Economic History Association

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

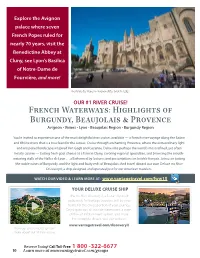

French Waterways: Highlights of Burgundy, Beaujolais & Provence

Explore the Avignon palace where seven French Popes ruled for nearly 70 years, visit the Benedictine Abbey at Cluny, see Lyon’s Basilica of Notre-Dame de Fourvière, and more! The Palais des Popes in Avignon dates back to 1252. OUR #1 RIVER CRUISE! French Waterways: Highlights of Burgundy, Beaujolais & Provence Avignon • Viviers • Lyon • Beaujolais Region • Burgundy Region You’re invited to experience one of the most delightful river cruises available — a French river voyage along the Saône and Rhône rivers that is a true feast for the senses. Cruise through enchanting Provence, where the extraordinary light and unspoiled landscapes inspired Van Gogh and Cezanne. Delve into perhaps the world’s most refined, yet often hearty cuisine — tasting fresh goat cheese at a farm in Cluny, savoring regional specialties, and browsing the mouth- watering stalls of the Halles de Lyon . all informed by lectures and presentations on la table français. Join us in tasting the noble wines of Burgundy, and the light and fruity reds of Beaujolais. And travel aboard our own Deluxe ms River Discovery II, a ship designed and operated just for our American travelers. WATCH OUR VIDEO & LEARN MORE AT: www.vantagetravel.com/fww15 Additional Online Content YOUR DELUXE CRUISE SHIP Facebook The ms River Discovery II, a 5-star ship built exclusively for Vantage travelers, will be your home for the cruise portion of your journey. Enjoy spacious, all outside staterooms, a state- of-the-art infotainment system, and more. For complete details, visit our website. www.vantagetravel.com/discoveryII View our online video to learn more about our #1 river cruise. -

Burgundy Beaujolais

The University of Kentucky Alumni Association Springtime in Provence Burgundy ◆ Beaujolais Cruising the Rhône and Saône Rivers aboard the Deluxe Small River Ship Amadeus Provence May 15 to 23, 2019 RESERVE BY SEPTEMBER 27, 2018 SAVE $2000 PER COUPLE Dear Alumni & Friends: We welcome all alumni, friends and family on this nine-day French sojourn. Visit Provence and the wine regions of Burgundy and Beaujolais en printemps (in springtime), a radiant time of year, when woodland hillsides are awash with the delicately mottled hues of an impressionist’s palette and the region’s famous flora is vibrant throughout the enchanting French countryside. Cruise for seven nights from Provençal Arles to historic Lyon along the fabled Rivers Rhône and Saône aboard the deluxe Amadeus Provence. During your intimate small ship cruise, dock in the heart of each port town and visit six UNESCO World Heritage sites, including the Roman city of Orange, the medieval papal palace of Avignon and the wonderfully preserved Roman amphitheater in Arles. Tour the legendary 15th- century Hôtel-Dieu in Beaune, famous for its intricate and colorful tiled roof, and picturesque Lyon, France’s gastronomique gateway. Enjoy an excursion to the Beaujolais vineyards for a private tour, world-class piano concert and wine tasting at the Château Montmelas, guided by the châtelaine, and visit the Burgundy region for an exclusive tour of Château de Rully, a medieval fortress that has belonged to the family of your guide, Count de Ternay, since the 12th century. A perennial favorite, this exclusive travel program is the quintessential Provençal experience and an excellent value featuring a comprehensive itinerary through the south of France in full bloom with springtime splendor. -

Albret, Jean D' Entries Châlons-En-Champagne (1487)

