My Name Is Jing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Phoenix Films 1999-2019/20 Sorted by Film Title 10

Phoenix Films 1999-2019/20 Sorted by Film Title Film Date Rating(%) 2046 1-Feb-2006 68 120BPM (Beats Per Minute) 24-Oct-2018 75 3 Coeurs 14-Jun-2017 64 35 Shots of Rum 13-Jan-2010 65 45 Years 20-Apr-2016 83 5 x 2 3-May-2006 65 A Bout de Souffle 23-May-2001 60 A Clockwork Orange 8-Nov-2000 81 A Fantastic Woman 3-Oct-2018 84 A Farewell to Arms 19-Nov-2014 70 A Highjacking 22-Jan-2014 92 A Late Quartet 15-Jan-2014 86 A Man Called Ove 8-Nov-2017 90 A Matter of Life and Death 7-Mar-2001 80 A One and A Two 23-Oct-2001 79 A Prairie Home Companion 19-Dec-2007 79 A Private War 15-May-2019 94 A Room and a Half 30-Mar-2011 75 A Royal Affair 3-Oct-2012 92 A Separation 21-Mar-2012 85 A Simple Life 8-May-2013 86 A Single Man 6-Oct-2010 79 A United Kingdom 22-Nov-2017 90 A Very Long Engagement 8-Jun-2005 80 A War 15-Feb-2017 91 A White Ribbon 21-Apr-2010 75 Abouna 3-Dec-2003 75 About Elly 26-Mar-2014 78 Accident 22-May-2002 72 After Love 14-Feb-2018 76 After the Storm 25-Oct-2017 77 After the Wedding 31-Oct-2007 86 Alice et Martin 10-May-2000 All About My Mother 11-Oct-2000 84 All the Wild Horses 22-May-2019 88 Almanya: Welcome To Germany 19-Oct-2016 88 Amal 14-Apr-2010 91 American Beauty 18-Oct-2000 83 American Honey 17-May-2017 67 American Splendor 9-Mar-2005 78 Amores Perros 7-Nov-2001 85 Amour 1-May-2013 85 Amy 8-Feb-2017 90 An Autumn Afternoon 2-Mar-2016 66 An Education 5-May-2010 86 Anna Karenina 17-Apr-2013 82 Another Year 2-Mar-2011 86 Apocalypse Now Redux 30-Jan-2002 77 Apollo 11 20-Nov-2019 95 Apostasy 6-Mar-2019 82 Aquarius 31-Jan-2018 73 -

Distribution Agreement in Presenting This

Distribution Agreement In presenting this thesis or dissertation as a partial fulfillment of the requirements for an advanced degree from Emory University, I hereby grant to Emory University and its agents the non-exclusive license to archive, make accessible, and display my thesis or dissertation in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known, including display on the world wide web. I understand that I may select some access restrictions as part of the online submission of this thesis or dissertation. I retain all ownership rights to the copyright of the thesis or dissertation. I also retain the right to use in future works (such as articles or books) all or part of this thesis or dissertation. Signature: _____________________________ ______________ Tianyi Yao Date Crime and History Intersect: Films of Murder in Contemporary Chinese Wenyi Cinema By Tianyi Yao Master of Arts Film and Media Studies _________________________________________ Matthew Bernstein Advisor _________________________________________ Tanine Allison Committee Member _________________________________________ Timothy Holland Committee Member _________________________________________ Michele Schreiber Committee Member Accepted: _________________________________________ Lisa A. Tedesco, Ph.D. Dean of the James T. Laney School of Graduate Studies ___________________ Date Crime and History Intersect: Films of Murder in Contemporary Chinese Wenyi Cinema By Tianyi Yao B.A., Trinity College, 2015 Advisor: Matthew Bernstein, M.F.A., Ph.D. An abstract of -

