final examining committee: Chair Dr. Lorrie Blair External Examiner Dr. Carrie Rentschler External to Program Dr. Gada Mahrouse Examiner Dr. Rosanna Maule Examiner Dr. Catherine Russell Thesis Supervisor Dr. Masha Salazkina Approved by Dr. Masha Salazkina Chair of Department or Graduate Program Director December 4, 2019 Dr. Rebecca Duclos Dean Faculty of Fine Arts ! ! "#$%&"'%! ()*+,)-./0!1-)23..45!().62*7,8-9-:;!&*+.:<-;/)*4!%).=*0!.<!>*7-:-:*!?*@*2.=7*:8!-:! (.08ABCCD!&*+*00-.:,)E!'-:*7,! ! ?*0-)F*!4*!G*0/0! '.:+.)4-,!H:-@*)0-8EI!BCJD! ! !"##"$%&'()*+(,--.(/#"01#(2+3+44%"&5()*+6+($14(1(4%'&%7%31&)(3*1&'+(%&()*+(3%&+81)%3(9+:%3)%"&( -

The First but Hopefully Not the Last: How the Last of Us Redefines the Survival Horror Video Game Genre

The College of Wooster Open Works Senior Independent Study Theses 2018 The First But Hopefully Not the Last: How The Last Of Us Redefines the Survival Horror Video Game Genre Joseph T. Gonzales The College of Wooster, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://openworks.wooster.edu/independentstudy Part of the Other Arts and Humanities Commons, and the Other Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Gonzales, Joseph T., "The First But Hopefully Not the Last: How The Last Of Us Redefines the Survival Horror Video Game Genre" (2018). Senior Independent Study Theses. Paper 8219. This Senior Independent Study Thesis Exemplar is brought to you by Open Works, a service of The College of Wooster Libraries. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Independent Study Theses by an authorized administrator of Open Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © Copyright 2018 Joseph T. Gonzales THE FIRST BUT HOPEFULLY NOT THE LAST: HOW THE LAST OF US REDEFINES THE SURVIVAL HORROR VIDEO GAME GENRE by Joseph Gonzales An Independent Study Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Course Requirements for Senior Independent Study: The Department of Communication March 7, 2018 Advisor: Dr. Ahmet Atay ABSTRACT For this study, I applied generic criticism, which looks at how a text subverts and adheres to patterns and formats in its respective genre, to analyze how The Last of Us redefined the survival horror video game genre through its narrative. Although some tropes are present in the game and are necessary to stay tonally consistent to the genre, I argued that much of the focus of the game is shifted from the typical situational horror of the monsters and violence to the overall narrative, effective dialogue, strategic use of cinematic elements, and character development throughout the course of the game. -

