TRANSPORTATION by Mrs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mechanical Engineering Magazine

BIG INCH PIPELINE LITTLE BIG INCH PIPELINE STORAGE TANKS PUMPING STATIONS PIPELINES Downloaded from http://asmedigitalcollection.asme.org/memagazineselect/article-pdf/138/07/40/6359862/me-2016-jul3.pdf by guest on 28 September 2021 FOR WAR AND PEACE BY FRANK WICKS These 24-inch pipes were stacked and ready to be assembled into the Big Inch Pipeline, in this 1942 image from the U.S. Farm Security Administration. Photographer John Vachon took this photo in Pennsylvania. MECHANICAL ENGINEERING | JULY 2016 | P.41 orld War II was largely about oil, Downloaded from http://asmedigitalcollection.asme.org/memagazineselect/article-pdf/138/07/40/6359862/me-2016-jul3.pdf by guest on 28 September 2021 and fought with oil. The United States factories and work force, largely idled by the lingering Great Depression, would convert Wto the massive production of land vehicles, ships, and aircraft. These war machines were trans- ported to combat zones, but would be worthless without oil. Of the seven billion barrels of oil used by the Allies, 80 percent came from the United States, mostly from Texas and the Gulf Coast. Prior to the war, much of the crude oil and refi ned products had been transported by coastal tank- ers to the northeast and then shipped across the Atlantic. War started raging in Europe in 1939. The United States remained offi cially neutral until the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December They wouldn’t be the country’s fi rst pipelines, The tanker 1941. but they would be the largest. Building them Dixie Arrow was torpedoed off Cape When Hitler declared war on the United States would be the largest joint government and private Hatteras in March a few days later, he gave Germany free rein for industry project to that time. -

Recent Federal Regulation of the Petroleum Pipe Line As a Common Carrier Theodore L

Cornell Law Review Volume 32 Article 2 Issue 3 March 1947 Recent Federal Regulation of the Petroleum Pipe Line as a Common Carrier Theodore L. Whitesel Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/clr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Theodore L. Whitesel, Recent Federal Regulation of the Petroleum Pipe Line as a Common Carrier , 32 Cornell L. Rev. 337 (1947) Available at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/clr/vol32/iss3/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cornell Law Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RECENT FEDERAL REGULATION OF THE PETRO- LEUM PIPE LINE AS A COMMON CARRIER THEODORE L. WHITESEL Jurisdiction Under the Interstate Commerce Act Regulation of the interstate petroleum pipe line as a common carrier under the Interstate Commerce Act has had as its major purpose the achievement of competition among shippers in the petroleum industry It is the object of this survey to examine the recent attempts at regulation to see if this purpose has been achieved' and to set forth the legal and economic factors entering into the problem of regulation. The groups that favor petroleum pipe line regulation to maintain com- petition are the consumers of refined petroleum products, the independent refiners of crude oil, the independent jobbers of refined petroleum products, the independent service station dealers, the competitive carriers of petroleum, lt might well be the objective of a study to appraise the economic merits of com- petitive organization of the oil industry as compared to monopolistic organization under government control,-backgrounded against the national welfare and the national de- fense. -

Interstate Pipelines a Plan for a New New York

LARRY SHARPE FOR NEW YORK Interstate Pipelines A Plan for a New New York Prepared for: Larry Sharpe for NY Governor Prepared by: Russ Clark, Deputy Policy Director, Larry Sharpe for New York May 28, 2018 Proposal number: IF-0002 LARRY SHARPE FOR NEW YORK EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Objective To provide a path forward for natural gas and petroleum pipelines in New York. Goals 1) Reduce the cost of energy in New York. 2) Protect land values and encourage co-location of pipelines with other energy corridors. 3) Provide jobs and economic development while reducing the need to import energy from other states. 4) Prevent shortfalls in electric energy supply for both NYISO and NEISO. Background 1) Upon entering World War II, Nazi submarines sunk petroleum fuel and crude oil barges headed for Philadelphia and New York. According to historian Keith Miller, “They were highly effective and many Caribbean island beaches were seriously polluted with oil,”. In response, the United States government commissioned the construction of two pipelines from Texas to Pennsylvania and New York to support the war effort and provide export terminals to supply European allies with fuel. The pipelines were privatized and converted to natural gas service following the conclusion of the war (“Big Inch Pipelines of WWII”, American Oil and Gas Historical Society). Today, New York imports much of its natural gas supply from other states, including Pennsylvania, Texas and Louisiana, which is supplemented by additional imports from Canada via the Iroquois pipeline. (Energy Information Agency, 2018) 2) Following several pricing and supply crises in the late 1970’s, Congress passed the Natural Gas Policy Act in 1978. -

