Nest-Site Fidelity and Cavity Reoccupation by Blue-Fronted

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Foreign Bird Federation Register of Birds Bred in the UK Under Controlled Conditions for the Years 2005 - 2008

ISSN 1352 - 838X The Foreign Bird Federation REGISTER OF BIRDS BRED IN THE UK UNDER CONTROLLED CONDITIONS FOR THE YEARS 2005 - 2008 Front Cover Red Lory Swift Parrakeet Eos bornea Lathamus discolor Yellow-faced Parrotlets Forpus xanthops Fischer’s Lovebird Red-flanked Lorikeet Agapornis fischeri Charmosyna placentis Rear Cover Diamond Doves Pallas’ Rosefinch Geopelia cuneata Carpodacus roseus Java Sparrow Padda oryzivora Gouldian Finch Sydney Waxbill Chloebia gouldiae or Red-browed Finch Aeginthus temporalis Cover Photography © Dennis Avon Foreign Bird Federation Register of Birds Bred in the United Kingdom under Controlled Conditions for the Years 2005 - 2008 Foreign Bird Federation Register of Birds Bred in the UnitedTHE Kingdom FOREIGN under BIRDControlled FEDERATION Conditions for BREEDING the Years 2005 REGISTER - 2008 Foreign Bird Federation Register of Birds Bred in the United Kingdom under Controlled Conditions for the YearsThe FOREIGN 2005 - 2008 BIRD Foreign FEDERATION Bird Federation (FBF) REGISTER Register OF of BIRDSBirds Bred BRED in IN the United KingdomTHE under UK ControlledUNDER CONTROLLED Conditions for CONDITIONS the Years 2005 FOR - 2008 THE Foreign YEARS Bird 2005- Federation 2008 lists, from information volunteered by individual bird owners, avicultural Registerorganisations of Birds Bred and inpublic the Unitedcollections Kingdom alike, close under to 50,000 Controlled breedings Conditions of almost for950 the Years 2005 - foreign2008 Foreignspecies in Birdrecent Federation years. Register of Birds Bred in the -

Special Scientific Report--Wildlife

BOSTON PUBLIC LIBRARY 3 9999 06317 694 3 birds imported /W into the united states in 1970 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR FISH AND WILDLIFE SERVICE BUREAU OF SPORT FISHERIES AND WILDLIFE Special Scientific Report—Wildlife No. 164 DEPOSITORY UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR, ROGERS C. B. MORTON, SECRETARY Nathaniel P. Reed, Assistant Secretary for Fish and Wildlife and Parks Fish and Wildlife Service Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife, Spencer H. Smith, Director BIRDS IMPORTED INTO THE UNITED STATES IN 1970 By Roger B. Clapp and Richard C. Banks Bird and Mammal Laboratories Division of Wildlife Research Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife Special Scientific Report —Wildlife No. 164 Washington, D.C. February 1973 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402-Price $1.25 domestic postpaid, or $1 GPO Bookstore Stock Number 2410-00345 ABSTRACT Birds imported into the United States in 1970 are tabulated by species and the numbers are compared to those for 1968 and 1969. The accuracy of this report is believed to be substantially greater than for the previous years. The number of birds imported in 1970 increased by about 45 percent over 1969, but much of that increase results from more extensive declarations of domestic canaries. Importation of birds other than canaries increased by about 11 percent, with more than half of that increase accounted for by psittacine birds. More than 937,000 individuals of 745 species were imported in 1970. This report tallies imported birds by the country of origin. Eleven nations account for over 95 percent of all birds imported. -