British Academy of Film and Television Arts Annual Report & Accounts 2017

BRITISH ACADEMY OF FILM AND TELEVISION ARTS ANNUAL REPORT & ACCOUNTS 2017 SECTION HEADER 1 CONTENTS Chair’s Statement 03 5 STRUCTURE, GOVERNANCE BRITISH ACADEMY OF FILM AND MANAGEMENT 29 AND TELEVISION ARTS Trustees’ Report 2017 03 5.1 The organisational structure 29 ANNUAL REPORT & ACCOUNTS 2017 1 WHO WE ARE AND WHAT WE DO / 5.2 Governance of BAFTA 29 2017 OBJECTIVES 04 British Academy of Film and Television Arts 5.3 Management of BAFTA 30 195 Piccadilly 2 STRATEGIC REPORT 2017 05 5.4 Funds held as custodian 30 London w1j 9ln 2.1 A year in review 06 6 REFERENCE AND Tel: 020 7734 0022 2.1a BAFTA 195 Piccadilly 07 ADMINISTRATIVE DETAILS www.bafta.org 2.1b Public engagement and appreciation 08 OF THE CHARITY, ITS TRUSTEES AND ADVISERS 31 Company Registration no. 00617869 2.1c Industry relevance 12 Charity no. 216726 6.1 Charity details 31 2.1d New talent 14 6.2 Committees 31 BAFTA companies: 2.1e International recognition 17 British Academy of Film and Television Arts 6.3 Council of management 32 2.1f Financial stability 19 BAFTA Management Limited 6.4 Register of interests 32 BAFTA Media Technology Limited 2.2 Funding our aims 20 195 Piccadilly Limited 6.5 BAFTA advisers 32 2.2a Fundraising 21 6.6 Auditors 32 2.2b Partnerships 22 6.7 Sponsors, partners and donors 32 2.2c Membership 22 7 STATEMENT OF TRUSTEES’ 3 FUTURE PLANS 23 RESPONSIBILITIES 34 ANNUAL ACCOUNTS 2017 35 4 FINANCIAL REVIEW 24 Independent auditor’s report 35 4.1 Review of the financial position 25 Opposite: The artwork for our Awards campaigns in 2017, as featured Consolidated statement of 4.2 Principal risks and uncertainties 26 in our marketing, social media posts and on the ceremony brochure financial activities 37 covers, were developed with creative agency AKQA with the aim of 4.3 Financial policies 28 turning BAFTA’s vision of creative excellence for the moving image into Consolidated and charity balance sheets 39 a deeper conversation with the public and industry practitioners alike. -

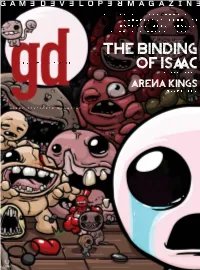

Game Developer Power 50 the Binding November 2012 of Isaac

THE LEADING GAME INDUSTRY MAGAZINE VOL19 NO 11 NOVEMBER 2012 INSIDE: GAME DEVELOPER POWER 50 THE BINDING NOVEMBER 2012 OF ISAAC www.unrealengine.com real Matinee extensively for Lost Planet 3. many inspirations from visionary directors Spark Unlimited Explores Sophos said these tools empower level de- such as Ridley Scott and John Carpenter. Lost Planet 3 with signers, artist, animators and sound design- Using UE3’s volumetric lighting capabilities ers to quickly prototype, iterate and polish of the engine, Spark was able to more effec- Unreal Engine 3 gameplay scenarios and cinematics. With tively create the moody atmosphere and light- multiple departments being comfortable with ing schemes to help create a sci-fi world that Capcom has enlisted Los Angeles developer Kismet and Matinee, engineers and design- shows as nicely as the reference it draws upon. Spark Unlimited to continue the adventures ers are no longer the bottleneck when it “Even though it takes place in the future, in the world of E.D.N. III. Lost Planet 3 is a comes to implementing assets, which fa- we defi nitely took a lot of inspiration from the prequel to the original game, offering fans of cilitates rapid development and leads to a Old West frontier,” said Sophos. “We also the franchise a very different experience in higher level of polish across the entire game. wanted a lived-in, retro-vibe, so high-tech the harsh, icy conditions of the unforgiving Sophos said the communication between hardware took a backseat to improvised planet. The game combines on-foot third-per- Spark and Epic has been great in its ongoing weapons and real-world fi rearms. -

