Do the Right Thing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PD GLADIATORS FITNESS NETWORK - SAMPLE SCHEDULE Now Operated by the Parkinson's Foundation

PD GLADIATORS FITNESS NETWORK - SAMPLE SCHEDULE Now Operated by the Parkinson's Foundation Classes Instructor Location Facility MONDAY 10:45am - 11:45am Parkinson's Movement Class YMCA Staff East Lake East Lake Family YMCA 11:00 am - 12:00 pm Parkinson's Movement Class YMCA Staff Newnan Summit Family YMCA 11:00 am - 12:15 pm Optimizing Exercise (1st and 3rd M) LDBF Sandy Springs Fitness Firm 11:00 am - 12:15 pm Boxing Training for PD (I/II) LDBF Sandy Springs Fitness Firm 11:15 am - 12:10 pm Parkinson's Movement Class YMCA Staff Canton G. Cecil Pruett Comm. Center Family YMCA 11:30 am - 12:25 pm Parkinson's Movement Class YMCA Staff Chamblee Cowart Family/Ashford Dunwoody YMCA 11:35 am - 12:25 pm Parkinson's Movement Class YMCA Staff Lawrenceville J.M. Tull-Gwinnett Family YMCA 12:00pm - 12:45pm Parkinson's Movement Class YMCA Staff Cumming Forsyth County Family YMCA 12:30 pm - 1:30pm Boxing Training for PD (III/IV) LDBF Sandy Springs Fitness Firm 1:00 pm - 1:30 pm PD Group Cycling YMCA Staff Cumming Forsyth County Family YMCA 1:20pm - 2:15pm PD Group Cycling YMCA Staff Alpharetta Ed Isakson/Alpharetta Family YMCA 2:30 pm - 3:30 pm Knock Out PD - Boxing TITLE Boxing Staff Kennesaw TITLE Boxing Club Kennesaw 7:00 pm - 8:00 pm Dance for Parkinson's Paulo Manso de Sousa Newnan Southern Arc Dance TUESDAY 10:30 am - 11:15 am Dance for Parkinson's Paulo Manso de Sousa Newnan Southern Arc Dance 10:30 am - 11:30 am Ageless Grace Lori Trachtenberg Vinings Kaiser Permanente (members only) 10:30 am - 11:15 am Parkinson's Movement Class YMCA Staff Covington Covington Family YMCA 11:00 am - 12:00 pm Parkinson's Movement Class YMCA Staff Decatur South DeKalb Family YMCA 11:00 am - 12:15 pm Boxing Training for PD (I/II) LDBF Sandy Springs Fitness Firm 11:30 am - 12:00 pm PD Group Cycling YMCA Staff Kennesaw Northwest Family YMCA 12:00 pm - 1:00 pm Dance for Parkinson's Eleanor/Rob Rogers Cumming Still Pointe Dance Studios 12:15 pm - 12:45 pm Parkinson's Movement Class YMCA Staff Buckhead Carl E. -

