Marsha Miro Transcript Final

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Recent Paintings: 1975-1978 Helen Frankenthaler

Recent Paintings: 1975-1978 Helen Frankenthaler cover: Santa Rosa, 1976 Helen Frankenthaler acrylic on canvas 8'9" x 6'2" (266 x 184 cm) collection: Mr. and Mrs. F. R. Weisman Recent Paintings: 1975-1978 Suzanne Lemberg U sdan Gallery Bennington College Bennington, Vermont 15 April - 13 May, 1978 Lenders to the Exhibition: Bennington College takes ever-increasing pleasure and pride in the achievements of one of Mr. and Mrs. Christopher Brumder its most accomplished alumni, Helen Franken- Mr. and Mrs. Thomas J. Davis, Jr. thaler. She has, in the course of her career, Mr. and Mrs. Alan Freedman never failed to credit the College with a role in Mr. Guido Goldman the nurturing of her extraordinary talent. We Mr. and Mrs. David Hermelin are grateful for the love she has for Bennington Mrs. Herbert C. Lee Mr. Jack Lindner and her steadfast support of it. Mr. and Mrs. Ronald Perelman It is fitting, therefore, that her art be herald- Mr. H. B. Sarbin ed in the Usdan Gallery. To do so has required Mr. and Mrs. F. R. Weisman the generosity of those prudent and perspi- Mr. Robert Weiss cacious patrons of the arts who have lent us Mr. Hanford Yang their Frankenthalers: we are grateful to them. Another stalwart friend of the College is the keystone in the organization of this fine exhibi- exhibition directed by tion. Former faculty member Eugene Goossen- E. C . Goossen a long-time devotee of Bennington and Franken- thaler-selected the paintings exhibited, and catalogue design: Alex Brown printed by Queen City Printers Inc. -

Willem De Kooning Biography

G A G O S I A N Willem de Kooning Biography Born in 1904, Rotterdam, Netherlands. Died in 1997, East Hampton, New York, NY. Solo Exhibitions: 2017 Willem de Kooning: Late Paintings. Skarstedt Gallery, London, England. 2016 Willem de Kooning: Drawn and Painted. Princeton University Art Museum, Princeton, NJ. 2015 de Kooning Sculptures, 1972-1974. Skarstedt Gallery, New York, NY. 2014 Willem de Kooning from the John and Kimiko Powers Collection. Bridgestone Museum of Art, Ishibashi Foundation, Tokyo, Japan. 2013 Willem de Kooning: Ten Paintings, 1983–1985. Gagosian Gallery in collaboration with the Willem de Kooning Foundation, 980 Madison Avenue, New York, NY. 2011 de Kooning: A Retrospective. Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY. Willem de Kooning, The Figure: Movement and Gesture. Pace Gallery, New York, NY. 2010 Willem de Kooning: Figure & Light. L&M Arts, Los Angeles, CA. Bon a Tirer: A Lithographic Process. Warner Gallery, Millbrook School, Millbrook, NY. 2008 Willem de Kooning: Werke auf Papier. Galerie Fred John, Munich, Germany. Willem de Kooning: Works on Paper. Xavier Hufkens, Brussels, Belgium. 2007 Willem de Kooning: Drawings: 1920s – 1970s. Allan Stone Gallery, New York, NY. Willem de Kooning: The Last Beginning. Gagosian Gallery, West 21st Street, New York, NY. Willem de Kooning, 1981-1986. L&M Arts, New York, NY. Willem de Kooning: Works on Paper, 1940-1970. Mark Borghi Fine Art Inc., Bridgehampton, NY. Willem de Kooning,: Women. Craig F. Starr Gallery, New York, NY. 2006 Willem de Kooning: The Late Paintings. Organized by Hermitage Projects; The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia; Museo Carlo Bilotti, Rome, Italy. -

