The Lasting World: Simon Dinnerstein and the Fulbright Triptych

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oral History Interview with Raphael Soyer, 1981 May 13-June 1

Oral history interview with Raphael Soyer, 1981 May 13-June 1 Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Funding for this interview was provided by the Wyeth Endowment for American Art. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a tape-recorded interview with Raphael Soyer on May 13, 1981. The interview was conducted by Milton Brown for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Interview Tape 1, side A MILTON BROWN: This is an interview with Raphael Soyer with Milton Brown interviewing. Raphael, we’ve known each other for a very long time, and over the years you have written a great deal about your life, and I know you’ve given many interviews. I’m doing this especially because the Archives wants a kind of update. It likes to have important American artists interviewed at intervals, so that as time goes by we keep talking to America’s famous artists over the years. I don’t know that we’ll dig anything new out of your past, but let’s begin at the beginning. See if we can skim over the early years abroad and coming here in general. I’d just like you to reminisce about your early years, your birth, and how you came here. RAPHAEL SOYER: Well, of course I was born in Russia, in the Czarist Russia, and I came here in 1912 when I was twelve years old. -

Faces of the League Portraits from the Permanent Collection

THE ART STUDENTS LEAGUE PRESENTS Faces of the League Portraits from the Permanent Collection Peggy Bacon Laurent Charcoal on paper, 16 ¾” x 13 ¾” Margaret Frances "Peggy" Bacon (b. 1895-d. 1987), an American artist specializing in illustration, painting, and writing. Born in Ridgefield, Connecticut, she began drawing as a toddler (around eighteen months), and by the age of 10 she was writing and illustrating her own books. Bacon studied at the Art Students League from 1915-1920, where her artistic talents truly blossomed under the tutelage of her teacher John Sloan. Artists Reginald Marsh and Alexander Brook (whom she would go on to marry) were part of her artistic circle during her time at the League. Bacon was famous for her humorous caricatures and ironic etchings and drawings of celebrities of the 1920s and 1930s. She both wrote and illustrated many books, and provided artworks for many other people’s publications, in addition to regularly exhibiting her drawings, paintings, prints, and pastels. In addition to her work as a graphic designer, Bacon was a highly accomplished teacher for over thirty years. Her works appeared in numerous magazine publications including Vanity Fair, Mademoiselle, Harper’s Bazaar, Vogue, Dial, the Yale Review, and the New Yorker. Her vast output of work included etchings, lithographs, and her favorite printmaking technique, drypoint. Bacon’s illustrations have been included in more than 64 children books, including The Lionhearted Kitten. Bacon’s prints are in the collections of the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Brooklyn Museum, and the Museum of Modern Art, all in New York. -

Encyklopédia Kresťanského Umenia

Marie Žúborová - Němcová: Encyklopédia kresťanského umenia americká architektúra - pozri chicagská škola, prériová škola, organická architektúra, Queen Anne style v Spojených štátoch, Usonia americká ilustrácia - pozri zlatý vek americkej ilustrácie americká retuš - retuš americká americká ruleta/americké zrnidlo - oceľové ozubené koliesko na zahnutej ose, užívané na zazrnenie plochy kovového štočku; plocha spracovaná do čiarok, pravidelných aj nepravidelných zŕn nedosahuje kvality plochy spracovanej kolískou americká scéna - american scene americké architektky - pozri americkí architekti http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:American_women_architects americké sklo - secesné výrobky z krištáľového skla od Luisa Comforta Tiffaniho, ktoré silno ovplyvnili európsku sklársku produkciu; vyznačujú sa jemnou farebnou škálou a novými tvarmi americké litografky - pozri americkí litografi http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:American_women_printmakers A Anne Appleby Dotty Atti Alicia Austin B Peggy Bacon Belle Baranceanu Santa Barraza Jennifer Bartlett Virginia Berresford Camille Billops Isabel Bishop Lee Bontec Kate Borcherding Hilary Brace C Allie máj "AM" Carpenter Mary Cassatt Vija Celminš Irene Chan Amelia R. Coats Susan Crile D Janet Doubí Erickson Dale DeArmond Margaret Dobson E Ronnie Elliott Maria Epes F Frances Foy Juliette mája Fraser Edith Frohock G Wanda Gag Esther Gentle Heslo AMERICKÁ - AMES Strana 1 z 152 Marie Žúborová - Němcová: Encyklopédia kresťanského umenia Charlotte Gilbertson Anne Goldthwaite Blanche Grambs H Ellen Day -

