The Hero's Mass and the Ontological Politics of the Image

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

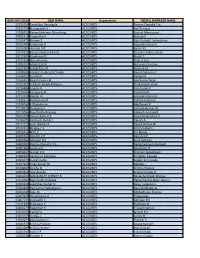

GEM SAP CODE GEM NAME Department PEOPLE MANAGER

GEM SAP CODE GEM NAME Department PEOPLE MANAGER NAME 23191950 Dorababu Derangula ACCOUNTS Poorna Chandra Trp 23157794 Kirangowda S ACCOUNTS Anil Kumara 23188751 Devendrakumar Mundaragi ACCOUNTS Govind Meesiyavar 24005319 Sangeetha P ACCOUNTS Kishore R 23205471 Naveen S ACCOUNTS Raju Polisetti Velanganee 23163149 Sivakumar R ACCOUNTS Gopalakrishnan V 23141084 Arunlal G R ACCOUNTS Jobish P J 23147333 Ramasubbaiah Pamidi ACCOUNTS Chandra Sekhar Avula 23117944 Sivakumar D ACCOUNTS Beniel T 23171294 Jibin Johnson ACCOUNTS Shiju A Jose 23183337 Ashok Sajjala ACCOUNTS Narendra Gurram 23157400 Esakki Raja M ACCOUNTS Ramesh M 23108369 Venkata Subbaiah Chukka ACCOUNTS Murali Sakamuri 23166055 Suresh N ACCOUNTS Vadivel A 23164453 Rajesh Kumar M ACCOUNTS Anil Kumar Nese 23142301 Subhash Reddy Polimera ACCOUNTS Shaikshavali Shaik 23194888 Lingam R ACCOUNTS Sasi Kumar K 23174042 Kanagaraj M ACCOUNTS Sampath M 23193190 Rakesh M ACCOUNTS Gopalakrishnan R 23140155 Kumaresan M ACCOUNTS Sathish Kumar G 23148769 K Dhinakaran ACCOUNTS Madhavan R 23118535 Kanagaraj S ACCOUNTS Saravanakumar M 23114764 Nagi Reddy Koppala ACCOUNTS Srikanth Gorlapalli 23165228 Dinesh Babu K.K ACCOUNTS Siva Subramanian P 23144676 Santhosh Kumar J ACCOUNTS Dinesh A 23122519 Selin Mehala P ACCOUNTS Rajesh Kumar M 23122212 Bhagya C S ACCOUNTS Girish Kulkarni 23159112 Binci C ACCOUNTS K P Bijuraj 23105734 Vineeth V P ACCOUNTS Rajesh A P 24003561 Abhilash B S ACCOUNTS Sunil Sathyan 23065051 Poorna Chandra Trp ACCOUNTS Ramanjaneyulu Bylupati 23207162 Saranraj K ACCOUNTS Rajendran R 24003617 -

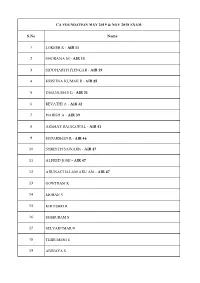

RANK App No. Name Gender Community Marks 1 358876

DCE COURSEWISE REPORT, COURSE CODE-APOT1-2021-08-18 DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE FINAL RANK LIST (TAMIL MEDIUM) RANK APPLICATION NAME GENDER COMMUNITY STREAM CUT-OFF MARKS REMARKS NO 1 309641 SACHIN KUMAR S Male MBC AND DNC HSC Academic 379.33 2 499988 AMRUTA K S Female BC HSC Academic 375.00 3 410135 MOHAN P Male MBC (V) HSC Academic 373.36 4 249284 KARUPPAIYA V Male BC HSC Academic 369.36 5 227689 PRAVINKUMAR K Male SC HSC Academic 369.00 6 289607 K.GOMATHI Female SCA HSC Academic 368.28 7 247035 L.MONIKA SABARI Female BC HSC Academic 368.24 8 421814 ARUNIKA K Female SC HSC Academic 368.00 9 359623 MANOJ M Male MBC AND DNC HSC Academic 367.97 10 425641 TAMIZHARASI.C Female SCA HSC Academic 364.04 11 222591 V.MUHIL DHARAN Male BC HSC Vocational 363.92 12 331734 AARTHI M Female BC HSC Academic 362.66 13 435155 ARULKUMAR S Male BC HSC Academic 362.25 14 248114 DHANAPRIYA P Female SC HSC Academic 362.00 15 276520 Srinath G Male SC HSC Academic 360.48 16 287526 MANIKANDAN.R Male OC HSC Academic 360.00 17 335986 KABIL M Male SC HSC Academic 359.57 18 386587 BETHANA SAMY P Male BC HSC Academic 359.36 19 250276 MADHUMITHA B Female SC HSC Academic 358.97 20 276942 DEEPAKRAHUL Male SCA HSC Academic 358.89 21 211707 A.NATHIYA Female BC HSC Academic 358.83 22 323536 M. MOUSMI Female SC HSC Academic 358.15 23 477006 NATHIYA S Female MBC (V) HSC Academic 357.87 24 364895 S. -

