Program Notes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RUSSIAN, SOVIET & POST-SOVIET SYMPHONIES Composers

RUSSIAN, SOVIET & POST-SOVIET SYMPHONIES A Discography of CDs and LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Composers A-G KHAIRULLO ABDULAYEV (b. 1930, TAJIKISTAN) Born in Kulyab, Tajikistan. He studied composition at the Moscow Conservatory under Anatol Alexandrov. He has composed orchestral, choral, vocal and instrumental works. Sinfonietta in E minor (1964) Veronica Dudarova/Moscow State Symphony Orchestra ( + Poem to Lenin and Khamdamov: Day on a Collective Farm) MELODIYA S10-16331-2 (LP) (1981) LEV ABELIOVICH (1912-1985, BELARUS) Born in Vilnius, Lithuania. He studied at the Warsaw Conservatory and then at the Minsk Conservatory where he studied under Vasily Zolataryov. After graduation from the latter institution, he took further composition courses with Nikolai Miaskovsky at the Moscow Conservatory. He composed orchestral, vocal and chamber works. His other Symphonies are Nos. 1 (1962), 3 in B flat minor (1967) and 4 (1969). Symphony No. 2 in E minor (1964) Valentin Katayev/Byelorussian State Symphony Orchestra ( + Vagner: Suite for Symphony Orchestra) MELODIYA D 024909-10 (LP) (1969) VASIF ADIGEZALOV (1935-2006, AZERBAIJAN) Born in Baku, Azerbaijan. He studied under Kara Karayev at the Azerbaijan Conservatory and then joined the staff of that school. His compositional catalgue covers the entire range of genres from opera to film music and works for folk instruments. Among his orchestral works are 4 Symphonies of which the unrecorded ones are Nos. 1 (1958) and 4 "Segah" (1998). Symphony No. 2 (1968) Boris Khaikin/Moscow Radio Symphony Orchestra (rec. 1968) ( + Piano Concertos Nos. 2 and 3, Poem Exaltation for 2 Pianos and Orchestra, Africa Amidst MusicWeb International Last updated: August 2020 Russian, Soviet & Post-Soviet Symphonies A-G Struggles, Garabagh Shikastasi Oratorio and Land of Fire Oratorio) AZERBAIJAN INTERNATIONAL (3 CDs) (2007) Symphony No. -

Verdi Falstaff

Table of Opera 101: Getting Ready for the Opera 4 A Brief History of Western Opera 6 Philadelphia’s Academy of Music 8 Broad Street: Avenue of the Arts Con9tOperae Etiquette 101 nts 10 Why I Like Opera by Taylor Baggs Relating Opera to History: The Culture Connection 11 Giuseppe Verdi: Hero of Italy 12 Verdi Timeline 13 Make Your Own Timeline 14 Game: Falstaff Crossword Puzzle 16 Bard of Stratford – William Shakespeare 18 All the World’s a Stage: The Globe Theatre Falstaff: Libretto and Production Information 20 Falstaff Synopsis 22 Meet the Artists 23 Introducing Soprano Christine Goerke 24 Falstaff LIBRETTO Behind the Scenes: Careers in the Arts 65 Game: Connect the Opera Terms 66 So You Want to Sing Like an Opera Singer! 68 The Highs and Lows of the Operatic Voice 70 Life in the Opera Chorus: Julie-Ann Whitely 71 The Subtle Art of Costume Design Lessons 72 Conflicts and Loves in Falstaff 73 Review of Philadelphia’s First Falstaff 74 2006-2007 Season Subscriptions Glossary 75 State Standards 79 State Standards Met 80 A Brief History of 4 Western Opera Theatrical performances that use music, song Music was changing, too. and dance to tell a story can be found in many Composers abandoned the ornate cultures. Opera is just one example of music drama. Baroque style of music and began Claudio Monteverdi In its 400-year history opera has been shaped by the to write less complicated music 1567-1643 times in which it was created and tells us much that expressed the character’s thoughts and feelings about those who participated in the art form as writers, more believably. -

