Noisy Fields: Interference and Equivocality in the Sonic Legacies of Information Theory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DAIRY MART and Gone to Sleep in Defeat

TUESDAY, JUNE 4, 1968 t - PAGE TWENTY-POUR Average Daily Net Frees Run HmtrlifHtfr lEoftting fipraU) fVtr T lu Week Ended The Weather Jane 1, 1N8 Card Party Set Fair tonight. Low 60 to 60. About Town iianrlfFfitFr lEuming Sunny and warm tomorrow. I 15,055 First Ohurch of Christ, To Benefit FISH High In upper 80s. HaneheMter-—A City o f ViOage Chmrm SolenttiA M^Il have its regular The Consultation of Church testimony mooting tomorrow at Union (COCU) committee is VOL. LXXXVn, NO. 209 (THIRTT-SIX PAGES—TWO SECTIONS) 8 ip.m. at the church. MANCHESTER, CONN., WEDNESDAY. JUNE 6, 1968 (OlMelfled AdvertWng on F^ie S3) PRICE TEN CENTS sponsoring a card party Thurs A mU-<week Bible study will day, June 20, at 8 p.m. at Sec be conducted tomorrow at 7:80 ond Congregational Church. pm., at ’PrinVty Covenant Proceeds will be used to aid in Church. the establishment of FISH, an interdenominational service or The Master Mason degree ganization, in Manchester. win be conferred at a meeting FISH is being organized !n of Uriel Lodge of Masons Sat Manchester to help those in urday at 7:30 p.in. at the Ma need during an illness or an sonic Temple, Merrow. A roaat emergency. Donations are need beef dinner will be served at RFK Critical After Shooting ed if the program is to be put 0:30. Officers will r^earse for in operation by July 1 as the degree work Friday at 7:30 GLASS INSTALLED p.m. at the Mlasonic Temple. -

Issue 148.Pmd

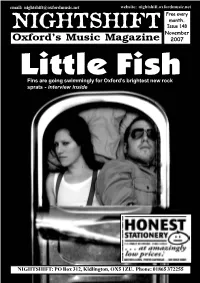

email: [email protected] website: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Free every month. NIGHTSHIFT Issue 148 November Oxford’s Music Magazine 2007 Little Fish Fins are going swimmingly for Oxford’s brightest new rock sprats - interview inside NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWNEWSS Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] AS HAS BEEN WIDELY Oxford, with sold-out shows by the REPORTED, RADIOHEAD likes of Witches, Half Rabbits and a released their new album, `In special Selectasound show at the Rainbows’ as a download-only Bullingdon featuring Jaberwok and album last month with fans able to Mr Shaodow. The Castle show, pay what they wanted for the entitled ‘The Small World Party’, abum. With virtually no advance organised by local Oxjam co- press or interviews to promote the ordinator Kevin Jenkins, starts at album, `In Rainbows’ was reported midday with a set from Sol Samba to have sold over 1,500,000 copies as well as buskers and street CSS return to Oxford on Tuesday 11th December with a show at the in its first week. performers. In the afternoon there is Oxford Academy, as part of a short UK tour. The Brazilian elctro-pop Nightshift readers might remember a fashion show and auction featuring stars are joined by the wonderful Metronomy (recent support to Foals) that in March this year local act clothes from Oxfam shops, with the and Joe Lean and the Jing Jang Jong. Tickets are on sale now, priced The Sad Song Co. - the prog-rock main concert at 7pm featuring sets £15, from 0844 477 2000 or online from wegottickets.com solo project of Dive Dive drummer from Cyberscribes, Mr Shaodow, Nigel Powell - offered a similar deal Brickwork Lizards and more. -