Finska Spelare I HV71

MEDIAGUIDE SÄSONGEN 2016/2017 HV71 MEDIAGUIDE 2016/2017 HV71 MEDIAGUIDE 2016/2017 SM-SLUTSPE INNEHÅLL 3 39 Kontaktpersoner Tränare 1971-2016 4 40 Truppen 16/17 Individuella klubbrekord 13 46 Lagledning 16/17 Tröjnummer 14 51 Nyförvärv och förluster 16/17 Tröjor i taket 16 62 Historia om HV71 Finska spelare i HV71 17 63 Historia om dom gamla klubbarna Utmärkelser/troféer 20 64 Poängligor 1979-2016 Lokala utmärkelser 27 65 Tabeller 1971-2016 Hockey Hall of fame 34 66 Flest spelade matcher HV-spelare i NHL-draften 37 69 Flest spelade slutspelsmatcher HV-spelare i de stora turneringarna MEDIAGUIDE SÄSONGEN 2016/2017 2 HV71 MEDIAGUIDE 2016/2017 SM-SLUTSPE KONTAKTPERSONER ORDFÖRANDE Sten-Åke Karlsson, [email protected], 070-698 42 15 KLUBBDIREKTÖR Agne Bengtsson, [email protected], 036-299 71 18 GENERAL MANAGER SPORT Peter Ekelund, [email protected], 036-299 71 11 SPORTCHEF Johan Hult, [email protected], 036-299 71 14 ASS. SPORTCHEF Johan Davidsson, [email protected], 036-299 71 29 MARKNADSCHEF Johan Skogeryd, [email protected], 036-299 71 04 PRESSANSVARIG/ACKREDITERING Johan Freijd, [email protected], 036-299 71 15 BILJETTER Robert Linge, [email protected], 036-299 71 00 ARENACHEF Bengt Halvardsson, [email protected], 0733-27 67 99 HV71, Kinnarps Arena, 554 54 JÖNKÖPING www.hv71.se | [email protected] twitter.com/hv71 | facebook.com/hv71 | instagram.com/hv71 | youtube.com/hv71 MEDIAGUIDE SÄSONGEN 2016/2017 3 HV71 MEDIAGUIDE 2016/2017 HV71 MEDIAGUIDE 2016/2017 SM-SLUTSPE TRUPPEN 16/17 MÅLVAKTER 30 LINUS SÖDERSTRÖM FÖDD 1996-08-23 A-SÄSONGER I HV71 NY FÖDELSEORT STOCKHOLM SHL-MATCHER I HV71 - LÄNGD 195 CM SLUTSPELSMA. -

Media Kit San Jose Barracuda Vs Ontario Reign Game #G-4: Friday, April 29, 2016

Media Kit San Jose Barracuda vs Ontario Reign Game #G-4: Friday, April 29, 2016 theahl.com San Jose Barracuda (1-2-0-0) vs. Ontario Reign (2-1-0-0) Apr 29, 2016 -- Citizens Business Bank Arena AHL Game #G-4 GOALIES GOALIES # Name Ht Wt GP W L SO GAA SV% # Name Ht Wt GP W L SO GAA SV% 1 Troy Grosenick 6-1 185 1 0 0 0 0.00 1.000 29 Michael Houser 6-2 190 0 0 0 0 0.00 0.000 30 Aaron Dell 6-0 205 3 1 2 0 2.44 0.938 31 Peter Budaj 6-1 192 3 2 1 0 1.69 0.918 SKATERS 35 Jack Flinn 6-8 233 0 0 0 0 0.00 0.000 # Name Pos Ht Wt GP G A Pts. PIM +/- SKATERS 3 Karl Stollery D 6-0 180 3 0 0 0 0 -2 # Name Pos Ht Wt GP G A Pts. PIM +/- 11 Bryan Lerg LW 5-10 175 3 1 0 1 0 -1 2 Chaz Reddekopp D 6-3 220 0 0 0 0 0 0 13 Raffi Torres LW 6-0 220 0 0 0 0 0 0 3 Derek Forbort D 6-4 218 3 0 1 1 0 0 17 John McCarthy LW 6-1 195 3 0 0 0 0 -2 4 Kevin Gravel D 6-4 200 2 0 1 1 0 1 21 Jeremy Morin LW 6-1 196 3 0 0 0 2 1 5 Vincent LoVerde D 5-11 205 3 0 0 0 2 0 23 Frazer McLaren LW 6-5 230 1 0 0 0 2 0 7 Brett Sutter C 6-0 192 3 0 1 1 2 -1 40 Ryan Carpenter RW 6-0 195 3 1 0 1 0 2 8 Zach Leslie D 6-0 175 0 0 0 0 0 0 41 Mirco Mueller D 6-3 210 3 0 0 0 4 1 9 Adrian Kempe LW 6-1 187 3 2 0 2 2 4 47 Joakim Ryan D 5-11 185 3 0 3 3 0 -1 10 Mike Amadio C 6-1 196 1 0 0 0 0 0 49 Gabryel Boudreau LW 5-11 180 2 0 0 0 0 -2 11 Kris Newbury C 5-11 213 3 0 1 1 2 -1 51 Patrick McNally D 6-2 205 2 0 0 0 0 0 12 Jonny Brodzinski RW 6-0 202 3 2 1 3 2 3 53 Nikita Jevpalovs RW 6-1 210 3 1 0 1 0 -2 15 Paul Bissonnette LW 6-2 216 3 0 1 1 2 0 55 Petter Emanuelsson RW 6-1 200 0 0 0 0 0 0 16 Sean Backman -