Harris Jayaraj Music for Dummies

Harris Jayaraj Music For Dummies Harris Jayaraj Instrumental Mp3. Title Music of Thuppakki mp3. Duration: 01:43 min. Download // Download On Android. Harris Jayaraj for Dummies mp3 Harris Jayaraj Hits Mp3 Download Latest music latest songs on PagalWorlds / DjPunjab Title Music Of Thuppakki Mp3 Harris Jayaraj For Dummies Mp3. Harris Jayaraj, Free Download MP3 Songs, Soundtrack Music, Ringtone and Listen Audio More! mp3skull waptrick juices Harris Jayaraj for Dummies. Join Facebook to connect with Harish Manoharan and others you may know. Facebook Music. Yuvan Shankar Raja · Harris Jayaraj · Ilayaraja · A.R. Rahman. Title Music of Thuppakki mp3. Duration: Harris Jayaraj for Dummies mp3 Calvin Harris - Awooga vs Justice vs Simian - We Are Your Friends (Mashup) mp3 Yennai Arindhaal - Idhayathai Yedho Ondru Video Ajith Kumar, Harris Jayaraj · Yennai Arindhaal - Idhayathai Crash Test Dummies - Mmm Mmm Mmm Mmm. Harris Jayaraj Music For Dummies Read/Download file size sort mp3punch, You can play, listen and download music for free. the podcast - soundcloud.com/parodesynoise/harris-jayaraj-for-dummies. downloadms-excel-for-dummies- books-pdf-2007-notes-in-hindi.pdf Source: Jeyaraj-tamil Christian Song mp3 youtube Harris Jayaraj Latest Telugu Best Songs. subtitrare the others 2001 divx eng (Harris Jayaraj Tamil Hits). by dokuwiki · Music moinmoin powered python powered · Bulgar newspaper tabloid filipino. download. Download harris jayaraj (320 KBPS) for free on FreeMP3 no registration is needed to download the full song. Harris Jayaraj for Dummies MP3. 196 kbps Anegan - Theme Music / Dhanush / Harris Jayaraj / KV Anand MP3. New Music · Billboard, + CHART. Blues Music · Disco Heroes are Dummies - New Trend in Tamil Cinema / Thani Oruvan, Baahubali. -

Brochure Dubbed 140909

Andhi Toofan Director : Chi Gurudutt Music : Vidyasagar Aaj Ka Krantiveer Year of release : 2008 Cast : Sudeep, Vaibhavi, Pooja Gandhi Director : Uday Shankar Synopsis : Kamanna (Doddanna) has brought up Ramanna (Sudeep) and Kittanna (Rockline Venkatesh) Music : Vidyasagar from childhood. All the three are efficient thieves. One fine day they all decide to give up their Year of release : 2001 profession of stealing and settle down in some other place. They are traveling in a lorry that develops mechanical defect in the midst of a forest on a dark night. Luckily, they find a house in the next Cast : Vijaykanth, Soundarya morning to live. This is the house of Kanaka (Vaibhavi). Her father is facing a difficult situation in front Synopsis : Vijaykant plays the role of a respected village elder Thavasi, whose word is law. He also of the village chieftain. The stay of trio in this house gives some relief and courage to the distressed plays the younger character too, that of Bhoopathy, Thavasi's son where he gets to romance - sing family. The trio - Kamanna and his two sons barge in to the chieftain's house to resolve the litigation further angers the village chieftain. and dance, and fight too. Soundarya, is cast as his fiance, whereas Jayasudha plays Thavasi's wife The trio decides to stay in this village thereafter doing cultivation. In a village fair, Ramanna ties the mangalasutra to Gayathri, daughter of and Nasser plays Pandy, Thavasi's brother-in-law and the villain of the piece. village chieftain. The village chieftain give up his harshness for the sake of his daughter Gayathri. -