CCRMA Fall Concert 2013

Romain Michon is a PhD candidate at CCRMA. After graduating from two bachelors in Musicology and Computer Science in Ireland and in France, he completed a Department of Music Stanford University Masters degree in computer music at the university of Lyon (France). He worked as an engineer in several research center in computer music such as the Institut de Recherche et Coordination Acoustique/Musique (IRCAM), the Groupe de Recherche en Acoustique et en Musique Electronique (GRAME) and the Centre Interdisciplinaire d'Etudes et de Recherches sur l'Expression Contemporaine (CIEREC). Romain’s research interest mainly focuses on digital signal processing, mobile platform and web-technology for music. CCRMA Tim O'Brien is a second year Masters student at CCRMA. His interests include signal processing, progressive rock, and interesting noises. Prior to Stanford, Tim composed and preformed with various bands in New York. He holds a B.S. in physics from the University of Virginia. Fall Concert Rufus Olivier Jr.: a student of David Briedenthal of the Los Angeles Philharmonic. Member, Stanford Woodwind Quintet. Principal bassoonist of the San Francisco Opera Orchestra and S.F. Ballet Orchestra formerly with Los Angeles Philharmonic and San Francisco Symphony. International soloist and recording artist. Teaches at Mills College and Stanford University. Leland C. Smith was born in Oakland, California in 1925. He began composing in 1938 and first studied with Darius Milhaud at age 15. He did some dance band work and then served in a Navy band (and combo) for two and a half years. He studied with Roger Sessions in Berkeley, where he served as his assistant, and received his B.A. -

Garage House Music Whats up with That

Garage House Music whats up with that Future funk is a sample-based advancement of Nu-disco which formed out of the Vaporwave scene and genre in the early 2010s. It tends to be more energetic than vaporwave, including elements of French Home, Synth Funk, and making use of Vaporwave modifying techniques. A style coming from the mid- 2010s, often explained as a blend of UK garage and deep home with other elements and strategies from EDM, popularized in late 2014 into 2015, typically mixes deep/metallic/sax hooks with heavy drops somewhat like the ones discovered in future garage. One of the very first house categories with origins embeded in New York and New Jersey. It was named after the Paradise Garage bar in New york city that operated from 1977 to 1987 under the prominent resident DJ Larry Levan. Garage house established along with Chicago home and the outcome was home music sharing its resemblances, affecting each other. One contrast from Chicago house was that the vocals in garage house drew stronger impacts from gospel. Noteworthy examples consist of Adeva and Tony Humphries. Kristine W is an example of a musician involved with garage house outside the genre's origin of birth. Also understood as G-house, it includes very little 808 and 909 drum machine-driven tracks and often sexually explicit lyrics. See likewise: ghettotech, juke house, footwork. It integrates components of Chicago's ghetto house with electro, Detroit techno, Miami bass and UK garage. It includes four-on-the-floor rhythms and is normally faster than a lot of other dance music categories, at approximately 145 to 160 BPM. -

(At) Miracosta

The Creative Music Recording Magazine Jeff Tweedy Wilco, The Loft, Producing, creating w/ Tom Schick Engineer at The Loft, Sear Sound Spencer Tweedy Playing drums with Mavis Staples & Tweedy Low at The Loft Alan Sparhawk on Jeff’s Production Holly Herndon AI + Choir + Process Ryan Bingham Crazy Heart, Acting, Singing Avedis Kifedjian of Avedis Audio in Behind the Gear Dave Cook King Crimson, Amy Helm, Ravi Shankar Mitch Dane Sputnik Sound, Jars of Clay, Nashville Gear Reviews $5.99 No. 132 Aug/Sept 2019 christy (at) miracosta (dot) edu christy (at) miracosta (dot) edu christy (at) miracosta (dot) edu christy (at) miracosta (dot) edu christy (at) miracosta (dot) edu christy (at) miracosta (dot) edu Hello and welcome to Tape Op 10 Letters 14 Holly Herndon 20 Jeff Tweedy 32 Tom Schick # 40 Spencer Tweedy 44 Gear Reviews ! 66 Larry’s End Rant 132 70 Behind the Gear with Avedis Kifedjian 74 Mitch Dane 77 Dave Cook Extra special thanks to Zoran Orlic for providing more 80 Ryan Bingham amazing photos from The Loft than we could possibly run. Here’s one more of Jeff Tweedy and Nels Cline talking shop. 83 page Bonus Gear Reviews Interview with Jeff starts on page 20. <www.zoranorlic.com> “How do we stay interested in the art of recording?” It’s a question I was considering recently, and I feel fortunate that I remain excited about mixing songs, producing records, running a studio, interviewing recordists, and editing this magazine after twenty-plus years. But how do I keep a positive outlook on something that has consumed a fair chunk of my life, and continues to take up so much of my time? I believe my brain loves the intersection of art, craft, and technology. -

