Feature Article: XML and the Second Generation Web: May 1999

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oauth 2.0 Dynamic Client Registration Management Protocol Draft-Jones-Oauth-Dyn-Reg-Management-00

OAuth Working Group J. Richer TOC Internet-Draft The MITRE Corporation Intended status: Standards Track M. Jones Expires: August 1, 2014 Microsoft J. Bradley Ping Identity M. Machulak Newcastle University January 28, 2014 OAuth 2.0 Dynamic Client Registration Management Protocol draft-jones-oauth-dyn-reg-management-00 Abstract This specification defines methods for management of dynamic OAuth 2.0 client registrations. Status of this Memo This Internet-Draft is submitted in full conformance with the provisions of BCP 78 and BCP 79. Internet-Drafts are working documents of the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF). Note that other groups may also distribute working documents as Internet-Drafts. The list of current Internet-Drafts is at http://datatracker.ietf.org/drafts/current/. Internet-Drafts are draft documents valid for a maximum of six months and may be updated, replaced, or obsoleted by other documents at any time. It is inappropriate to use Internet- Drafts as reference material or to cite them other than as “work in progress.” This Internet-Draft will expire on August 1, 2014. Copyright Notice Copyright (c) 2014 IETF Trust and the persons identified as the document authors. All rights reserved. This document is subject to BCP 78 and the IETF Trust's Legal Provisions Relating to IETF Documents (http://trustee.ietf.org/license-info) in effect on the date of publication of this document. Please review these documents carefully, as they describe your rights and restrictions with respect to this document. Code Components extracted from this document must include Simplified BSD License text as described in Section 4.e of the Trust Legal Provisions and are provided without warranty as described in the Simplified BSD License. -

The Atom Project

The Atom Project Tim Bray, Sun Microsystems Paul Hoffman, IMC Recent Numbers On June 23, 2004 (according to Technorati.com): • There were 2.8 million feeds tracked • 14,000 new blogs were created • 270,000 new updates were posted Technology: How Syndication Works Now 1. Publication makes an XML document available at a well-known URI describing recent updates 2. Clients retrieve it regularly (slow polling) 3. That’s all! Technology: What’s In a Syndication Feed • One Channel: Title, URI, logo, generator, copyright, author • Multiple Items: Author, title, URI, guid, date(s), category(ies), description (excerpt/summary/ full-text) Species of RSS Currently Observed in the Wild • RSS 0.9: Netscape, RDF-based • RSS 0.91: Netscape, non-RDF • RSS 1.0*: Ad-hoc group, RDF-based • RSS 0.92*: UserLand, non-RDF • RSS 2.0*: UserLand, non-RDF * significant market share Data Format Problems Too many formats, they’re vaguely specified, there are technical issues with embedded markup, relative URIs, XML namespaces, and permanent identifiers. The personality & political problems are much worse. Scaling and security may be OK, because it’s all HTTP. The Protocol Landscape The Blogger and MetaWeblog “APIs” are quick hacks based on XML-RPC. They lack extensibility, standards-friendliness, security, authentication and a future. Atom, Pre-IETF • Launched Summer 2003 by Sam Ruby • Quick buy-in from major vendors • Quick buy-in from backers of all RSS species, except RSS 2.0 • Active wiki at http://www.intertwingly.net/wiki/ pie Atom in the IETF • Charter • Documents • Mailing list • Not meeting here Starting the Atompub charter • Floated in mid-April 2004 • Some tweaking but no major glitches from the first proposal • Decided to have Sam Ruby be the WG secretary • Was almost ready for the IESG to approve in mid-May, then... -

Extensible Markup Language (XML) 1.0 (Fifth Edition) W3C Recommendation 26 November 2008

