Bribery & Corruption

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Banco Espírito Santo, S.A. BES Finance Ltd

PROSPECTUS Banco Espírito Santo, S.A. (Incorporated with limited liability in Portugal) (acting through its head office or its Madeira Free Trade Zone branch or its Cayman Islands branch or its London branch or its Luxembourg branch) and BES Finance Ltd. (Incorporated with limited liability in the Cayman Islands) unconditionally and irrevocably guaranteed by Banco Espírito Santo, S.A. (Incorporated with limited liability in Portugal) (acting through its London branch) €20,000,000,000 EURO MEDIUM TERM NOTE PROGRAMME This Prospectus is valid for the purpose of the listing of Notes on the Official List of the Luxembourg Stock Exchange and the admission to trading of the Notes on the regulated market of the Luxembourg Stock Exchange, for a period of one year from the date of publication. Any Notes (as defined below) issued under the Programme on or after the date of this Prospectus are issued subject to the provisions herein. This Prospectus does not affect any Notes already issued. Under the €20,000,000,000 Euro Medium Term Note Programme (the “Programme”), each of Banco Espírito Santo, S.A. (the “Bank” or “BES”), acting through its head office or its Madeira Free Trade Zone branch or its Cayman Islands branch or its London branch or its Luxembourg branch, and BES Finance Ltd. (“BES Finance” and, together with the Bank in its capacity as an issuer of Notes under the Programme, the “Issuers” and each an “Issuer”) may from time to time and, subject to applicable laws and regulations, issue notes (the “Notes”, which will include Senior Notes, Dated Subordinated Notes, Undated Subordinated Notes and, in the case of the Bank acting through its head office only, Undated Deeply Subordinated Notes (as such terms are defined below)) denominated in any currency agreed between the Issuer of such Notes (the “relevant Issuer”) and the relevant Dealer (as defined below). -

The European English Messenger

The European English Messenger Volume 24.1 – Summer 2015 Contents ESSE MATTERS Liliane Louvel, The ESSE President‟s Column. Password for the online version 2 ESSE Book Grants 5 Martin A. Kayman, Printing the Messenger: The End of an Era 6 European Journal of English Studies, Forthcoming Issues 11 13th ESSE Conference, Galway 2016 14 LANGUAGE IN USE Maurizio Gotti, Investigating Academic Identity Traits 15 Alessandra Molino, Checking comprehension in English-medium lectures in technical and 22 scientific fields Karin Aijmer, What I mean is- what is it doing in conversational interaction? 29 Nikola Dobrić, Quality Measurements of Error Annotation - Ensuring Validity through 36 Reliability REVISITING LITERATURE Rolf Breuer, From Theories of Deviation to Theories of Fictionality: The Definition of 42 Literature Fiona Robertson, Walter Scott and the Restoration of Europe 46 INTERVIEW Abel Debritto, Small Press Legends. The Best-Known of the Unknown Writers. An 57 Interview with Gerald Locklin Giuseppina Cortese, Wording a Life with Words. In Conversation with Carla Vaglio 65 POETRY James Robertson 70 Ross Donlon 73 SUMMER COURSE REPORTS 77 REVIEWS 78 ESSE BOARD MEMBERS: NATIONAL REPRESENTATIVES 96 1 The European English Messenger, 24.1 (2015) The ESSE President’s Column Liliane Louvel Those of you who read my column in last winter‘s issue of the Messenger already know how successful our 12th ESSE Conference in Košice was. We still cherish its memory, recalling the various delights (both academic and social) it held for us, and most of us are already looking forward to enjoying the same kind of experience again. This will be in 2016 at the 13th ESSE Conference in Galway, for the National University of Ireland is the location of our next conference. -