Index Abbeville 113, 182 Albret, Jean d’ Entries Entries Charles de Bourbon (1520) 183 Châlons-en-Champagne (1487) 181 Charles VIII (1493) 26–27, 35, 41, Albret, Jeanne d’ 50–51, 81, 97, 112 Entries Eleanor of Austria (1531) 60, 139, Limoges (1556) 202 148n64, 160–61 Alençon, Charles, duke of (d.1525) 186, Henry VI (1430) 136 188–89 Louis XI (1463) 53, 86n43, 97n90 Almanni, Luigi 109 Repurchased by Louis XI (1463) 53 Altars 43, 44 Abigail, wife of King David 96 Ambassadors 9–10, 76, 97, 146, 156 Albon de Saint André, Jean d’ 134 Amboise 135, 154 Entries Amboise, Edict of (1563) 67 Lyon (1550) 192, 197, 198–99, 201, 209, Amboise, Georges d’, cardinal and archbishop 214 of Rouen (d.1510) 64–65, 130, 194 Abraham 96 Entries Accounts, financial 15, 16 Noyon (1508) 204 Aeneas 107 Paris (1502) 194 Agamemnon 108 Saint-Quentin (1508) 204 Agen Amelot, Jacques-Charles 218 Entries Amiens 143, 182 Catherine de Medici (1578) 171 Bishop of Charles IX (1565) 125–26, 151–52 Entries Governors 183–84 Nicholas de Pellevé (1555) 28 Oath to Louis XI 185 Captain of 120 Preparing entry for Francis I (1542) 79 Claubaut family 91 Agricol, Saint 184 Confirmation of liberties at court 44, Aire-sur-la-Lys 225 63–64 Aix-en-Provence Entries Confirmation of liberties at court 63n156 Anne of Beaujeu (1493) 105, 175 Entries Antoine de Bourbon (1541) 143, 192, Charles IX (1564) 66n167 209 Bernard de Nogaret de La Valette (1587) Charles VI and Dauphin Louis (1414) 196n79 97n90, 139, 211n164 Françoise de Foix-Candale (1547) Léonor dʼOrléans, duke of Longueville 213–14 (1571) -

Eurostar, the High-Speed Passenger Rail Service from the United Kingdom to Lille, Paris, Brussels And, Today, Uniquely, to Cannes

YOU R JOU RN EY LONDON TO CANNES . THE DAVINCI ONLYCODEIN cinemas . LONDON WATERLOO INTERNATIONAL Welcome to Eurostar, the high-speed passenger rail service from the United Kingdom to Lille, Paris, Brussels and, today, uniquely, to Cannes . Eurostar first began services in 1994 and has since become the air/rail market leader on the London-Paris and London-Brussels routes, offering a fast and seamless travel experience. A Eurostar train is around a quarter of a mile long, and carries up to 750 passengers, the equivalent of twojumbojets. 09 :40 Departure from London Waterloo station. The first part of ourjourney runs through South-East London following the classic domestic line out of the capital. 10:00 KENT REGION Kent is the region running from South-East London to the white cliffs of Dover on the south-eastern coast, where the Channel Tunnel begins. The beautiful rolling countryside and fertile lands of the region have been the backdrop for many historical moments. It was here in 55BC that Julius Caesar landed and uttered the famous words "Veni, vidi, vici" (1 came, l saw, 1 conquered). King Henry VIII first met wife number one, Anne of Cleaves, here, and his chieffruiterer planted the first apple and cherry trees, giving Kent the title of the 'Garden ofEngland'. Kent has also served as the setting for many films such as A Room with a View, The Secret Garden, Young Sherlock Holmes and Hamlet. 10:09 Fawkham Junction . This is the moment we change over to the high-speed line. From now on Eurostar can travel at a top speed of 186mph (300km/h). -

The Crisis of the Seventeenth Century - Thecrisisof the Seventeenth Century

The Crisis of the Seventeenth Century - TheCrisisof the Seventeenth Century , , HUGH TREVOR-ROPER LIBERTY FUND This book is published by Liberty Fund, Inc., a foundation established to en- courage study of the ideal of a society of free and responsible individuals. The cuneiform inscription that serves as our logo and as the design motif for our endpapers is the earliest-known written appearance of the word ‘‘freedom’’ (amagi), or ‘‘liberty.’’ It is taken from a clay document written about 2300 .. in the Sumerian city-state of Lagash. © 1967 by Liberty Fund, Inc. Allrightsreserved Printed in the United States of America Frontispiece © 1999 by Ellen Warner 0504030201C54321 0504030201P54321 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Trevor-Roper, H. R. (Hugh Redwald), 1914– The crisis of the seventeenth century / H.R. Trevor-Roper. p. cm. Originally published: New York: Harper & Row, 1967. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-86597-274-5 (alk. paper)—ISBN 0-86597-278-8 (pbk.: alk. paper) 1. Europe—History—17th century. I. Title: Crisis of the 17th century. II. Title. D246.T75 2001 940.2'52—dc21 00-025945 Liberty Fund, Inc. 8335 Allison Pointe Trail, Suite 300 Indianapolis, Indiana 46250-1684 vii ix 1 Religion, the Reformation, and Social Change 1 2 TheGeneralCrisisoftheSeventeenth Century 43 3 The European Witch-craze of the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries 83 4 The Religious Origins of the Enlightenment 179 5 Three Foreigners: The Philosophers of the Puritan Revolution 219 6 The Fast Sermons of the Long Parliament 273 7 Oliver Cromwell and His Parliaments 317 8 Scotland and the Puritan Revolution 359 9 The Union of Britain in the Seventeenth Century 407 427 v Louis de Geer at the age of sixty-two. -