Extensible Markup Language (XML) 1.0 (Fifth Edition) W3C Recommendation 26 November 2008 This version: http://www.w3.org/TR/2008/REC-xml-20081126/ Latest version: http://www.w3.org/TR/xml/ Previous versions: http://www.w3.org/TR/2008/PER-xml-20080205/ http://www.w3.org/TR/2006/REC-xml-20060816/ Editors: Tim Bray, Textuality and Netscape <[email protected]> Jean Paoli, Microsoft <[email protected]> C. M. Sperberg-McQueen, W3C <[email protected]> Eve Maler, Sun Microsystems, Inc. <[email protected]> François Yergeau Please refer to the errata for this document, which may include some normative corrections. The previous errata for this document, are also available. See also translations. This document is also available in these non-normative formats: XML and XHTML with color-coded revision indicators. Copyright © 2008 W3C® (MIT, ERCIM, Keio), All Rights Reserved. W3C liability, trademark and document use rules apply. Abstract The Extensible Markup Language (XML) is a subset of SGML that is completely described in this document. Its goal is to enable generic SGML to be served, received, and processed on the Web in the way that is now possible with HTML. XML has been designed for ease of implementation and for interoperability with both SGML and HTML. Status of this Document This section describes the status of this document at the time of its publication. Other documents may supersede this document. A list of current W3C publications and the latest revision of this technical report can be found in the W3C technical reports index at http://www.w3.org/TR/. -

Tim Bray 1 Tim Bray

Tim Bray 1 Tim Bray Tim Bray Born Timothy William Bray June 21, 1955 Residence Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada Website http:/ / www. tbray. org/ ongoing/ Timothy William Bray (born June 21, 1955) is a Canadian software developer and entrepreneur. He co-founded Open Text Corporation and Antarctica Systems. Bray was Director of Web Technologies at Sun Microsystems from early 2004 to early 2010. Since then he has served as a Developer Advocate at Google, focusing on Android.[1] Early life Bray was born on June 21, 1955 in Alberta, Canada. He grew up in Beirut, Lebanon and graduated in 1981 with a Bachelor of Science (double major in Mathematics and Computer Science) from the University of Guelph in Guelph, Ontario. Tim described his switch of focus from Math to Computer Science this way: "In math I’d worked like a dog for my Cs, but in CS I worked much less for As—and learned that you got paid well for doing it."[2] In June 2009, he received an honorary Doctor of Science degree from the University of Guelph.[3] Fresh out of university, Bray joined Digital Equipment Corporation in Toronto as a software specialist. In 1983, Bray left DEC for Microtel Pacific Research. He joined the New Oxford English Dictionary project at the University of Waterloo in 1987 as its manager. It was during this time Bray worked with SGML, a technology that would later become central to both Open Text Corporation and his XML and Atom standardization work. Tim Bray 2 Entrepreneurship Waterloo Maple Tim Bray served as the part-time CEO of Waterloo Maple Inc. -

Tim Bray [email protected] · Tbray.Org · @Timbray · +Timbray Left: 1997 Right: 2010 Java.Com Php.Net Rubyonrails.Org Djangoproject.Com Nodejs.Org

Does the browser have a future? Tim Bray [email protected] · tbray.org · @timbray · +TimBray Left: 1997 Right: 2010 java.com php.net rubyonrails.org djangoproject.com nodejs.org developer.android.com/reference/android/os/Vibrator.html Functional thinking with Erlang counter_loop(Count) -> incr(Counter) -> receive Counter ! { incr }. { incr } -> ! counter_loop(Count + 1); find_count(Counter) -> { report, To } -> Counter ! { report, self() }, To ! { count, Count }, receive counter_loop(Count) { count, Count } -> end. Count end. Scalable parallel counters! tbray.org/ongoing/When/200x/2007/09/21/Erlang clojure.org scala-lang.org fndIDP.appspot.com c := make(chan SearchResult) go timeout(c) for _, searcher := range Searchers { go searcher.Search(email, c, handles) } bestStrength := -1 outstanding := len(Searchers) bestResult = SearchResult{TimeoutType, []IDP{}} for outstanding > 0 { result := <-c outstanding-- if result.rtype == TimeoutType { break // timed out, don't wait for trailers } if len(result.idps) == 0 { continue // a result that found nothing, ignore it } resultClass := ResultStrengths[result.rtype] if resultClass.verified { bestResult = result break // verified results trump all others } if resultClass.strength > bestStrength { bestStrength = resultClass.strength bestResult = result } else if resultClass.strength == bestStrength { bestResult.idps = merge(bestResult.idps, result.idps) } } ... func timeout(c chan SearchResult) { time.Sleep(2000 * time.Millisecond) c <- SearchResult{rtype: TimeoutType} } twitter.com/levwalkin/status/510197979542614016/photo/1 -