The Madoffization of Society

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE CRS0010.1177/0896920512446760Monaghan and O’FlynnCritical Sociology 4467602012 provided by University of Limerick Institutional Repository Article Critical Sociology 1 –19 The Madoffization of Society: © The Author(s) 2012 Reprints and permission: A Corrosive Process in an Age of sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/0896920512446760 Fictitious Capital crs.sagepub.com Lee F. Monaghan University of Limerick, Ireland Micheal O’Flynn The Open University in Ireland Abstract In 2009, US financier Bernard (Bernie) L. Madoff was jailed for 150 years after pleading guilty to running a massive ponzi scheme. While superficial condemnation was widespread, his US$65 billion fraud cannot be understood apart from the institutions, practices and fictions of contemporary finance capitalism. Madoff’s scam was rooted in the wider political prioritization of accumulation through debt expansion and the deregulated, desupervised and criminogenic environment facilitating it. More generally, global finance capital reproduces many of the core elements of the Madoff scam (i.e. mass deception, secrecy and obfuscation), particularly in neoliberalized Anglophone societies. We call this ‘Madoffization’. We suggest that societies are ‘Madoffized’, not only in the sense of their being subject to the ill-effects of speculative ponzi finance, but also in the sense that their prioritization of accumulation through debt expansion makes fraudulent practices, economic collapse and scapegoating inevitable. Keywords crisis, fictitious capital, financialization, fraud, neoliberalism, political economy Introduction In 2009, Bernard (Bernie) L. Madoff, a US financier, was jailed for 150 years after pleading guilty to running a ponzi scheme where he defrauded billions of dollars from his clients. -

Mediated Music Makers. Constructing Author Images in Popular Music

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Helsingin yliopiston digitaalinen arkisto Laura Ahonen Mediated music makers Constructing author images in popular music Academic dissertation to be publicly discussed, by due permission of the Faculty of Arts at the University of Helsinki in auditorium XII, on the 10th of November, 2007 at 10 o’clock. Laura Ahonen Mediated music makers Constructing author images in popular music Finnish Society for Ethnomusicology Publ. 16. © Laura Ahonen Layout: Tiina Kaarela, Federation of Finnish Learned Societies ISBN 978-952-99945-0-2 (paperback) ISBN 978-952-10-4117-4 (PDF) Finnish Society for Ethnomusicology Publ. 16. ISSN 0785-2746. Contents Acknowledgements. 9 INTRODUCTION – UNRAVELLING MUSICAL AUTHORSHIP. 11 Background – On authorship in popular music. 13 Underlying themes and leading ideas – The author and the work. 15 Theoretical framework – Constructing the image. 17 Specifying the image types – Presented, mediated, compiled. 18 Research material – Media texts and online sources . 22 Methodology – Social constructions and discursive readings. 24 Context and focus – Defining the object of study. 26 Research questions, aims and execution – On the work at hand. 28 I STARRING THE AUTHOR – IN THE SPOTLIGHT AND UNDERGROUND . 31 1. The author effect – Tracking down the source. .32 The author as the point of origin. 32 Authoring identities and celebrity signs. 33 Tracing back the Romantic impact . 35 Leading the way – The case of Björk . 37 Media texts and present-day myths. .39 Pieces of stardom. .40 Single authors with distinct features . 42 Between nature and technology . 45 The taskmaster and her crew. -