Contemporary American Painting and Sculpture

ILLINOIS LIBRARY AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN ARCHITECTURE MUSk^ UBWRY /W»CMITK1t«t mvimu OF aiwos NOTICE: Return or renew all Library Matarialtl The Minimum F*« tor each Loat Book it $50.00. The person charging this material is responsible for its return to the library from which it was withdrawn on or before the Latest Date stamped below. Theft, mutilation, and underlining of books are reasons for discipli* nary action and may result in dismissal from the University. To renew call Telephone Center, 333-6400 UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS LIBRARY AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN L161—O-1096 IKilir^ >UIBRICiil^ I^Aievri^^' cnsify n^ liliiMttiK, llrSMiiRj tiHil \' $4.50 Catalogue and cover design: RAYMOND PERLMAN / W^'^H UtSifv,t- >*r..v,~— •... 3 f ^-^ ':' :iiNTi:A\roiriiitY iiAii<:irii:AN I'iiiKTiNrp A\n kciilp i iikb I!k>7 UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS MAR G 1967 LIBRARY University of Illinois Press, Urbana, Chicago, and London, 1967 IIINTILUIMHtAirY ilAllilltlCAK I'AINTIKi; AKII KCIILI* I llltK l!H»7 Introduction by Allen S. Weller ex/ubition nth College of Fine and Applied Arts, University of Illinois, Urbana «:«Nli:A\l>«ltilKY AAIKIMCAN PAINTINIp A\» StAlLVTUKK DAVID DODDS HENRY President of the University ALLEN S. WELLER Dean, College of Fine and Applied Arts Director, Krannert Art Museum Ctiairmon, Festivol of Contemporory Arts JURY OF SELECTION Allen S. Weller, Choirman James D. Hogan James R. Shipley MUSEUM STAFF Allen S. Weller, Director Muriel B. Ctiristison, Associate Director Deborah A. Jones, Assistant Curator James O. Sowers, Preporotor Jane Powell, Secretary Frieda V. Frillmon, Secretary H. Dixon Bennett, Assistant K. E. -

Michele Oka Doner

MICHELE OKA DONER 1945 — Born in Miami Beach, Florida The artist lives and works in New York, New York. Education 1969 — Post-graduate work at Wayne State University, Detroit, Michigan 1968 — Master of Fine Arts, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan Teaching Fellowship, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan 1966 — Bachelor of Science & Design, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan Solo Exhibitions 2019 — Dust Thou Art, Grounds for Sculpture, Hamilton, New Jersey Mysterium, University of Michigan Museum of Art, Ann Arbor, Michigan 2018 — Lexeme, Wasserman Projects, Detroit, Michigan Bringing The Fire, David Gill Gallery, London, UNITED KINGDOM 2017 — Into the Mysterium, Lowe Art Museum, Miami, Florida 2016 — How I Caught A Swallow in Mid-Air, Perez Art Museum Miami, Miami, Florida Michele Oka Doner at David Gill Gallery, PAD, London, United Kingdom 2015 — Feasting on Bark, Marlborough Gallery, New York, New York Mysterium, David Gill Gallery, London, United Kingdom United States Embassy, Singapore 2014 — The Shaman’s Hut, Christies’, New York, New York 2012 — Michele Oka Doner: Earth Fire Air Water, Art Association of Jackson Hole, Jackson Hole, Wyoming 2011-2012 — Michele Oka Doner: Exhaling Gnosis, Miami Print Shop, Miami, Florida (through 2012) 2011 — Michele Oka Doner: Neuration of the Genus, Dieu Donne, New York, New York 2010 — Spirit and Form: Michele Oka Doner and the Natural World, Frederik Meijer Gardens and Sculpture Park, Grand Rapids, Michigan Down to Earth, Nymphenburg Palace, Munich, Germany 2008-2009 -

Jean-Noel Archive.Qxp.Qxp

THE JEAN-NOËL HERLIN ARCHIVE PROJECT Jean-Noël Herlin New York City 2005 Table of Contents Introduction i Individual artists and performers, collaborators, and groups 1 Individual artists and performers, collaborators, and groups. Selections A-D 77 Group events and clippings by title 109 Group events without title / Organizations 129 Periodicals 149 Introduction In the context of my activity as an antiquarian bookseller I began in 1973 to acquire exhibition invitations/announcements and poster/mailers on painting, sculpture, drawing and prints, performance, and video. I was motivated by the quasi-neglect in which these ephemeral primary sources in art history were held by American commercial channels, and the project to create a database towards the bibliographic recording of largely ignored material. Documentary value and thinness were my only criteria of inclusion. Sources of material were random. Material was acquired as funds could be diverted from my bookshop. With the rapid increase in number and diversity of sources, my initial concept evolved from a documentary to a study archive project on international visual and performing arts, reflecting the appearance of new media and art making/producing practices, globalization, the blurring of lines between high and low, and the challenges to originality and quality as authoritative criteria of classification and appreciation. In addition to painting, sculpture, drawing and prints, performance and video, the Jean-Noël Herlin Archive Project includes material on architecture, design, caricature, comics, animation, mail art, music, dance, theater, photography, film, textiles and the arts of fire. It also contains material on galleries, collectors, museums, foundations, alternative spaces, and clubs. -