My Musical Lineage Since the 1600S

Paris Smaragdis My musical lineage Richard Boulanger since the 1600s Barry Vercoe Names in bold are people you should recognize from music history class if you were not asleep. Malcolm Peyton Hugo Norden Joji Yuasa Alan Black Bernard Rands Jack Jarrett Roger Reynolds Irving Fine Edward Cone Edward Steuerman Wolfgang Fortner Felix Winternitz Sebastian Matthews Howard Thatcher Hugo Kontschak Michael Czajkowski Pierre Boulez Luciano Berio Bruno Maderna Boris Blacher Erich Peter Tibor Kozma Bernhard Heiden Aaron Copland Walter Piston Ross Lee Finney Jr Leo Sowerby Bernard Wagenaar René Leibowitz Vincent Persichetti Andrée Vaurabourg Olivier Messiaen Giulio Cesare Paribeni Giorgio Federico Ghedini Luigi Dallapiccola Hermann Scherchen Alessandro Bustini Antonio Guarnieri Gian Francesco Malipiero Friedrich Ernst Koch Paul Hindemith Sergei Koussevitzky Circa 20th century Leopold Wolfsohn Rubin Goldmark Archibald Davinson Clifford Heilman Edward Ballantine George Enescu Harris Shaw Edward Burlingame Hill Roger Sessions Nadia Boulanger Johan Wagenaar Maurice Ravel Anton Webern Paul Dukas Alban Berg Fritz Reiner Darius Milhaud Olga Samaroff Marcel Dupré Ernesto Consolo Vito Frazzi Marco Enrico Bossi Antonio Smareglia Arnold Mendelssohn Bernhard Sekles Maurice Emmanuel Antonín Dvořák Arthur Nikisch Robert Fuchs Sigismond Bachrich Jules Massenet Margaret Ruthven Lang Frederick Field Bullard George Elbridge Whiting Horatio Parker Ernest Bloch Raissa Myshetskaya Paul Vidal Gabriel Fauré André Gédalge Arnold Schoenberg Théodore Dubois Béla Bartók Vincent -

Chopin's Nocturne Op. 27, No. 2 As a Contribution to the Violist's

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2014 A tale of lovers : Chopin's Nocturne Op. 27, No. 2 as a contribution to the violist's repertory Rafal Zyskowski Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Zyskowski, Rafal, "A tale of lovers : Chopin's Nocturne Op. 27, No. 2 as a contribution to the violist's repertory" (2014). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3366. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3366 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. A TALE OF LOVERS: CHOPIN’S NOCTURNE OP. 27, NO. 2 AS A CONTRIBUTION TO THE VIOLIST’S REPERTORY A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Rafal Zyskowski B.M., Louisiana State University, 2008 M.M., Indiana University, 2010 May 2014 ©2014 Rafal Zyskowski All rights reserved ii Dedicated to Ms. Dorothy Harman, my best friend ever iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS As always in life, the final outcome of our work results from a contribution that was made in one way or another by a great number of people. Thus, I want to express my gratitude to at least some of them. -

Adapting Piano Music for Ballet: Tchaikovsky's Children's Album, Op

Adapting Piano Music for Ballet: Tchaikovsky's Children's Album, Op. 39 Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Stavrianou, Eleni Persefoni Citation Stavrianou, Eleni Persefoni. (2021). Adapting Piano Music for Ballet: Tchaikovsky's Children's Album, Op. 39 (Doctoral dissertation, University of Arizona, Tucson, USA). Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction, presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 06/10/2021 04:39:03 Item License http://rightsstatements.org/vocab/InC/1.0/ Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/660266 ADAPTING PIANO MUSIC FOR BALLET: TCHAIKOVSKY’S CHILDREN’S ALBUM, OP. 39 by Eleni Persefoni Stavrianou ____________________________________ Copyright © Eleni Persefoni Stavrianou 2021 A DMA Critical Essay Submitted to the Faculty of the FRED FOX SCHOOL OF MUSIC In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2021 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Doctor of Musical Arts Creative Project and Lecture-Recital Committee, we certify that we have read the Critical Essay prepared by: titled: and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the Critical Essay requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts. _________________________________________________________________ Date: ____________ _________________________________________________________________ Date: ____________ _________________________________________________________________ Date: ____________ submission of the final copies of the essay to the Graduate College. I hereby certify that I have read this Critical Essay prepared under my direction and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the Critical Essay requirement. -