The Sculpted Voice an Exploration of Voice in Sound Art

The Sculpted Voice an exploration of voice in sound art Author: Olivia Louvel Institution: Digital Music and Sound Art. University of Brighton, U.K. Supervised by Dr Kersten Glandien 2019. Table of Contents 1- The plastic dimension of voice ................................................................................... 2 2- The spatialisation of voice .......................................................................................... 5 3- The extended voice in performing art ........................................................................16 4- Reclaiming the voice ................................................................................................20 Bibliography ....................................................................................................................22 List of audio-visual materials ............................................................................................26 List of works ....................................................................................................................27 List of figures...................................................................................................................28 Cover image: Barbara Hepworth, Pierced Form, 1931. Photographer Paul Laib ©Witt Library Courtauld Institute of Art London. 1 1- The plastic dimension of voice My practice is built upon a long-standing exploration of the voice, sung and spoken and its manipulation through digital technology. My interest lies in sculpting vocal sounds as a compositional -

April 2021 New Releases

April 2021 New Releases SEE PAGE 15 what’s featured exclusives inside PAGE 3 RUSH Releases Vinyl Available Immediately 79 Music [MUSIC] Vinyl 3 CD 11 ROY ORBISON - HEMINGWAY, A FILM BY JON ANDERSON - FEATURED RELEASES Video THE CAT CALLED DOMINO KEN BURNSAND LYNN OLIAS OF SUNHILLOW: 48 NOVICK. ORIGINAL 2 DISC EXPANDED & Film MUSIC FROM THE PBS REMASTERED DOCUMENTARY Films & Docs 50 MVD Distribution Independent Releases 78 Order Form 81 Deletions & Price Changes 84 THE FINAL COUNTDOWN DONNIE DARKO (UHD) ACTION U.S.A. 800.888.0486 (3-DISC LIMITED 203 Windsor Rd., Pottstown, PA 19464 EDITION/4K UHD+BLU- www.MVDb2b.com RAY+CD) WO FAT - KIM WILSON - SLY & ROBBIE - PSYCHEDELONAUT TAKE ME BACK RED HILLS ROAD DONNIE DARKO SEES THE LIGHT! The 2001 thriller DONNIE DARKO gets the UHD/4K treatment this month from Arrow Video, a 2-disc presentation that shines a crisp light on this star-studded film. Counting PATRICK SWAYZE and DREW BARRYMORE among its luminous cast, this first time on UHD DONNIE DARKO features the film and enough extras to keep you in the Darko for a long time! A lighter shade of dark is offered in the limited-edition steelbook of ELVIRA: MISTRESS OF THE DARK, a horror/comedy starring the horror hostess. Brand new artwork and an eye-popping Hi-Def presentation. Blue Underground rises again in the 4K department, with a Bluray/UHD/CD special of THE FINAL COUNTDOWN. The U.S.S. Nimitz is hurled back into time and can prevent the attack on Pearl Harbor! With this new UHD version, the KIRK DOUGLAS-led crew can see the enemy with crystal clarity! You will not believe your eyes when you witness the Animal Kingdom unleashed with two ‘Jaws with Claws’ horror movies from Severin Films, GRIZZLY and DAY OF THE ANIMALS. -

Nb Artistes Ville Région / Province… Nom De L'événement Création (Ou Manifestatio Nb D'artistes Manifestation De Reprise) N

Année de Mois de la Mois de la Nb artistes Ville Région / Province… Nom de l'événement création (ou manifestatio Nb d'artistes manifestation de reprise) n Festival Afrique du Sud Johannesburg Gauteng Street Art Cinemart 2018 10 Festival Afrique du Sud Johannesburg Gauteng City of Gold Art Festival 2013 10 12 Meeting of Styles South Festival Afrique du Sud Johannesburg Gauteng Africa 2018 4 12 Anfiteatro de Poéticas Festival Argentine Esteban Echeverria Buenos Aeres Urbanas 2019 9 Festival Australie Benalla Victoria Wall to Wall festival 2015 4 23 Festival Australie Bendigo Victoria Paint Jam 8 Festival Australie Brisbane Queensland BSAF 2016 5 115 Nouvelle Galle du Festival Australie Caringbah Sud Walk the Wall Festival 2018 11 40 Festival Australie Darwin Territoire du Nord Darwin Street Art Festival 2017 9 17 Festival Australie Frankston Victoria The big Picture Festival 2018 3 10 Festival Australie Jamestown Australie du Sud Jamestown mural fest 9 18 Festival Australie Melbourne Victoria Can’t do Tomorrow 2020 2 54 Festival Australie partout Stencil Art Prize 2009 x 70 Nouvelle Galle du Festival Australie Port Kembla Sud Wonderwalls Festival 2012 2 10 Festival Australie Rochester Victoria Rochester Mural Festival 2015 2 8 Davies Construction Festival Australie Sheffield Tasmanie International Mural Fest 2003 4 9 Nouvelle Galle du Festival Australie The Entrance Sud Chalk Urban Art 2005 1 Année de Mois de la Mois de la Nb artistes Ville Région / Province… Nom de l'événement création (ou manifestatio Nb d'artistes manifestation de reprise) -