Gladiators Handout

Gladiators Handout Who were gladiators? Mostly unfree individuals such as condemned criminals, prisoners or war, slaves. Some were volunteers (freedmen or low class free-born men) who did it for fame and money. Women could be gladiators – called Gladeatrix – but these were rare. Different types of gladiatorial games • Animals in the arena - Venationes • Executions • Man vs man Q. What is the name of the arena (above) recreated for the film Gladiator (2000)? Q. How many people could it hold and when was it built? Types of gladiators Gladiators were distinguished by the kind of armour they wore, the weapons they used and their style of fighting. • Eques These would begin on horseback and usually finish fighting in hand-to-hand combat. • Hoplomachus These were heavy-weapons fighters who fought with a long spear and dagger. • Provocator These were attackers who were usually heavily armed. Generally, they were slower and less agile than the other fighters listed above. They wore pectoral covering the vulnerable upper chest, padded arm protector and one greave on his left leg. • Retiarius These were known as “net-men”, i.e. they fought with a net with a long trident and small dagger. They were the quickest and most mobile of all the fighters. They fought with practically no armour that made them more vulnerable to serious injuries during fights. • Bestiarius These were individuals who were trained to fight against wild animals such as tigers and lions. Mostly criminals were sentenced to fight in this role, they, however, would not be trained nor armed. They were the least popular of all the gladiator fighters. -

PRESS RELEASE MOTUL FIM Ice Speedway Gladiators World

PRESS RELEASE MIES, 23/01/2015 FOR MORE INFORMATION: ISABELLE LARIVIÈRE COMMUNICATION MANAGER [email protected] TEL +41 22 950 95 68 MOTUL FIM Ice Speedway Gladiators World Championship 2015 Starting List – Final Series, updated 23, January (Changes in bold) N° RIDER FMN COUNTRY 1 Daniil Ivanov MFR Russia 2 Dimitry Koltakov MFR Russia 3 Dimitry Khomitsevich MFR Russia 4 Igor Kononov MFR Russia Stefan Svensson 5 SVEMO Sweden 6 Jan Klatovsky ACCR Czech Republic 7 Günther Bauer DMSB Germany 8 Stefan Pletschacher DMSB Germany 9 Per-Anders Lindström SVEMO Sweden 10 Franz Zorn OeAMTC Austria 11 Vitaly Khomitsevich MFR Russia 12 Hans Weber DMSB Germany 13 Mats Järf SML Finland 14 Antonin Klatovsky ACCR Czech Republic 15 Harald Simon OeAMTC Austria 16 FMNR Wild Card To be accepted by CCP Reserve 1 Reserve 2 11 ROUTE DE SUISSE TEL +41 22 950 95 00 CH – 1295 MIES FAX +41 22 950 95 01 [email protected] FOUNDED 1904 WWW.FIM-LIVE.COM Nominated Substitute Riders List N° RIDER FMN COUNTRY 19 Daniel Henderson SVEMO Sweden 20 Niclas Kallin Svensson SVEMO Sweden 21 Jimmy Olsen SVEMO Sweden 22 Ove Ledstrom SVEMO Sweden 23 Max Niedermaier DMSB Germany -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- About the FIM (www.fim-live.com) The FIM (Fédération Internationale de Motocyclisme) founded in 1904, is the governing body for motorcycle sport and the global advocate for motorcycling. The FIM is an independent association formed by 112 National Federations throughout the world. It is recognised as the sole competent authority in motorcycle sport by the International Olympic Committee (IOC). Among its 50 FIM World Championships the main events are MotoGP, Superbike, Endurance, Motocross, Supercross, Trial, Enduro, Cross-Country Rallies and Speedway. -