Alexander Glazunov

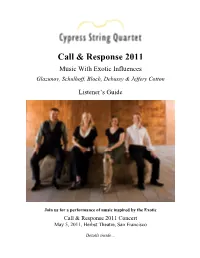

Call & Response 2011 Music With Exotic Influences Glazunov, Schulhoff, Bloch, Debussy & Jeffery Cotton Listener’s Guide Join us for a performance of music inspired by the Exotic Call & Response 2011 Concert May 5, 2011, Herbst Theatre, San Francisco Details inside… Call & Response 2011: Music with exotic influences Concert Thursday, May 5, 2011 Herbst Theatre at the San Francisco War Memorial 401 Van Ness Avenue at McAllister Street San Francisco, CA 7:15pm Pre-Performance Lecture by composer Jeffery Cotton 8:00pm Performance Buy tickets online at: www.cityboxoffice .com or by calling City Box Office: 415-392-4400 Page Contents 3 The Concept: evolution of music over time and across cultures 4 Jeffery Cotton 6 Alexander Glazunov 8 Erwin Schulhoff 10 Ernest Bloch 12 Claude Debussy 2 Call & Response: The Concept Have you ever wondered how composers, modern composers at that, come up with their ideas? How do composers and other artists create new work? Our Call & Response program was born out of the Cypress String Quartet’s commitment to sharing with you and your community this process in music and all kinds of other artwork. We present newly created music based on earlier composed pieces. Why “Call & Response”? We usually associate the term “call & response” with jazz and gospel music, the idea being that the musician plays a musical “call” to which another musician “responds,”—a way of creating a new sound relating in some way to the original. In this program, the “call” is that of Cypress String Quartet searching for connections across musical, historical, and social boundaries. -

Rachmaninoff and Tchaikovsky

APRIL 2020 RACHMANINOFF AND TCHAIKOVSKY APRIL 17 – 19, 2020 MASTERWORKS #7: Two Russian composers, teacher and pupil, both legends in the world of classical music and revered by their countrymen, shared something else in common: periods of severe and crippling depression. Dr. Richard Kogan, a Juilliard-trained pianist, lonely 14-year old into despair.x He mourned the loss graduate of Harvard College and Medical School, of his mother for the rest of his life and called it the and a Clinical Professor of Psychology on the faculty most “crucial event” he’d ever experienced.xi With of the Weill Cornell Medical Center in New York City, his mother’s death, a young Tchaikovsky became has concluded that a disproportionate number of the parent figure for his younger twin brothers, the great composers of classical music suffered from Anatoly and Modest.xii Despite the family’s wish that mental illness.i In his years as a student, Dr. Kogan Tchaikovsky have a career in the Ministry of Justice, pursued both music and pre-medical studies. His the young man was drawn to music. When the St. roommate at Harvard was famed cellist Yo-Yo Ma, Petersburg Conservatory opened its doors in 1862, and, with violinist Lynn Chang, they performed as a Tchaikovsky was among its first students.xiii From that trio.ii With a choice between music and medicine, point forward, his musical path was clear, and his Dr. Kogan chose medicine, but, in so doing, noted work as a composer earned him a teaching position the close relationship between the two fields.iii In at the Moscow Conservatory. -