L'atelier Du Canut Lyonnais

L’ATELIER DU CANUT LYONNAIS AU XIX° SIECLE Par Philippe DEMOULE ©2002 INTRODUCTION La soierie lyonnaise a contribué pendant plusieurs siècles à porter la renommée d’une région au-delà des océans. De très nombreux documents sont restés qui décrivent cette activité, d’un point de vue historique ou sociologique et notre ambition n’est pas d’aborder le sujet sous l’un de ces angles, d’autres, certainement plus compétents que nous ont contribué à cette mémoire collective. Nous avons voulu traiter un autre aspect de ce thème qui nous tient bien plus à cœur et que nous connaissons mieux. Nous aborderons dans cet ouvrage l’angle de la mémoire technologique. Nous avons constaté que hormis quelques ouvrages extrêmement rares en langue française comme le Traité des tissus de Falcot 1 (1844) ou l’Art du fabricant de soieries de Paulet 1 (1777), aucun ouvrage technique ne traite de l’atelier du canut lyonnais au XIX° siècle. L’Encyclopédie de Diderot et d’Alembert, tout comme le Paulet, pour intéressants qu’ils soient, décrivent une technologie antérieure à celle qui nous concerne, et de plus ne nous ont pas semblé aborder les choses suffisamment en profondeur. Notre volonté est de limiter le champ de nos propos mais de les développer le plus complètement possible. Le CVMT, Conservatoire des Vieux Métiers du Textile a choisi, dans le cadre de sa mission de sauvegarde de tenter de combler cette lacune en rédigeant cet ouvrage dont le contenu n’a pas été défini au hasard mais dans la perspective de contribuer à mettre à la disposition du public le plus large possible une description précise et abondamment illustrée de l’atelier du canut lyonnais et de quelques techniques de tissage de soieries. -

Jurisprudence Administrative

Jurisprudence administrative. I. Attributions municipales : Toulouse. XVIIe siècle. Resp Pf pl A 0069 (9 doc.) : Lettres générales authentiques & perpétuel privilèges d’Ecorniflerie soit pour l’entrée ou issue de quelques repas que ce soit : Lettres générales. Authentique & perpétuel privilège d’écorniflerie, soit pour l’entrée ou issue de quelque repas que ce soit / Signé, Bachus. Et plus bas, Engorgevin. – s.l. : s.n., s.d. – 1 placard ; justif. 300 x 180 mm. Resp Pf pl A 0069/1 Tableau des Capitouls pour l’année 1668 : Messieurs les anciens Capitouls de robe longue. 1668 finissant 1669. Messieurs les anciens Capitouls de robe courte / Clausolle greffier & secretaire. – [Toulouse] : s.n., [1669]. – 1 placard : frise gr.s.b. ; justif. 380 x 300 mm. Resp Pf pl A 0069/2 Lettres patentes qui confirment la noblesse des Capitouls, 1692 : Lettres patentes, qui confirment les Capitouls de Toulouse & leurs descendants, dans leurs priviléges de noblesse. – [Toulouse] : s.n., [1692]. – 4 p. : bandeau et lettre ornée gr.s.b. ; 2°. Resp Pf pl A 0069/3 Hotel de ville – Autorisation de l’intendant d’emprunter 250 000 livres, 1692 : Extrait du registre des délibérations de l’hotel de ville de Toulouse / Claussolles. – [Toulouse] : s.n., [1692]. – 4 p. : bandeaux et lettre ornée gr.s.b. ; 2°. Resp Pf pl A 0069/4 Ordonnance des Capitouls : Enlèvement des boues & immondices que le passage de Sa Majesté a laissé à Toulouse, 1660 : Ordonnance de Messieurs les Capitouls de Tolose. – [Toulouse] : s.n., [1660]. – 1 placard : armes et lettre ornée gr.s.b. ; justif. : 320 x 240 mm. Resp Pf pl A 0069/5 Délais des assignations compétantes que doivent estre données en la cour de parlement de Tolose, par seneschaussées & judicature avec les surceances d’icelles, obtenues au greffe des presentations de ladite cour. -