Original Llp

EX PARTE OR LATE FILED HOGAN &HAKrsoN ORIGINAL LLP. DOCKET FILE COpy ORIGINAL COLUWBIA SQUARE 5511 THIRTEENTH STREET, NW MACE J. IOIINSTIIN WASHINGTON, DC 20004-1109 'AUNI.. DlDer DIAL (202) 631-M77 TIL (102) 657-6800 October 27, 1995 RECE/~D) 637·5910 OCl271995 BYHAND DELIVERY fal£RAL =~~i~~~:-S8ION The Secretary Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. 20554 Re: Notice ofEx Parte Presentation in MM Docket No. 93-48, Policies and Rules Concerning Children's Television Programming Dear Sir: Notice is hereby given that on October 26, 1995, representatives ofFox Broadcasting Company ("FBC") and its subsidiary, the Fox Children's Network ("FCN"), and the Fox Affiliates Association met with Commissioners James H. Quello and Rachelle B. Chong, Chiefof StaffBlair Levin, Counsel to the Chairman Julius Genachowski, and Legal Advisors Jane Mago, David R. Siddall and Lisa B. Smith in connection with the above-referenced proceeding. The meetings were attended by the following: Preston R. Padden, President, Network Distribution Fox Broadcasting Company Peggy K. Binzel, Senior Vice President - Government Relations The News Corporation Limited Margaret Loesch, President Fox Children's Network Patrick Mullen, Vice-Chairman Fox Affiliates Association Stuart Powell, Chairman, FCN Oversight Committee Fox Affiliates Association No. of Copiee rec'd CJd-/ ListABCDE --. LOItDON ...... I'IIAGW WMMW UL'l'DIOa,Ie .-rHaIM,lID OOLOIIADO U'IIINOI, 00 ......00 1iICUAN. VA •AJ/IIiI1IM CJIiDI HOGAN &HAlrrsoN L.L.P. The Secretary October 27, 1995 Page 2 The purpose ofthe meetings was to present and discuss (1) the results ofa survey ofthe types and amount of children's educational and informational programming broadcast by FCN and its affiliates, and (2) a videotape featuring examples ofthe children's educational and informational programming produced by FCN. -

2021 Nhl Awards Presented by Bridgestone Information Guide

2021 NHL AWARDS PRESENTED BY BRIDGESTONE INFORMATION GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS 2021 NHL Award Winners and Finalists ................................................................................................................................. 3 Regular-Season Awards Art Ross Trophy ......................................................................................................................................................... 4 Bill Masterton Memorial Trophy ................................................................................................................................. 6 Calder Memorial Trophy ............................................................................................................................................. 8 Frank J. Selke Trophy .............................................................................................................................................. 14 Hart Memorial Trophy .............................................................................................................................................. 18 Jack Adams Award .................................................................................................................................................. 24 James Norris Memorial Trophy ................................................................................................................................ 28 Jim Gregory General Manager of the Year Award ................................................................................................. -

Olympic Ice Hockey Media Guide T Orino 2006

Olympic Ice Hockey Media Guide 2006 Torino International Ice Hockey Federation The XX Olympic Winter Games Torino 2006 Players named to 4th Olympics Czech Republic: Dominik Hasek, G, 1988, 1998, 2002 Robert Lang, F, 1992, 1998, 2002 Finland: Teppo Numminen, D, 1988, 1998, 2002 Photo: Al Behrman, Associated Press Teemu Selanne, F, 1992, 1998, 2002 Sami Kapanen, F, 1994, 1998, 2002 Jere Lehtinen, F, 1994, 1998, 2002 Germany: U.S. defenseman Chris Chelios Jan Benda, D/F, 1994, 1998, 2002 Stefan Ustorf, F, 1994, 1998, 2002 Italy: Lucio Topatigh, F, 1992, 1994, 1998 Russia: Darius Kasparaitis, D, 1992, 1998, 2002 Alexei Zhamnov, F,1992, 1998, 2002* Sweden: Jorgen Jonsson, F, 1994, 1998, 2002 USA: Stamp: Swedish Post, Chris Chelios, D, 1984, 1998, 2002 Photo: Gary Hershorn, Reuters Keith Tkachuk, F, 1992, 1998, 2002 *named to initial roster, but injured Did you know? Did you know? Fourteen players who were named to their Olympic rosters on December 22 will, The only time an Olympic gold medal was decided in a game winning shot barring injuries, participate in their fourth Olympic ice hockey tournament. competition (“shootout”) was in 1994 in Lillehammer. A brave Team Canada, This group of international hockey veterans is lead by 44-year old U.S. defenseman comprised mostly of minor leaguers and amateurs, held a 2 – 1 lead until 18.11 Chris Chelios who will also set another Olympic record, becoming the first to of the third period when Sweden scored a power-play goal to even it up. play in an Olympic hockey tournament 22 years after taking part in his first, Canada also had a 2-0 lead in the shootout competition, but with the score 1984 in Sarajevo. -

