HOLMES-EDDTREATISE-2012.Pdf (3.937Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Packers Weekly Media Information Packet

PACKERS WEEKLY MEDIA INFORMATION PACKET OAKLAND RAIDERS VS GREEN BAY PACKERS THURSDAY, AUGUST 18, 2016 @ 7 PM CDT • LAMBEAU FIELD Packers Public Relations l Lambeau Field Atrium l 1265 Lombardi Avenue l Green Bay, WI 54304 l 920/569-7500 l 920/569-7201 fax Jason Wahlers, Aaron Popkey, Sarah Quick, Tom Fanning, Nathan LoCascio, Katie Hermsen VOL. XVIII; NO. 5 PRESEASON WEEK 2 GREEN BAY (1-0) VS. OAKLAND (1-0) u Due to the Olympics, this week’s game will air on WMLW-TV in Thursday, Aug. 18 l Lambeau Field l 7 p.m. CDT Milwaukee instead of WTMJ-TV and on WACY-TV in Green Bay instead of WGBA-TV. In addition the game will be televised over WKOW/ABC, PACKERS STAY HOME TO PLAY THE RAIDERS Madison, Wis.; WAOW/ABC, Wausau/Rhinelander, Wis.; WXOW/ABC, The Green Bay Packers will take on the Oakland Raiders this La Crosse, Wis.; WQOW/ABC, Eau Claire, Wis.; WLUC/NBC, Escanaba/ Thursday at Lambeau Field in the Bishop’s Charities Game. Marquette, Mich.; KQDS-TV/FOX, Duluth/Superior, Minn.; WHBF-TV/CBS, uThe Packers and Raiders will face each other for the 10th Davenport, Iowa (Quad Cities); KWWL-TV/NBC, Cedar Rapids/Waterloo, time in the preseason. The Raiders lead the preseason Iowa; KCWI-TV/CW, Des Moines, Iowa; KMTV-TV/CBS, Omaha, Neb.; series, 5-4, while Green Bay leads the regular-season KYUR/ABC, Anchorage, Alaska; KATN/ABC, Fairbanks, Alaska; KJUD/ABC, series, 7-5. uThis will be the third consecutive year the Packers and Raiders play Juneau, Alaska; and KFVE-TV in Honolulu, Hawaii. -

2017 Southern Miss Football Media Guide

Southern Miss 2017 Football Almanac Conference USA Champions n 1996, 1997, 1999, 2003, 2011 2017 Southern Miss Golden Eagles Quick Facts General Table of Contents Best Time/Day to Reach: Through SID School: University of Southern Mississippi Assistant Head Coach/Safeties: Tim Billings 1..................................................Quick Facts Preferred: Southern Miss Alma Mater: Southeastern Oklahoma State, 1980 2-3 ................................... Media Information City: Hattiesburg, Miss. Offensive Coordinator/ 3......................................................... Credits Founded: 1910 Quarterbacks: Shannon Dawson Enrollment: 14,554 Alma Mater: Wingate, 2001 3..................................... Contact Information Nickname: Golden Eagles Defensive Coordinator/ 4.............................................. Media Outlets Colors: Black and Gold Inside Linebackers: Tony Pecoraro 5..............Southern Miss IMG Sports Network Stadium (Capacity): Carlisle-Faulkner Field Alma Mater: Florida State, 2003 5.............................................Radio Affiliates at M.M. Roberts Stadium (36,000) Inside Wide Receivers: Scotty Walden 6-7 ...... 2017 Numerical/Alphabetical Rosters Surface: Matrix Alma Mater: Sul Ross State, 2012 8...................................Post-spring Two-Deep Affiliation: NCAA Division I Cornerbacks: Dan Disch 9.............................. Head Coach Jay Hopson Conference: Conference USA Alma Mater: Florida State, 1981 10-15 .................................Assistant Coaches President: Dr. Rodney Bennett -

