Canaries in the Mines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Allied Campaign Blasts Military Installations

Cyan EDITION: XXXX Yellow Magenta Black K EXTRA NEXT UPDATES will be available in vending boxes at noon and 4:30 p.m. TheVindicator Monday, October 8, 2001 www.vindy.com 35 cents AMERICA FIGHTS War on Afghan terrorism begins Allied campaign blasts military installations “Initially, the terrorists may burrow deeper into The war aims to eradicate caves and other entrenched hiding places,” he said. “Our military action is also designed to clear the way for sustained, comprehensive and relentless opera- terrorist networks. tions to drive them out and bring them to justice.” COMBINED DISPATCHES Osama bin Laden, the mastermind behind the Sept. Anti-terror fight Britain promises Taped message 11 attacks on America, vowed new terror in a state- ment videotaped from his hiding place, presumably in American and British forces struck Afghanistan, and released Sunday. has just begun, to fight beside has purpose: Bin Laden was not specifically a target in Sunday’s at- Afghanistan with a massive military bar- tacks, according to Defense Secretary Donald Rums- Bush declares U.S. forces motivation rage Sunday, unleashing the first pun- feld. He said the war on terror aims at much bigger ishing assault in a war to destroy the ter- targets than bin Laden alone: the eradication of ter- rorist networks. The Taliban had a chance to British submarines have joined Bin Laden insists that the mili- rorists who attacked the United States Food air-dropped: In addition, some 35,000 rations tary assault is a war on Islam. on Sept. 11 and the radical Islamic of food and medical supplies were air-dropped for the meet demands, Bush said. -

Icelebrfttio

Series touts solid, functionaLfamily B13 Mark Pattison/CNS NEW YORK (CNS)-The fol WASHINGTON — It's good that TVReview lowing are reviews of video and Americans can see a solid, function § DVD releases from the Office ing family on the WB series "7th Mary's College in Notre Dame, Ind. for Fflm& Broadcasting of the Heaven," said Catherine Hicks, the She then won an acting fellowship ? U.S. Conference of Catholic Catholic actress who pla'ys Annie and earned a master's degree in fine Bishops. Classifications do not Camden, the mother of seven on the arts at Cornell University in Ithaca, take into account the extra con- series. N.Y. - r, tentin DVD releases, which has It plays in sharp contrast to the Originally in TV soap operas as a u ' zr not been reviewed. prevalence of divorce in the United professional actress, Hicks parlayed c 'ANTWONE FISHER' States. "It's breaking the heart of the playing Marilyn Monroe in a made- nation," she told Catholic News Ser for-TV movie into a lead role in the Inspirational true-life story of vice in a telephone interview from • short-lived series, "Tucker's Witch." a troubled naval recruit (Derek the "7th Heaven" set in Hollywood. For much of the decade before her ' Luke) who with the help of a "Divorce, divorce, divorce,," she daughter, Catie, was bornrin 1992, Navy psychiatrist (Denzel added; "It's broken the hearts of she had featured rdles in several TV ' Washington) learns to cope with thousands of families. '7th Heaven' series and movies. She took two the emotional devastation is sort of an image of a functioning -years off after Catfie's birth before wreakedt>y childhood rejection family that's not going to break up." returning to the screen. -

Summer/Fall 2021 Brochure

Program Guide Because of the COVID 19 pandemic summer/fall activities have been modified until further notice. Parks & Recreation Parks Where funisserious business. Summer/Fall 2021 Summer/Fall ANNUAL MEMBERSHIP RATES $159 In District $179 Out of District SENIORS (55 or BETTER) ADULT FITNESS – 2 ADULT $75 In District $179 Out of District STUDENT MEMBERSHIP* $89 In District $179 Out of District Annual rates include Community Center Come check us out! & Gym Memberships Inspiration “This isn’t just where I workout, Membership Requirements Energy it’s where I belong.” Accomplishment Adults 18 years and older Proof of Park District residency for In District rates: - Drivers License or State ID Premium Locker Rooms Day Pass $15 In District $30 Out of District Indoor Track The Center Operating Hours Mon. - Thur. 5 AM - 7 PM Friday 5 AM - 5 PM Saturday 6 AM - 1 PM Community Relationship & Support Sunday CLOSED Hours subject to change 3101 Washington Blvd., Bellwood, IL 60104 • 708-547-5400 x4 SPONSOR COMMUNITY THIS EVENT! FISHING DERBY Saturday, September 18, 2021 8 AM to 11 AM Catch a live fish for dinner. Stevenson Pond 3101 Washington Blvd. Bellwood, Illinois Hot Dogs Sponsored by the Bellwood Lions Club PRIZES! For The Largest & Smallest Fish Caught On The Hour BRING YOUR ROD, REEL AND BAIT! FOR INFORMATION CALL 708-547-3900 x4 Visit www.mempark.org • Email: [email protected] REGISTRATION – 3 REGISTRATION REGISTRATION CREDIT Registration for most classes and activities may be done by mail, 1. No Cash Refunds. fax, or in person. 2. Credit will be issued to persons withdrawing from park district programs. -