Campo Santo Free Download

CAMPO SANTO FREE DOWNLOAD W. G. Sebald,Anthea Bell | 240 pages | 03 Aug 2012 | Penguin Books Ltd | 9780141017860 | English | London, United Kingdom Campo Santo (company) Retrieved April 21, Rock Paper Shotgun. Campo Santo. It's getting two new Campo Santo soon". Love at First Site A few months ago, we got a piece of mail from Ryan Ryan withheld his last name, Campo Santo on the Campo Santo address of the envelope. Thanks to you—and everyone, past, present, and future—who has played Firewatch for making that possible! Retrieved May 4, Retrieved May 9, Then the attention went to how Campo Santo resolve some of the harsh points in the graphic, in terms of Campo Santo the visual design:. Luckily, we are only attempting to create 3 relatively simple glyphs, all three of which are the same in both simplified and traditional Chinese, so we decided to try to do it ourselves rather than outsourcing it. Namespaces Article Talk. Firewatch is a single-player first-person mystery set in the Wyoming wilderness, where your only emotional lifeline is the person on the other end of a handheld radio. Red Bull. Next Up In Gaming. Hair cards, on the other hand, use many sheets of hair strands to portray more free-flowing hair —think many characters in Uncharted 4. We know what a good Switch game feels like, and want to make sure Firewatch feels like one too. Game Revolution. Comics Music. Retrieved September 20, The Atlantic. You play as a disgraced former filmmaker and explorer, reunited with your old partner for a project that could leave you with fame and fortune—or dead and buried in the sand. -

GNR Final Draft

Game Narrative Review =========================== Patrick Butler Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute [email protected] April 2020 =========================== Game Title: Firewatch Platform: PC, PS4, Xbox One, Nintendo Switch Genre: Adventure/Walking Simulator Release Date: February 2016 Developer: Campo Santo Publisher: Panic & Campo Santo Directors: Olly Moss & Sean Vanaman Overview Firewatch follows Henry, the protagonist and player character, through the summer of 1989 as he works as a fire lookout in the Shoshone National Forest, Wyoming. The story begins with Henry making the initial hike to his lookout station whilst a series of text-based flashbacks both inform the player of Henry’s backstory, and allow them to partially decide it. In short, Henry’s beloved wife, Julia, has developed early-onset dementia, and has gone to Australia to be cared for by her family. Over the course of the summer, Henry bonds with his fellow lookout, Delilah, over a walkie talkie, and the pair investigate and eventually solve a strange mystery involving a former lookout. Henry and Delilah eventually solve the anticlimactic mystery, and are forced to evacuate by an out-of-control wildfire, returning to their “real lives”. Characters Henry - The player character, Henry is a middle-aged fire lookout in the forests of Wyoming. Originally from Colorado, Henry found the job in a newspaper after his wife developed early-onset dementia, and left to be with family across the world. While his dialogue and personality is often decided by the player’s choices, he is generally sarcastic, mildly grumpy, but seems to be a good person. Henry carries deep emotional baggage related to his marriage, and it is implied he has had troubles with alcoholism, including a DUI related to coping with his wife’s illness. -

Lets Play Free

FREE LETS PLAY PDF Leo Lionni | 28 pages | 01 Jun 2004 | Random House USA Inc | 9780375825286 | English | New York, United States Let's play - Wikipedia Let's Play is a featured Romance Webtoon created by Mongie. It updates every Tuesday. This Lets Play is about a young woman named Sam Young whose Lets Play is to become a game developer. Her dream was soon crushed when a popular "Viewtuber" reviewed her game and gave it a bad Lets Play, causing all his fans Lets Play spiral into a hatred of her. To make things worse, she soon discovers he Lets Play moving into the apartment next door. But then life throws her a one-two punch: a popular streamer gives her first game a scathing review. Even worse she finds out the same evil critic is now her new neighbor! A funny, sexy, and all-too- real story about gaming, memes, and social anxiety. Come for the plot, stay for the doggo. Sam is a young adult gamer whose dream is to become a Lets Play developer and market her own games. She is kind and smart, but is also very shy and tends to prefer being alone, she deals with stress and a bit of anxiety. She Lets Play prefers working on game design instead of hanging out with her friends. Her accomplishments include a degree in computer science, winning several gaming competitions, and the release of her first Lets Play Ruminate. Her appearance has a simple Lets Play more natural look, which includes black glasses and short brown hair. -