A Full Biography Including Honors, Awards and Collections

FULL Biography B U R T O N P H I L L I P S I L V E R M A N complete Biography Born 1928, Brooklyn, NY. Education: BA Columbia University. Served AUS 1951-1953 Taught: the School of Visual Arts, NYC 1964-65; Studio Classes, 1971-to present Positions: Member of the Council, the National Academy of Design, 1976-78; 2001-2003, Membership Committee 2003-20051 Member of the Council; American Watercolor Society 1992-94, Board of Advisers. the Portrait Society of America, 1999 to present. Member, the Century Association ,.elect. 2007, AWARDS & HONORSs 2018 G&B Marble Medal, American Watercolor Society Exhibition. NY 2011 Jury's Selection, The Outwin Boochever Portrait Competition, Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery 2008 Berkelson Award, the National Academy Museum 181st Exhibition 2006 Berkelson Award, the National Academy Museum 179th Exhibition 2005 Annual Award for Excellence in the Arts. Newington Cropsey Cultural Center Jury’s Selection, The Outwin Boochever Portrait Competition, Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery, 2004 Dong Kingman Award, The American Watercolor Society Annual, NYC Gold Medal Lifetime Award , National Portrait Society Boston, MA 2002 Honorary Doctorate awarded by the Academy of Art College, San Francisco, CA 1997 Paul and Margaret Berkelson Prize, National Academy of Design, NYC Mario Cooper Award The AWS Annual, NYC 1996 Clara Stroud Memorial, The AWS, NYC 1995 The Silver Medal of Honor, the Annual of the American Watercolor Society, NYC 1994 Clara Stroud Memorial, AWS Annual, NYC 1992 The Joseph Isidor Medal, National Academy of Design Annual, NYC 1991 The High Winds Medal, AWS Annual, NYC Smith Distinguished Visiting Professor, the George Washington University, Wash, DC Elected Hall of Fame, Pastel Society of America 1990 The Catherine Stroud Memorial Award, AWS Annual, NYC 1989 The Mary Pleisner Memorial Award, Aws Annual, NYC 1987 The Mary Pleisner Memorial Award, AWS Annual, NYC 1985 The High Winds Medal, AWS Annual, NYC 1984 The Silver Medal, AWS Annual 1983 Henry W. -

Faces of the League Portraits from the Permanent Collection

THE ART STUDENTS LEAGUE PRESENTS Faces of the League Portraits from the Permanent Collection Peggy Bacon Laurent Charcoal on paper, 16 ¾” x 13 ¾” Margaret Frances "Peggy" Bacon (b. 1895-d. 1987), an American artist specializing in illustration, painting, and writing. Born in Ridgefield, Connecticut, she began drawing as a toddler (around eighteen months), and by the age of 10 she was writing and illustrating her own books. Bacon studied at the Art Students League from 1915-1920, where her artistic talents truly blossomed under the tutelage of her teacher John Sloan. Artists Reginald Marsh and Alexander Brook (whom she would go on to marry) were part of her artistic circle during her time at the League. Bacon was famous for her humorous caricatures and ironic etchings and drawings of celebrities of the 1920s and 1930s. She both wrote and illustrated many books, and provided artworks for many other people’s publications, in addition to regularly exhibiting her drawings, paintings, prints, and pastels. In addition to her work as a graphic designer, Bacon was a highly accomplished teacher for over thirty years. Her works appeared in numerous magazine publications including Vanity Fair, Mademoiselle, Harper’s Bazaar, Vogue, Dial, the Yale Review, and the New Yorker. Her vast output of work included etchings, lithographs, and her favorite printmaking technique, drypoint. Bacon’s illustrations have been included in more than 64 children books, including The Lionhearted Kitten. Bacon’s prints are in the collections of the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Brooklyn Museum, and the Museum of Modern Art, all in New York. -

Artists' Fellowship, Inc

October 2020 ARTISTS’ FELLOWSHIP, INC. we have scheduled a virtual Zoom celebration that will I want to thank you for your belief in me, and for your begin at 6:30 PM on Wednesday October 28th. Thanks to the generous giving of individuals and support of the arts everywhere. You have given me organizations, as of July 31st of this year, we have more than money can buy – hope for a brighter day, received $214,614. This amount includes both donations and belief in the goodness of those acting in service. Newsletter in honor and memory of individuals, and to the Artists’ – Painter, Colorado Dear Members and Friends of the Fellowship, Fellowship general fund. We have given out $275,000 in What can be said about this past year that doesn’t cause deep sighs and aid to 112 artists. shaking heads? How about hearing the new catch phrases of the day? “Social In the past, our Annual Awards Dinner has been a great opportunity to renew friendships and catch up on the distancing.” “Shelter in place.” “No Mask, No Entry.” “Once in a century last year’s happenings. As for the future, I look forward to the dinners when we can gather together to honor pandemic.” those who give so much to the arts and to enjoy that warm camaraderie once more. Rather than succumb to the dark side, the Fellowship has joined other The Artists’ Fellowship is more involved in today’s relief and assistance to our artistic community than it ever philanthropic organizations stepping in to help in “these uncertain times.” has been. -