Mountains May Depart

presents MOUNTAINS MAY DEPART A film by JIA ZHANGKE 2015 Cannes Film Festival 2015 Toronto International Film Festival 2015 New York Film Festival China, Japan, France | 131 minutes | 2015 www.kinolorber.com Kino Lorber, Inc. 333 West 39th St. Suite 503 New York, NY 10018 (212) 629-6880 Publicity Contact: Rodrigo Brandao, [email protected] O: (212) 629-6880 Synopsis China, 1999. In Fenyang, childhood friends Liangzi, a coal miner, and Zhang, the owner of a gas station, are both in love with Tao, the town beauty. Tao eventually marries the wealthier Zhang and they have a son he names Dollar. 2014. Tao is divorced and her son emigrates to Australia with his business magnate father. Australia, 2025. 19-year-old Dollar no longer speaks Chinese and can barely communicate with his now bankrupt father. All that he remembers of his mother is her name…. Director’s Statement It’s because I’ve experienced my share of ups and downs in life that I wanted to make Mountains May Depart. This film spans the past, the present and the future, going from 1999 to 2014 and then to 2025. China’s economic development began to skyrocket in the 1990s. Living in this surreal economic environment has inevitably changed the ways that people deal with their emotions. The impulse behind this film is to examine the effect of putting financial considerations ahead of emotional relationships. If we imagine a point ten years into our future, how will we look back on what’s happening today? And how will we understand “freedom”? Buddhist thought sees four stages in the flow of life: birth, old age, sickness, and death. -

MOUNTAINS MAY DEPART (SHAN HE GU REN) a Film by Jia Zhangke

MOUNTAINS MAY DEPART (SHAN HE GU REN) A film by Jia Zhangke In Competition Cannes Film Festival 2015 China/Japan/France 2015 / 126 minutes / Mandarin with English subtitles / cert. tbc Opens in cinemas Spring 2016 FOR ALL PRESS ENQUIRIES PLEASE CONTACT Sue Porter/Lizzie Frith – Porter Frith Ltd Tel: 020 7833 8444/E‐mail: [email protected] FOR ALL OTHER ENQUIRIES PLEASE CONTACT Robert Beeson – New Wave Films [email protected] New Wave Films 1 Lower John Street London W1F 9DT Tel: 020 3603 7577 www.newwavefilms.co.uk SYNOPSIS China, 1999. In Fenyang, childhood friends Liangzi, a coal miner, and Zhang, the owner of a gas station, are both in love with Tao, the town beauty. Tao eventually marries the wealthier Zhang and they have a son he names Dollar. 2014. Tao is divorced meets up with her son before he emigrates to Australia with his business magnate father. Australia, 2025. 19-year-old Dollar no longer speaks Chinese and can barely communicate with his now bankrupt father. All that he remembers of his mother is her name... DIRECTOR’S NOTE It’s because I’ve experienced my share of ups and downs in life that I wanted to make Mountains May Depart. This film spans the past, the present and the future, going from 1999 to 2014 and then to 2025. China’s economic development began to skyrocket in the 1990s. Living in this surreal economic environment has inevitably changed the ways that people deal with their emotions. The impulse behind this film is to examine the effect of putting financial considerations ahead of emotional relationships. -

Index to Volume 29 January to December 2019 Compiled by Patricia Coward

THE INTERNATIONAL FILM MAGAZINE Index to Volume 29 January to December 2019 Compiled by Patricia Coward How to use this Index The first number after a title refers to the issue month, and the second and subsequent numbers are the page references. Eg: 8:9, 32 (August, page 9 and page 32). THIS IS A SUPPLEMENT TO SIGHT & SOUND SUBJECT INDEX Film review titles are also Akbari, Mania 6:18 Anchors Away 12:44, 46 Korean Film Archive, Seoul 3:8 archives of television material Spielberg’s campaign for four- included and are indicated by Akerman, Chantal 11:47, 92(b) Ancient Law, The 1/2:44, 45; 6:32 Stanley Kubrick 12:32 collected by 11:19 week theatrical release 5:5 (r) after the reference; Akhavan, Desiree 3:95; 6:15 Andersen, Thom 4:81 Library and Archives Richard Billingham 4:44 BAFTA 4:11, to Sue (b) after reference indicates Akin, Fatih 4:19 Anderson, Gillian 12:17 Canada, Ottawa 4:80 Jef Cornelis’s Bruce-Smith 3:5 a book review; Akin, Levan 7:29 Anderson, Laurie 4:13 Library of Congress, Washington documentaries 8:12-3 Awful Truth, The (1937) 9:42, 46 Akingbade, Ayo 8:31 Anderson, Lindsay 9:6 1/2:14; 4:80; 6:81 Josephine Deckers’s Madeline’s Axiom 7:11 A Akinnuoye-Agbaje, Adewale 8:42 Anderson, Paul Thomas Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), Madeline 6:8-9, 66(r) Ayeh, Jaygann 8:22 Abbas, Hiam 1/2:47; 12:35 Akinola, Segun 10:44 1/2:24, 38; 4:25; 11:31, 34 New York 1/2:45; 6:81 Flaherty Seminar 2019, Ayer, David 10:31 Abbasi, Ali Akrami, Jamsheed 11:83 Anderson, Wes 1/2:24, 36; 5:7; 11:6 National Library of Scotland Hamilton 10:14-5 Ayoade, Richard -