The Mottley Crew Review

PRST STD 11/20 US POSTAGE PAID BOISE, ID 1700 Bayberry Court, Suite 203 PERMIT 411 Richmond, Virginia 23226 THE MOTTLEY CREW REVIEW INSIDE THIS ISSUE www.MottleyLawFirm.com | (804) 823-2011 www.MottleyLawFirm.com | (804) 823-2011 1 What Can We Be Thankful for in a Year WHAT CAN WE BE THANKFUL FOR IN A YEAR LIKE THIS? Like This? A LOOK BACK AT THE WACKY RIDE OF 2020 2 Top 5 Healthy Life Hacks to Have an Awesome Morning This November, I decided to take a road trip! back at that perky January article and feel This four-day retreat was a much-needed hopeless about the contrast, but that 3 Memorable Thanksgiving Day Football Plays break from the practice of law. It was filled is not how I see it. with fishing, hunting, and college football. The way I see it, if The icing on the cake was catching up with you could survive 3 Kevin’s Favorite Winter Soups my son at the University of South Carolina. this year, you’re We went to see the Gamecocks take on unstoppable! I’m the Texas A&M Aggies that weekend in a still looking at the stadium that holds over 80,000. That night, world through an it only had about 20,000 fans in attendance. optimistic lens, and The closest fans to us were about 30 feet this holiday season, away. What a change from last year. I think we all have a tremendous This trip was super fun, but I had a lot of amount to be thankful for. -

AN HONOURED PAST... and Bright Future an HONOURED PAST

2012 Induction Saturday, June 16, 2012 Convention Hall, Conexus Arts Centre, 200 Lakeshore Drive, Regina, Saskatchewan AN HONOURED PAST... and bright future AN HONOURED PAST... and bright future 2012 Induction Saturday, June 16, 2012 Convention Hall , Conexus Arts Centre, 200 Lakeshore Drive, Regina, Saskatchewan INDUCTION PROGRAM THE SASKATCHEWAN Master of Ceremonies: SPORTS HALL OF FAME Rod Pedersen 2011-12 Parade of Inductees BOARD OF DIRECTORS President: Hugh Vassos INDUCTION CEREMONY Vice President: Trent Fraser Treasurer: Reid Mossing Fiona Smith-Bell - Hockey Secretary: Scott Waters Don Clark - Wrestling Past President: Paul Spasoff Orland Kurtenbach - Hockey DIRECTORS: Darcey Busse - Volleyball Linda Burnham Judy Peddle - Athletics Steve Chisholm Donna Veale - Softball Jim Dundas Karin Lofstrom - Multi Sport Brooks Findlay Greg Indzeoski Vanessa Monar Enweani - Athletics Shirley Kowalski 2007 Saskatchewan Roughrider Football Team Scott MacQuarrie Michael Mintenko - Swimming Vance McNab Nomination Process Inductee Eligibility is as follows: ATHLETE: * Nominees must have represented sport with distinction in athletic competition; both in Saskatchewan and outside the province; or whose example has brought great credit to the sport and high respect for the individual; and whose conduct will not bring discredit to the SSHF. * Nominees must have compiled an outstanding record in one or more sports. * Nominees must be individuals with substantial connections to Saskatchewan. * Nominees do not have to be first recognized by a local satellite hall of fame, if available. * The Junior level of competition will be the minimum level of accomplishment considered for eligibility. * Regardless of age, if an individual competes in an open competition, a nomination will be considered. * Generally speaking, athletes will not be inducted for at least three (3) years after they have finished competing (retired). -