Concert Program

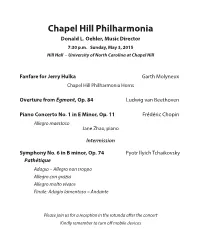

Chapel Hill Philharmonia Donald L. Oehler, Music Director 7:30 p.m. Sunday, May 3, 2015 Hill Hall – University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Fanfare for Jerry Hulka Garth Molyneux Chapel Hill Philharmonia Horns Overture from Egmont, Op. 84 Ludwig van Beethoven Piano Concerto No. 1 in E Minor, Op. 11 Frédéric Chopin Allegro maestoso Jane Zhao, piano Intermission Symphony No. 6 in B minor, Op. 74 Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky Pathétique Adagio – Allegro non troppo Allegro con grazia Allegro molto vivace Finale: Adagio lamentoso – Andante Please join us for a reception in the rotunda after the concert Kindly remember to turn off mobile devices Pathétique The Romantic era idealized heroes. The works on tonight’s Chapel Hill Philharmonia program comprise three dis- tinct takes on heroism—the martyrdom of a leader to the cause of freedom, the creativity of an artist in the face of an incurable illness, and the passionate suffering of an individual descending into silence. Fanfare for Jerry Hulka Jaroslav Hulka, M.D., passed away on November 24, 2014, at age 84. A founding member of the CHP and long time principal French horn player, Jerry also served the orchestra as a board member and president. He is survived by his wife Barbara Sorenson Hulka, a UNC-Chapel Hill professor emerita and former CHP concertmaster. The couple met as undergraduates when both were section princi- pals in the Harvard/Radcliffe Orchestra. The Hulkas have donated generously to the CHP and to classical music programs at UNC- Chapel Hill and throughout the Triangle. In his “day job” Jerry was a well-respected academic and obstetrics/gynecology specialist, recognized as a wise physician, mentor, and innovator. -

The Inextricable Link Between Literature and Music in 19Th

COMPOSERS AS STORYTELLERS: THE INEXTRICABLE LINK BETWEEN LITERATURE AND MUSIC IN 19TH CENTURY RUSSIA A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty of The University of Akron In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Music Ashley Shank December 2010 COMPOSERS AS STORYTELLERS: THE INEXTRICABLE LINK BETWEEN LITERATURE AND MUSIC IN 19TH CENTURY RUSSIA Ashley Shank Thesis Approved: Accepted: _______________________________ _______________________________ Advisor Interim Dean of the College Dr. Brooks Toliver Dr. Dudley Turner _______________________________ _______________________________ Faculty Reader Dean of the Graduate School Mr. George Pope Dr. George R. Newkome _______________________________ _______________________________ School Director Date Dr. William Guegold ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page CHAPTER I. OVERVIEW OF THE DEVELOPMENT OF SECULAR ART MUSIC IN RUSSIA……..………………………………………………..……………….1 Introduction……………………..…………………………………………………1 The Introduction of Secular High Art………………………………………..……3 Nicholas I and the Rise of the Noble Dilettantes…………………..………….....10 The Rise of the Russian School and Musical Professionalism……..……………19 Nationalism…………………………..………………………………………..…23 Arts Policies and Censorship………………………..…………………………...25 II. MUSIC AND LITERATURE AS A CULTURAL DUET………………..…32 Cross-Pollination……………………………………………………………...…32 The Russian Soul in Literature and Music………………..……………………...38 Music in Poetry: Sound and Form…………………………..……………...……44 III. STORIES IN MUSIC…………………………………………………… ….51 iii Opera……………………………………………………………………………..57 -

Chicago Symphony Orchestra Riccardo Muti Zell Music Director

PROGRAM ONE HUNDRED TWENTY-FOURTH SEASON Chicago Symphony Orchestra Riccardo Muti Zell Music Director Pierre Boulez Helen Regenstein Conductor Emeritus Yo-Yo Ma Judson and Joyce Green Creative Consultant Global Sponsor of the CSO Thursday, October 2, 2014, at 8:00 Friday, October 3, 2014, at 1:30 Saturday, October 4, 2014, at 8:30 Riccardo Muti Conductor Christopher Martin Trumpet Panufnik Concerto in modo antico (In one movement) CHRISTOPHER MARTIN First Chicago Symphony Orchestra performances Performed in honor of the centennial of Panufnik’s birth Stravinsky Suite from The Firebird Introduction and Dance of the Firebird Dance of the Princesses Infernal Dance of King Kashchei Berceuse— Finale INTERMISSION Tchaikovsky Symphony No. 3 in D Major, Op. 29 (Polish) Introduction and Allegro—Moderato assai (Tempo marcia funebre) Alla tedesca: Allegro moderato e semplice Andante elegiaco Scherzo: Allegro vivo Finale: Allegro con fuoco (Tempo di polacca) The performance of Panufnik’s Concerto in modo antico is generously supported by the Adam Mickiewicz Institute as part of the Polska Music program. This program is partially supported by grants from the Illinois Arts Council, a state agency, and the National Endowment for the Arts. COMMENTS by Phillip Huscher Andrzej Panufnik Born September 24, 1914, Warsaw, Poland. Died October 27, 1991, London, England. Concerto in modo antico This music grew out of opus 1.” After graduation from the conserva- Andrzej Panufnik’s tory in 1936, Panufnik continued his studies in response to the rebirth of Vienna—he was eager to hear the works of the Warsaw, his birthplace, Second Viennese School there, but found to his which had been devas- dismay that not one work by Schoenberg, Berg, tated during the uprising or Webern was played during his first year in at the end of the Second the city—and then in Paris and London. -

