Chris Van Allsburg

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Caldecott Medal 2021

Caldecott Medal Books oppl.org/kids-lists The Caldecott Medal is awarded annually by the Association for Library Service to Children. It is given to the illustrator of the most distinguished American picture book published the preceding year. The name of Randolph Caldecott, an English illustrator of books for children, was chosen for the medal because his work best represented the “joyousness of picture books as well as their beauty.” The horseman on the medal is taken from one of Caldecott’s illustrations for “The Diverting History of John Gilpin” (1878). The medal was originally donated by publisher Frederic G. Melcher (1879–1963), and is now donated by his son, Daniel. 1939 Mei Li Handforth 1972 One Fine Day Hogrogian 1940 Abraham Lincoln d’Aulaire 1973 The Funny Little Woman Lent 1941 They Were Strong and Good Lawson 1974 Duffy and the Devil Zemach 1942 Make Way for Ducklings McCloskey 1975 Arrow to the Sun McDermott 1943 The Little House Burton 1976 Why Mosquitoes Buzz in 1944 Many Moons Slobodkin People’s Ears Dillon 1945 Prayer for a Child Jones 1977 Ashanti to Zulu: 1946 The Rooster Crows Petersham African Traditions Dillon 1947 The Little Island Weisgard 1978 Noah’s Ark Spier 1948 White Snow, Bright Snow Duvoisin 1979 Girl Who Loved Wild Horses Goble 1949 The Big Snow Hader 1980 Ox-Cart Man Cooney 1950 Song of the Swallows Politi 1981 Fables Lobel 1951 The Egg Tree Milhous 1982 Jumanji Van Allsburg 1952 Finders Keepers Mordvinoff 1983 Shadow Brown 1953 The Biggest Bear Ward 1984 The Glorious Flight Provensen 1954 Madeline’s Rescue -

Caldecott Medal Winners

C A L D E C O T T 1951 The Egg Tree by Katherine Milhous 1943 The Little House by Virginia Lee Burton M EDAL 1942 Make Way for Ducklings by Robert INNERS 1950 Song of the Swallows by Leo Politi W McCloskey 1949 The Big Snow by Berta and Elmer Hader 1941 They Were Strong and Good by Robert Law- son The Caldecott Medal is awarded annually by the Association of Library Service to Children, a divi- 1948 White Snow, Bright Snow by Alvin Tres- 1940 Abraham Lincoln by Ingri Parin D’Aulaire sion of the American Library Association, to the illustrator of the most distinguished American pic- selt, ill by Roger Duvoisin 1939 Mei Li by Thomas Handforth ture book for children. The medal honors Randolph Caldecott, a famous English illustrator of children’s 1938 Animals of the Bible by Helen D. Fish, 1947 The Little Island by Golden MacDonald ill by Dorothy Lathrop 2011 A Sick Day for Amos McGee ill Erin Stead Ill by Leonard Weisgard 2010 The Lion and the Mouse by Jerry Pinkney 2009 The House in the Night by Susan Swanson 1946 Rooster Crows by Maud and Miska Peter- 2008 The Invention of Hugo Cabaret by Brian Sel- znik sham 2007 Flotsam by David Wiesner 2006 The Hello, Goodbye Window by Chris Raschka 2005 Kitten’s First Full Moon by Kevin Henkes 1945 Prayer for a Child by Rachel Field, 2004 The Man Who Walked between Two Towers by Mordicai Gerstein Ill by Elizabeth Orton Jones 2003 My Friend Rabbit by Eric Rohmann 2002 The Three Pigs by David Wiesner 2001 So You Want to Be President by Judith 1944 Many Moons by James Thruber, Ill by St.George 2000 Joseph Had A little Overcoat by Simms Tabak Louis Slobodkin 1999 Snowflake Bentley by Jacqueline Briggs Mar- tin 1998 Rapunzel by Paul O. -