Thanksgiving History and Records

THANKSGIVING LEADERS PASSING TOUCHDOWNS | THANKSGIVING PLAYERS TONY ROMO 18 WITH THE MOST CAREER PASSING TDs QUARTERBACK | #9 PASSING 2. Matthew Stafford 17 3t. Bobby LayneHOF, Danny White 14 HOF HOF YARDS 5t. Troy Aikman , Brett Favre 11 ON THANKSGIVING PASSER RATING (MIN. 75 ATTEMPTS) | THANKSGIVING TOM BRADY MATTHEW STAFFORD 121.8 2,705 PASSING YARDS PASSER RATING QUARTERBACK | #12 2. Kirk Cousins 110.8 TONY ROMO 3. Brett FavreHOF 110.5 2,338 PASSING YARDS 4. Eric Hipple 103.6 TROY AIKMANHOF RUSHING YARDS | THANKSGIVING 2,174 PASSING YARDS EMMITT SMITHHOF 1,178 RUSHING YARDS DANNY WHITE RUNNING BACK | #22 1,545 PASSING YARDS 2. Barry SandersHOF 931 3. Tony DorsettHOF 723 BART STARRHOF 4. Walter PaytonHOF 493 1,345 PASSING YARDS RUSHING TOUCHDOWNS | THANKSGIVING EMMITT SMITHHOF 13 RUSHING TDs RUNNING BACK | #22 2. Tony DorsettHOF 9 PLAYERS 3. Barry SandersHOF 8 WITH THE MOST CAREER RECEIVING TOUCHDOWNS | THANKSGIVING RECEIVING CALVIN JOHNSON 11 RECEIVING TDs WIDE RECEIVER | #81 YARDS 2. Cloyce Box 7 ON THANKSGIVING 3. Michael IrvinHOF 6 JASON WITTEN 853 RECEIVING YARDS SACKS | THANKSGIVING EZEKIEL ANSAH 8.5 HERMAN MOORE SACKS DEFENSIVE END | #94 834 RECEIVING YARDS 2. Randy WhiteHOF 8.0 3t. Tracy Scroggins, Tony Tolbert 6.0 CALVIN JOHNSON 769 RECEIVING YARDS INTERCEPTIONS | THANKSGIVING BOBBY DILLON 6 MICHAEL IRVINHOF INTs 722 RECEIVING YARDS DEFENSIVE BACK | #44 2t. Jim David, Dick LeBeauHOF 5 HOF TONY HILL 4t. Yale Lary , Terence Newman, Everson Walls 4 622 RECEIVING YARDS THANKSGIVING MEMORABLE MOMENTS Nov. 24, 2016 Nov. 28, 1974 Minnesota Vikings 13 @ Detriot Lions 16 Washington Redskins 23 @ Dallas Cowboys 24 Lions kicker Matt Prater hit two field goals in the Trailing 16-3 in the third quarter, rookie quarterback final two minutes, tying the game and then ending Clint Longley replaced injured Hall of Famer Roger it with no time on the clock, after Darius Slay Staubach and threw a game-winning 50-yard returned an interception to the Vikings’ 20 with 30 touchdown to Drew Pearson with 28 seconds seconds remaining. -

All-Time Cfl All-Stars

ALL-TIME CFL ALL-STARS 2018 2008 2000 Ed Gainey Wes Cates Andrew Greene Charleston Hughes Maurice Lloyd Curtis Marsh Willie Jefferson Gene Makowsky Demetrious Maxie Brendon LaBatte Anton McKenzie George White 2017 2007 1998 Duron Carter Kerry Joseph Don Narcisse Ed Gainey Jeremy O'Day Willie Jefferson 1997 Brendon LaBatte 2006 Bobby Jurasin Eddie Davis 2015 Gene Makowsky 1996 Brendon LaBatte Jeremy O'Day Robert Mimbs Fred Perry 2014 1995 Tyron Brackenridge 2005 Don Narcisse John Chick Eddie Davis Brendon LaBatte Andrew Greene 1994 Corey Holmes Mike Anderson 2013 Gene Makowsky Ron Goetz Tyron Brackenridge Omarr Morgan Weston Dressler Scott Schultz 1993 Alex Hall Jearld Baylis Brendon LaBatte 2004 Ray Elgaard Kory Sheets Eddie Davis Dave Ridgway Nate Davis Glen Suitor 2012 Andrew Greene Barry Wilburn Weston Dressler Gene Makowsky 1992 2011 2003 Jearld Baylis Jerrell Freeman Andrew Greene Ray Elgaard Reggie Hunt Bobby Jurasin 2010 Jackie Mitchell Vic Stevenson Andy Fantuz Omarr Morgan Glen Suitor James Patrick 2002 1991 2009 Derrick Armstrong Glen Suitor John Chick Corey Holmes Gene Makowsky Omarr Morgan 1990 Jeremy O'Day Roger Aldag Kent Austin Don Narcisse Dave Ridgway 1989 1977 1968 Roger Aldag Ralph Galloway Clyde Brock Eddie Lowe Wally Dempsey Tim McCray 1976 Bob Kosid Don Narcisse Rhett Dawson Ed McQuarters Dave Ridgway Ralph Galloway George Reed Roger Goree Ted Urness 1988 Ron Lancaster Roger Aldag Lorne Richardson 1967 Ray Elgaard Paul Williams Jack Abendschan Bobby Jurasin Clyde Brock Dave Ridgway 1975 Garner Ekstran Ron Lancaster -

