Installing a USB External Hard Drive Backup (Linux)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Practice Test Version 1.8 LPI 117-101: Practice Exam QUESTION NO: 1 CORRECT TEXT

LPI 117-101 117-101 LPI 101 General Linux, Part I Practice Test Version 1.8 LPI 117-101: Practice Exam QUESTION NO: 1 CORRECT TEXT You suspect that a new ethernet card might be conflicting with another device. Which file should you check within the /proc tree to learn which IRQs are being used by which kernel drives? Answer: interrupts QUESTION NO: 2 How many SCSI ids for peripherals can SCSI-1 support? A. 5 B. 6 C. 7 D. 8 Answer: C Explanation: SCSI-1 support total 7 peripherals. There are several different types of SCSI devices. The original SCSI specification is commonly referred to as SCSI-1. The newer specification, SCSI-2, offers increased speed and performance, as well as new commands. Fast SCSI increases throughput to more than 10MB per second. Fast-Wide SCSI provides a wider data path and throughput of up to 40MB per second and up to 15 devices. There there are Ultra-SCSI and Ultra-Wide-SCSI QUESTION NO: 3 You need to install a fax server. Which type of fax/modem should you install to insure Linux compatibility? Test-King.com A. External Serial Fax/modem B. External USB Fax/modem C. Internal ISA Fax/modem D. Internal PCI Fax/modem Answer: A QUESTION NO: 4 You are running Linux 2.0.36 and you need to add a USB mouse to your system. Which of the following statements is true? "Welcome to Certification's Main Event" - www.test-king.com 2 LPI 117-101: Practice Exam A. You need to rebuild the kernel. -

Control of Protein Orientation on Gold Nanoparticles † ∥ † § † ∥ ⊥ Wayne Lin, Thomas Insley, Marcus D

Article pubs.acs.org/JPCC Control of Protein Orientation on Gold Nanoparticles † ∥ † § † ∥ ⊥ Wayne Lin, Thomas Insley, Marcus D. Tuttle, Lingyang Zhu, Deborah A. Berthold, Petr Kral,́, † ‡ # † Chad M. Rienstra,*, , , and Catherine J. Murphy*, † ‡ Department of Chemistry and Department of Biochemistry, University of Illinois at Urbana−Champaign, 600 South Matthews Avenue, Urbana, Illinois 61801, United States § School of Chemical Sciences, University of Illinois at Urbana−Champaign, 505 South Matthews Avenue, Urbana, Illinois 61801, United States ∥ ⊥ Department of Chemistry and Department of Physics, University of Illinois at Chicago, 845 West Taylor Street, Chicago, Illinois 60607, United States # Center for Biophysics and Computational Biology, University of Illinois at Urbana−Champaign, 607 South Matthews Avenue, Urbana, Illinois 61801, United States *S Supporting Information ABSTRACT: Gold nanoparticles (Au NPs) have attracted much attention due to their potential applications in nanomedicine. While numerous studies have quantified biomolecular adsorption to Au NPs in terms of equilibrium binding constants, far less is known about biomolecular orientation on nanoparticle surfaces. In this study, the binding of the protein α-synuclein to citrate and (16- mercaptohexadecyl)trimethylammonium bromide (MTAB)-coated 12 nm Au NPs is examined by heteronuclear single quantum coherence NMR spectroscopy to provide site-specific measurements of protein−nanoparticle binding. Molecular dynamics simulations support the orientation assignments, which -

File System, Files, and *Tab /Etc/Fstab

File system, files, and *tab File system files directories volumes, file systems mounting points local versus networked file systems 1 /etc/fstab Specifies what is to be mounted where and how fs_spec: describes block special device for remote filesystem to be mounted fs_file: describes the mount point fs_vfstype: describes the type of file system fs_mntops: describes the mount options associated with the filesystem 2 /etc/fstab cont. fs_freq: used by the dump command fs_passno: used by fsck to determine the order in which checks are done at boot time. Root file systems should be specified as 1, others should be 2. Value 0 means that file system does not need to be checked 3 /etc/fstab 4 from blocks to mounting points metadata inodes directories superblocks 5 mounting file systems mounting e.g., mount -a unmounting manually or during shutdown umount 6 /etc/mtab see what is mounted 7 Network File System Access file system (FS) over a network looks like a local file system to user e.g. mount user FS rather than duplicating it (which would be a disaster) Developed by Sun Microsystems (mid 80s) history for NFS: NFS, NFSv2, NFSv3, NFSv4 RFC 3530 (from 2003) take a look to see what these RFCs are like!) 8 Network File System How does this actually work? server needs to export the system client needs to mount the system server: /etc/exports file client: /etc/fstab file 9 Network File System Security concerns UID GID What problems could arise? 10 Network File System example from our raid system (what is a RAID again?) Example of exports file from -