BRENDA GOODMAN Born 1943 in Detroit, MI Lives and Works in Pine Hills, NY

BRENDA GOODMAN Born 1943 in Detroit, MI Lives and works in Pine Hills, NY EDUCATION 1961-65 BFA, College for Creative Studies, Detroit, MI SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2019 In a Lighter Place, Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York, NY, January 24 – February 23, 2019 2017 In a New Space, DAVID&SCHWEITZER Contemporary, Brooklyn, NY, September 8 – October 1, 2017 NADA, NY, Jeff Bailey Gallery, Hudson, NY, March 2 – 5, 2017 2016 Jeff Bailey Gallery, Hudson, NY, October 29 – December 18, 2016 2015 Brenda Goodman: Selected Work, 1961-2015, Center Galleries, College for Creative Studies, Detroit, MI, November 14 – December 19, 2018 A Life on Paper, Paul Kotula Projects, Ferndale, MI Brenda Goodman, Life on Mars Gallery, Brooklyn, NY, March 20 – April 19, 2015 2014 John Davis Gallery, Hudson, NY 2012 John Davis Gallery, Hudson, NY 2010 John Davis Gallery, Hudson, NY, July 22 – August 16, 2010 2008 John Davis Gallery, Hudson, NY Paul Kotula Projects, Ferndale, MI 2007 Mabel Smith Douglass Library and Mason Gross School of the Arts Galleries Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ 2003 Littlejohn Contemporary, New York, NY Revolution, Ferndale, MI 2001 Howard Scott Gallery, New York, NY 2000 Nielsen Gallery, Boston, MA Revolution, Ferndale, MI 1999 Kouros Gallery, New York, NY 1998 Revolution, Ferndale, MI 1997 Robert Steele Gallery, New York, NY 1995 Revolution, Ferndale, MI 1994 Cavin-Morris Gallery, New York, NY David Klein Gallery, Birmingham, MI 1993 55 Mercer Street Artists, Inc., New York, NY 1989 Howard Yezerski Gallery, Boston, MA 1988 Hill Gallery, Birmingham, -

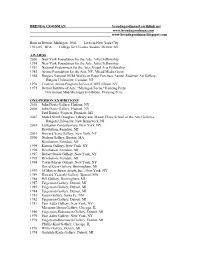

BRENDA GOODMAN [email protected] ______

BRENDA GOODMAN [email protected] www.brendagoodman.com _____________________________________________ www.brendagoodman.blogspot.com Born in Detroit, Michigan 1943 Lives in New York City 1961-65 BFA College for Creative Studies, Detroit, MI AWARDS 2006 New York Foundation for the Arts, Artist Fellowship 1994 New York Foundation for the Arts, Artist Fellowship 1991 National Endowment for the Arts, Visual Arts Fellowship 1985 Ariana Foundation for the Arts, NY, Mixed Media Grant 1984 Rutgers National 83/84 Works on Paper Purchase Award, Stedman Art Gallery, Rutgers University, Camden, NJ 1978 Creative Artists Program Service (CAPS) Grant, NY 1975 Detroit Institute of Arts, "Michigan Focus," Painting Prize 15th Annual Mid-Michigan Exhibition, Drawing Prize ONE-PERSON EXHIBITIONS 2010 John Davis Gallery, Hudson. NY 2008 John Davis Gallery, Hudson, NY Paul Kotula Projects, Ferndale, MI 2007 Mabel Smith Douglass Library and Mason Gross School of the Arts Galleries Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ 2003 Littlejohn Contemporary, New York, NY Revolution, Ferndale, MI 2001 Howard Scott Gallery, New York, NY 2000 Nielsen Gallery, Boston, MA Revolution, Ferndale, MI 1999 Kouros Gallery, New York, NY 1998 Revolution, Ferndale, MI 1997 Robert Steele Gallery, New York, NY 1995 Revolution, Ferndale, MI 1994 Cavin-Morris Gallery, New York, NY David Klein Gallery, Birmingham, MI 1993 55 Mercer Street Artists, Inc., New York, NY 1989 Howard Yezerski Gallery, Boston, MA 1988 Hill Gallery, Birmingham, MI 1987 Feigenson Gallery, Detroit, MI 1985 -