8 RE2 CFP 3-13-09.Indd

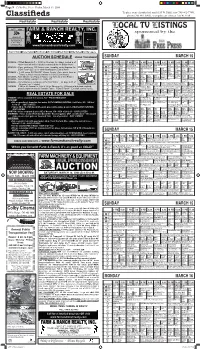

SATURDAY MARCH 14 6 PM 6:30 7 PM 7:30 8 PM 8:30 9 PM 9:30 10 PM 10:30 11 PM 11:30 KLBY/ABC News (N) Kake Dancing With the Stars (CC) Castle Flowers for News Desperate Ent. H h (CC) News Your Grave (CC) (CC) Housewives (CC) Tonight KSNK/NBC News (N) Wheel of The Celebrity Apprentice (CC) Law & Order By News (N) Saturday Night Live Tracy L j Fortune Perjury (CC) Morgan; Kelly Clarkson. (CC) KBSL/CBSSATURDAYCollege Basketball: NCIS Agent Afloat The Mentalist The 48 Hours Mystery News (N) CatchMARCH it Boston Legal14 The 1< NX Pac-10 Final (CC) Thin Red Line (CC) (CC) (CC) Kansas Ass Fat Jungle (CC) K15CG How to Beat the The Welk Stars: Through the Years Great Performances The Car- Soundstage Seal d Bogey6 PM Man 6:30 7 PM 7:30 8 PM 8:30 Police9 P MCertifiable9:30 (CC) 10 PM henge10:30 (CC)11 PM 11:30 KLBY/ABCESPN NewsCollege (N) Basketball:Kake DancingCollege GameDay With the StarsCollege (CC) Basketball: BigCastle East FlowersTournament for SportsCenterNews Desperate (Live) Midnight Fast-Ent. HO_h (CC)Big 12 FinalNews (Live) (CC) Final -- Teams TBA. NewYour York. Grave (Live) (CC) (CC)(CC) HousewivesMadness (CC) breakTonight KSNK/NBCUSA News(5:30) (N)Movie:Wheel How of to TheLose Celebrity a Guy in Apprentice10 Movie: (CC) The Skeleton KeyLaw TTZ& Order (2005, By LawNews & (N)Order:Saturday NightLaw & Live Order: Tracy SVU LP^j Days TT (2003)Fortune Kate Hudson. (CC) Suspense) Kate Hudson.Perjury (Premiere) (CC) (CC) Criminal IntentMorgan; Kelly Clarkson. -

As Writers of Film and Television and Members of the Writers Guild Of

July 20, 2021 As writers of film and television and members of the Writers Guild of America, East and Writers Guild of America West, we understand the critical importance of a union contract. We are proud to stand in support of the editorial staff at MSNBC who have chosen to organize with the Writers Guild of America, East. We welcome you to the Guild and the labor movement. We encourage everyone to vote YES in the upcoming election so you can get to the bargaining table to have a say in your future. We work in scripted television and film, including many projects produced by NBC Universal. Through our union membership we have been able to negotiate fair compensation, excellent benefits, and basic fairness at work—all of which are enshrined in our union contract. We are ready to support you in your effort to do the same. We’re all in this together. Vote Union YES! In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (THE DEUCE) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS) Daniel Abraham (THE EXPANSE) David Abramowitz (CAGNEY AND LACEY; HIGHLANDER; DAUGHTER OF THE STREETS) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; MR. BELVEDERE; THE PARKERS) Gayle Abrams (FASIER; GILMORE GIRLS; 8 SIMPLE RULES) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEEPER) Peter Ackerman (THINGS YOU SHOULDN'T SAY PAST MIDNIGHT; ICE AGE; THE AMERICANS) Joan Ackermann (ARLISS) 1 Ilunga Adell (SANFORD & SON; WATCH YOUR MOUTH; MY BROTHER & ME) Dayo Adesokan (SUPERSTORE; YOUNG & HUNGRY; DOWNWARD DOG) Jonathan Adler (THE TONIGHT SHOW STARRING JIMMY FALLON) Erik Agard (THE CHASE) Zaike Airey (SWEET TOOTH) Rory Albanese (THE DAILY SHOW WITH JON STEWART; THE NIGHTLY SHOW WITH LARRY WILMORE) Chris Albers (LATE NIGHT WITH CONAN O'BRIEN; BORGIA) Lisa Albert (MAD MEN; HALT AND CATCH FIRE; UNREAL) Jerome Albrecht (THE LOVE BOAT) Georgianna Aldaco (MIRACLE WORKERS) Robert Alden (STREETWALKIN') Richard Alfieri (SIX DANCE LESSONS IN SIX WEEKS) Stephanie Allain (DEAR WHITE PEOPLE) A.C. -