Amazon Parrot

March 2013 SSqquuaawwkk TTaallkk Inside this Issue 1.Stolen Birds Bird of the Month: Amazons 2 Lost Bird Alert 3 Botanical Gardens 4 General Meeting Minutes 5 Board Meeting Minutes 6 Ads and Sponsors 7 The Coastal Bend Companion Bird Club and Rescue Mission seek to promote an interest in companion birds through communication with and education of pet owners, breeders and the general public. In addition, the CBCBC&RM strives to promote the welfare of all birds by CBCBC&RM providing monetary donations for the rescue and rehabilitation of wild birds and by placing abused, abandoned, lost or displaced companion birds in foster care until permanent adoptive homes can be found. Stolen Birds Dianna Wray • • Anyone who has information about the Originally published March 7, 2013 birds is asked to call 361-573-3836 or go at 8:21 p.m., updated March 8, 2013 to Earthworks, 102 E. Airline Road. Ask at 2 p.m. for Laurie Garretson. Mattie, the red-tailed African gray parrot, always greeted Laurie Garretson when she walked into Earthworks Nursery. Monday morning, there was no call of "hello" from Mattie. Her cage was empty, and the cage that held Gilbert, a green Mexican parrot, was gone. "They're a part of our family," Garretson said. "It just makes me sick that people can do things like this." The back door of the nursery was broken open, and two of Garretson's birds, Mattie REWARD and Gilbert, were gone. • A reward is being offered for any information leading to the return of Mattie, Garretson and her husband, Mark a red-tailed African gray parrot, and Garretson, started taking in birds more than Gilbert, a green Mexican parrot. -

Avian Medicine (Avian Science, Technology and Practice) [Samad MA (2013)

LEP Publication No. 13 Avian Medicine (Avian Science, Technology and Practice) [Samad MA (2013). Avian Medicine] 1st Published as: Poultry Science and Medicine: February 2005 2nd Edition as: Avian Medicine: January 2013 ISSN 984-8094-01-1 Language: English Published by: M. Bulbul, Mymensingh, Bangladesh Printed at: Bikash Mudran, 56/5, Fakirepool Bazar, Motijheel, Dhaka-1000, Bangladesh Total pages (9.5 x 7): 1374 Price BDT: 950.0 / copy and US $ 20.0 / copy Stock: Available with limited stock 1 Avian Medicine [2nd Edition: January 2013] PREFACE Bismillahir Rahmanir Raheem I’m pleased to present the 2nd edition of ‘Avian Medicine’ about seven years since the first ‘Poultry Science and Medicine’ was published in 2005. For this edition, significant changes were needed to keep up-to-date with the increasingly rapid expansion of knowledge about the Avian science, technology and practices. The main role of Poultry Vets is to minimize the cost of poultry production and ensure that its products are safe for human consumption. Veterinarians have a major responsibility to ensure that the meat and eggs produced by the poultry under their care are free from pathogens, chemicals, anti-microbial and other drugs that may be harmful to humans. The Veterinary Medical students and Avian Vets must become knowledge about various aspects of birds, especially disease and management associated with impaired production. Such Avian Vets will become specialists who can provide totally integrated avian health and management advice either to the poultry, pet, zoo or wild birds. To be able to do this Avian Vets will need to understand courses on ‘Avian Medicine’ and develop the expertise on their own by diligent self-education in Avian Vet practice. -

University of Groningen Spectral Tuning of Amazon Parrot Feather Coloration by Psittacofulvin Pigments and Spongy Structures

University of Groningen Spectral tuning of Amazon parrot feather coloration by psittacofulvin pigments and spongy structures Tinbergen, Jan; Wilts, Bodo D.; Stavenga, Doekele G. Published in: Journal of Experimental Biology DOI: 10.1242/jeb.091561 IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 2013 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): Tinbergen, J., Wilts, B. D., & Stavenga, D. G. (2013). Spectral tuning of Amazon parrot feather coloration by psittacofulvin pigments and spongy structures. Journal of Experimental Biology, 216(23), 4358-4364. https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.091561 Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to 10 maximum. Download date: 24-09-2021 4358 The Journal of Experimental Biology 216, 4358-4364 © 2013. Published by The Company of Biologists Ltd doi:10.1242/jeb.091561 RESEARCH ARTICLE Spectral tuning of Amazon parrot feather coloration by psittacofulvin pigments and spongy structures Jan Tinbergen*, Bodo D. -