Willem De Kooning

WILLEM DE KOONING Born 1904 Rotterdam, Netherlands Died 1997 East Hampton, New York SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2017 Willem de Kooning - Zao Wou Ki, Lévy Gorvy, New York 2015 de Kooning Sculptures, 1972- 1974, Skarstedt Gallery, New York 2014 Willem de Kooning from the John and Kimiko Powers Collection, Bridgestone Museum of Art, Ishibashi Foundation, Toyko 2013 Ten Paintings, 1983 -1984, Gagosian Gallery in collaboration with The Willem de Kooning Foundation, New York 2011 de Kooning: A Retrospective, Museum of Modern Art, New York Willem de Kooning, The Figure: Movement and Gesture, The Pace Gallery, New York 2010 Willem de Kooning: Figure & Light, L & M Arts, Los Angeles 2008 Willem de Kooning, Works on Paper, Xavier Hufkens, Brussels, Belgium Willem de Kooning: Drawings: 1920s—1970s, Allan Stone Gallery, New York 2007 Williem de Kooning: Women, Craig F. Starr Gallery, New York 2006 Willem de Kooning: Sketchbook, Matthew Marks Gallery, New York Willem de Kooning: Paintings 1975-1978, L&M Arts, New York Willem de Kooning, The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia 2005 Willem de Kooning Retrospective, Kunstforum Vienna, Vienna 2004 A Centennial Exhibition, Gagosian Gallery, New York 2002 Paintings 1967-1984, John Berggruen Gallery, San Francisco Willem de Kooning: Tracing the Figure, The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles Willem de Kooning: Works on Paper & Selected Paintings, Paul Tiebaud Gallery, San Francisco 2000 Willem de Kooning: Mostly Women, Gagosian Gallery, New York 1994 Willem de Kooning: Paintings, National Gallery -

CV Michele Oka Doner-MOD Site December 13, 2018

Michele Oka Doner CV SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2021 Fire, Grounds for Sculpture, Hamilton, New Jersey 2020 The Missing Element, Manitoga. Russel Wright Design Center, Garrison, NY 2018 Stringing Sand on Thread Adler Beatty Gallery Fluent in the Language of Dreams, Wasserman Projects, Detroit, Michigan (Catalog) Strategic Misbehavior, Tower 49, New York, New York (Catalog) Bringing The Fire, David Gill Gallery, London, UK 2017 Into The Mysterium, Lowe Art Museum, University of Miami, Miami, Florida (cat.)(video) Surf Club, Historic Photo Exhibition, curator, Surfside, Florida 2016 How I Caught A Swallow in Mid-Air, Perez Art Museum Miami, Florida (catalog) Michele Oka Doner at David Gill Gallery, PAD, London 2015 Mysterium, David Gill Gallery, London, UK Feasting On Bark, Marlborough Gallery, New York, New York (catalog) 2014 The Shaman’s Hut, Christies, New York, New York (catalog) 2012 Earth, Air, Fire, Water. Art Association of Jackson Hole, Jackson Hole, Wyoming 2011 Michele Oka Doner: Exhaling Gnosis, Miami Biennale, Miami, Florida (catalog) Neuration of the Genus, Dieu Donné Gallery, New York, New York (catalog) 2010 Down to Earth, Nymphenburg Palace, Munich, Germany online catalog: http://www.nymphenburg.com/en/products/editions/down-to-earth Spirit and Form: Michele Oka Doner and the Natural World, Frederik Meijer Gardens & Sculpture Park, Grand Rapids, Michigan (catalog) 2008 HumanNature (Bronze, Clay, Porcelain, Works on Paper), Marlborough Gallery (Chelsea), New York, New York (catalog) 2004 Four Decades, Four Media, Marlborough Gallery, New York, New York 2003 Michele Oka Doner: New Sculpture, Marlborough Gallery (Chelsea), New York, New York (catalog) Fleeting Moments, MIA Gallery, Miami, Florida (catalog) Palmacae, Christofle, Paris, France 2001 ELP Studio, Rome, Italy 2000 Paper/Papers, Willoughby Sharp Gallery, New York, New York A Fuoco, Studio Stefania Miscetti, Rome, Italy 1998 Ceremonial Silver, Primavera Gallery, New York, New York (catalog) 1991 Michele Oka Doner Sculpture. -