Pre-Job List

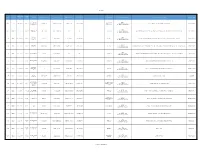

Pre Jobs Total On Pre Approx. Pre Job Start Date Contractor Warehouse Location Steward Welder Foreman Welders Phone Gas Company Hours, Wages, & Per Diem Job Description & Welding Test Business Agent Job End 5x10 1X8 LMC Industrial LMC Industrial 14380 TBD W-1 J-1 H-3 10/29/21 Fort Plain, NY Donaldson, Rodney W Fegley, Eric M (315) 651-5944 W&J-43.18 H-23.30 12" meter station work located in Montgomery County, NY David Butterworth Contractors, Inc. Contractors, Inc. W- 150.50 J- 90.50 H- 64.50 5x10 John E. Green 14359 10/4/21 W-1 J-1 H-2 10/15/21 East China, MI Downer, Stephen M N/A N/A Dte Energy W&J-53.97 H-30.83 Meter Installation (Removal of 2-10" temporary spools and installation of 2- owner furnished meters) in East China, MI Charles Yates JR. Company W- 150.50 J- 90.50 H- 64.50 6x10 Minnesota 14361 10/4/21 W-4 J-1 or AN H-5 12/18/21 Kokomo, IN Turner, Robert S Seyler, Justin W (817) 908-8903 Nisource W&J-53.97 H-27.11 Installation of regulator station with various pipe diameters 8", 12", 16", 20", & 24" in Howard Co., Indiana Charles Yates Jr. Limited, Inc. W- 150.50 J- 90.50 H- 64.50 5x10 1x8 Minnesota 14360 10/4/21 W-2 J-AN H-2 10/23/21 Wapakoneta, OH Pattison, Joshua L Schwartz, Cory J (763) 592-9177 Dominion W&J-53.97 H-32.23 Relocation of approx. -

July/August 2020 03 DCA 2016 President Dale Anderson

THE BI-MONTHLY PUBLICATION OF THE DISTRIBUTION CONTRACTORS ASSOCIATION NEWS JULY / AUGUST 2020 Winning by an Inch Jason Dorsey Webinar PSMS Webinar War emergency pipeline from Longview, Texas to Norris City, Illinois. Moving 200 foot section of pipe welded to main line by firing line method CONTENTS 04 04 Winning by an Inch: Pipelines and Victory in World War II 08 DCA & Jason Dorsey Webinar 12 DCA Webinar With Steve Allen 08 15 DCA Fall Meeting 18 DCA Annual Convention 20 Industry News 22 22 Insights 25 Calendar 26 Member News 26 July/August 2020 03 DCA 2016 President Dale Anderson Reflections from 2016 DCA outgoing president Winning by an Inch: Pipelines and Victory in World War II At the end of World War II, people rejoiced, credited the Oil was, of course, equally important to the Allied bravery of the Allied armed forces, lauded the courage and Axis powers. Without it, there would be no gasoline and cunning of their leaders, and proclaimed, “The war for trucks, tanks, or airplanes, no lubricants for guns and was won by an inch!” machinery, and no synthetic rubber for tires or asphalt If you’ve never heard that celebratory phrase or don’t for runways. Both sides tried to maintain their own have a clue what it means, you’re not alone. Many production lifelines while cutting off the others’ supplies. things from the era are mere historical footnotes now. But here, the Allies had a clear advantage: more than What it refers to is the Big Inch and Big Little Inch half of the world’s oil was pumped from fields in the U.S. -