Preserving the Sports History of Chautauqua County

Honoring and Preserving the Sports History of Chautauqua County 15 West Third Street - Jamestown, NY 14701 January 2016 2016 CSHOF BANQUET SPEAKER Don Beebe Don Beebe, one of the most popular and respected players in Buffalo Bills history, will be the featured speaker at the 35th Annual Induction Banquet of the Chautauqua Sports Hall of Fame on February 15 at the Lakewood Rod & Gun Club. “We are excited to have Don ‘Beebs’ Beebe as the guest speaker for our dinner,” said Randy Anderson, CSHOF president. “Don was known as a player with a strong work ethic and a moral character above reproach. He exemplified putting the success of the team over his own statistics. “Beebe is a role model for what it means to be an athlete, a teammate and a sportsman. He has a strong message that will be an inspiration to our honorees and guests at the banquet. His appearance will add a special touch to the induction of Alex Conti, Julie Gawronski Tickle, Dan Hoard, Sarah Schuster Morrison, Robert “Doc” Rappole, Jim Ulrich, Heather Lefford Edborg, Clarence “Flash” Olson and Parke Hill Davis.” Tickets for the induction dinner are priced at $50 and are available at the Jock Shop in Jamestown, Matt’s News in Dunkirk or by calling Chip Johnson at 716-485-6991. Don Beebe Bio Don “Beebs” Beebe is a former wide receiver who played for the Buffalo Bills (1989– 1994), Carolina Panthers (1995) and Green Bay Packers (1996–1997) of the NFL, and is considered one of the fastest players in NFL history with a recorded a 4.21 40-yard dash time. -

Canton, Ohio and the National Football League

PRO FOOTBALL HALL OF FAME TEACHER ACTIVITY GUIDE 2019-2020 EDITIOn DALLAS COWBOYS Team History In 1960, the Dallas Cowboys became the NFL’s first successful new team since the collapse of the All- America Football Conference 10 years earlier. Clint Murchison Jr. was the new team’s majority owner and his first order of business was to hire Tex Schramm as general manager, Tom Landry as head coach and Gil Brandt as player personnel director. This trio was destined for almost unprecedented success in the pro football world but the “glory years” didn’t come easily. Playing in the storied Cotton Bowl, the 1960 Cowboys had to settle for one tie in 12 games and Dallas didn’t break even until its sixth season in 1965. But in 1966, the Cowboys began an NFL-record streak of 20 consecutive winning seasons. That streak included 18 years in the playoffs, 13 divisional championships, five trips to the Super Bowl and victories in Super Bowls VI and XII. Dallas won its first two divisional championships in 1966 and 1967 but lost to the Green Bay Packers in the NFL championship game each year. Similar playoff losses the next seasons were followed by a 16-13 last-second loss to Baltimore in Super Bowl V following the 1970 season. The Cowboys were typified as “a good team that couldn’t win the big games.” But they dispelled such thought for good the very next year with a 24-3 win over the Miami Dolphins in Super Bowl VI. The Cowboys were Super Bowl-bound three more times from 1975 to 1978. -