Whose Chopin? Politics and Patriotism in a Song to Remember (1945)

Whose Chopin? Politics and Patriotism in A Song to Remember (1945) John C. Tibbetts Columbia Pictures launched with characteristic puffery its early 1945 release, A Song to Remember, a dramatized biography of nineteenth-century composer Frederic Chopin. "A Song to Remember is destined to rank with the greatest attractions since motion pictures began," boasted a publicity statement, "—seven years of never-ending effort to bring you a glorious new landmark in motion picture achievement."1 Variety subsequently enthused, "This dramatization of the life and times of Frederic Chopin, the Polish musician-patriot, is the most exciting presentation of an artist yet achieved on the screen."2 These accolades proved to be misleading, however. Viewers expecting a "life" of Chopin encountered a very different kind of film. Instead of an historical chronicle of Chopin's life, times, and music, A Song to Remember, to the dismay of several critics, reconstituted the story as a wartime resistance drama targeted more to World War II popular audiences at home and abroad than to enthusiasts of nineteenth-century music history.3 As such, the film belongs to a group of Hollywood wartime propaganda pictures mandated in 1942-1945 by the Office of War Information (OWI) and its Bureau of Motion Pictures (BMP)—and subject, like all films of the time, to the censorial constraints of the Production Code Administration (PCA)—to stress ideology and affirmation in the cause of democracy and to depict the global conflict as a "people's war." No longer was it satisfactory for Hollywood to interpret the war on the rudimentary level of a 0026-3079/2005/4601-115$2.50/0 American Studies, 46:1 (Spring 2005): 115-142 115 116 JohnC.Tibbetts Figure 1: Merle Oberon's "George Sand" made love to Cornel Wilde's "Frederic Chopin" in the 1945 Columbia release, A Song to Remember(couvtQsy Photofest). -

Teacher Notes on Russian Music and Composers Prokofiev Gave up His Popularity and Wrote Music to Please Stalin. He Wrote Music

Teacher Notes on Russian Music and Composers x Prokofiev gave up his popularity and wrote music to please Stalin. He wrote music to please the government. x Stravinsky is known as the great inventor of Russian music. x The 19th century was a time of great musical achievement in Russia. This was the time period in which “The Five” became known. They were: Rimsky-Korsakov (most influential, 1844-1908) Borodin Mussorgsky Cui Balakirev x Tchaikovsky (1840-’93) was not know as one of “The Five”. x Near the end of the Stalinist Period Prokofiev and Shostakovich produced music so peasants could listen to it as they worked. x During the 17th century, Russian music consisted of sacred vocal music or folk type songs. x Peter the Great liked military music (such as the drums). He liked trumpet music, church bells and simple Polish music. He did not like French or Italian music. Nor did Peter the Great like opera. Notes Compiled by Carol Mohrlock 90 Igor Fyodorovich Stravinsky (1882-1971) I gor Stravinsky was born on June 17, 1882, in Oranienbaum, near St. Petersburg, Russia, he died on April 6, 1971, in New York City H e was Russian-born composer particularly renowned for such ballet scores as The Firebird (performed 1910), Petrushka (1911), The Rite of Spring (1913), and Orpheus (1947). The Russian period S travinsky's father, Fyodor Ignatyevich Stravinsky, was a bass singer of great distinction, who had made a successful operatic career for himself, first at Kiev and later in St. Petersburg. Igor was the third of a family of four boys.