1. Jumanji: Welcome to the Jungle $19.50Mn 2. 12 Strong $15.81Mn 3

xxx 14 Thursday, January 25, 2018 Thursday, January 25, 2018 15 Kelly Clarkson @kelly_clarkson Every artist wants to feel proud of the footprint they leave behind. This is my best footprint yet #MeaningOfLife Los Angeles fashion and my tastes. merican pop star Nick Jonas And then in addition to that, Asays he always travels with a the pieces that I know I’ll need Paris productions like “Asterix and Obelisk: suit just in case he needs to wear when I’m travelling,” Jonas told ctors Monica Bellucci and Jean-Paul Mission Cleopatra” and “The Apartment” one. Jonas, 25, who has teamed GQ magazine. Belmondo will be guests of honour with her long-time partner Vincent Cassel up with designer John Varvatos “That’s great black denim, forA the 23rd edition of The Lumiere and her international breakout feature, to launch a new clothing line, white sneakers, and great basics - Academy awards. Gaspar Noe’s “Irreversible.” spends a large chunk of his grey T-shirts, white T-shirts,” he The event will take place on February 5 The award focuses mainly on time in travelling. He says that added. (IANS) at the Arab World Institute here. contributions to French cinema. But the a suit is the one item he can’t The distinction as guests of honour Academy will also pay tribute to Belluci’s leave home without, reports is reserved for actors whose work has decades-long international career as femalefirst.co.uk. helped illuminate French cinema across well, including the 2015 James Bond “I work with a great stylist the world, reports variety.com. -

The Books That Are Caldecott Honors Winners Will Be Marked with a Spine Label

2013 “THIS IS NOT MY HAT” EASY K 2014 “LOCOMOTIVE” J 385.097 FLOCA 2015 “ADVENTURES OF BEEKLE” EASY S 2016 “FINDING WINNIE: THE TRUE STORY OF THE WORL’DS MOST FAMOUS BEAR” The books that are Caldecott medal winners will be marked with a spine label. The books that are Caldecott Honors winners will be marked with a spine label. Kingsport Public Library 400 Broad Street Kingsport, TN 37660 www.kingsportlibrary.org (423) 229-9366 Updated 4/22/2015 The Caldecott Medal was named in honor of nineteenth-century English 1962 “ONCE A MOUSE” EASY B 1990 “LON PO PO: A RED-RIDING illustrator Randolph Caldecott. It is 1963 “THE SNOWY DAY” EASY K HOOD STORY FROM CHINA” awarded annually by the Association 1964 “WHERE THE WILD THINGS ARE” EASY S J 398.2 Young for Library Service to Children, a 1991 “BLACK AND WHITE” EASY M division of the American Library 1965 “MAY I BRING A FRIEND” EASY D Association, to the artist of the most 1966 “ALWAYS ROOM FOR ONE MORE” 1992 “TUESDAY” EASY W distinguished American picture book EASY L 1993 “MIRETTE ON THE HIGH WIRE” for children. 1967 “SAM, BANGS & MOONSHINE” EASY M 1938 “ANIMALS OF THE BIBLE” 1968 “DRUMMER HOFF” EASY E 1994 “GRANDFATHER’S JOURNEY” J 220.8 Lathrop 1969 “THE FOOL OF THE WORLD & THE EASY S 1939 “MEI LI” Easy H FLYING SHIP” 1995 “SMOKY NIGHT” 1940 “ARAHAM LINCOLN” JB Lincoln 1970 “SYLVESTER AND THE MAGIC PEBBLE” 1996 “OFFICER BUCKLE AND 1941 “THEY WERE STRONG AND EASY A GLORIA” EASY R GOOD” J 920 LAWSON 1971 “A STORY-A STORY: AN AFRICAN TALE” 1997 “GOLEM” EASY W 1942 “MAKE WAY FOR DUCKLINGS” J 398.2 Haley EASY M 1972 “ONE FINE DAY” EASY H 1998 “RAPUNZEL” EASY Z 1943 “THE LITTLE HOUSE” 1973 “THE FUNNY LITTLE WOMAN” EASY M 1999 “SNOWFLAKE BENTLEY” 1944 “MANY MOONS” EASY T 1974 “DUFFY AND THE DEVIL” J 551.5784 MARTIN 1945 “PRAYER FOR A CHILD” 1975 “ARROW TO THE SUN” 2000 “JOSEPH HAD A LITTLE J 242.62 Field OVERCOAT” EASY T 1976 “WHY MOSQUITOES BUZZ IN PEOPLE’S 1946 “THE ROOSTER CROWS” EASY P 2001 “SO YOU WANT TO BE PRESI- EARS” EASY A DENT” J 973.099 St. -