Movies from the 1970S

1 / 2 Movies From The 1970s A look at the Bollywood films that shaped 1970s. Arguably the most influential decade vis-à-vis its impact on India's popular culture, the decade .... Best movies of the 1970s: From Chinatown to Foxy Brown · Badlands (1973) · The Devils (1971) · Moonraker (1979) · Chinatown (1974) · The Wicker .... Vansploitation: Like hot-rod and biker movies of the 1950s and 1960s, the 1970s was the golden age of movies about vans.. Top Ten Sci-Fi Movies of the 1970s ... things happened in the cinema of the seventies, but it was not a great decade for science fiction movies.. Indie movies today show the real Manhattan... like Pi or Girlfight. My favorite NYC 70s movie is Serpico - Al Pacino wears some tough clothes!. I would say 1960's to 1970's, somewhere in that range. Two pivotal films that reinvented the genre of wuxia movie making came out in the late 1960's: King Hu's .... The 140 Essential 1970s Movies. #140. The Last House on the Left (1972) 62% #139. The Towering Inferno (1974) 69% #138. The Tenant (1976) 88% #137. Sholay (1975) 92% #136. Watership Down (1978) 82% #135. Grey Gardens (1975) #134. Salò o le 120 giornate di Sodoma (Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom) (1979) #133. Pink .... Best 70s movies · 1. The Godfather Part II (1974) · 2. Star Wars (1977) · 3. Alien (1979) · 4. One Flew Over The Cuckoo's Nest (1975) · 5. Jaws (1975) · 6. Apocalypse .... '70s kung fu movies are some of the most badass martial arts films of all time due to their fearless actors and fighters. -

Popular Music in Germany the History of Electronic Music in Germany

Course Title Popular Music in Germany The History of Electronic Music in Germany Course Number REMU-UT.9811001 SAMPLE SYLLABUS Instructors’ Contact Information Heiko Hoffmann [email protected] Course Details Wednesdays, 6:15pm to 7:30pm Location of class: NYU Berlin Academic Center, Room “Prenzlauer Berg” (tbc) Prerequisites No pre-requisites Units earned 2 credits Course Description From Karlheinz Stockhausen and Kraftwerk to Giorgio Moroder, D.A.F. and the Euro Dance of Snap!, the first nine weeks of class consider the history of German electronic music prior to the Fall of the Wall in 1989. We will particularly look at how electronic music developed in Germany before the advent of house and techno in the late 1980s. One focus will be on regional scenes, such as the Düsseldorf school of electronic music in the 1970s with music groups such as Cluster, Neu! and Can, the Berlin school of synthesizer pioneers like Tangerine Dream, Klaus Schulze and Manuel Göttsching, or Giorgio Moroder's Sound of Munich. Students will be expected to competently identify key musicians and recordings of this creative period. The second half of the course looks more specifically at the arrival of techno, a new musical movement, and new technology in Berlin and Germany in the turbulent years after the Fall of the Berlin Wall, up to the present. Indeed, Post-Wall East Berlin, full of abandoned spaces and buildings and deserted office blocks, was the perfect breeding ground for the youth culture that would dominate the 1990s and led techno pioneers and artists from the East and the West to take over and set up shop.