2003 SC Playoff Summaries

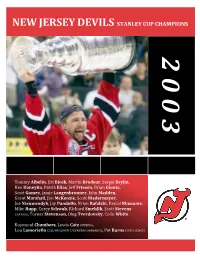

rAYM NEW JERSEY DEVILS STANLEY CUP CHAMPIONS 2 0 0 3 Tommy Albelin, Jiri Bicek, Martin Brodeur, Sergei Brylin, Ken Daneyko, Patrik Elias, Jeff Friesen, Brian Gionta, Scott Gomez, Jamie Langenbrunner, John Madden, Grant Marshall, Jim McKenzie, Scott Niedermayer, Joe Nieuwendyk, Jay Pandolfo, Brian Rafalski, Pascal Rheaume, Mike Rupp, Corey Schwab, Richard Smehlik, Scott Stevens CAPTAIN, Turner Stevenson, Oleg Tverdovsky, Colin White Raymond Chambers, Lewis Catz OWNERS, Lou Lamoriello CEO/PRESIDENT/GENERAL MANAGER, Pat Burns HEAD COACH © Steve Lansky 2010 bigmouthsports.com NHL and the word mark and image of the Stanley Cup are registered trademarks and the NHL Shield and NHL Conference logos are trademarks of the National Hockey League. All NHL logos and marks and NHL team logos and marks as well as all other proprietary materials depicted herein are the property of the NHL and the respective NHL teams and may not be reproduced without the prior written consent of NHL Enterprises, L.P. Copyright © 2010 National Hockey League. All Rights Reserved. 0 2003 EASTERN CONFERENCE QUARTER-FINAL 1 OTTAWA SENATORS 113 v. 8 NEW YORK ISLANDERS 83 GM JOHN MUCKLER, HC JACQUES MARTIN v. GM MIKE MILBURY, HC PETER LAVIOLETTE SENATORS WIN SERIES IN 5 Wednesday, April 9 Saturday, April 12 ISLANDERS 3 @ SENATORS 0 ISLANDERS 0 @ SENATORS 3 FIRST PERIOD FIRST PERIOD 1. NEW YORK, Dave Scatchard 1 (Roman Hamrlik, Janne Niinimaa) 7:59 GWG 1. OTTAWA, Marian Hossa 1 (Bryan Smolinski, Zdeno Chara) 6:43 GWG 2. NEW YORK, Alexei Yashin 1 (Randy Robitaille, Roman Hamrlik) 11:35 2. OTTAWA, Vaclav Varada 1 (Martin Havlat) 8:24 Penalties – S Webb NY (tripping) 6:12, W Redden O (interference) 7:22, M Parrish NY (roughing) 9:24, Penalties – S Webb NY (charging) 5:15, M Fisher O (obstr interference) 5:50, D Scatchard NY (interference) 18:31 P Schaefer O (roughing) 9:24, K Rachunek O (roughing) 9:24, C Phillips O (obstr interference) 17:07 SECOND PERIOD SECOND PERIOD 3. -