(ALSC) Caldecott Medal & Honor Books, 1938 to Present

Association for Library Service to Children (ALSC) Caldecott Medal & Honor Books, 1938 to present 2014 Medal Winner: Locomotive, written and illustrated by Brian Floca (Atheneum Books for Young Readers, an imprint of Simon & Schuster Children’s Publishing) 2014 Honor Books: Journey, written and illustrated by Aaron Becker (Candlewick Press) Flora and the Flamingo, written and illustrated by Molly Idle (Chronicle Books) Mr. Wuffles! written and illustrated by David Wiesner (Clarion Books, an imprint of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing) 2013 Medal Winner: This Is Not My Hat, written and illustrated by Jon Klassen (Candlewick Press) 2013 Honor Books: Creepy Carrots!, illustrated by Peter Brown, written by Aaron Reynolds (Simon & Schuster Books for Young Readers, an imprint of Simon & Schuster Children’s Publishing Division) Extra Yarn, illustrated by Jon Klassen, written by Mac Barnett (Balzer + Bray, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers) Green, illustrated and written by Laura Vaccaro Seeger (Neal Porter Books, an imprint of Roaring Brook Press) One Cool Friend, illustrated by David Small, written by Toni Buzzeo (Dial Books for Young Readers, a division of Penguin Young Readers Group) Sleep Like a Tiger, illustrated by Pamela Zagarenski, written by Mary Logue (Houghton Mifflin Books for Children, an imprint of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company) 2012 Medal Winner: A Ball for Daisy by Chris Raschka (Schwartz & Wade Books, an imprint of Random House Children's Books, a division of Random House, Inc.) 2013 Honor Books: Blackout by John Rocco (Disney · Hyperion Books, an imprint of Disney Book Group) Grandpa Green by Lane Smith (Roaring Brook Press, a division of Holtzbrinck Publishing Holdings Limited Partnership) Me...Jane by Patrick McDonnell (Little, Brown and Company, a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc.) 2011 Medal Winner: A Sick Day for Amos McGee, illustrated by Erin E. -

Award Winning Books (508) 531-1304

EDUCATIONAL RESOURCE CENTER Clement C. Maxwell Library 10 Shaw Road Bridgewater MA 02324 AWARD WINNING BOOKS (508) 531-1304 http://www.bridgew.edu/library/ Revised: May 2013 cml Table of Contents Caldecott Medal Winners………………………. 1 Newbery Medal Winners……………………….. 5 Coretta Scott King Award Winners…………. 9 Mildred Batchelder Award Winners……….. 11 Phoenix Award Winners………………………… 13 Theodor Seuss Geisel Award Winners…….. 14 CALDECOTT MEDAL WINNERS The Caldecott Medal was established in 1938 and named in honor of nineteenth-century English illustrator Randolph Caldecott. It is awarded annually to the illustrator of the most distinguished American picture book for children published in the previous year. Location Call # Award Year Pic K634t This is Not My Hat. John Klassen. (Candlewick Press) Grades K-2. A little fish thinks he 2013 can get away with stealing a hat. Pic R223b A Ball for Daisy. Chris Raschka. (Random House Children’s Books) Grades preschool-2. A 2012 gray and white puppy and her red ball are constant companions until a poodle inadvertently deflates the toy. Pic S7992s A Sick Day for Amos McGee. Philip C. Stead. (Roaring Brook Press) Grades preschool-1. 2011 The best sick day ever and the animals in the zoo feature in this striking picture book. Pic P655l The Lion and the Mouse. Jerry Pinkney. (Little, Brown and Company) Grades preschool- 2010 1. A wordless retelling of the Aesop fable set in the African Serengeti. Pic S9728h The House in the Night. Susan Marie Swanson. (Houghton Mifflin) Grades preschool-1. 2009 Illustrations and easy text explore what makes a house in the night a home filled with light. -

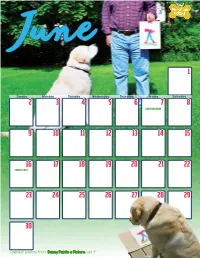

Calendar Photos from Danny Paints a Picture, Set 4 June 2019 Cut and Paste Activity Calendar Activity

June 1 Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Dad’s birthDay 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 Father’s Day 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 Calendar photos from Danny Paints a Picture, set 4 June 2019 Cut and Paste Activity Calendar Activity Find the June birthdays, cut out the picture that goes with each, and paste it on their special day on the calendar. 6 Cynthia Rylant was born June 6, 1954 in West Virginia. Her youth in the Appalachian region provided the setting for her first children’s book, When I was Young in the Mountains. A prolific writer of children’s literature, Rylant explores themes of friendship, emotions, and growing up. She has been awarded the Newbery Medal for A Fine White Dust, and several other stories have been named Newbery Honor and Caldecott Honor books. 10 The writer and illustrator of the popular Where the Wild Things Are, Maurice Sendak was born June 10, 1928. First an illustrator, Sendak worked on more than eighty books written by various authors before he wrote his own story. Kenny’s Window, published in 1956, was Sendak’s first title of which he was both author and illustrator. Seven years later he produced Where the Wild Things Are and earned the Caldecott Medal. 18 Another Caldecott Medal winner is Chris Van Allsburg. Born June 18, 1949, Allsburg is best known as the author and illustrator of Jumanji and The Polar Express, both of which have been made into major motion pictures. -