Other 3/1/04 Pg 5

Colby Free Press Monday, March 1, 2004 Page 5 Debate continues about transportation’s future By JOHN HANNA budget, the state diverted $165 mil- Miller noted a projected deficit “A follow-on plan will be nearly AP Political Writer lion and set aside no sales tax rev- would exist even without Sebelius’ impossible,” he said, speaking of TOPEKA (AP) — Discussions enues for transportation. plan. Also, she said, the state faced the next potential transportation about transportation at the State- The result is a gaping hole in a similar situation in 1998, when the program. house this year have an almost pan- funding for the program and 1989 program ended, and legisla- Miller’s biggest fear is that icky tone. Miller’s threat to cancel $550 mil- tors knew it would arise again even- KDOT will have to cancel projects Many lawmakers and officials in lion worth of projects over five tually when they approved the 1999 and will lose so much credibility Gov. Kathleen Sebelius’ adminis- years. program. that legislators will not want to pur- tration argue that the Legislature Under the 1999 legislation, the But initial projections in 1999 sue a new, post-2009 program. Do- must act now to save the state’s state is supposed to set aside 12 per- showed the deficit occurring at least ing nothing, raising too little money comprehensive transportation pro- cent of its sales tax revenues to a year later. Kerr said Sebelius’ ad- to bolster the program, or failing to gram from collapse. transportation. Sebelius proposes ministration is managing the cur- deliver promised revenues in the Transportation Secretary Deb resuming the set-aside in 2006 but rent program so that “it just kind of near future all could cause her to Miller has even promised to start then only 3 percent of sales tax rev- crashes” when it ends. -

Janet Weinberg, Ace ~ Editor

JANET WEINBERG, ACE ~ EDITOR "THE BABY-SITTERS CLUB" 2019, 2021 Netflix and Walden Media Half hour episodic - Season 1 & 2 EP: Rachel Shukert “SEX/LIFE” 2020-2021 Netflix Hour episodic – Season 1 EP: Stacy Rukeyser “INTERROGATION” 2019 CBS All Access Hour episodic – Season 1 EPs: John Mankiewicz, Anders Weidemann “LITTLE AMERICA” 2019 Universal for Apple Half hour episodic – Season 1 EPs: Lee Eisenberg, Sian Heder "THE EDGE OF SEVENTEEN" 2019 STX for YouTube Half-hour – Pilot EP/Director: Annabele Oaks “BETTER THINGS” 2018-2019 FX Half hour episodic – Season 3 EP/Director: Pamela Adlon ACE Eddie Award Winner For S3 Episode 8 “UnREAL” 2014-2018 A&E for Lifetime Hour episodic – Seasons 1-3 EPs: Bob Sertner, Sarah Shapiro, Stacy Rukeyser, Marti Noxon “THE EXORCIST” 2016-2017 Fox Studio for Fox Hour episodic – Seasons 1&2 Executive Producers: Rolin Jones, Jeremy Slater “JANE THE VIRGIN” 2015-2016 CBS Studio for the CW Hour episodic – Season 2 Executive Producer: Jennie Snyder Urman “MISTRESSES” 2015 ABC Studio for ABC Hour episodic – Season 2 EPs: Bob Sertner, Rina Mimoun, K.J. Steinberg “DEVIOUS MAIDS” 2012-2014 ABC Studio for Lifetime Hour episodic – Seasons 1&2 Executive Producer: Marc Cherry “CHASING LIFE” 2013-2014 Lionsgate and ABC for ABC Family Hour episodic – Seasons 1&2 Executive Producer: Patrick Sean Smith “THE LYING GAME” 2011-2012 Warner Horizon for ABC Family Hour episodic – Seasons 1-3 Executive Producer: Chuck Pratt 4929 Wilshire Blvd., Ste. 259 Los Angeles, CA 90010 ph 323.782.1854 fx 323.345.5690 [email protected] “Secret Life of the American Teenager” ABC Studio for ABC Family 2008-2010 Executive Producer: Brenda Hampton Pilot and Seasons 1&2 Director: Ron Underwood (pilot) “7th Heaven” 1996-2007 Spelling TV for The WB/CBS, for The CW Seasons 1-11 – 114 episodes EPs: Aaron Spelling, Brenda Hampton “Love Boat: The Next Wave” Spelling TV for UPN Hour episodic – Season 1 Executive Producer: Aaron Spelling “Next of Kin” 2005 Directed by Stephen Collins Theatrical short (numerous festival awards) “Spenser: For Hire” Warner Bros. -