An Introduction to Georss: a Standards Based Approach for Geo-Enabling RSS Feeds

Open Geospatial Consortium Inc. Date: 2006-07-19 Reference number of this document: OGC 06-050r3 Version: 1.0.0 Category: OpenGIS® White Paper Editors: Carl Reed OGC White Paper An Introduction to GeoRSS: A Standards Based Approach for Geo-enabling RSS feeds. Warning This document is not an OGC Standard. It is distributed for review and comment. It is subject to change without notice and may not be referred to as an OGC Standard. Recipients of this document are invited to submit, with their comments, notification of any relevant patent rights of which they are aware and to provide supporting do Document type: OpenGIS® White Paper Document subtype: White Paper Document stage: APPROVED Document language: English OGC 06-050r3 Contents Page i. Preface – Executive Summary........................................................................................ iv ii. Submitting organizations............................................................................................... iv iii. GeoRSS White Paper and OGC contact points............................................................ iv iv. Future work.....................................................................................................................v Foreword........................................................................................................................... vi Introduction...................................................................................................................... vii 1 Scope.................................................................................................................................1 -

AI, Robotics, and the Future of Jobs” Available At

NUMBERS, FACTS AND TRENDS SHAPING THE WORLD FOR RELEASE AUGU.S.T 6, 2014 FOR FURTHER INFORMATION ON THIS REPORT: Aaron Smith, Senior Researcher, Internet Project Janna Anderson, Director, Elon University’s Imagining the Internet Center 202.419.4372 www.pewresearch.org RECOMMENDED CITATION: Pew Research Center, August 2014, “AI, Robotics, and the Future of Jobs” Available at: http://www.pewinternet.org/2014/08/06/future-of-jobs/ 1 PEW RESEARCH CENTER About This Report This report is the latest in a sustained effort throughout 2014 by the Pew Research Center’s Internet Project to mark the 25th anniversary of the creation of the World Wide Web by Sir Tim Berners-Lee (The Web at 25). The report covers experts’ views about advances in artificial intelligence (AI) and robotics, and their impact on jobs and employment. The previous reports in this series include: . A February 2014 report from the Pew Research Center’s Internet Project tied to the Web’s anniversary looking at the strikingly fast adoption of the Internet and the generally positive attitudes users have about its role in their social environment. A March 2014 Digital Life in 2025 report issued by the Internet Project in association with Elon University’s Imagining the Internet Center focusing on the Internet’s future more broadly. Some 1,867 experts and stakeholders responded to an open-ended question about the future of the Internet by 2025. One common opinion: the Internet would become such an ingrained part of the environment that it would be “like electricity”—less visible even as it becomes more important in people’s daily lives. -