Besart Banco Espírito Santo Collection the Present: an Infinite Dimension

BES ART_Capa_NOR.indd 1 17/12/08 19:15:09 _BES ART_UK NOR.indd 1 22/12/08 13:39:20 _BES ART_UK NOR.indd 2 22/12/08 13:39:20 BESart Banco Espírito Santo Collection The Present: An Infinite Dimension _BES ART_UK NOR.indd 2 22/12/08 13:39:20 _BES ART_UK NOR.indd 3 22/12/08 13:39:21 _BES ART_UK NOR.indd 4 22/12/08 13:39:21 When speaking to me about photography, a Brazilian friend of mine read an excerpt from Roland Barthes’ Camera Lucida, which to me clarifies the mystery of the process: ‘What photography reproduces to infinity only happened once. It mechanically repeats what could never be repeated existentially.’ Also, ‘photo- graphy is nothing more than an alternate line of “Look”, “See”, “Here it is”; it points to a certain opposite.’ The Banco Espírito Santo photography collection allows for this ‘opposite’ experience through an anthological vision of photographic production from the 1980s to our current times. This collection travels through signs but also through the technical evolution of photographic representation. It shows the infinite diversity of contemporary production: from portrait to landscape, from conceptual art to photo-journalism, whether using the traditional principles of the analogue negative or the newest digital and image processing techniques. The BESart collection exhibited here is the most significant collection of con- temporary photography in Portugal, comprising work from modern artists to the youngest generation of creators. The public can now share this line of ‘Look’, ‘See’, ‘Here it is’ with us. José Berardo Honorary Chairman of the Fundação de Arte Moderna e Contemporânea – Colecção Berardo _BES ART_UK NOR.indd 4 22/12/08 13:39:21 _BES ART_UK NOR.indd 5 22/12/08 13:39:21 _BES ART_UK NOR.indd 6 22/12/08 13:39:21 Throughout its entire history, the Banco Espírito Santo has been active in cultural patronage, for instance with the Ricardo Espírito Santo Silva Foundation. -

Apresentação Do Powerpoint

Banca e Seguros BES Special Report/ Resumo Especial BES Special Report Banco Espírito Santo / Novo Banco Special Report Last Update | Última Actualização: 23/12/2014 Prepared by PE Probe | Preparado por PE Probe Copyright © 2014 Portugal Economy Probe PE Probe Portugal Economy Probe (PE Probe) All rights reserved Banca e Seguros BES Special Report/ Resumo Especial BES Timeline of Events / Cronologia de Eventos: 2011 • OCT 24: Banco Espírito Santo “doesn’t pretend to use the special recapitalization fund (€12 billion) of the state", Ricardo Salgado said. (Source: Expresso) 2013 • JUL 26: BES reports worse than expected losses for the 1st half of the year and says it’s considering buying Swiss bank BSI. • NOV 21: BES is first Portuguese bank to issue subordinated debt in four years. The 750 million euros sale is billed as sign of confidence in Portugal's recovery. • DEC 12: Wall Street Journal reports that Espírito Santo International (ESI), sold more than 6 billion euros of debt to one of its own investment funds in a 21 month period from 2011. Newspaper also says that Espírito Santo Financial Group 2012 accounts value its stake in BES at more than four times its 365 million euros market value. • END 2013: Angola government gives a guarantee for 4.2 billion euros of lending (or 70 percent of the total loan book) of BES Angola after the Bank of Portugal became concerned about the exposures. Development is not made public. 2014 • EARLY 2014: Bank of Portugal hires auditors KPMG to carry out "a special purpose limited review" into ESI's third quarter and full year results for 2013. -

Corporate Governance the Case of Banco Espirito Santo

Corporate Governance the case of Banco Espirito Santo ABSTRACT This is a comprehensive case study of the collapse of BES that failed in 2014 and prompted the government to draft and implement a resolution plan for BES in which they created NOVO Banco, a bridge bank to transfer all the healthy operations of the bank and left the toxic assets in BES to be liquidated. BES collapsed after 145 years of existence after it founded by Jose Maria do Espírito Santo e Silva, who started in Lisbon in 1869 as a moneychanger. This study aims to study the causes of the collapse of BES and discuss the corporate governance mechanism that has gone wrong. This study also examines the evidence of clan culture in BES which is probably one of the core strength of the BES and the ES family that helped the bank to survive 145 years, both world wars, dictatorship regimes and nationalisation. The case of BES gives the opportunity to understand that corporate governance rules and recommendations are just as relevant in family businesses as they are in other businesses. Our study found that the desire to diversify the operations of the ES family by investing into many business sectors through its non-financial companies, combined with the economic recession put significant pressure on Ricardo Salgado, who with his status in the family and his power on the board of directors of BES used fraudulent financial reporting and related parties transactions to hide the bank’s toxic assets made mainly of debt instruments of its holding parent. -