Filesystem Hierarchy Standard

Filesystem Hierarchy Standard LSB Workgroup, The Linux Foundation Filesystem Hierarchy Standard LSB Workgroup, The Linux Foundation Version 3.0 Publication date March 19, 2015 Copyright © 2015 The Linux Foundation Copyright © 1994-2004 Daniel Quinlan Copyright © 2001-2004 Paul 'Rusty' Russell Copyright © 2003-2004 Christopher Yeoh Abstract This standard consists of a set of requirements and guidelines for file and directory placement under UNIX-like operating systems. The guidelines are intended to support interoperability of applications, system administration tools, development tools, and scripts as well as greater uniformity of documentation for these systems. All trademarks and copyrights are owned by their owners, unless specifically noted otherwise. Use of a term in this document should not be regarded as affecting the validity of any trademark or service mark. Permission is granted to make and distribute verbatim copies of this standard provided the copyright and this permission notice are preserved on all copies. Permission is granted to copy and distribute modified versions of this standard under the conditions for verbatim copying, provided also that the title page is labeled as modified including a reference to the original standard, provided that information on retrieving the original standard is included, and provided that the entire resulting derived work is distributed under the terms of a permission notice identical to this one. Permission is granted to copy and distribute translations of this standard into another language, under the above conditions for modified versions, except that this permission notice may be stated in a translation approved by the copyright holder. Dedication This release is dedicated to the memory of Christopher Yeoh, a long-time friend and colleague, and one of the original editors of the FHS. -

Advanced Bash-Scripting Guide

Advanced Bash−Scripting Guide An in−depth exploration of the art of shell scripting Mendel Cooper <[email protected]> 2.2 31 October 2003 Revision History Revision 0.1 14 June 2000 Revised by: mc Initial release. Revision 0.2 30 October 2000 Revised by: mc Bugs fixed, plus much additional material and more example scripts. Revision 0.3 12 February 2001 Revised by: mc Another major update. Revision 0.4 08 July 2001 Revised by: mc More bugfixes, much more material, more scripts − a complete revision and expansion of the book. Revision 0.5 03 September 2001 Revised by: mc Major update. Bugfixes, material added, chapters and sections reorganized. Revision 1.0 14 October 2001 Revised by: mc Bugfixes, reorganization, material added. Stable release. Revision 1.1 06 January 2002 Revised by: mc Bugfixes, material and scripts added. Revision 1.2 31 March 2002 Revised by: mc Bugfixes, material and scripts added. Revision 1.3 02 June 2002 Revised by: mc 'TANGERINE' release: A few bugfixes, much more material and scripts added. Revision 1.4 16 June 2002 Revised by: mc 'MANGO' release: Quite a number of typos fixed, more material and scripts added. Revision 1.5 13 July 2002 Revised by: mc 'PAPAYA' release: A few bugfixes, much more material and scripts added. Revision 1.6 29 September 2002 Revised by: mc 'POMEGRANATE' release: some bugfixes, more material, one more script added. Revision 1.7 05 January 2003 Revised by: mc 'COCONUT' release: a couple of bugfixes, more material, one more script. Revision 1.8 10 May 2003 Revised by: mc 'BREADFRUIT' release: a number of bugfixes, more scripts and material. -

Oracle® Linux 7 Managing File Systems

Oracle® Linux 7 Managing File Systems F32760-07 August 2021 Oracle Legal Notices Copyright © 2020, 2021, Oracle and/or its affiliates. This software and related documentation are provided under a license agreement containing restrictions on use and disclosure and are protected by intellectual property laws. Except as expressly permitted in your license agreement or allowed by law, you may not use, copy, reproduce, translate, broadcast, modify, license, transmit, distribute, exhibit, perform, publish, or display any part, in any form, or by any means. Reverse engineering, disassembly, or decompilation of this software, unless required by law for interoperability, is prohibited. The information contained herein is subject to change without notice and is not warranted to be error-free. If you find any errors, please report them to us in writing. If this is software or related documentation that is delivered to the U.S. Government or anyone licensing it on behalf of the U.S. Government, then the following notice is applicable: U.S. GOVERNMENT END USERS: Oracle programs (including any operating system, integrated software, any programs embedded, installed or activated on delivered hardware, and modifications of such programs) and Oracle computer documentation or other Oracle data delivered to or accessed by U.S. Government end users are "commercial computer software" or "commercial computer software documentation" pursuant to the applicable Federal Acquisition Regulation and agency-specific supplemental regulations. As such, the use, reproduction, duplication, release, display, disclosure, modification, preparation of derivative works, and/or adaptation of i) Oracle programs (including any operating system, integrated software, any programs embedded, installed or activated on delivered hardware, and modifications of such programs), ii) Oracle computer documentation and/or iii) other Oracle data, is subject to the rights and limitations specified in the license contained in the applicable contract. -