2007 Inventory of Exotic (Non-Native) Bird Species Known to Be in Australia

2007 Inventory of Exotic (non-native) Bird Species known to be in Australia High Interest Species – Class 1 Common Name Scientific Name Additional Scientific names Common Names as recorded on 2003 Inventory of exotic birds known to be in Australia* Antipodes Green Cyanoramphus Antipodes Parakeet, Cyanoramphus Parakeet unicolor Antipodes Island unicolor Parakeet, Antipodes Unicolor Parakeet, Uniform Parakeet Barred Parakeet Bolborhynchus Lineolated Parakeet, Bolborhynchus lineola Banded Parakeet lineola Black Francolin Francolinus Black Partridge Francolinus francolinus francolinus Black Lory Chalcopsitta atra Red-quilled Lory; Chalcopsitta atra Rajah Lory (C. a. Chalcopsitta atra insignis) x Trichoglossus haemotodus Black-capped Pyrrhura Black-capped Pyrrhura Conure rupicola Parakeet, Rock rupicola Conure Black-capped Lorius lory Western Black- Lorius lory Lory capped Lory, Tricoloured Lory Black-capped Pionites Black-headed Pionites Parrot melanocephala Parrot, Black- melanocephala capped Caique, Black-headed Caique; Pallid Caique (P. m. pallida) Black-cheeked Agapornis Black-faced Agapornis Lovebird nigrigenis Lovebird nigrigenis Black-winged Eos cyanogenia Biak Red Lory, Eos cyanogenia Lory Blue-cheeked Lory Blossom-headed Psittacula roseata Psittacula Parakeet roseata Blue-and-yellow Ara ararauna Blue-and-gold Ara ararauna Macaw Macaw, Yellow- Ara ararauna x breasted Macaw, Ara chloropterus Blue Macaw Blue-crowned Aratinga Blue-crowned Aratinga Conure acuticaudata Parakeet, Sharp- acuticaudata tailed Conure Blue-crowned Loriculus Malay -

BEAKS and FEATHERS Page 7

SPECIAL POINTS OF INTEREST: Beaks and This Quarter’s Adoptions Pg. 1 Letter from the Director Feathers Pg. 2 Volunteer of the Month Pg. 2 NEWSLETTER 4RTH QUARTER 2012 JANUARY 1, 2013 Upcoming Events and Vol- unteer Opportunities Pg. 3 This Quarter’s Adoptions Featured FPR Veterinarian Florida Parrot Rescue has (Orange Winged Amazon & Yel- Clinic of the Quarter: Lake adopted 207 animals for 2012 as low Naped Amazon Bonded Howell Animal Clinic of December 31! With over 100 Pair); Boo Boo (Lesser Sulfur birds in rescue at this time, we Crested Cockatoo); Captain Pg. 4 need to keep up this momentum (Quaker Parrot); Captain Jack A Thank you to our Florida and continue to spread the (Nanday Conure); Charlay word to our families, friends, co- (Green Cheek Conure); Chewey Parrot Rescue Volunteers workers and anyone else you (Quaker Parrot); Coco (African Pg. 4 can think of. Keep in mind we Grey); Cody (Goffins Cockatoo); always need new fosters as well. Corey (B&G Macaw); Corona The Vet Chirps In: Egg Gizmo & Mango - Sun Conure We have approximately 15 birds (B&G Macaw); Danny (Eclectus); & Yellow Naped Amazon Laying Problems on the waiting list needing to Destiny (Moluccan Cockatoo); bonded pair By Dr. Orlando Diaz- come into rescue at the mo- Emmitt (Shihtzu); Fluffy (Umbrella Figueroa ment, and we have recently had Cockatoo); Gator (Cockatiel); Pg. 5 to close intake due to limited Gizmo & Mango (Yellow Naped room in foster homes. Amazon and Sun Conure bonded Healthy food choices for pair); Harley (Umbrella Cocka- Lucy your Parrot! Remember that our foster/ too); Jasper (Black Headed Cai- Blue & By Michelle Magnon adoption application is available que); Katie (Eclectus); Louey Gold Pg. -