Recovery Fund: the Engine Behind the European Transformation

RECOVERY FUND: THE ENGINE BEHIND THE EUROPEAN TRANSFORMATION SPECIAL REPORT | MAY - JUNE 2021 https://eurac.tv/9ThZ With the support of RECOVERY FUND: THE ENGINE BEHIND THE EUROPEAN TRANSFORMATION SPECIAL REPORT https://eurac.tv/9ThZ The unprecedented Recovery and Resilience Facility, the main instrument of the EU’s €800 billion recovery fund, represents a unique opportunity to overcome the recession triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic and complete the twin green and digital transitions of the European economies. But the European Commission, international institu- tions, and experts agree that for this to work, member states must put forward well-designed investment proposals, ambitious reforms and solid governance systems. Contents EU recovery fund struggles to find its true nature 4 Pressure mounts on member states to ensure successful roll- out of recovery fund 6 National authorities take center stage in fight against fraud 8 with recovery funds The new kid on the EU bond block 10 Portugal investors demand bank bond money back or will 12 boycott European fund Thinking about investing in Portugal? Think again. 14 The truth behind BES and Novo Banco! 16 4 RECOVERY FUND SPECIAL REPORT | EURACTIV EU recovery fund struggles to find its true nature By Jorge Valero | EURACTIV.com French president Emmanuel Marcon and chancellor Angela Merkel and EU High Representative, Josep Borrell, during the special European Council summit of July 2020 when the recovery fund was agreed. mid doubts around the concerns among investors and has been dwarfed by the never-ending implementation of the criticism in national capitals. impetus of the Biden Administration, A€800 billion recovery fund, who have already put forward the fifth European Commission and experts “We have lost too much time. -

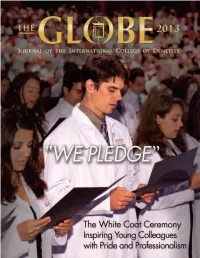

2013 Globe (11.6MB PDF)

Experience CAMLOG live! www.camlog.com 3. Alternatively with platform-switching Excellent Tube-in-Tube™ connection High radial position precision Fast, secure positioning through three grooves and cams Template-guided implantation as an option Millionfold proven SCREW-LINE outer geometry 3 SUCCESS The CAMLOG® Implant System has been a genuine success story since 1999. Its outstanding user-friendliness, first-rate precision, and coherent prosthetic orientation have convinced more and more users. Rounding off its overall offer with an exceptional price-performance ratio, CAMLOG has become the trusted supplier of choice for numerous implant professionals. Go and see for yourself: www.camlog.com CAMLOG stands for success. Experience CAMLOG live! www.camlog.com Alternatively with platform-switching Excellent Tube-in-Tube™ connection High radial position precision Fast, secure positioning through three grooves and cams Template-guided implantation as an option Millionfold proven SCREW-LINE outer geometry SUCCESS The CAMLOG® Implant System has been a genuine success story since 1999. Its outstanding user-friendliness, first-rate precision, and coherent prosthetic orientation have convinced more and more users. Rounding off its overall offer with an exceptional price-performance ratio, CAMLOG has become the trusted supplier of choice for numerous implant professionals. Go and see for yourself: www.camlog.com CAMLOG stands for success. MOTTO Recognizing Service and the Opportunity to Serve MISSION STATEMENT EDITOR The International College of Dentists is a leading honorary S. Dov Sydney, DDS FICD dental organization dedicated to the recognition of outstanding professional achievement and meritorious service and the EDITORIAL ASSISTANTS continued progress of dentistry for the benefit of all humankind. -

The Billion-Dollar Fall of the House of Espirito Santo Was There Unlawful Activity Behind the Spectacular Collapse of the Espirito Santo Empire?