Curriculum Download

CURRICULUM Christine Aufderhaar graduated in classical piano performance (Conservatory Lugano), classical composition and film scoring (Berklee College of Music, Boston). Upon completion she lived in Los Angeles and worked within a mentorship program with the composers Alf Clausen (‚The Simpson’), Jay Chattaway (‚Star Trek’) and Steve Bramson (‚J.A.G.’). Christine was honored with several awards and scholarships (Germany, Switzerland and USA). Her compositions have been performed in the USA as well as in Europe. Christine currently lives in Berlin, where she writes and produces music for film and television. From 2004 to 2008 she was Associate Professor at the The Film and Television University „Konrad Wolf“ (HFF) in Potsdam Babelsberg (Berlin). Since 2007 she works exclusively as a composer. Christine is member of the German Film Academy and the Academy of German Music Authors. 2014 MEMBER OF THE ACADEMY OF GERMAN MUSIC AUTHORS 2009 MEMBER OF THE GERMAN FILM ACADEMY 2004-2008 ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR FOR FILM SCORING at the Film University Babelsberg Konrad Wolf 2006 Invitation as one of 12 composers selected for the INTERNATIONAL ASCAP FILM SCORING WORKSHOP, Los Angeles 2002 Invitation as one of four composers selected for the international ‘MENTORSHIP PROGRAM’ of the ‘SOCIETY OF COMPOSERS AND LYRICISTS’, Los Angeles (Members at the time: J. Goldsmith, D. Raksin, E. Bernstein etc.), which consists of working with leading composers such as Alf Clausen („The Simpsons“), Jay Chattaway („Star Trek“), Steve Bramson („JAG“) and Dan Foliart (“7th Heaven”). 1999-2001 BERKLEE COLLEGE of Music, Boston, degree in double major film scoring and classical composition, ‘summa cum laude’. Graduation in two instead of the usual five years. -

Board of Park Commissioners Board Meeting Minutes

NOT POSTED Joe Doud Administration Building 545 Academy Drive Board of Park Commissioners Northbrook, IL 60062 Board Meeting Minutes 847-291-2960 nbparks.org MINUTES of the Board Meeting of the Northbrook Park District Board of Commissioners held at an in-person meeting on Wednesday, July 28, 2021 in the Joe Doud Administration Building, 545 Academy Drive, Northbrook, Illinois. CALL TO ORDER AND ROLL CALL President Chambers called the Regular Board Meeting to order at 7:00pm. Commissioners Present: President Chambers; Vice President Chalem; Commissioners Goodman, Schyman, Simon (via conference call; left at 7:56pm) and Ziering Commissioner Absent: Commissioner Curin Officers Present: Executive Director Hamer; Treasurer Munn; Assistant Secretary Peterson Staff Present: Directors Baron, Dalton, Loftus and Scovic; Specialist Scharp (left at 7:44pm); Parks Division Manager Kosbab (left at 7:44pm) RECOGNITION OF VISITORS Mary Reynolds – League of Women Voters (left at 7:44pm) APPROVAL OF AMENDED AGENDA President Chambers called to amend the Agenda to add discussion under VII. New Business 3401 Commercial Avenue – Cook County 6b Program request and a Closed Session after Item XI. President Report. Vice President Chalem made a motion to amend the Agenda to add discussion under VII. New Business 3401 Commercial Avenue – Cook County 6b Program request and add a Closed Session after Item XI. President Report to Discuss the Purchase or Lease of Real Property for the Use of the Public Body, Including Meetings Held for the Purpose of Discussing Whether a Particular Parcel Should Be Acquired. 5 ILCS 120/2(c)(5). Commissioner Simon seconded the motion to amend the Agenda. -