Zathura: a Space Adventure

An intergalactic world of wonder is waiting just outside your front door in Columbia Pictures' heart-racing sci-fi family film Zathura: A Space Adventure. Zathura: A Space Adventure is the story of two squabbling brothers who are propelled into deepest, darkest space while playing a mysterious game they discovered in the basement of their old house. Now, they must overcome their differences and work together to complete the game or they will be trapped in outer space forever. SYNOPSIS After their father ( Tim Robbins ) leaves for work, leaving them in the care of their older sister ( Kristen Stewart ), six year-old Danny ( Jonah Bobo ) and ten-year old Walter ( Josh Hutcherson ) either get on each other‘s nerves or are totally bored. When their bickering escalates and Walter starts chasing him, Danny hides in a dumbwaiter. But Walter surprises him, and in retaliation, lowers Danny into their dark, scary basement, where he discovers an old tattered metal board game, —Zathura.“ After trying unsuccessfully to get his brother to play the game with him, Danny starts to play on his own. From his first move, Danny realizes this is no ordinary board game. His spaceship marker moves by itself and when it lands on a space, a card is ejected, which reads: —Meteor shower, take evasive action.“ The house is immediately pummeled from above by hot, molten meteors. When Danny and Walter look up through the gaping hole in their roof, they discover, to their horror, that they have been propelled into deepest, darkest outer space. And they are not alone. -

Jumanji 3 4 Novelization by Todd Strasser 5 Based on the Screenplay and Screen Story Based on the Book by Chris Van Allsburg 6

Penguin Readers Factsheets level E Teacher’s notes 1 2 Jumanji 3 4 Novelization by Todd Strasser 5 Based on the screenplay and screen story based on the book by Chris Van Allsburg 6 ELEMENTARY SUMMARY ‘That game is too dangerous for children to play!’ says Alan Parrish. Alan Parrish should know. He played the THEMES IN VAN ALLSBURG’S NOVELS game in 1969 and disappeared! Jumanji is a story for All Van Allsburg’s books have uncertain boundaries children about a very strange game - a game that between reality and fantasy, or dream, and contain a becomes far too real and frightening for the players. It was puzzle element. The deepest puzzle in his books is - are originally a story by Chris Van Allsburg. It was released as the events real or are they fantasy? For children, the world a film in 1996, starring the famous American actor Robin of the imagination is very real. The boundaries between Williams. the imagination and the real world are not yet firmly in The story begins in 1869 in New Hampshire, America. place. The author’s stories make these uncertain Two young brothers bury a box under some trees. They boundaries very explicit - his stories are consequently fear that someone will find the box some time - ‘Then God both confusing and exciting. JUMANJI help them,’ says one of the boys. A hundred years later, in Van Allsburg’s stories often narrate a quest (a long 1969, a boy, Alan Parrish, finds the box and takes it home. search). The hero or heroes set out on an adventure that He’s unhappy; his father wants to send him to boarding changes them in some way for the better, and teaches school. -

Hail to the Caldecott!

Children the journal of the Association for Library Service to Children Libraries & Volume 11 Number 1 Spring 2013 ISSN 1542-9806 Hail to the Caldecott! Interviews with Winners Selznick and Wiesner • Rare Historic Banquet Photos • Getting ‘The Call’ PERMIT NO. 4 NO. PERMIT Change Service Requested Service Change HANOVER, PA HANOVER, Chicago, Illinois 60611 Illinois Chicago, PAID 50 East Huron Street Huron East 50 U.S. POSTAGE POSTAGE U.S. Association for Library Service to Children to Service Library for Association NONPROFIT ORG. NONPROFIT PENGUIN celebrates 75 YEARS of the CALDECOTT MEDAL! PENGUIN YOUNG READERS GROUP PenguinClassroom.com PenguinClassroom PenguinClass Table Contents● ofVolume 11, Number 1 Spring 2013 Notes 50 Caldecott 2.0? Caldecott Titles in the Digital Age 3 Guest Editor’s Note Cen Campbell Julie Cummins 52 Beneath the Gold Foil Seal 6 President’s Message Meet the Caldecott-Winning Artists Online Carolyn S. Brodie Danika Brubaker Features Departments 9 The “Caldecott Effect” 41 Call for Referees The Powerful Impact of Those “Shiny Stickers” Vicky Smith 53 Author Guidelines 14 Who Was Randolph Caldecott? 54 ALSC News The Man Behind the Award 63 Index to Advertisers Leonard S. Marcus 64 The Last Word 18 Small Details, Huge Impact Bee Thorpe A Chat with Three-Time Caldecott Winner David Wiesner Sharon Verbeten 21 A “Felt” Thing An Editor’s-Eye View of the Caldecott Patricia Lee Gauch 29 Getting “The Call” Caldecott Winners Remember That Moment Nick Glass 35 Hugo Cabret, From Page to Screen An Interview with Brian Selznick Jennifer M. Brown 39 Caldecott Honored at Eric Carle Museum 40 Caldecott’s Lost Gravesite . -