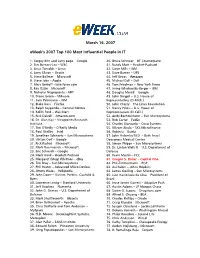

Eweek's 2007 Top 100 Most Influential People in IT

March 16, 2007 eWeek's 2007 Top 100 Most Influential People in IT 1. Sergey Brin and Larry page – Google 40. Bruce Schneier – BT Counterpane 2. Tim Berners-Lee – W3C 41. Randy Mott – Hewlett-Packard 3. Linus Torvalds – Linux 42. Steve Mills – IBM 4. Larry Ellison – Oracle 43. Dave Barnes – UPS 5. Steve Ballmer – Microsoft 44. Jeff Bezos – Amazon 6. Steve Jobs – Apple 45. Michael Dell – Dell 7. Marc Benioff –Salesforce.com 46. Tom Friedman – New York Times 8. Ray Ozzie – Microsoft 47. Irving Wladawsky-Berger – IBM 9. Nicholas Negroponte – MIT 48. Douglas Merrill – Google 10. Diane Green – VMware 49. John Dingell – U.S. House of 11. Sam Palmisano – IBM Representatives (D-Mich.) 12. Blake Ross – Firefox 50. John Cherry – The Linux Foundation 13. Ralph Szygenda – General Motors 51. Nancy Pelosi – U.S. House of 14. Rollin Ford – Wal-Mart Representatives (D-Calif.) 15. Rick Dalzell – Amazon.com 52. Andy Bechtolsheim – Sun Microsystems 16. Dr. Alan Kay – Viewpoints Research 53. Rob Carter – FedEx Institute 54. Charles Giancarlo – Cisco Systems 17. Tim O’Reilly – O’Reilly Media 55. Vikram Akula – SKS Microfinance 18. Paul Otellini – Intel 56. Robin Li – Baidu 19. Jonathan Schwartz – Sun Microsystems 57. John Halamka M.D. – Beth Israel 20. Vinton Cerf – Google Deaconess Medical Center 21. Rick Rashid – Microsoft 58. Simon Phipps – Sun Microsystems 22. Mark Russinovich – Microsoft 59. Dr. Linton Wells II – U.S. Department of 23. Eric Schmidt – Google Defense 24. Mark Hurd – Hewlett-Packard 60. Kevin Martin – FCC 25. Margaret (Meg) Whitman - eBay 61. Gregor S. Bailar – Capital One 26. Tim Bray – Sun Microsystems 62. -

Issues in Web Frameworks

ISSUES IN WEB FRAMEWORKS Tim Bray Director of Web Technologies Sun Microsystems Big Hot Issues Maintainability Scaling Developer Developer Tools Speed Intrinsic Integration In-Stack “Web 2.0” Identity External Issues in Scaling Observability Load balancing File I/O CPU Shared-nothing DBMS Issues in Developer Speed Compilation File I/O step? Code Size Deployment step? Configuration process Issues in Developer Tools Templating IDE How many tools? O/R Mapping Documentation Performance Issues in Maintainability MVC Code size Language count Object Readability orientation Comparing Intrinsics PHP Rails Java Scaling Dev Speed Dev Tools Maintainability Comparing Intrinsics Which is most PHP Rails Java important? Scaling Dev Speed Dev Tools Maintainability The Identity Problem The usual approach: “Make a Integration, SOA, USERS table.”and Web Services Integration, SOA, and Web Services Integration, SOA, and Web Services Stack Integration Options Download & Integration,Vendor- SOA, build: Apache, andintegrated Web Services PHP, MySQL, LAMP stack. add-on packages. Integration, SOA, and Web Services Apache, MySQL, PHP, Perl, Squid cooltools.sunsource.net/coolstack/index.html External integration Issues PHP will never go away. Rails will never go away. Java will never go away. .NET will never go away. The network is the computer. The network is heterogeneous. How do we get work done? SOA: WS-* is the Official Answer 36 specs, about 1,000 pages total. (msdn.microsoft.com/webservices/webservices/understanding/specs/default.aspx) Is WS-* A Little Bit Too Complex? SOA: An Alternative View Web Services: The Alternative Be like the Web! The theory: REST (Representational State Transfer). The practice: XML + HTTP. In action today at: Google, Amazon, AOL, Yahoo!, many others. -