EAGLE STATION NUMBER 25, 20-INCH LINE VALVE WAR EMERGENCY PIPELINE HAER No

EAGLE STATION NUMBER 25, HAER No. PA-577-A 20-INCH LINE VALVE WAR EMERGENCY PIPELINE Route 100 Eagle vicinity Chester County Pennsylvania PHOTOGRAPHS WRITTEN HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE DATA HISTORIC AMERICAN ENGINEERING RECORD Southwest System Support Office National Park Service P.O. Box 728 Santa Fe, New Mexico 87504 HISTORIC AMERICAN ENGINEERING RECORD EAGLE STATION NUMBER 25, 20-INCH LINE VAL VE WAR EMERGENCY PIPELINE HAER No. PA-577-A LOCATION: Texas Eastern Transmission Corporation, Eagle Station No. 25 Route 100, Eagle vicinity, Chester County, Pennsylvania USGS Downingtown, PA, Quadrangle; UTM Coordinates: 18.441520.4438430 DATE OF CONSTRUCTION: 1942-1943 ENGINEERS: Charles P. Cathers, Defense Plants Corporation; Oscar Wolfe, War Emergency Pipelines, Inc. CONTRACTORS: War Emergency Pipelines, Inc. (WEP) BUILDER: United States Government PRESENT OWNER: Texas Eastern Transmission Corporation (TETCO), Houston, Texas ORIGINAL USE: Facilities support structure at pipeline pumping station PRESENT USE: Same, abandoned SIGNIFICANCE: The 20-Inch Line Valve at Station No. 25 is a representative example of one of the original pipeline valves used in the construction of the Inch Lines. The valve retains a high level of integrity with respect to materials and location. PROJECT INFORMATION: The Inch Lines were recorded under the provisions of a Programmatic Agreement among the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation, and the State Historic Preservation Offices of Texas, Arkansas, Missouri, Illinois, Indiana, Ohio, West Virginia, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey for the Big Inch and Little Big Inch Pipelines. The documentation was prepared for Texas Eastern Transmission Corporation by the Cultural Resource Group of Louis Berger & Associates, Inc. -

Aloha Petroleum, Ltd

Case 1:20-cv-00470-DKW-KJM Document 1 Filed 10/30/20 Page 1 of 141 PageID #: 1 GIBSON, DUNN & CRUTCHER LLP Theodore J. Boutrous, Jr., pro hac vice forthcoming [email protected] 333 South Grand Avenue Los Angeles, CA 90071 Telephone: 213.229.7000 Facsimile: 213.229.7520 WATANABE ING LLP Melvyn M. Miyagi #1624-0 [email protected] Ross T. Shinyama #8830-0 [email protected] Summer H. Kaiawe #9599-0 [email protected] 999 Bishop Street, Suite 1250 Honolulu, HI 96813 Telephone: 808.544.8300 Facsimile: 808.544.8399 Attorneys for Defendants CHEVRON CORPORATION and CHEVRON U.S.A., INC. UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF HAWAIʻI CASE NO.: 20-cv-00470 COUNTY OF MAUI, NOTICE OF REMOVAL BY Plaintiff, DEFENDANTS CHEVRON v. CORPORATION AND CHEVRON U.S.A., INC.; SUNOCO LP; ALOHA PETROLEUM, DECLARATION OF LTD.; ALOHA PETROLEUM LLC; MELVYN M. MIYAGI IN EXXON MOBIL CORP.; EXXONMOBIL SUPPORT OF NOTICE OF OIL CORPORATION; ROYAL DUTCH REMOVAL; EXHIBITS SHELL PLC; SHELL OIL COMPANY; “1” – “79”; CERTIFICATE SHELL OIL PRODUCTS COMPANY OF SERVICE LLC; CHEVRON CORP; CHEVRON USA INC.; BHP GROUP LIMITED; BHP [Removal from the Circuit Court GROUP PLC; BHP HAWAII INC.; BP of the Second Circuit, State of PLC; BP AMERICA INC.; MARATHON Hawai‘i] PETROLEUM CORP.; Case 1:20-cv-00470-DKW-KJM Document 1 Filed 10/30/20 Page 2 of 141 PageID #: 2 CONOCOPHILLIPS; CONOCOPHILLIPS COMPANY; Action Filed: October 12, 2020 PHILLIPS 66; PHILLIPS 66 COMPANY; AND DOES 1 through 100, inclusive, Defendants. TO THE CLERK OF THE ABOVE-TITLED COURT AND TO PLAINTIFF THE COUNTY OF MAUI AND ITS COUNSEL OF RECORD: PLEASE TAKE NOTICE THAT Defendants Chevron Corp. -