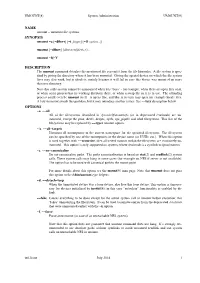

Name Synopsis Description Options

UMOUNT(8) System Administration UMOUNT(8) NAME umount − unmount file systems SYNOPSIS umount −a [−dflnrv][−t fstype][−O option...] umount [−dflnrv]{directory|device}... umount −h|−V DESCRIPTION The umount command detaches the mentioned file system(s) from the file hierarchy. A file system is spec- ified by giving the directory where it has been mounted. Giving the special device on which the file system livesmay also work, but is obsolete, mainly because it will fail in case this device was mounted on more than one directory. Note that a file system cannot be unmounted when it is ’busy’ - for example, when there are open files on it, or when some process has its working directory there, or when a swap file on it is in use. The offending process could evenbe umount itself - it opens libc, and libc in its turn may open for example locale files. Alazy unmount avoids this problem, but it may introduce another issues. See −−lazy description below. OPTIONS −a, −−all All of the filesystems described in /proc/self/mountinfo (or in deprecated /etc/mtab) are un- mounted, except the proc, devfs, devpts, sysfs, rpc_pipefs and nfsd filesystems. This list of the filesystems may be replaced by −−types umount option. −A, −−all−targets Unmount all mountpoints in the current namespace for the specified filesystem. The filesystem can be specified by one of the mountpoints or the device name (or UUID, etc.). When this option is used together with −−recursive,then all nested mounts within the filesystem are recursively un- mounted. This option is only supported on systems where /etc/mtab is a symlink to /proc/mounts. -

Managing Network File Systems in Oracle® Solaris 11.4

Managing Network File Systems in ® Oracle Solaris 11.4 Part No: E61004 August 2021 Managing Network File Systems in Oracle Solaris 11.4 Part No: E61004 Copyright © 2002, 2021, Oracle and/or its affiliates. This software and related documentation are provided under a license agreement containing restrictions on use and disclosure and are protected by intellectual property laws. Except as expressly permitted in your license agreement or allowed by law, you may not use, copy, reproduce, translate, broadcast, modify, license, transmit, distribute, exhibit, perform, publish, or display any part, in any form, or by any means. Reverse engineering, disassembly, or decompilation of this software, unless required by law for interoperability, is prohibited. The information contained herein is subject to change without notice and is not warranted to be error-free. If you find any errors, please report them to us in writing. If this is software or related documentation that is delivered to the U.S. Government or anyone licensing it on behalf of the U.S. Government, then the following notice is applicable: U.S. GOVERNMENT END USERS: Oracle programs (including any operating system, integrated software, any programs embedded, installed or activated on delivered hardware, and modifications of such programs) and Oracle computer documentation or other Oracle data delivered to or accessed by U.S. Government end users are "commercial computer software" or "commercial computer software documentation" pursuant to the applicable Federal Acquisition Regulation and agency-specific supplemental regulations. As such, the use, reproduction, duplication, release, display, disclosure, modification, preparation of derivative works, and/or adaptation of i) Oracle programs (including any operating system, integrated software, any programs embedded, installed or activated on delivered hardware, and modifications of such programs), ii) Oracle computer documentation and/or iii) other Oracle data, is subject to the rights and limitations specified in the license contained in the applicable contract. -

On-Demand Host-Container Filesystem Sharing

TECHNION – ISRAEL INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY On-Demand Host-Container Filesystem Sharing Bassam Yassin and Guy Barshatski Supervisor: Noam Shalev NSSL Labs Winter 2016 Implementing and adding a new feature to Docker open source project which allows a host to add extra volume to a running container 1 Contents List Of Figures ............................................................................................................................ 3 1 Abstract ................................................................................................................................. 4 2 Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 5 3 Background Theory ................................................................................................................ 6 3.1 Device .............................................................................................................................. 6 3.1.1 Character devices ..................................................................................................... 6 3.1.2 Block devices ............................................................................................................ 6 3.2 Unix-Like Filesystem ....................................................................................................... 7 3.3 Namespaces and Cgroups ............................................................................................... 9 3.3.1 Namespaces ............................................................................................................. -