2007 Inventory of Exotic (Non-Native) Bird Species Known to Be in Australia

2007 Inventory of Exotic (non-native) Bird Species known to be in Australia High Interest Species – Class 1 Scientific Name Common Name Additional Common Names Scientific names as recorded on 2003 Inventory of exotic birds known to be in Australia* Agapornis Black-cheeked Black-faced Lovebird Agapornis nigrigenis Lovebird nigrigenis Aix sponsa Carolina Duck Wood Duck Aix sponsa Alisterus Moluccan King- Ambon King-parrot, Ambon Alisterus amboinensis parrot Parrot, Amboina King-parrot, amboinensis Amboina Parrot, Island King- parrot, Red Parakeet; Salawati King-parrot (A. a. dorsalis) Amazona aestiva Blue-fronted Blue-fronted Parrot, Amazona aestiva Amazon Turquoise-fronted Amazon, Turquoise-fronted Parrot; Yellow-winged Amazon (A. a xanthopteryx) Amazona albifrons White-fronted White-fronted Parrot, Amazona albifrons Amazon Spectacled Amazon, Spectacled Parrot, White- browed Amazon, White- browed Parrot Amazona amazonica Orange-winged Orange-winged Parrot Amazona Amazon amazonica Amazona autumnalis Red-lored Amazon Red-lored Parrot, Yellow- Amazona cheeked Amazon, Yellow- autumnalis cheeked Parrot, Scarlet-lored Amazon, Scarlet-lored Parrot, Red-fronted Amazon, Red-fronted Parrot, Golden- cheeked Amazon, Golden- cheeked Parrot; Salvin's Amazon, Salvin's Parrot (A. a. salvinii); Lilacine Amazon, Lilacine Parrot, Lesson's Amazon, Lesson's Parrot (A. a. lilacina) Amazona finschi Lilac-crowned Lilac-crowned Parrot, Amazona finschi Amazon Finsch's Parrot, Pacific Parrot; Wood's Red-fronted Parrot (A. f. woodi) Amazona Cuban Amazon Cuban Parrot, Rose-throated Amazona leucocephala Amazon, Rose-throated leucocephala Parrot, White-headed Amazon, White-headed Parrot, Caribbean Amazon, Caribbean Parrot; Bahamas Amazon, Bahamas Parrot (A. l. bahamensis); Grand Cayman Amazon, Grand Cayman Parrot (A. l. caymanensis); Cayman Brac Amazon, Cayman Brac Parrot (A. -

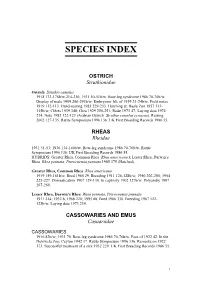

Species Index

SPECIES INDEX OSTRICH Struthionidae Ostrich Struthio camelus 1918 173-176b/w,214-216; 1931 50-51b/w. Bow-leg syndrome 1986 70-76b/w. Display of male 1909 286-291b/w. Embryonic life of 1919 21-24b/w. Field notes 1919 112-113. Hand-rearing 1983 229-233. Hatching at: Basle Zoo 1957 113- 115b/w; Clères 1939 348; Giza 1929 250-251; Rode 1973 47. Laying data 1974 234. Note 1982 122-123 (Arabian Ostrich Struthio camelus syriacus). Raising 2002 127-135. Ratite Symposium 1996 136. UK First Breeding Records 1986 55. RHEAS Rheidae 1931 51-53; 1936 134-140b/w. Bow-leg syndrome 1986 70-76b/w. Ratite Symposium 1996 136. UK First Breeding Records 1986 55. HYBRIDS: Greater Rhea, Common Rhea Rhea americana x Lesser Rhea, Darwin’s Rhea Rhea pennata, Pterocnemia pennata 1905 375 (Hatched). Greater Rhea, Common Rhea Rhea americana 1919 159-161b/w. Bred 1965 29. Breeding 1911 126-128b/w; 1950 202-205; 1954 225-227. Domestication 1907 129-130. In captivity 1902 127b/w. Polyandry 1907 267-269. Lesser Rhea, Darwin’s Rhea Rhea pennata, Pterocnemia pennata 1911 214; 1932 6; 1968 220; 1995 88. Bred 1906 330. Breeding 1967 122- 123b/w. Laying data 1973 234. CASSOWARIES AND EMUS Casuariidae CASSOWARIES 1916 82b/w; 1931 70. Bow-leg syndrome 1986 70-76b/w. Foot of 1932 42. In the Dehiwela Zoo, Ceylon 1942 1*. Ratite Symposium 1996 136. Remarks on 1922 173. Successful treatment of a sick 1932 229. UK First Breeding Records 1986 55. 1 Southern Cassowary, Double-wattled Cassowary Casuarius casuarius Bred 1986 196; 1993 218; 1998 44. -