The Politics of Us Oil Pipelines

FINAL—11/11/16 © COPYRIGHT 2016 BY THE ENERGY BAR ASSOCIATION THE POLITICS OF U.S. OIL PIPELINES: THE FIRST BORN STRUGGLES TO LEARN FROM THE CLEVER YOUNGER SIBLING Jeff D. Makholm, Ph.D. & Laura T. W. Olive, Ph.D.* Synopsis: The regulatory treatment of oil pipelines in the United States has been on the move, as the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) at- tempts to square what it knows about regulating gas pipelines as a highly compet- itive transport business with its oil pipeline duties. Despite some useful action, however, the FERC has not been very successful: the difficulties facing the place- ment and construction of new oil pipelines have fueled history’s third boom in oil shipments by rail (despite the greater cost and risk of that mode of oil transport) and also led to a major legal and international dispute regarding the placement of a new oil pipeline (Keystone XL). The core problem for the regulation of the U.S. oil pipeline industry that frustrates the FERC’s efforts is its maladapted original regulatory legislation—written in 1906 on a railroad model and ill-suited to the technology and related industrial organization of pipelines. The FERC created a masterpiece of competition and regulatory restraint in its treatment of U.S. gas pipelines, which has helped to save U.S. consumers half a trillion dollars in their gas bills compared to Europeans in just the past six years. Burdened by that 1906 statute, however, and in a country where major legislative interventions in the oil and gas industry are rare, it seems unlikely that the FERC can mimic in oil transport the kind of competitive and regulatory success it has had in gas. -

21St Century Energy Infrastructure: Policy Recommendations for Development of American CO2 Pipeline Networks

21st Century Energy Infrastructure: Policy Recommendations for Development of American CO2 Pipeline Networks White paper prepared by the State CO2-EOR Deployment Work Group February 2017 21st Century Energy Infrastructure: Policy Recommendations for Development of American CO2 Pipeline Networks Acknowledgements While the final recommendations of this white paper represent the joint conclusions of state officials in the State CO2-EOR Deployment Work Group, participating state officials want to recognize the contributions of leading private sector stakeholders and CO2- enhanced oil recovery experts who lent their expertise and guidance to the effort. The state representatives extend their thanks to all who contributed to this white paper, and to the Hewlett Foundation for the funding that made this work possible. Page 2 Prepared by the State CO2-EOR Deployment Work Group 21st Century Energy Infrastructure: Policy Recommendations for Development of American CO2 Pipeline Networks State CO2-EOR Deployment Work Group Participant List Representatives of Co-convening Governors • Matthew Fry, Policy Advisor, Office of Wyoming Governor Matt Mead • Dan Lloyd, Business Development Specialist, Office of Montana Governor Steve Bullock Participating State Officials • Stuart Ellsworth, Engineering Manager, Colorado Oil & Gas Conservation Commission • Michael Kennedy, Assistant Director, Kentucky Energy & Environment Cabinet • Shawn Shurden, Commission Counsel, Mississippi Public Service Commission • Patrick McDonnell, Secretary, Pennsylvania Department -