Spectacle Spaces: Production of Caste in Recent Tamil Films

South Asian Popular Culture ISSN: 1474-6689 (Print) 1474-6697 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rsap20 Spectacle spaces: Production of caste in recent Tamil films Dickens Leonard To cite this article: Dickens Leonard (2015) Spectacle spaces: Production of caste in recent Tamil films, South Asian Popular Culture, 13:2, 155-173, DOI: 10.1080/14746689.2015.1088499 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14746689.2015.1088499 Published online: 23 Oct 2015. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rsap20 Download by: [University of Hyderabad] Date: 25 October 2015, At: 01:16 South Asian Popular Culture, 2015 Vol. 13, No. 2, 155–173, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14746689.2015.1088499 Spectacle spaces: Production of caste in recent Tamil films Dickens Leonard* Centre for Comparative Literature, University of Hyderabad, Hyderabad, India This paper analyses contemporary, popular Tamil films set in Madurai with respect to space and caste. These films actualize region as a cinematic imaginary through its authenticity markers – caste/ist practices explicitly, which earlier films constructed as a ‘trope’. The paper uses the concept of Heterotopias to analyse the recurrence of spectacle spaces in the construction of Madurai, and the production of caste in contemporary films. In this pursuit, it interrogates the implications of such spatial discourses. Spectacle spaces: Production of caste in recent Tamil films To foreground the study of caste in Tamil films and to link it with the rise of ‘caste- gestapo’ networks that execute honour killings and murders as a reaction to ‘inter-caste love dramas’ in Tamil Nadu,1 let me narrate a political incident that occurred in Tamil Nadu – that of the formation of a socio-political movement against Dalit assertion in December 2012. -

Results Cafoundation Cacpt

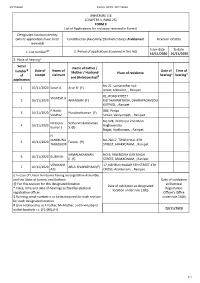

CA FOUNDATION MAY 2019 & NOV 2018 EXAM S.No Name 1 LOKESH K - AIR 11 2 SHOBANA M - AIR 15 3 SIDDHARTH IYENGAR - AIR 19 4 KRISHNA KUMAR R - AIR 25 5 DHANUSH S G - AIR 31 6 REVATHI A - AIR 32 7 HARISH A - AIR 39 8 AKSHAY RAJAGOPAL - AIR 41 9 SUDARSHAN R - AIR 46 10 SHRESTH SAWARN - AIR 47 11 ALFRED JOSE - AIR 47 12 ARUNACHALAM ARU AM - AIR 47 13 GOWTHAM K 14 MOHAN V 15 KIRTISHRI R 16 SUBBURAM S 17 SELVAKUMAR N 18 THIRUMENI E 19 ABINAYA S 20 YOKESH R 21 SANTHOSSH S 22 LOGESH S 23 SETHURAMAN S 24 SAJEETHAMBIGAI 25 JAYSUHITH TK 26 ARAVIND S 27 DHARAN KUMAR S 28 SANTHOSH P 29 SUGANTHI N 30 AHAMED BASHA T 31 MOHAMED NIYAS J 32 MOHAMMED SOHAILATHAR 33 AJAY KUMAR M 34 ASHWIN P 35 AJAY M 36 BALAJI M 37 CHANDRASEKAR V 38 AMRUDHA VARSHINI T S 39 GANESH V 40 VIVEGA V 41 PRAGATHI R 42 SURENDHER KUMAR S 43 SARAVANAN V 44 GOWTHAM G 45 SRIVATSAN A 46 NANDHINI DEVI 47 KARTHIKEYAN M 48 YAMINI V S 49 AJITH KUMAR M 50 SARAN PRASATH 51 ABINESH R 52 DESIKA A 53 MONIKA M 54 AADHITHIYA P 55 ABDULLAH TAHA 56 SANDESH A 57 BOOLIBHARATH R 58 SELVAMANI S 59 SUVEDHA R 60 HAJIRA SULTHANA D 61 PADMAVATHY S 62 SINGARAVELAN N 63 MANIKANDAN V 64 CAROLIN ROSE C 65 AAKASH A 66 SANKARA NARAYANAN V 67 DHEVIYA S 68 RAHITH R 69 DINESH V 70 GAYATHRE J 71 SIVA KUMAR S 72 SHALINI SIVAKUMAR 73 KARTHICK B 74 ISHWARYA G 75 SRIKANTH V 76 MAHALAKSHMI C 77 AMRITHA PRIYADHARSHINI 78 ABIRAMI V 79 SHARMILA C K 80 SUJITHA R 81 VINAY D 82 GURUPRASATH 83 VIJAY MANI K 84 BASKARAN S 85 OVIYA N 86 LEON NOEL M 87 AFFAN JAWEED GUNDU 88 PRASANNA RAMANAA MV 89 DINESH M 90 MOHAMED ANSAR 91 SREEKANTH -