Effects of Surfactants and Polyelectrolytes on the Interaction

Article pubs.acs.org/Langmuir Effects of Surfactants and Polyelectrolytes on the Interaction between a Negatively Charged Surface and a Hydrophobic Polymer Surface † † ‡ § ∥ Michael V. Rapp, Stephen H. Donaldson, Jr., Matthew A. Gebbie, Yonas Gizaw, Peter Koenig, § † ‡ Yuri Roiter, and Jacob N. Israelachvili*, , † Department of Chemical Engineering, University of California, Santa Barbara, California 93106-5080, United States ‡ Materials Department, University of California, Santa Barbara, California 93106-5050, United States § Winton Hill Business Center, The Procter & Gamble Company, 6210 Center Hill Avenue, Cincinnati, Ohio 45224, United States ∥ Modeling and Simulation/Computational Chemistry, The Procter & Gamble Company, 8611 Beckett Road, West Chester, Ohio 45069, United States *S Supporting Information ABSTRACT: We have measured and characterized how three classes of surface-active molecules self-assemble at, and modulate the interfacial forces between, a negatively charged mica surface and a hydrophobic end-grafted polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) polymer surface in solution. We provide a broad overview of how chemical and structural properties of surfactant molecules result in different self-assembled structures at polymer and mineral surfaces, by studying three characteristic surfactants: (1) an anionic aliphatic surfactant, sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), (2) a cationic aliphatic surfactant, myristyltrimethylammonium bro- mide (MTAB), and (3) a silicone polyelectrolyte with a long-chain PDMS midblock and multiple cationic end groups. -

Unix Programmer's Manual

There is no warranty of merchantability nor any warranty of fitness for a particu!ar purpose nor any other warranty, either expressed or imp!ied, a’s to the accuracy of the enclosed m~=:crials or a~ Io ~helr ,~.ui~::~::.j!it’/ for ~ny p~rficu~ar pur~.~o~e. ~".-~--, ....-.re: " n~ I T~ ~hone Laaorator es 8ssumg$ no rO, p::::nS,-,,.:~:y ~or their use by the recipient. Furln=,, [: ’ La:::.c:,:e?o:,os ~:’urnes no ob~ja~tjon ~o furnish 6ny a~o,~,,..n~e at ~ny k:nd v,,hetsoever, or to furnish any additional jnformstjcn or documenta’tjon. UNIX PROGRAMMER’S MANUAL F~ifth ~ K. Thompson D. M. Ritchie June, 1974 Copyright:.©d972, 1973, 1974 Bell Telephone:Laboratories, Incorporated Copyright © 1972, 1973, 1974 Bell Telephone Laboratories, Incorporated This manual was set by a Graphic Systems photo- typesetter driven by the troff formatting program operating under the UNIX system. The text of the manual was prepared using the ed text editor. PREFACE to the Fifth Edition . The number of UNIX installations is now above 50, and many more are expected. None of these has exactly the same complement of hardware or software. Therefore, at any particular installa- tion, it is quite possible that this manual will give inappropriate information. The authors are grateful to L. L. Cherry, L. A. Dimino, R. C. Haight, S. C. Johnson, B. W. Ker- nighan, M. E. Lesk, and E. N. Pinson for their contributions to the system software, and to L. E. McMahon for software and for his contributions to this manual. -

Unix Programmer's Manual

- UNIX PROGRAMMER'S MANUAL Sixth Edition K. Thompson D. M. Ritchie May, 1975 - This manual was set by a Graphic Systems phototypeset- ter driven by the troff formatting program operating un- der the UNIX system. The text of the manual was pre- pared using the ed text editor. - PREFACE to the Sixth Edition We are grateful to L. L. Cherry, R. C. Haight, S. C. Johnson, B. W. Kernighan, M. E. Lesk, and E. N. Pin- son for their contributions to the system software, and to L. E. McMahon for software and for his contribu- tions to this manual. We are particularly appreciative of the invaluable technical, editorial, and administra- tive efforts of J. F. Ossanna, M. D. McIlroy, and R. Morris. They all contributed greatly to the stock of UNIX software and to this manual. Their inventiveness, thoughtful criticism, and ungrudging support in- creased immeasurably not only whatever success the UNIX system enjoys, but also our own enjoyment in its creation. i - INTRODUCTION TO THIS MANUAL This manual gives descriptions of the publicly available features of UNIX. It provides neither a general overview ߝ see ‘‘The UNIX Time-sharing System’’ (Comm. ACM 17 7, July 1974, pp. 365-375) for that ߝ nor details of the implementation of the system, which remain to be disclosed. Within the area it surveys, this manual attempts to be as complete and timely as possible. A conscious de- cision was made to describe each program in exactly the state it was in at the time its manual section was prepared. In particular, the desire to describe something as it should be, not as it is, was resisted.