Cass Corridor Documentation Project

COLBY INTERVIEW 1 Cass Corridor Documentation Project Oral History Project Interviewee: Joy Hakanson Colby Relationship to Cass Corridor: Art Critic for Detroit News, 1947-2006 Interviewer: Jennifer Dye Date of Interview: November 22, 2011 Location: Telephone interview from Kresge Library, Wayne State University and St. Louis Dye: This is Jennifer Dye, and I’m interviewing Joy Hakanson Colby for the Cass Corridor Art Project. I am in Detroit, and it is November 22nd, 2011, and Joy is in St. Louis. And you know that I’m recording this? Colby: Yes Dye: OK. I’m going to ask some questions, some of which I’ve already asked before in our conversations. Where were you born? Colby: I was born in Detroit. Dye: And did you grow up in Detroit? COLBY INTERVIEW 2 Colby: I grew up in Detroit and graduated from Wayne State. Dye: Can you tell me something about your parents? Colby: I was an adopted child, and my father’s family was born in Sweden and came over in New York. My mother’s family belonged to the Detroit German community. And they were wonderful people. I mean amazing people. I have never looked for birth parents, because that seemed kind of a slap in their face. Dye: Did you have any siblings? Colby: No, no siblings. Dye: You were an only child. When was the first time you remember being interested in art? Colby: Well, my parents took me to the Detroit Institute of Arts. I kind of grew up in there. I always had lessons of all sorts. -

A Finding Aid to the Gertrude Kasle Gallery Records, 1949-1999 (Bulk 1964-1983), in the Archives of American Art

A Finding Aid to the Gertrude Kasle Gallery Records, 1949-1999 (bulk 1964-1983), in the Archives of American Art Kim L. Dixon November 01, 2007 Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Historical Note.................................................................................................................. 2 Scope and Content Note................................................................................................. 3 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 3 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 4 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 5 Series 1: Artist Files, 1949-1999.............................................................................. 5 Series 2: Gallery and Personal Business and Administrative Files, 1961-1995..... 13 Series 3: Exhibition Files, 1963-1976.................................................................... 16 Series 4: Photographic Material, 1953-1985......................................................... -

JACK TWORKOV Born 1900, Biala, Poland Died 1982, Provincetown, MA

JACK TWORKOV Born 1900, Biala, Poland Died 1982, Provincetown, MA ONE-PERSON EXHIBITIONS 1939 "Jack Tworkov: Paintings," ACA Gallery, New York, NY, December 31, 1939-January 13, 1940 (check list). 1947 “Tworkov: Still-Life Series,” Charles Egan Gallery, New York, NY, October 25-November 15. 1948 “Jack Tworkov,” The Watkins Gallery, The American University Campus, July. “Paintings by Jack Tworkov,” Baltimore Museum, Baltimore, MD, October 22-November 30. 1949 “Tworkov: New Paintings,” Charles Egan Gallery, New York, NY, October 17-November 5. 1950 “Jack Tworkov,” Whyte Bookshop & Gallery, Washington, DC, January. 1952 “Jack Tworkov,” Charles Egan Gallery, New York, NY, March 3-March 31. 1954 “Jack Tworkov: Paintings and Drawings, 1951-1954,” Charles Egan Gallery, New York, NY, March16-April 10. "Jack Tworkov," University of Mississippi, Oxford, MS, October 10-November. 1957 “Drawings by Jack Tworkov,” The Jefferson Place Gallery, Washington, DC, March 26-April 18. “Tworkov: Exhibition of Paintings,” Stable Gallery, New York, NY, April 15-May 4 (catalogue). “Paintings by Jack Tworkov,” Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, MN, December 1-December 29 (catalogue). 1958 “Tworkov: Exhibition of Drawings, 1954-58,” Stable Gallery, New York, NY, November–December. 1959 "Tworkov," Stable Gallery, New York, NY, April 6–April 25 (check list). 1960 “Tworkov, 1950/60.” Holland-Goldowsky Gallery, Chicago, IL, October 8-November 4 (catalogue). 1961 “Jack Tworkov,” Leo Castelli Gallery, New York, NY, February 28-March 18. “Jack Tworkov,” Newcomb College Art Gallery, Tulane University, New Orleans, LA, April 24-April 30. 1963 “Jack Tworkov,” Leo Castelli Gallery, New York, NY, February 9-March 7. “Recent Paintings by Jack Tworkov,” Yale University Art Gallery, Yale University, New Haven, CT, November 9-January 6, 1964 (catalogue).