Sep 22 from 6.00 Pm to 9.00 Pm: Ravanodbhavam with Sadanam Balakrishnan (Kalanilayam) As Ravanan

Brought to you by September 22nd - 29th Service Square ChennaiThisWeek Click below for the latest on the city’s happenings Movies Concerts Exhibitions Deals Food & Drink Getaways Sunitha’s Column Services Classifields Who needs mirrors at home, when your floors are polished by us! It’s easy - use your Service Square Membership If you wish to subscribe to our weekly bulletin, please mail us at [email protected] Call 2225355 / 98849 12349 You can also view this bulletin online at http://chennai.servicesquare.in Our address - 5, Balaji Nagar, 1st Main Road, Ekkattuthangal, Chennai – 600 035 Brought to you by September M o v i e s i n C i t y M u l t i p l e x e s 22nd - 29th ChennaiThisWeek Service Square Escape Cinemas - From 23rd Sep ExpresssEscape Avenue Mall, CinemasThousand Lights, Ph:4224 4224 Movie Language Screen Show Timing Crazy Stupid Love English Blush-110 1.00 pm Body Guard Hindi Blush-110 4.00 pm Contagion English Blush-110 7.20 pm Warrior English Blush-110 10.10 pm Mausam Hindi Weave-110 12.20 & 3.50 pm Abduction English Weave-110 7.30 & 10.20 pm Engeyum Eppothum Tamil Spot-120 12.40,3.50,7.00 & 10.30 pm Final Destination English Streak-310 1.10 pm Vanthaan Vendraan Tamil Streak-310 3.30 & 10.15 pm Mausam Hindi Streak-310 6.45 pm Mankata Tamil Plush-310 11.45 am & 10.30 pm Mausam Dookodu Telugu Plush-310 3.15 & 6.50 pm Final Destination Ayiram Vilakku Tamil Frame-120 1.00 pm The Zoo Keeper English Frame-120 4.30 pm Speedy Singhs English Frame-120 7.15 pm New Final Destination English Frame-120 10.20 pm Mere Brother Ki -

Sounds of Madras USB Booklet

A R RAHMAN 16 Parandhu Sella Vaa 1 Saarattu Vandiyila O Kadhal Kanmani Kaatru Veliyidai 17 Manamaganin Sathiyam 2 Mental Manadhil Kochadaiiyaan O Kadhal Kanmani 18 Nallai Allai 3 Mersalaayitten Kaatru Veliyidai I 19 Innum Konjam Naeram 4 Sandi Kuthirai Maryan Kaaviyathalaivan 20 Moongil Thottam 5 Sonapareeya Kadal Maryan 21 Omana Penne 6 Elay Keechan Vinnaithaandi Varuvaayaa Kadal 22 Marudaani 7 Azhagiye Sakkarakatti Kaatru Veliyidai 23 Sonnalum 8 Ladio Kaadhal Virus I 24 Ae Maanpuru Mangaiyae 9 Kadal Raasa Naan Guru (Tamil) Maryan 25 Adiye 10 Kedakkari Kadal Raavanan 26 Naane Varugiraen 11 Anbil Avan O Kadhal Kanmani Vinnaithaandi Varuvaayaa 27 Ye Ye Enna Aachu 12 Chinnamma Chilakamma Kaadhal Virus Sakkarakatti 28 Kannukkul Kannai 13 Nanare Vinnaithaandi Varuvaayaa Guru (Tamil) 29 Veera 14 Aye Sinamika Raavanan O Kadhal Kanmani 30 Hosanna 15 Yaarumilla Vinnaithaandi Varuvaayaa Kaaviyathalaivan 31 Aaruyirae 45 Maanja Guru (Tamil) Maan Karate 32 Theera Ulaa 46 Hey O Kadhal Kanmani Vanakkam Chennai 33 Idhayam 47 Sirikkadhey Kochadaiiyaan Remo 34 Vinnaithaandi Varuvaayaa 48 Nee Paartha Vizhigal - The Touch of Love Vinnaithaandi Varuvaayaa 3 35 Usure pogudhey 49 Ailasa Ailasa Raavanan Vanakkam Chennai 36 Paarkaadhey Oru Madhiri 50 Boomi Enna Suthudhe Ambikapathy Ethir Neechal 37 Nenjae Yezhu 51 Oh Penne Maryan Vanakkam Chennai 52 Enakenna Yaarum Illaye ANIRUDH R Aakko 38 Oh Oh - The First Love of Tamizh 53 Tak Bak - The Tak Bak of Tamizh Thangamagan Thangamagan 39 Remo Nee Kadhalan 54 Osaka Osaka Remo Vanakkam Chennai 40 Don’u Don’u Don’u -