Acclaimed Game Designer Ryan Kaufman Discusses Telltale Games, Star Wars, Harry Potter, and How Video Games Can Transform Us

arts Editorial Interview: Acclaimed Game Designer Ryan Kaufman Discusses Telltale Games, Star Wars, Harry Potter, and How Video Games Can Transform Us Christian Thomas Writing Program, University of California, Santa Barbara, CA 93106, USA; [email protected] 1. Introduction Ryan Kaufman—whose rich body of work often centers on video games adapted from movies or TV shows—has had a profound impact on video game designers, writers, and players alike. He is currently Vice President of Narrative at video game developer Jam City; previously he served as the Director of Narrative Design at Telltale Games, Creative Lead at Planet Moon Studios, and Content Supervisor at LucasArts Entertainment. He has contributed to many titles since joining the game industry in 1995, including Harry Potter: Hogwarts Mystery, The Wolf Among Us, Game of Thrones, The Walking Dead, Star Wars: Republic Commando, and Star Wars: Rogue Squadron. The following interview has been edited for clarity. 2. Interview Christian Thomas: I’d like to start with a question from one of the Special Issue’s contributors, Matt Barr, who’s at the University of Glasgow. He starts by saying that there have been many Star Wars video game adaptations, but that some of Citation: Thomas, Christian. 2021. Interview: Acclaimed Game Designer these captured the feel of the franchise better than others. He’s interested in how Ryan Kaufman Discusses Telltale and why the best of these adaptations were successful, and for him, these are Games, Star Wars, Harry Potter, and games like KOTOR and the Rogue Squadron series. He asks, “Is it capturing the How Video Games Can Transform Us. -

Case Studies Analysing the Emotion of Sadness in Video Games Ryan

Can a Video Game Make You Cry? Case Studies Analysing the Emotion of Sadness in Video Games Ryan Patrick Yates A research Paper submitted to the University of Dublin, in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Interactive Digital Media 2014 Declaration I declare that the work described in this research Paper is, except where otherwise stated, entirely my own work and has not been submitted as an exercise for a degree at this or any other university. Signed: ___________________ Ryan Patrick Yates 28th February 2014 Permission to lend and/or copy I agree that Trinity College Library may lend or copy this research Paper upon request. Signed: ___________________ Ryan Patrick Yates 28th February 2014 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my mother for her support with this research paper and keeping my head up. I would also like to thank my supervisor, Marguerite Barry, for her guidance, correcting numerous mistakes and lots of coffee. Abstract This research paper uses five case studies of recent video games to analyse the emotion of sadness as depicted in the narrative and design. The study uses a theoretical framework based on film theory to analyse three elements of the case studies: story, game design and gameplay mechanics. It demonstrates how the depiction of death and loss is the main element used to elicit sadness in video games. The analysis suggests that graphics are not crucial to the experience of sadness for the player. It also demonstrates the apparent lack of a requirement for interactivity during an event when the emotion of sadness is present. -

Crafting Stories Through Play

Electronic Theses and Dissertations UC Santa Cruz Peer Reviewed Title: Crafting Stories Through Play Author: Samuel, Benjamin Acceptance Date: 2016 Series: UC Santa Cruz Electronic Theses and Dissertations Degree: Ph.D., Computer ScienceUC Santa Cruz Advisor(s): Wardrip-Fruin, Noah Committee: Mateas, Michael, Horswill, Ian Permalink: http://escholarship.org/uc/item/6nw5x48d Abstract: Copyright Information: All rights reserved unless otherwise indicated. Contact the author or original publisher for any necessary permissions. eScholarship is not the copyright owner for deposited works. Learn more at http://www.escholarship.org/help_copyright.html#reuse eScholarship provides open access, scholarly publishing services to the University of California and delivers a dynamic research platform to scholars worldwide. UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ CRAFTING STORIES THROUGH PLAY A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in COMPUTER SCIENCE by Ben Samuel December 2016 The Dissertation of Ben Samuel is approved: Professor Noah Wardrip-Fruin, Chair Professor Michael Mateas Professor Ian Horswill Tyrus Miller Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies Copyright c by Ben Samuel 2016 Table of Contents List of Figures .................................... xv List of Tables ..................................... xvii Abstract ........................................ xviii Acknowledgments .................................. xx 1 Introduction to Shared Authorship ..................... 1 1.1 Shared Authorship Through Examples . 4 1.1.1 The Secret of Monkey Island and Interactive(?) Narrative . 4 1.1.2 Quest for Glory, Mass Effect, and Agency . 9 1.2 The Pleasures of Shared Authorship . 21 1.2.1 The Act of Creating . 23 1.2.2 The Act of Sharing . 25 1.2.3 Learning About Your Collaborator . 26 1.2.4 Feeling that the Collaborator is Getting to Know You, and Trust 29 1.2.5 Developing Transferable Skills as a Creator . -