Chris Van Allsburg Genre

Chris Van Allsburg, author and illustrator Author/Illustrator: Chris Van Allsburg Genre: Children's Fantasy Novel Biography: Van Allsburg He was born in Grand Rapids, MiChigan in June 18th, 1949. His seCond home was in the housing development outside of Grand Rapids that resembled the house he illustrated in Polar Express. • He attended University of MiChigan and got a degree in SCulpture. He got seleCted into the Art Program without a portfolio but beCause of his response to a Question from the university interviewer asking him what he thought about Norman RoCkwell. He, “off the Cuff” answered (QuiCkly thinking that the interviewer was a big fan of this artist) “I believe Norman RoCkwell is unfairly CritiCized for being sentimental. I think he is a wonderful painter who Captures AmeriCa's longings. AmeriCa's dreams and present AmeriCan life with the drama and sensitivity of great playwright"(22). The admission offiCer was very impressed and aCCepted Chris into the program right on the spot. • On an interview with Chris, he expressed that he always enjoyed drawing, but growing up in Grand Rapids his talent wasn’t enCouraged as muCh as sports and athletiCs was. But soon his teaChers and peers were amazed at his artistiC talent and in high sChool drew a lot for the sChool. Chris Continues to say that his drawing developed in Combination with his love for story telling through piCtures. He Created stories by asking Questions to himself “What if” and “what then”. For example, the way he Created Jumanji was asking two Questions: What if two Children were bored while at home and disCover a board game and then what would happen if the board Came alive? He won the CaldeCott Honor Medal for this book in 1980. -

Caldecott Medal Winners

Hey, Al by Arthur Yorinks (1987) Why Mosquitoes Buzz in People's Ears by Caldecott Location: Picture Book Yorinks Verna Aardema (1976) Location: Picture Book Tales Why The Polar Express by Chris Van Allsburg Medal (1986) Arrow to the Sun by Gerald McDermott Location: Kids Holiday Christmas Van Allsburg (1975) Location: Picture Book Tales Arrow Winners Saint George and the Dragon by Marga- ret Hodges (1985) Duffy and the Devil by Harve Zemach Location: Kids 398.2342 Hodges (1974) The Randolph Caldecott Medal is awarded Location: Picture Book Tales Duffy Shadow by Blaise Cendrars annually by the Association for Library Service (1983) The Funny Little Woman by Arlene Mosel to Children to “the artist of the most distin- Location: Picture Book Tales (1973) guished American picture book for children.” Shadow Location: Picture Book Tales Funny One Fine Day by Nonny Hogrogian (1972) Jumanji by Chris Van Allsburg (1982) Location: Picture Book Hogrogian Location: Kids Illustrated Fiction Van Allsburg A Story A Story: An African Tale by Gail E. Fables by Arnold Lobel (1981) Haley (1971) Location: Picture Book Tales Collection Location: Picture Book Tales Story Ox-Cart Man by Donald Hall (1980) Sylvester and the Magic Pebble Location: Picture Book Hall by William Steig (1970) Location: Picture Book Steig The Girl Who Loved Wild Horses by Paul Goble (1979) Location: Picture Book Tales Girl Noah's Ark by Peter Spier (1978) Wilmington Memorial Library Location: Picture Book Spier 175 Middlesex Ave Ashanti to Zulu: African Traditions by Wilmington, MA 01887 Margaret Musgrove (1977) wilmlibrary.org/kids Location: Kids 960 Musgrove Youth Services: 978-694-2098 Wolf in the Snow by Matthew The Invention of Hugo Cabret by Brian Rapunzel by Paul O.