Influence of Celebrity Endorsement of Advertisement on Students

PJAEE, 17(6) (2020) CELEBRITY ENDORSEMENT AND EMOTIONAL APPEAL: A STUDY ON ADVERTISEMENTS BY POPULAR TAMIL CINEMA ACTORS Dr. Rajesh R Head, Department of Visual Communication, Faculty of Science and Humanities, SRM Institute of Science and Technology Kattankulathur- 603 203, Chengalpattu Dist., Tamil Nadu, INDIA Dr. Rajesh R, Celebrity Endorsement And Emotional Appeal: A Study On Advertisements By Popular Tamil Cinema Actors– Palarch’s Journal of Archaeology of Egypt/Egyptology 17(6) (2020). ISSN 1567-214X. Keywords: Celebrity, Endorsement, Advertising, Tamil Cinema, Emotional Appeal. Abstract: Advertising industries have executed various techniques in persuading customers to increase constructive responses about their products and services. Celebrity endorsement, one such popular advertising technique employed in influencing the customers. The construction of Brand or Product promotion that engages a popular personality using the reputation of the Brand, Product, or service is known as celebrity endorsement. That is, a celebrity endorsement is a promotional approach of a brand or product recommended by the famous person in the society to the customers or buyers. Here, the notable thing is that the celebrity endorses the brand or product powerfully evoking emotional feelings instead of usual appeal to the customers. In the fast movie world, the public likely to pay less attention to any advertisements in printed or visual form but optimistically get noticed when the advertisements are referred or recommended by their favorite celebrity. People in country like India, always grace about their stars from sports, politics, and particularly from the film industry. This article analyzes and evaluates various celebrity endorsements and emotional appeal, particularly the Tamil cinema actors. -

NT All Pages 2019.Indd

MEDLEY MONDAY 2 25 FEBRUARY 2019 SPPORTSORTS & FIITNESSTNESS CHENNAI 25 KANNE LKG TO LET FEBFEB BIG KALAIMAANE SCREEN BBashBaasshh GAUTHAM VASUDEV MENON Jothi Cinema Hall, Luxe, Kasi Theatre, Udhayam Theatres, Jothi Cinema Hall, Luxe, Kasi Theatre, AGS Cinemas, Albert Theatres, PVR Velacheri, Kumaran Udhayam Theatres, Sri Murugan Carnival Cinemas EVP, Devi Cineplex, Theatre, Kamala Cinemas, INOX Cinemas, PVR, Kumaran Theatre, AVM Ega Cinema, INOX, Kasi Talkies, Virugambakkam, Aradhana Rajeswari Theatre, Kamala Cinemas, Luxe Cinemas, Mayajaal, PVR, Rakki Theatre, PVR Grand Galada, Sri INOX Virugambakkam, Aradhana Theatre, Multiplex, Sangam, Sivasakthi Theatre, Lakshmi Theatre, PVR Skywalk. GK Cinemas. SPI Cinemas, Udhayam Theatre. Gautham Vasudev Menon, also known as GVM, is a film director, screenwriter and producer who predominantly works in little hands, Tamil cinema. He has also directed Hindi and Telugu fi lms, which are remakes of his own Tamil fi lms. Many of his fi lms have been critically acclaimed, most notably his romantic fi lms Minnale, Vaaranam Aayiram, Vinnaithaandi Varuvaayaa and his thrillers Kaakha Kaakha, Vettaiyaadu Vilaiyaadu and Yennai Arindhaal. Vaaranam Aayiram won the National Film Award for Best Feature Film in Tamil. mighty strength Menon produces fi lms through his Photon Kathaas fi lm production company. His production Thanga Meengal won the National Film Award for Best Feature Film in Tamil. 6-year-old Chennai lad excels in karate, aims to become boxer PREMJI AMARAN | PRAVEEN KUMAR S | pair, the minor now has a bronze Premji and a silver medal to his name. Amaran is onviction, a word to describe The latter was acquired recently a playback singer, the drive people have in at a tourney held in Royapettah. -