Long Night of the Tankers: Hitler's War Against Caribbean

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository University of Calgary Press University of Calgary Press Open Access Books 2014 Long Night of the Tankers: Hitler’s War Against Caribbean Oil Bercuson, David J.; Herwig, Holger H. University of Calgary Press Bercuson, D. J. & Herwig, H. H. "Long Night of the Tankers: Hitler’s War Against Caribbean Oil". Beyond Boundaries: Canadian Defence and Strategic Studies Series; 4. University of Calgary Press, Calgary, Alberta, 2014. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/49998 book http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives 4.0 International Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca University of Calgary Press www.uofcpress.com LONG NIGHT OF THE TANKERS: HITLER’S WAR AGAINST CARIBBEAN OIL David J. Bercuson and Holger H. Herwig ISBN 978-1-55238-760-3 THIS BOOK IS AN OPEN ACCESS E-BOOK. It is an electronic version of a book that can be purchased in physical form through any bookseller or on-line retailer, or from our distributors. Please support this open access publication by requesting that your university purchase a print copy of this book, or by purchasing a copy yourself. If you have any questions, please contact us at [email protected] Cover Art: The artwork on the cover of this book is not open access and falls under traditional copyright provisions; it cannot be reproduced in any way without written permission of the artists and their agents. The cover can be displayed as a complete cover image for the purposes of publicizing this work, but the artwork cannot be extracted from the context of the cover of this specific work without breaching the artist’s copyright. -

Figure 1. a Photo Taken by TDW Senior Technician, Tiffany Kinsey, out on the Road to a Customer Job

Figure 1. A photo taken by TDW Senior Technician, Tiffany Kinsey, out on the road to a customer job. Chuck Harris, T.D. Williamson, USA, describes how the Big Inch and Little Big Inch pipelines contributed to victory in WWII, and changed the direction of the century-old company. ore than 70 years after the end of WWII, countless names and places are recorded in our textbooks and etched in our memories. But there are unsung heroes, too, whose Mcontributions, however meaningful, have been overlooked or largely forgotten, except by historians. Among them are two American pipelines: the Big Inch and Little Big Inch. Although they fueled the Allied effort to such an extent that experts agree victory would have been elusive without them, to most people today, they’re simply a footnote in the chronicles of WWII, overshadowed by stories of military cunning and might. However, the revolutionary impact they had on the pipeline industry endures. When they were completed in 1943, the Inch pipelines, as they were known collectively, were the heaviest, longest and largest pipelines ever built. Without specially engineered pigs, they would not have been able to operate efficiently – and T.D. Williamson, which is celebrating its centennial this year, might never have become the pipeline solutions company it is today. Massive pipeline pair completed at break-neck speed Between gasoline for tanks, trucks, planes and military vehicles, lubricants for guns, synthetic rubber for tires and asphalt for runways, it took the Allies seven billion barrels water route. Though the idea for the Big Inch and Little Big of oil to win the war in Europe. -

Tennessee Gas and Transmission's Wartime Pipeline

The Origins of a Corporate Giant: Tennessee Gas and Transmission’s Wartime Pipeline David Raley By late 1943, demand for natural gas in the heavily industrialized northern Appalachian region of the United States was outstripping supply. With local gas fields in deep decline, industries, entre- preneurs, and the federal government looked outside the region for new supplies to keep the defense plants in operation. Formed to meet these demands for gas, Tennessee Gas and Transmission (later Tenneco) rushed to build its 1,265-mile pipeline to connect Texas gas fields with the factories, plants, and homes of Appalachia. Facing labor shortages, unusually severe weather, lack of equipment, and regulatory hurdles, Tennessee struggled to finish the pipeline by the winter of 1944. The completion of the pipeline on schedule and with- in budget marks a noteworthy beginning for a company that would pioneer the conglomeration movement following World War II. From inauspicious beginnings in the 1930s, the Tennessee Gas & Transmission Company was incorporated on April 1, 1940, to bring natural gas from Louisiana to the Tennessee market by pipeline.1 Tennessee Gas encountered numerous setbacks in obtaining both reliable gas supplies and financing for its proposed pipeline. Investors were reluctant to write big checks to a new company with no experience in the gas pipeline business. Bad luck also plagued Tennessee Gas; two prominent financial backers died during the company’s formative years, damaging efforts to obtain financing. In addition to these issues, Tennessee Gas faced high regulatory hurdles in obtaining the certificate of public convenience and necessity from the Federal Power Commission (FPC) required to build its pipeline.