Androglossini Species Tree

Androglossini Red-capped Parrot / Pileated Parrot, Pionopsitta pileata Blue-bellied Parrot, Triclaria malachitacea Black-winged Parrot, Hapalopsittaca melanotis Rusty-faced Parrot, Hapalopsittaca amazonina Indigo-winged Parrot / Fuertes’s Parrot, Hapalopsittaca fuertesi Red-faced Parrot, Hapalopsittaca pyrrhops Brown-hooded Parrot, Pyrilia haematotis Rose-faced Parrot, Pyrilia pulchra Saffron-headed Parrot, Pyrilia pyrilia Orange-cheeked Parrot, Pyrilia barrabandi Caica Parrot, Pyrilia caica Bald Parrot, Pyrilia aurantiocephala Vulturine Parrot, Pyrilia vulturina Short-tailed Parrot, Graydidascalus brachyurus Yellow-faced Parrot, Alipiopsitta xanthops Dusky Parrot, Pionus fuscus Red-billed Parrot, Pionus sordidus Scaly-headed Parrot, Pionus maximiliani White-capped Parrot, Pionus seniloides Plum-crowned Parrot, Pionus tumultuosus Blue-headed Parrot, Pionus menstruus White-crowned Parrot, Pionus senilis Bronze-winged Parrot, Pionus chalcopterus White-fronted Amazon, Amazona albifrons ?Yellow-lored Parrot / Yucatan Amazon, Amazona xantholora Black-billed Amazon, Amazona agilis Yellow-billed Amazon, Amazona collaria Cuban Amazon, Amazona leucocephala Hispaniolan Amazon, Amazona ventralis Puerto Rican Amazon, Amazona vittata Festive Amazon, Amazona festiva Vinaceous-breasted Amazon, Amazona vinacea Tucuman Amazon, Amazona tucumana Red-spectacled Amazon, Amazona pretrei Imperial Amazon, Amazona imperialis Red-tailed Amazon, Amazona brasiliensis Orange-winged Amazon, Amazona amazonica St. Vincent Amazon, Amazona guildingii Red-crowned Amazon, -

The First Captive B Eeding of the Hoffman's Conure by Chris Rowley

The First Captive B eeding of the Hoffman's Conure by Chris Rowley Hoffman's conures range from southern Costa Rica to northern Panama. The nominate race (pyrrhura ho1fmanniho1fmannVisconfinedto Costa Rica, and P. h. gaudens is restricted to Panama. The subject of this paper shall be the first breeding of the sub-species P. h. gaudens. The breeding stock was acquired in Panama by Dr. athan B. Gale in 1980. The first two Hoffman's conures raised in captivity. I received thepair inquestioninearly 1981 and had them surgically sexed. In were removed andfound tobe infertile. maize, 5% whole corn, 5% oat groats, May the weather was cool with highs in In 1982 the male was seenfeeding the and 5% dried peas. In addition to the the upper60s andrainy. May 5, 1981 the hen in early February. Copulation was mix and a variety of greens, the birds hen laid her first egg and three more observed starting mid-February and by were fed apples and otherfresh fruits in followed. The eggs were laid in a the end of the month the time spent season including peaches, mulberries, plywood nestbox that measured mating increased in length from less pomegranates, tangerines, and pyra 18"x9"x9", with three inches of than a minute up to 15 minutes. By this cantha berries. No other supplements material in the bottom. The boxes are time thehenfrequently enteredthe nest were added to food orwater. Bothfood checked periodically, often twice a day box for short periods. and water are offered in 8" crocks. in the breeding season. The hen began The eggs were laid on March 5, 7, 9, A baby was seen peering out of the sitting immediately and was very 11, 13, and 15 totalling six eggs.