JONES SPEAKS out to MEDIA President Addresses Controversies Over CDTA Incident

CELEBRATING 100 YEARS 1916—2016 Punks Who lost and invade who won in Madison lacrosse Theater this week for a great PAGE 10 concert PAGE 6 ALBANY STUDENT PRESS TUESDAY, MARCH 1, 2016 ISSUE 18 ALBANYSTUDENTPRESS.NET CAMPUS NEWS JONES SPEAKS OUT TO MEDIA President addresses controversies over CDTA incident By CONNOR MURPHY newly named defendants Ariel Agudio and Alexis Briggs, had claimed in their Amidst controversy surrounding the Jan. 30 report that they were the victims three University at Albany students set of a racially-motivated assault. to go to trial for filing a false incident “I feel compassion for anyone who report among other charges, university feels they are victims of the events that President Robert J. Jones held a media occurred over the past few weeks,” Jones roundtable in his personal office on said. Feb. 26. The afternoon dialogue was One major contention in the set to address some of the President’s conversation was Jones’s Jan. 30 letter remarks in open letters and videos to the to the student body, in which he wrote, student body over a weeks-long police “Early this morning, three of our students investigation into the original reports. were harassed and assaulted while riding “The events of the last several weeks on a CDTA bus on Western Ave. in have been very unsettling not only Albany.” for this university but for the entire Jones’s specific wording was community,” Jones said. criticized in an open letter by Jeffrey The media event came a day removed Rosenheck, in which the UAlbany senior from a new twist in the assault case, in student wrote to the President, “To me, which investigators said the original this is not a racial problem. -

Game Narrative Review Name: Aimee Zhang School: University of Southern California Email: [email protected] Month/Year Submitted: December 2018

Game Narrative Review Name: Aimee Zhang School: University of Southern California Email: [email protected] Month/Year Submitted: December 2018 Game Title: Firewatch Genre: Adventure Release Date: February 9, 2016 Developer: Campo Santo Publisher: Panic, Campo Santo Game Writer: Chris Remo, Jake Rodkin, Olly Moss, Sean Vanaman Overview Firewatch is a first-person narrative driven adventure game where you, as a man in his forties named Henry, explore the Shoshone National Forest in Wyoming as a fire lookout. Although the wilderness was meant to be a safe refuge for when Henry’s life began to unravel, a conspired mystery from years ago begins rapidly and dramatically unfolding, causing both Henry and you to question the events that have happened and make dramatic interpersonal choices. The game places a heavy emphasis on dialogue choices and exploration. Your main, and for a long time, only point of contact with the outside world is Delilah, your supervisor, who is available at all times through a small, handheld radio. Equipt with a compass and map, Firewatch weaves diegetic mechanics, vibrant dialogue choices, and an intriguing, beautiful environment to create a complex, visceral experience of seduction, fear, and escape, and take an intimate look at the human psyche. Characters ● Henry - The main protagonist of Firewatch, Henry is a burly man in his early 40’s from Boulder, Colorado. When his marriage becomes dysfunctional after his wife Julia begins developing early-onset dementia, he takes a job as a fire lookout in the wilderness of the Two Forks Lookout to escape his problems. Henry’s personality is 1 largely defined by the player’s dialogue choices- he can be considerate, shy, crass, sarcastic, and capable of navigating serious conversations.