The Palace of Versailles, Self-Fashioning, and the Coming of the French Revolution

La Belle et la Bête: The Palace of Versailles, Self-Fashioning, and the Coming of the French Revolution La Belle et la Bête: The Palace of Versailles, Self-Fashioning, and the Coming of the French Revolution Savanna R. Teague Abstract While the mass consumption of luxury items is oftentimes described as a factor leading the Third Estate to take action against the First and Second Estates in the buildup to the French Revolution, that spending is presented as little more than salt in the open wounds of a starving and ever-growing population that had been growing evermore destitute since the beginnings of the early modern era. However, the causes and contexts of the conspicuous consumption as practiced by the aristocracy reveal how they directly correlate to the social tensions that persisted throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries until they erupted in the 1790s. The isolation and the dictation of taste and style that Louis XIV commanded through Versailles and State-run luxury workshops became commonplace within a generation after the Fronde in which the nobles had engaged during the previous century. Versailles allowed the new generation of the aristocracy to be placated with petty privileges that developed out of the rigorous court etiquette, and their conspicuous consumption only increased as the need to compete with others at Court and those newly ennobled continued. This study examines a materialistic culture alongside its material culture, focusing on explaining the expenditures of the aristocracy without becoming enamored by the spectacle of wealth itself. The goods and services that the French aristocracy indulged in purchasing were not simply marks of luxury; they represented social ideals about order and privilege. -

French Wine Scholar

French Wine Scholar Detailed Curriculum The French Wine Scholar™ program presents each French wine region as an integrated whole by explaining the impact of history, the significance of geological events, the importance of topographical markers and the influence of climatic factors on the wine in the the glass. No topic is discussed in isolation in order to give students a working knowledge of the material at hand. FOUNDATION UNIT: In order to launch French Wine Scholar™ candidates into the wine regions of France from a position of strength, Unit One covers French wine law, grape varieties, viticulture and winemaking in-depth. It merits reading, even by advanced students of wine, as so much has changed-- specifically with regard to wine law and new research on grape origins. ALSACE: In Alsace, the diversity of soil types, grape varieties and wine styles makes for a complicated sensory landscape. Do you know the difference between Klevner and Klevener? The relationship between Pinot Gris, Tokay and Furmint? Can you explain the difference between a Vendanges Tardives and a Sélection de Grains Nobles? This class takes Alsace beyond the basics. CHAMPAGNE: The champagne process was an evolutionary one not a revolutionary one. Find out how the method developed from an inexpert and uncontrolled phenomenon to the precise and polished process of today. Learn why Champagne is unique among the world’s sparkling wine producing regions and why it has become the world-class luxury good that it is. BOURGOGNE: In Bourgogne, an ancient and fractured geology delivers wines of distinction and distinctiveness. Learn how soil, topography and climate create enough variability to craft 101 different AOCs within this region’s borders! Discover the history and historic precedent behind such subtle and nuanced fractionalization. -

Violence in Reformation France Christopher M

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette Maria Dittman Library Research Competition: Library (Raynor Memorial Libraries) Student Award Winners 4-1-2010 Quel Horreur!: Violence in Reformation France Christopher M. McFadin Marquette University, [email protected] Undergraduate recipient (Junior/Senior category) of the Library's Maria Dittman Award, Spring 2010. Paper written for History 4995 (Independent Study) with Dr. Julius Ruff. © Christopher M. McFadin 1 Quel horreur! : Violence in Reformation France By Chris McFadin History 4995: Independent Study on Violence in the French Wars of Religion, 1562-1629 Dr. Julius Ruff November 9, 2009 2 Oh happy victory! It is to you alone Lord, not to us, the distinguished trophy of honor. In one stroke you tore up the trunk, and the root, and the strewn earth of the heretical vermin. Vermin, who were caught in snares that they had dared to set for your faithful subjects. Oh favorable night! Hour most desirable in which we placed our hope. 1 Michel de Roigny, On the St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre, 1572 The level of sectarian violence that erupted in Reformation France was extraordinary. Otherwise ordinary Catholics tortured their Huguenot neighbors to death and then afterwards mutilated their corpses, sometimes feeding the disfigured remains to farm animals. Catholic children elicited applause from their coreligionists as they killed adult Huguenots by tearing them to pieces. Huguenots assaulted Catholic priests during the Mass, pillaged Catholic churches, and desecrated the Host. Indeed, as the sectarian duel increased in frequency and intensity, a man could be killed for calling someone a Huguenot; both sides used religion to rationalize the assassinations of dukes and kings. -