I WISH I KNEW a Film by Jia Zhangke

presents I WISH I KNEW A film by Jia Zhangke **Official Selection, Un Certain Regard, Cannes Film Festival 2010** **Official Selection, Locarno Film Festival 2010** **Official Selection, Toronto International Film Festival, 2010** China / 2010 / 118 minutes / Color / Chinese with English subtitles Publicity Contacts: David Ninh, [email protected] Distributor Contact: Chris Wells, [email protected] Kino Lorber, Inc. 333 West 39th St., Suite 503 New York, NY 10018 (212) 629-6880 Short Synopsis: Shanghai, a fast-changing metropolis, a port city where people come and go. Eighteen people recall their lives in Shanghai. Their personal experiences, like eighteen chapters of a novel, builds a vivid picture of Shanghai life from the 1930s to 2010. Long Synopsis: Shanghai's past and present flow together in Jia Zhangke's poetic and poignant portrait of this fast-changing port city. Restoring censored images and filling in forgotten facts, Jia provides an alternative version of 20th century China's fraught history as reflected through life in the Yangtze city. He builds his narrative through a series of eighteen interviews with people from all walks of life-politicians' children, ex-soldiers, criminals, and artists (including Taiwanese master Hou Hsiao-hsien) -- while returning regularly to the image of his favorite lead actress, Zhao Tao, wandering through the Shanghai World Expo Park. (The film was commissioned by the World Expo, but is anything but a piece of straightforward civic boosterism.) A richly textured tapestry full of provocative juxtapositions. - Metrograph Director’s Biography: Jia Zhangke was born in Fenyang, Shanxi, in 1970 and graduated from Beijing Film Academy. -

The Individual and the Crowd in Jia Zhangke's Films Jung Koo Kim A

Goldsmiths College University of London Cinema of Paradox: The Individual and the Crowd in Jia Zhangke’s Films Jung Koo Kim A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy to the department of Media and Communications August 2016 1 DECLARATION I hereby declare that this submission is my own work and that, to the best of my knowledge and belief, it contains no material previously published or written by another person nor material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma of the university or other institute of higher learning, except where due acknowledgment has been made in the text. Signed…… …………… Date….…10-Aug.-2016…… 2 ABSTRACT This thesis attempts to understand Chinese film director Jia Zhangke with the concept of “paradox.” Challenging the existing discussions on Jia Zhangke, which have been mainly centered around an international filmmaker to represent Chinese national cinema or an auteur to construct realism in post-socialist China, I focus on how he deals with the individual and the crowd to read through his oeuvre as “paradox.” Based on film text analysis, my discussion develops in two parts: First, the emergence of the individual subject from his debut feature film Xiao Wu to The World; and second, the discovery of the crowd from Still Life to his later documentary works such as Dong and Useless. The first part examines how the individual is differentiated from the crowd in Jia’s earlier films under the Chinese social transformation during the 1990s and 2000s. For his predecessors, the collective was central not only in so-called “leitmotif” (zhuxuanlü or propaganda) films to enhance socialist ideology, but also in Fifth Generation films as “national allegory.” However, what Jia pays attention to is “I” rather than “We.” He focuses on the individual, marginal characters, and the local rather than the collective, heroes, and the national. -