The Atom Syndication Format

Network Working Group M. Nottingham, Editor Request for Comments: 4287 R. Sayre, Editor Category: Standards Track December 2005 The Atom Syndication Format Status of this Memo This document specifies an Internet standards track protocol for the Internet community, and requests discussion and suggestions for improvements. Please refer to the current edition of the “Internet Official Protocol Standards” (STD 1) for the standardization state and status of this protocol. Distribution of this memo is unlimited. Copyright Notice Copyright © The Internet Society (2005). All Rights Reserved. Abstract This document specifies Atom, an XML-based Web content and metadata syndication format. RFC 4287 Atom Format December 2005 Table of Contents 1 Introduction...............................................................................................................................................................4 1.1 Examples................................................................................................................................................................4 1.2 Namespace and Version........................................................................................................................................ 5 1.3 Notational Conventions......................................................................................................................................... 6 2 Atom Documents.......................................................................................................................................................7 -

A Use Case Diagram Is Useful When You Are Describing Requirements For

China Seed Market To Hit $3.9 Billion! Shandong Zhouyuan Seed and Nursery Co., Ltd (SZSN) $0.28 UP 16.6% China is the second largest seed market in the world. China's current market is $2.9 Billion annually and experts forecast it to hit $3.9 Billion in the next 2.5 years. SZSN is already expanding to keep ahead of the demand. Read the news, and watch for more Monday. Get on SZSN! You agree to comply strictly with all such laws and regulations and acknowledge that you have the responsibility to obtain such licenses to export, re-export, o r import as may be required. With the JavaBeans API, you can create reusable, platform-independent components . Panelists: Rich Green Executive Vice President, Software Sun Microsystems, Inc. If Software or Information is being acquired by or on behalf of the U. We hope you join us again next year. Excellent Good Fair Poor Comments: If you would like a reply to your com ment, please submit your email address: Note: We may not respond to all submitte d comments. Each of these actors is external to the system and only interacts with the syste m. SMP is an essential resource for developers, programmers and system administrato rs of all levels working with Java and other Sun technologies. Download Today and enter for a chance to win an Apple iPod Nano. Support for multiple users. We are attending some of the sessions and writing articles and blogs to cover th e event. The exception handler chosen is said to catch the exception. -

Julianne Nyhan Andrew Flinn Towards an Oral History of Digital

Springer Series on Cultural Computing Julianne Nyhan Andrew Flinn Computation and the Humanities Towards an Oral History of Digital Humanities Springer Series on Cultural Computing Editor-in-Chief Ernest Edmonds, University of Technology, Sydney, Australia Editorial Board Frieder Nake, University of Bremen, Bremen, Germany Nick Bryan-Kinns, Queen Mary University of London, London, UK Linda Candy, University of Technology, Sydney, Australia David England, Liverpool John Moores University, Liverpool, UK Andrew Hugill, De Montfort University, Leicester, UK Shigeki Amitani, Adobe Systems Inc., Tokyo, Japan Doug Riecken, Columbia University, New York, USA Jonas Lowgren, Linköping University, Norrköping, Sweden More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/10481 Julianne Nyhan • Andrew Flinn Computation and the Humanities Towards an Oral History of Digital Humanities Julianne Nyhan Andrew Flinn Department of Information Studies Department of Information Studies University College London (UCL) University College London (UCL) London, UK London, UK ISSN 2195-9056 ISSN 2195-9064 (electronic) Springer Series on Cultural Computing ISBN 978-3-319-20169-6 ISBN 978-3-319-20170-2 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-20170-2 Library of Congress Control Number: 2016942045 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and the Author(s) 2016. This book is published open access. Open Access This book is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution- Noncommercial 2.5 License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/cc by-nc/2.5/) which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited. The images or other third party material in this book are included in the work’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if such material is not included in the work’s Creative Commons license and the respective action is not permitted by statutory regulation, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to duplicate, adapt or reproduce the material.