France: Vineyards of Beaujolais

VBT Itinerary by VBT www.vbt.com France: Vineyards of Beaujolais Bike Vacation + Air Package Imagine cycling into the tranquil heart of Beaujolais, where the finest wines and most sublime cuisine greet you at every turn. Our inn-to-inn Self-Guided Bicycling Vacation through Beaujolais wine country reveals this storied region, with a wide choice of rides on traffic-free rural roads, through gently rolling vineyards and into authentic, timeless villages. Coast into Chardonnay, where the namesake wine was born. Explore the charming hamlets of Pouilly-Fuissé, Saint-Amour and Romaneche-Thorins. Step back in time as you explore prehistoric sites, Roman ruins, the medieval abbey of Cluny and villages carved from golden-hued stone. Along the way, experience memorable stays at a boutique city hotel and at stunning historic châteaux, where surrounding vineyards produce delicious wines and award-winning chefs serve the finest in French gastronomy. Cultural Highlights 1 / 10 VBT Itinerary by VBT www.vbt.com Cycle among the iconic vineyards of Beaujolais, coasting through charming wine villages producing some of France’s great wines Explore the renowned wine appellations and stunning stone villages of Pouilly-Fuissé, Saint- Amour and Romaneche-Thorins Ride into Cluny, once the world’s epicenter of Christianity, and view its 10th-century abbey Pedal to the Rock of Solutré, a striking limestone outcropping towering over vineyards and a favorite walking destination of former President Mitterand Take a spin among Southern Beaujolais’ 15th-century villages of golden stone, the Pierres dorées, constructed of luminescent limestone Sample fine Chardonnays when you pause in the village that gave the white wine its name Savor the luxurious amenities and stunning settings of two four-star Beaujolais chateaux, where gourmet meals and home-produced wines elevate your vacation What to Expect This tour offers a combination of easy terrain and moderate hills and is ideal for beginner and experienced cyclists. -

Page 31 H-France Review Vol. 6 (January 2006), No. 6 Ralph E

H-France Review Volume 6 (2006) Page 31 H-France Review Vol. 6 (January 2006), No. 6 Ralph E. Giesey, Rulership in France, 15th-17th Centuries. Variorum Collected Studies Series CS794. Aldershot, Hamps. and Burlington, Vt.: Ashgate, 2004. xii + 336 pp. Figures, notes, and index. $109.95 U.S./£57.50 U.K. (cl). ISBN 0-86078-920-9. Review by Jotham Parsons, Duquesne University. The volumes of the Variorum Collected Studies Series are not among the cheapest of academic books, but they are often among the most satisfying. A comprehensive collection of a scholar’s articles is more than just a handy reference work, saving one the trouble of tracking down obscure journals, conference proceedings, and Festschriften. In some respects, it is more valuable, or at least more revealing, than a collection of the same scholar’s monographs, for it gives the reader a much more complete and higher- resolution picture of the interests, influences, and exogenous forces that shape an academic career. Such is certainly the case with the present collection of Ralph Giesey’s articles, spanning a period of nearly forty years. They testify to the breadth of the author’s interests, ranging from the fifteenth to the eighteenth centuries and from royal ceremonial to family property to the glosses of the civil law. They also reveal a unifying ambition, though: to understand old-regime France through its laws and legal thinkers. In pursuing that ambition, Giesey has had fewer peers than one might have thought, and fewer followers than one might have hoped. Professor Giesey was a student of Ernst Kantorowicz, perhaps the twentieth century’s most profound student of the pre-modern European political imagination.