PORTUGAL UNDER PRESSURE: Ricardo Salgado, here at a news conference in early 2012, led the family empire for decades. REUTERS/JOSE MANUEL RIBEIRO The billion-dollar fall of the house of Espirito Santo Was there unlawful activity behind the spectacular collapse of the Espirito Santo empire? BY SERGIO GONCALVES, LAURA NOONAN, ANDREI KHALIP SPECIAL REPORT 1 PORTUGAL BILLION-DOLLAR MELTDOWN CLEAN UP: Banco Espirito Santo had grown to become the second biggest lender in Portugal. REUTERS/HUGO CORREIA LISBON, AUGUST 29, 2014 directive from Portugal’s central bank that The two letters, whose existence was Salgado stop mixing the lender’s affairs made public last month but whose de- n June 9, with his 150-year-old with the family business. The guarantees tails are revealed here for the first time, Portuguese corporate dynasty were also not recorded in the bank’s ac- are a key part of an investigation into the Oclose to collapse, patriarch Ricardo counts at the time, which is required by spectacular fall of one of Europe’s most Espirito Santo Salgado made a desperate Portuguese law. prominent family businesses. Portuguese attempt to save it. The following week, after intense pres- regulators and prosecutors are examining Salgado signed two letters to Venezuela’s sure from regulators, Salgado resigned. them along with the bank’s accounts and state oil company, which had bought $365 Within a month, the holding company, other evidence to determine whether there million in bonds from his family’s hold- Espirito Santo International, filed for was unlawful activity behind the fall of the ing company. -

The Good, the Bad and the Ugly: the Fall and Resolution of Banco Espírito Santo

Case discussion The Good, the Bad and the Ugly: The fall and resolution of Banco Espírito Santo “We usually say that first comes the interest of our country, second, that of the institution and, only in third, that of shareholders” – Ricardo Espírito Santo Silva Salgado, CEO 1992-2014i Ona hot Sunday night,August 3rd, the Portuguese central bank, Banco de Portugal (BdP), announced the resolution of BancoEspírito Santo (BES), which had fallen in disgrace after, a few days earlier, posting a €3.6bn loss in 2014Q2. The size of the losses consumed most of the existing capital base. Once the European Central Bank (ECB) made the decision to revoke BES's status as a counterparty for refinancing operations and requested that the bank paid back about €10 billion in ECB loans, BdP was forced to recognise BES' inability to make such repayment and put the bank under resolution. The resolutioninvolved the separation of BES between a good and a bad bank. BES’ sound assets and most liabilities were transferred toa “transition bank”, or "good bank", which got fresh capital in the amount of €4.9bn from the Portuguese "Bank Resolution Fund". The century and half old BES was to be liquidated, keeping only those assets deemed “toxic” in its balance sheet. This "bad bank" also retained all liabilities to qualified shareholders, the bank's initial equity as well as BES' subordinated bonds. These were ugly news for those who had invested on thatsummer's BES rights issue. Or even those, including Goldman Sachs, who took long positions on the stock a few days before. -

The Good, the Bad and the Ugly the Fall and Resolution of Banco Espírito Santo

A Work Project presented as part of the requirements for the award of a Master’s Degree in Finance from the NOVA School of Business and Economics The Good, the Bad and the Ugly The fall and resolution of Banco Espírito Santo Luís Pedro Rodrigues Teles de Belo Morais no. 747 A Project carried out under the supervision of Prof. Paulo Soares de Pinho 7th January 2014 Abstract This case study – and accompanying teaching note – briefly describes the history of the Espírito Santo family, a banking dynasty who led one of Portugal’s leading economic and financial groups, along with its “crown jewel”, Banco Espírito Santo. It chronicles how the corporate governance issues at BES allowed the family to exploit the bank, its shareholders and its customers, so as to support its unprofitable non-financial businesses. This left the bank in a poor financial situation, which deteriorated beyond control, leaving regulators – whose actions are also analysed here – with no alternative, amidst a severe liquidity crisis, but to apply a resolution measure, pinning large losses on junior bondholders and shareholders before recapitalising the bank. Keywords: Corporate governance; bank regulation; bank resolution ii Contents Abstract ............................................................................................................................. ii Case discussion ................................................................................................................. 1 Espírito Santo: the origins ............................................................................. -