Uvic Thesis Template

A People’s Director: Jia Zhangke’s Cinematic Style by Yaxi Luo Bachelor of Arts, Sichuan University, 2014 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of Pacific and Asian Studies Yaxi Luo, 2017 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. ii Supervisory Committee A People’s Director: Jia Zhangke’s Cinematic Style by Yaxi Luo Bachelor of Arts, Sichuan University, 2014 Supervisory Committee Dr. Richard King, (Department of Pacific and Asian Studies) Supervisor Dr. Michael Bodden, (Department of Pacific and Asian Studies) Departmental Member iii Abstract Supervisory Committee Dr. Richard King, (Department of Pacific and Asian Studies) Supervisor Dr. Michael Bodden, (Department of Pacific and Asian Studies) Departmental Member ABSTRACT As a leading figure of “The Six Generation” directors, Jia Zhangke’s films focus on reality of contemporary Chinese society, and record the lives of people who were left behind after the country’s urbanization process. He depicts a lot of characters who struggle with their lives, and he works to explore one common question throughout all of his films: “where do I belong?” Jia Zhangke uses unique filmmaking techniques in order to emphasize the feelings of people losing their sense of home. In this thesis, I am going to analyze his cinematic style from three perspectives: photography, musical scores and metaphors. In each chapter, I will use one film as the main subject of discussion and reference other films to complement my analysis. -

AMC River East 21 312-332-FILM

© Poster Design: Kuo-Crary Tsung-Hui 322 E. Illinois St. AMC River East 21 312-332-FILM Cinema/CHicago Presents 51st Chicago International Oct. 15-29, 2015 Fim Festival FESTIVAL AT A GLANCE chicagofilmfestival.com Clever - p. 17 The 33 - p. 12 Funny Girl - p. 20 Brooklyn - p. 15 A Perfect Day - p. 29 Carol - p. 16 Stinking Heaven - p. 31 Dheepan - p. 18 The Thin Yellow Line - p. 32 dAm I Am Michael - p. 23 Very Semi-Serious - p. 34 I Smile Back - p. 23 Walking Distance - p. 35 James White - p. 24 cMeY We Are Francesco - p. 35 Macbeth - p. 26 Bite - p. 15 All About Them - p. 13 Ludo - p. 26 Big Father, Small Father and Other Stories - p. 14 Other Madnesses - p. 29 Cuckold - p. 18 The Red Spider - p. 30 Neon Bull - p. 28 Tag - p. 32 tRiLe Orphans of Eldorado - p. 28 They Look Like People - p. 32 Tough Love - p. 33 Three Days in September - p. 32 XConfessions: A Conversation With Erika Lust - p. 36 sXy Why Me? - p. 35 CONTENTS 5 Welcome! 42 Travel Guide 7 Tickets & Passes 43 Hot Spots The Birth of Saké - p. 14 10 Opening Night 44 Education Program Breakfast at Ina’s - p. 15 11 Film Program Guide 45 Membership For Grace - p. 20 12-36 Film Guide: A to Z 45 Merchandise Open Tables - p. 28 Sweet Bean - p. 31 36 Closing Night 46-52 Daily Film Schedule 38 Industry Days 53 Film Index by Country fOd 39 Spotlight: Architecture 53 Film Index by Category 39 Panels & Tast of Cinema 54 Film Index by Theme 40 Short Films 55 Festival Partners BecaUse everYboDY loves movies! For over half a century, the Chicago International Film Festival has done our part to expand your cinematic horizons with entertaining, provocative, and illuminating selections from around the globe. -

Mise En Page 1

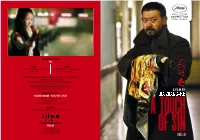

INTERNATIONAL SALES MK2 PARIS CANNES MK2 - 55 rue Traversière FIVE HOTEL - 1 rue Notre-Dame 75012 Paris 06400 Cannes Juliette Schrameck, Head of International Sales & Acquisitions [email protected] Fionnuala Jamison, International Sales Executive [email protected] Victoire Thevenin, International Sales Executive [email protected] A FILM BY INTERNATIONAL PRESS RICHARD LORMAND - FILM ⎮PRESS ⎮PLUS JIA ZHANG-KE www.FilmPressPlus.com [email protected] Tel: +33-9-7044-9865 / +33-6-2424-1654 m IN CANNES o c . s Tel: 08 70 44 98 65 / 06 09 92 55 47 / 06 24 24 16 54 a e r c - l e s k a . w w w : k r o w t XSTREAM PICTURES (BEIJING) r EVA LAM A Tel: +86 10 8235 0984 Fax: +86 10 8235 4938 [email protected] Xstream Pictures (Beijing), Office Kitano Shangai Film Group Corporation & MK2 present A FILM BY JIA ZHANG-KE 133 min / Color / 1:2.4 / 2013 Xstream Pictures (Beijing ) Office Kitano Shanghai Film Group Corporation Present In association with Shanxi Film and Television Group Bandai Visual Bitters End SYNOPSIS DIRECTOR’S NOTE This film is about four deaths, four incidents which actually happened in China in recent years: three murders and one suicide. These incidents are well-known to people throughout China. They happened in Shanxi, Chongqing, Hubei and Guangdong – that is, from the north to the south, spanning much of the country. I wanted to use these news reports to build a comprehensive portrait of life in contemporary China. China is still changing rapidly, in a way that makes the country look more prosperous than before. -