ANNEXURE 5.8 (CHAPTER V, PARA 25) FORM 9 List of Applica Ons For

23/11/2020 Form9_AC38_23/11/2020 ANNEXURE 5.8 (CHAPTER V, PARA 25) FORM 9 List of Applicaons for inclusion received in Form 6 Designated locaon identy (where applicaons have been Constuency (Assembly/£Parliamentary): Arakkonam Revision identy received) From date To date @ 2. Period of applicaons (covered in this list) 1. List number 16/11/2020 16/11/2020 3. Place of hearing* Serial Name of Father / $ Date of Name of Date of Time of number Mother / Husband Place of residence of receipt claimant hearing* hearing* and (Relaonship)# applicaon No 21, somanathar koil 1 16/11/2020 Saran A Arun D (F) street, takkolam, , Ranipet 01, ROAD STREET VIGNESH A 2 16/11/2020 ANANDAN (F) KILITHANPATTARAI, DHARAPADAVEDU KATPADI, , Ranipet P Harsh 804, Periya 3 16/11/2020 Purushothaman (F) Vardhan Street, Vaniyampet, , Ranipet No 128, 2nd Cross 2nd Main Niranjan Sethu Venkataraman 4 16/11/2020 Raghavendra Kumar S S (F) Nagar, Arakkonam, , Ranipet N MAIMUNA No 28/17, TOWN HALL 4TH 5 16/11/2020 Farook (H) TABASSUM STREET, ARAKKONAM, , Ranipet KAMALAKANNAN NO 9, RAJENDIRA GIRI SINGH 6 16/11/2020 RUBINI K E (F) STREET, ARAKKONAM, , Ranipet VENMANI 17, NEHRUJI NAGAR 5TH STREET 4TH 7 16/11/2020 ARUL SIVAPATHAM (F) A D CROSS, Arakkonam, , Ranipet £ In case of Union territories having no Legislave Assembly and the State of Jammu and Kashmir Date of exhibion @ For this revision for this designated locaon at Electoral Date of exhibion at designated * Place, me and date of hearings as fixed by electoral Registraon locaon under rule 15(b) registraon officer Officer’s Office $ Running serial number is to be maintained for each revision under rule 16(b) for each designated locaon # Give relaonship as F-Father, M=Mother, and H=Husband within brackets i.e. -

Goa Full Tamil Movie Download

Goa Full Tamil Movie Download Goa Full Tamil Movie Download 1 / 3 2 / 3 Goa is a 2010 Tamil language comedy film written and directed by Venkat Prabhu, who with the ... goa tamil movie ... Download Goa.2010.. GOA [2010] Download Tamil Movie 1CD Rip [High Quality - 700MB][Xvid]. [Real TC] GOA [2010] Download Tamil Movie 1CD Rip [High Quality .... Download Goa movie (2003) to your Hungama account. Watch Goa movie full online. Check out full movie Goa download, movies counter, new online movies in .... Goa is a Kannada comedy drama, starring Komal Kumar, Tharun Chandra, Srikanth, Sharmila ... Watch Goa a/an Kannada Comedy full movie on Hotstar now.. Goa is a 2010 Tamil language comedy film written and directed by Venkat Prabhu, who with the ..... The movie showed highly positive return and initially topped at the box office ..... Create a book · Download as PDF · Printable version .... Movie, : Goa (2010). Director, : Venkat Prabhu. Starring, : Jai, Premgi Amaren, Vaibhav Reddy. Genres, : Comedy. Quality, : Original DVD. Language, : Tamil.. Goa. 2010; Tamil; Comedy; HD. Play. Share. Favourite. Rate this movie ... For this, they run away to Goa in the hope of finding and getting married to rich foreign .... Pitch Perfect 3 Movie Download Torrent Watch Free full HD movies 1080p . Bombay ... Goa tamil full movie hd free download Raja Bhai Lagey Raho 1 blu-ray .. TamilGun is a illegal public torrent website. TamilGun website uploads the pirated versions of Tamil movies online for download on their site. TamilGun also .... Tags › Goa (2010) Watch Tamil Movie Online Lotus DVDRip. thumbnail. Goa (2010) HD DVD 720p Tamil Full Movie Watch Online.