Saturday Morning, Oct. 31

SATURDAY MORNING, OCT. 31 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 VER COM Good Morning America (N) (cc) KATU News This Morning - Sat (cc) 41035 Emperor New The Replace- That’s So Raven That’s So Raven Hannah Montana Zack & Cody 2/KATU 2 2 54847 68615 ments 99073 36615 64899 (TVG) 7219 8948 5:00 The Early Show (N) (cc) Busytown Mys- Noonbory-7 Fusion 96412 Garden Time Busytown Myster- Noonbory-7 Paid 54035 Paid 82219 Paid 31509 Paid 32238 6/KOIN 6 6 (Cont’d) 939054 teries (N) 67829 82306 95783 ies (N) 86035 17493 Newschannel 8 at Sunrise at 6:00 Newschannel 8 at 7:00 (N) (cc) 87851 Willa’s Wild Life Babar (cc) Shelldon (cc) Jane & the Paid 26677 Paid 27306 8/KGW 8 8 AM (N) (cc) 24493 (N) (cc) 70801 (TVY7) 34031 (TVY7) 72431 Dragon 70865 A Place of Our Donna’s Day Mama-Movies Angelina Balle- Animalia (TVY) WordGirl (TVY7) The Electric Com- Fetch! With Ruff Victory Garden P. Allen Smith’s Sewing With Martha’s Sewing 10/KOPB 10 10 Own 22798 14431 47257 rina: Next 26764 46054 45325 pany 36677 Ruffman 67035 (N) (TVG) 85293 Garden 25561 Nancy 82257 Room 83986 Good Day Oregon Saturday (N) 872580 Paid 30493 Paid 54073 Dog Tales (cc) Animal Rescue Into the Wild Gladiators 2000 Saved by the Bell 12/KPTV 12 12 (TVG) 85431 (TVG) 90851 50257 77325 78054 Portland Public Affairs 80615 Paid 46783 Paid 25290 Paid 46696 Paid 45967 Paid 36219 Paid 74967 Paid 54702 Paid 66851 Paid 67580 22/KPXG 5 5 Sing Along With Dooley & Pals Dr. -

Hiking Dix Mountain

FREE! COVERING SEPTEMBER UPSTATE NY 2016 SINCE 2000 Hiking Dix Mountain CONTENTS A Scenic Trail with 1 Hiking & Backpacking Dix Mountain Expansive Lookouts 3 Running & Walking By Bill Ingersoll Leaves, Pumpkins & ▲ HIKERS REACHING THE DIX his trail is arguably the most scenic approach to Dix By all means, make the short SUMMIT ARE REWARDED WITH Fall Classics THIS PERFECT VIEW OF GOTHICS. Mountain, the sixth highest peak in the High Peaks. Although side trip if you have the time. BILL INGERSOLL 5 News Briefs T it is nearly seven miles long, there are several attractive If you are planning to linger, landmarks to enjoy along the way: Round Pond, the North Fork 5 From the Publisher & Editor note that Round Pond has been stocked with brook trout. Boquet and its lean-to, and the brief traverse of Dix’s northern The main trail bears right at the junction and circles through 6-9 CALENDAR OF EVENTS slide. Although Bob Marshall and other hikers in the 1920s found the birch forest to Round’s northern shore. Of all the Round September to cause for complaint in the condition of the trail after the twin fires Ponds in the Adirondack Park, this is one of the few in which November Events of 1903 and 1913, many of those sins have been erased by the pas- the name is almost geometrically appropriate. The trail passes sage of time. The one fault that remains is the steepness that exists close around the shore, with numerous opportunities to enjoy 11 Bicycling on the uppermost portion of the trail, above the slide. -

The BG News October 18, 1996

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU BG News (Student Newspaper) University Publications 10-18-1996 The BG News October 18, 1996 Bowling Green State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news Recommended Citation Bowling Green State University, "The BG News October 18, 1996" (1996). BG News (Student Newspaper). 6068. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news/6068 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in BG News (Student Newspaper) by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. Opinion H E Tom Mather gets a busy signal. Page 2 Nation Browns Backers coming to Proposition 209 decided by Saturday's football game against ballot. Ball State. Page 7 Page 3 NEWS Friday, October 18, 1996 Bowling Green, Ohio Volume 83, Issue 180 The News' Liquor Screw Jump Briefs Aspen chamber en- agents semble opening for Forefront Series Aspen Music Festival's arrest chamber ensemble, SOUNDINGS, will present the opening concert on the Music at the Forefront Se- ries on Oct. 25 at the Uni- in city versity. The free perform- ance is scheduled for 8 p.m. in Bryan Recital Hall of the Brandon Wray Moore Musical Arts Center. The BC News The appearance is spon- sored by the College of Mu- If you were sitting in one of sical Arts' MidAmerican Bowling Green's numerous bar Center for Contemporary and grills this weekend drinking Music.