Dlkj;Fdslk ;Lkfdj

JIA ZHANGKE RETROSPECTIVE AT MoMA PRESENTS CONTEMPORARY FILMS THAT REFLECT THE ENORMOUS CHANGES TAKING PLACE IN CHINESE SOCIETY Internationally Celebrated Filmmaker Takes on Complex Subject Matter Using a Combination of Gritty Realism, Elegant Camerawork, and Unique Artistic Vision Jia Zhangke: A Retrospective March 5–20, 2010 The Roy and Niuta Titus Theaters NEW YORK, February 5, 2010—Jia Zhangke: A Retrospective is the first complete U.S. retrospective of this internationally celebrated contemporary filmmaker who, in little more than a decade, has become one of cinema‘s most critically acclaimed artists and the leading figure of the sixth generation of Chinese filmmakers. The exhibition screens in The Roy and Niuta Titus Theaters from March 5 through 20, 2010, and includes Jia Zhangke‘s (Chinese, b. 1970) entire oeuvre: eight features and six shorts, dating from 1995 to 2008. The retrospective is organized by Jytte Jensen, Curator, Department of Film, The Museum of Modern Art. The director will be at MoMA with Zhao Tao—his leading actress since her debut in Zhantai (Platform) (2000)—to introduce most of his films at screenings between the opening night film on Friday, March 5, at 7:00 p.m. of Shijie (The World) (2004), through the screening on Monday, March 8 at 4:00 p.m. of Black Breakfast (2008) and Sanxia haoren (Still Life) (2006). Jia will also participate in a special Modern Mondays event at MoMA on the evening of March 8 at 7:00 p.m., where he will discuss his recent films and present two shorts and a sneak preview of a segment of his upcoming feature, Shanghai Chuan Qi (I Wish I Knew, 2010), followed by a discussion. -

DOCUMENTARY CINEMA and the FICTIONS of REALITY a Project Presented to the Faculty

DOCUMENTARY CINEMA AND THE FICTIONS OF REALITY __________________________________________ A Project Presented to The Faculty of the Graduate School At the University of Missouri-Columbia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts By WILLIAM ANTHONY LINHARES Stacey Woelfel, Project Supervisor DECEMBER 2017 DEDICATION To my parents, Jim and Mary Linhares. Thank you for the unwavering commitment, support and friendship. ACKOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to acknowledge and thank: Stacey Woelfel for his support, commitment and calm in leading me through the practical and creative development of my film. Yours is a calm voice of reason in the otherwise nearly pathological world of documentary filmmaking. Robert Greene for the willingness to offer his perspective (one of the most attuned working in cinema today) and mentorship through the many rough cuts of my film. It has been an honor to work the process with you. Roger Cook for blindly accepting to hop aboard this committee. Your patient, thoughtful advice concerning the first cut of my film was essential to the various evolutions it later embodied. After we met, I completely reworked the entire design of the film. It would not be what it is today without that first meeting. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS DEDICATION……………………………………………………………………………ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS………………………………………………………………iii Chapter 1. INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………….1 2. ACTIVITY LOG……………………………………………………………...3 3. EVALUATION……………………………………………………………...20 4. PHYSICAL EVIDENCE……………………………………………….........24 5. ANALYSIS……………………………………………………………............25 REFERENCES……………………………………………………………......................57 APPENDIX……………………………………………………………............................58 iii Chapter 1: Introduction I chose this project for a variety of reasons, into which both artistic and career- oriented elements factored. First, there was a project. Then there was Docktown.