Final WAC Football Records

WESTERN ATHLETIC CONFERENCE • WESTERN ATHLETIC CONFERENCE • WESTERN ATHLETIC CONFERENCE • WESTERN ATHLETIC CONFERENCE • WESTERN ATHLETIC CONFERENCE WAC RECORDS–OFFENSE RUSHING SCOring Most Made Passing Most Rushes Most Points Scored Game 30 Brigham Young vs. Colorado State, Game 90 New Mexico vs. UTEP, Nov. 13, 1971 Quarter 36 Brigham Young vs. Washington State, Nov. 7, 1981 Season 782 Air Force, 1987 Nov. 15, 1990 Season 281 Hawai‘i, 2006 Most Yards Gained Half 56 Arizona State vs. New Mexico, Nov. Most Made By Penalty Game 672 Rice vs. Louisiana Tech, Nov. 29, 2003 2, 1968; Game 7 9 times; last Texas State at UTSA, Season 4,635 Air Force, 1987 56 Fresno State vs. Utah State, Dec. 1, Nov. 24, 2012 Average Gain Per Rush 2001 Season 40 Louisiana Tech, 2012 Game 12.7 Hawai‘i vs. New Mexico State, Nov. Game 83 Brigham Young vs. UTEP, Nov. 1, 1980 27, 2010 (291-23) Season 656 Hawai‘i, 2006 Penalties Season 7.39 Nevada, 2009 (607-4484) Largest Winning Margin Most Against Most Touchdowns Scored WAC Game 76 Utah over UTEP, Sept. 22, 1973 (82-6) Game 22 Brigham Young vs. Utah State, Oct. Game 10 Air Force vs. New Mexico, Nov. 14, 76 Brigham Young over UTEP, Nov. 1, 18, 1980; 1987 1980 (83-7) 22 UTEP vs. Brigham Young, Sept. 19, Season 52 Nevada, 2010 Defensive Extra Points 1981 Game 1 Utah vs. Air Force, Nov. 12, 1994; Season 124 Fresno State, 2001 Passing 1 Colorado State vs. UT-Chattanooga, Most Yards Penalized Most Attempts Aug. 31, 1996; Game 217 UTEP vs. -

Divisional All-Stars

ALL-TIME WESTERN ALL-STARS 2018 2011 2006 2001 1993 Ed Gainey Craig Butler Eddie Davis Darren Davis Jearld Baylis Charleston Hughes Weston Dressler Matt Dominguez Eddie Davis Ray Elgaard Willie Jefferson Jerrell Freeman Reggie Hunt Andrew Greene Don Narcisse Brendon LaBatte Kenton Keith Omarr Morgan Dave Ridgway Brett Lauther 2010 Gene Makowsky Shonte Peoples Glen Suitor Wes Cates Jeremy O'Day George White Barry Wilburn 2017 Andy Fantuz Fred Perry Duron Carter Gene Makowsky 2000 1992 Ed Gainey Jeremy O'Day 2005 Andrew Greene Jearld Baylis Willie Jefferson James Patrick Eddie Davis Curtis Marsh Ray Elgaard Brendon LaBatte Barrin Simpson Andrew Greene Demetrious Maxie Bobby Jurasin Naaman Roosevelt Corey Holmes George White Vic Stevenson 2009 Gene Makowsky Glen Suitor 2015 Stevie Baggs Omarr Morgan 1999 Jeff Knox Jr. John Chick Jeremy O'Day Willie Pless 1991 Brendon LaBatte Weston Dressler Scott Schultz Neal Smith Roger Aldag Darian Durant Elijah Thurmon John Terry Gary Lewis 2014 Lance Frazier Dave Ridgway Rob Bagg Tad Kornegay 2004 1998 Vic Stevenson Tyron Brackenridge Sean Lucas Eddie Davis Don Narcisse Glen Suitor John Chick Gene Makowsky Nate Davis John Terry Tearrius George Jeremy O'Day Andrew Greene 1990 Brendon LaBatte Reggie Hunt 1997 Roger Aldag 2008 Kenton Keith Dale Joseph Kent Austin 2013 Wes Cates Gene Makowsky Bobby Jurasin Ray Elgaard Dwight Anderson Maurice Lloyd John Terry Richie Hall Tyron Brackenridge Gene Makowsky 2003 Don Narcisse Weston Dressler Anton McKenzie Nate Davis 1996 Dan Rashovich Darian Durant Andrew Greene -

TROY FOOTBALL REVIEW Join Head Coach Larry Blakeney and Host Barry Mcknight Each Week As They Provide a Breakdown of the Previous Game and Preview Next Week’S Contest