Banco Espirito Santo, S.A. BES Finance Ltd

PROSPECTUS Banco Espirito Santo, S.A. (Incorporated with limited liability in Portugal) (acting through its head office or its Madeira Free Trade Zone branch or its Cayman Islands branch or its London branch) and BES Finance Ltd. (Incorporated with limited liability in the Cayman Islands) unconditionally and irrevocably guaranteed by Banco Espirito Santo, S.A. (Incorporated with limited liability in Portugal) (acting through its London branch) €20,000,000,000 EURO MEDIUM TERM NOTE PROGRAMME This Prospectus supersedes the Prospectus dated 18th January, 2008 and any previous Prospectus or offering circular or supplements thereto and is valid for the purpose of the listing of Notes on the Luxembourg Slock Exchange, for a period of one year from the date of publication. Any Notes (as-defined below) Issued under the Programme on or after the dale of this Prospectus are issued subject to the provisions herein. This Prospectus does not affect any Notes already Issued. Under the €20,000,000,000 Euro Medium Term Note Programme (the "Programme"), each of Banco Espfrito Santo, S.A. (the "Bank" or "BES"), acting through its head office or its Madeira Free Trade Zone branch or its Cayman Islands branch or its London branch, and BES Finance Ltd. ("BES Finance" and, together with the Bank in its capacity as an issuer of Notes under the Programme, the "Issuers" and each an "Issuer") may from time to time issue notes (the "Notes", which will include Senior Notes, Dated Subordinated Notes and Undated Subordinated Notes (as such terms are defined below)) denominated in any currency agreed between the Issuer of such Notes (the "relevant Issuer") and the relevant Dealer (as defined below). -

Horasis Brochure 2009 Lisabon Final

Global China Business Meeting 9-11 November 2009, Lisbon, Portugal a Horasis-leadership event Co-hosts: Aicep,Turismo de Portugal, Caixa Geral de Depósitos Co-organizers: 2005 Committee Center for China and Globalization China CEO Roundtable China Entrepreneur Club e-China Edeluc World Eminence Chinese Business Association Horasis is a global visions community committed to enact visions for a sustainable future (http:/www.horasis.org) Global China Business Meeting 9-11 November 2009, Lisbon, Portugal a Horasis-leadership event Co-hosts: Aicep,Turismo de Portugal, Caixa Geral de Depósitos Co-organizers: 2005 Committee,Center for China and Globalization,China CEO Roundtable, China Entrepreneur Club,e-China, Edeluc,World Eminence Chinese Business Association Co-chairs: Samir Brikho Chief Executive Officer,Amec, United Kingdom Ronnie C. Chan Chairman, Hang Lung Properties, Hong Kong SAR Chen Ping Chairman,TideTime Group, China Feng Jun Chairman,Aigo, China Amadou Hott Chief Executive Officer, UBA Capital, Nigeria Kola Karim Chief Executive Officer, Shoreline Energy Intern., Nigeria David K.P. Li Chairman, Bank of East Asia, Hong Kong SAR Munir Majid Chairman, Malaysia Airlines, Malaysia John M. Neill Group Chief Executive Officer, Unipart Group,United Kingdom Fernando Faria de Oliveira Chairman, Caixa Geral de Depósitos, Portugal Ricardo Salgado Chairman, Banco Espírito Santo, Portugal AlessandroTeixeira President, APEX, Brazil BrunoWu Chairman, Redrock Capital Group Holdings, China WuYing President, CTC Capital, China Zhou Chenjian President, Metersbonwe Group, China Levin Zhu Chief Executive Officer, CICC, China Strategic Partner: Knowledge Partners: Baker & McKenzie Accenture Banco Espírito Santo Media Partners: CEIBS/IESE Caijing Magazine Egon Zehnder International China Daily Government of Macau Global Asia Havas Media International HeraldTribune KPMG WirtschaftsWoche Roland Berger Sino Private Aviation 1 Welcome I warmly welcome you to 5th Horasis Global China Business Meeting and sincerely hope that you will enjoy the discussions.