Sylvia Maier: About Sangomas and Soothsayers and Mischief

Sylvia Maier: About Sangomas and Soothsayers and Mischief 14 July - 12 September, 2020 515 West 29th St., New York Model Profile: Dion Mills Malin Gallery is pleased to present a solo exhibition of recent paintings by the Brooklyn- based artist Sylvia Maier: About Sangomas and Soothsayers and Mischief. A lifelong devotee of portraiture, Maier’s focuses her attention in the current exhibition on the Flatbush neighborhood of Brooklyn, where she has lived for three decades, and the adjacent Prospect Park area. The paintings in the exhibition modulate between fairly faithful depictions of the area and its denizens and a more fantastical framework with notes of magical realism. Maier typically employs an iterative process where she works both using live models and photographed images from the area. The models are typically intimates or friends, who spend hours sitting for the artist. For her more elaborate tableaux, Maier has her models, many of whom are artists or performers themselves, act out scenes she has constructed from photographic Dion Mills & Sylvia Maier - posing session for, The Beheading, 2020 images or imagined de novo. Maier’s close relationship with her models lend the portraits a startling degree of intimacy and psychological engagement. Two of the key works in About Sangomas and Soothsayers and Mischief, The Bicycle Thief (2020) and The Beheading (2020), features the image of Dion Mills - a photographer whom Maier considers to be “family.” Maier employs her portraiture as a means of discerning and appreciating the identity of her models on an intimate level - describing her goal as serving as a “witness to the personhood” of the model. -

Sherry Camhy

A Day in the Life of an Artist Sherry cAmhy By Wende Caporale* Not long ago, someone mentioned to me that they had prepared a “Bucket List” of experiences they desired to occur before they ostensibly “kick the bucket.” Many among us keep such lists with the hope that one-day they may be able to check off two or possibly three items. When I met recently with artist Sherry Camhy, she was waltzing from one item to the next on her Bucket List. Her work is represented in the permanent collections of the Israel Museum in Jerusalem, Israel; New Orleans Museum of Art, in New Orleans, Louisiana; and the New York Public Library in New York City, among others. Her art education includes the Art Students League of New York, National Academy of Art and Design, and New York Academy as well as pivotal private workshops. Camhy also holds a master’s degree from Columbia University, and most astonishingly, completed a gross anatomy, dissection course at New York University Medical School. What could possibly be a better way to learn anatomy of the human form? As a result, Camhy is well known for her figurative work particularly in black-and- white but she also enjoys working in many color mediums, oil painting, pastel, watercolor, pure pigment and mixed media in landscapes and still life compositions. A little-known fact is that she has won several awards for sculpture. Currently Camhy has been asked to curate a show at the National Arts Club in New York called The Silverpoint Exhibition, December 4 to 23, in which 40 artists from the United States and Canada will be represented. -

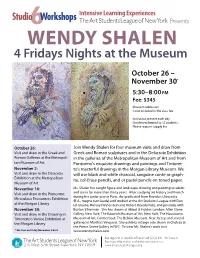

Class Description PDF Download

WENDY SHALEN 4 Fridays Nights at the Museum October 26 – November 30* 5:30–8:00 PM Fee: $345 Museum admission is not included in the class fee. Instructor present each day Enrollment limited to 12 students. Please request supply list October 26: Join Wendy Shalen for four museum visits and draw from Visit and draw in the Greek and Greek and Roman sculptures and in the Delacroix Exhibition Roman Galleries at the Metropoli- in the galleries of the Metropolitan Museum of Art and from tan Museum of Art Pontormo’s exquisite drawings and paintings and Tintoret- November 2: to’s masterful drawings in the Morgan Library Museum. We Visit and draw in the Delacroix will use black and white charcoal, sanguine conte or graph- Exhibition at the Metropolitan ite, col-Erase pencils, and or pastel pencils on toned paper. Museum of Art November 16: Ms. Shalen has taught figure and landscape drawing and painting to adults Visit and draw in the Pontormo: and teens for more than thirty years. After studying art history and French during her junior year in Paris, she graduated from Brandeis University Miraculous Encounters Exhibition (B.A., magna cum laude) and studied at the Art Students League with Dan- at the Morgan Library iel Greene, Harvey Dinnerstein and Robert Beverly Hale, and privately with November 30: Burton Silverman. She has shown at Abbot & Holder, London; Allan Stone Visit and draw in the Drawing in Gallery, New York; The Katonah Museum of Art, New York; The Housatonic Tintoretto’s Venice Exhibition at Museum of Art, Connecticut; The Belskie Museum, New Jersey; and several the Morgan Library galleries in Martha’s Vineyard.