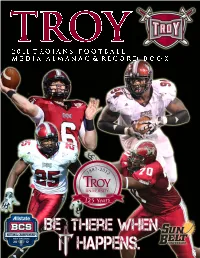

HISTORY HISTORY | TROY UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF ATHLETICS 5000 Veterans Stadium Drive Troy, AL 36082 334.670.3482 www.TroyTrojans.com CREDITS CAREER/SINGLE-SEASON RECORDS EXECUTIVE EDITORS Ricky Hazel, Travis Jarome | EDITORIAL ASSISTANCE Taylor Bryan, Dan Ensey, Ben Maxwell, Matt Mays, Tyler Pigg COMPILATION ON THE COVER: The cover of the 2011 Troy Football Travis Jarome, Ricky Hazel, Taylor Bryan, Dan Ensey, Ben Maxwell, Tyler Pigg, Brynna Waters and the past Media Relations contacts for TROY Almanac includes the Trojans four preseason All-Sun Belt football Conference selections. They are: QB Corey Robinson (top left), DE Jonathan Massaquoi (top right), LB Xavier Lamb (bottom left) and OL James Brown (bottom right). LAYOUT Travis Jarome, Ricky Hazel, Taylor Bryan Copyright, 2011, Troy University Department of Athletics TROY UNIVERSITY MISSION STATEMENT Troy University is a public institution comprised of a network of campuses throughout Alabama and worldwide. International in scope, Troy University provides a variety of educational programs at the undergraduate and graduate levels for a diverse student body in traditional, nontraditional and emerging electronic formats. Academic programs are supported by a variety of student services which promote the welfare of the individual student. Troy University’s dedicated faculty and staff promote discovery and exploration of knowledge and its application to life-long success through effective teaching, service, creative partnerships, scholarship and research. | 2011 OUTLOOK | COACHES AND STAFF | PLAYERS | 2011 OPPONENTS 2010 YEAR IN REVIEW | PLAYERS AND STAFF | COACHES | 2011 OUTLOOK TROY ATHLETICS MISSION STATEMENT The Troy University Athletics Department is an integral part of the Univer- sity. Its mission is to assure a balance between the desire to win and the desire to facilitate positive growth of student-athletes. -

Warhawks Game Ten

ULM aT WarhaWks GaMe Ten 2010 schedULe Date Opponent (BCS/AP/Coaches) Time/Result ULM (4-5, 3-3 sUn BeLT) Sept. 11 ! #14/15 Arkansas (FSN) L, 7-31 Sept. 18 * at Arkansas State (SBN) L, 20-34 aT Sept. 25 Southeastern Louisiana W, 21-20 Oct. 2 at #10/11 Auburn (ESPNU) L, 3-52 Oct. 9 * Florida Atlantic W, 20-17 #5 LsU (8-1, 5-1 sec) Oct. 16 * at Western Kentucky W, 35-30 Oct. 23 * at Middle Tennessee L, 10-38 Oct. 30 * Troy (SBN) W, 28-14 nov. 13, 2010 6 p.M. / TiGervision Nov. 6 * at FIU (SBN) L, 35-42 (2OT) TiGer sTadium (92,400) BaTon rouge, La. Nov. 13 at #5/5/6 LSU (PPV/Tiger Vision) 6 p.m. Nov. 20 * North Texas 2:30 p.m. Nov. 27 * UL-Lafayette 2:30 p.m. d i d yo U k n oW ? Tale of the Tape * Sun Belt Conference Game / ! at Little Rock, Ark. / All times Central • ULM is the last team to beat Alabama in Bryant- Offense ULM LSU Denny Stadium -- a streak of 18 straight wins for Points 179 228 Alabama. The Warhawks defeated the Crimson Average 19.9 25.3 ULM Tide 21-14 on Nov. 17, 2007 First Downs/Game 18.7 16.9 By The nUMBers • ULM has handed Troy its only two Sun Belt Con- Total Offense 3148 2976 ference losses in its last 19 league games Average 349.8 330.7 2 Kolton Browning’s 265.2 yards of total offense Net Rushing 906 1658 per game are the second most by a freshman in the NCAA, • Ten of ULM’s starting 22 on offense and defense Average 100.7 184.2 he trails only Troy’s Corey Robinson (270.5) are freshmen and sophomores.