San Diego County Treasurer-Tax Collector 2019-2020 Returned Property Tax Bills

SAN DIEGO COUNTY TREASURER-TAX COLLECTOR 2019-2020 RETURNED PROPERTY TAX BILLS TO SEARCH, PRESS "CTRL + F" CLICK HERE TO CHANGE MAILING ADDRESS PARCEL/BILL OWNER NAME 8579002100 11-11 GIFT TRUST 04-01-96 8579002104 11-11 GIFT TRUST 04-01-96 8579002112 11-11 GIFT TRUST 04-01-96 8679002101 11-11 GIFT TRUST 04-01-96 8679002105 11-11 GIFT TRUST 04-01-96 8679002113 11-11 GIFT TRUST 04-01-96 8779002102 11-11 GIFT TRUST 04-01-96 8779002106 11-11 GIFT TRUST 04-01-96 8779002114 11-11 GIFT TRUST 04-01-96 8879002103 11-11 GIFT TRUST 04-01-96 8879002107 11-11 GIFT TRUST 04-01-96 8879002115 11-11 GIFT TRUST 04-01-96 5331250200 1141 LAGUNA AVE L L C 2224832400 1201 VIA RAFAEL LTD 3172710300 12150 FLINT PLACE LLC 2350405100 1282 PACIFIC OAKS LLC 4891237400 1360 E MADISON AVENUE L L C 1780235100 138 SUN VILLA CT LLC 8894504458 138 SUN VILLA CT LLC 2222400700 1488 SAN PABLO L L C 1300500500 15195 HWY 76 TRUST 04-084 1473500900 152 S MYERS LLC 4230941300 1550 GARNET LLC 2754610900 15632 POMERADO ROAD L L C 1678 COUNTRY CLUB DR ESCONDIDO CA 92029 TRUST 05-07- 2325114700 18 1678 COUNTRY CLUB DR ESCONDIDO CA 92029 TRUST 05-07- 8894616148 18 2542212300 1697A LA COSTA MEADOWS L L C 2542212400 1697A LA COSTA MEADOWS L L C 6461901900 1704 CACTUS ROAD LLC 5333021200 1750 FIFTH AVENUE L L C 2542304001 180 PHOEBE STREET LLC 5392130600 1815-19 GRANADA AVENUE LLC 5392130700 1815-19 GRANADA AVENUE LLC 2643515400 18503 CALLE LA SERRA L L C 2263601300 1991 TRUST 12-02-91 AND W J K FAMILY LTD PARTNERSHIP 5650321400 1998 ENG FAMILY L L C 5683522300 1998 ENG FAMILY L L -

Rhetoric and Agency of the Revolutionary Association of the Women of Afghanistan Lauren M

University of Texas at El Paso DigitalCommons@UTEP Open Access Theses & Dissertations 2014-01-01 Constructing a Participatory Citizenship: Rhetoric and Agency of the Revolutionary Association of the Women of Afghanistan Lauren M. Connolly University of Texas at El Paso, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.utep.edu/open_etd Part of the Rhetoric Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Connolly, Lauren M., "Constructing a Participatory Citizenship: Rhetoric and Agency of the Revolutionary Association of the Women of Afghanistan" (2014). Open Access Theses & Dissertations. 1222. https://digitalcommons.utep.edu/open_etd/1222 This is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UTEP. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UTEP. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CONSTRUCTING A PARTICIPATORY CITIZENSHIP: RHETORIC AND AGENCY OF THE REVOLUTIONARY ASSOCIATION OF THE WOMEN OF AFGHANISTAN by LAUREN MARIE BOSTROM CONNOLLY, B.A., M.A. APPROVED: Kate Mangelsdorf, Ph.D., Chair Beth Brunk-Chavez, Ph.D. Maggy Smith, Ph.D. Brenda Risch, Ph.D. Bess Sirmon-Taylor, Ph.D. Interim Dean of the Graduate School Copyright © by Lauren M. Connolly 2014 DEDICATION To Hugo and Tersila CONSTRUCTING A PARTICIPATORY CITIZENSHIP: RHETORIC AND AGENCY OF THE REVOLUTIONARY ASSOCIATION OF THE WOMEN OF AFGHANISTAN by LAUREN MARIE BOSTROM CONNOLLY, B.A., M.A. DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at El Paso in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of English THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT EL PASO May 2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS DEDICATION ............................................................................................................................. -

7Th Heaven Free Download

7TH HEAVEN FREE DOWNLOAD James Patterson,Maxine Paetro | 383 pages | 01 Dec 2009 | Time Warner Trade Publishing | 9780446536240 | English | New York, United States 7th Heaven 2.2.3.522 Fun between the sheets! You can quickly try out a mod and keep or uninstall it without affecting your game installation. This category only includes cookies that ensures basic functionalities and security features of the website. User Reviews "Nice" characters fail to make drama ignite 18 November by 7th Heaven — See all my reviews. Q: Whate are the lyrics to the theme song? Children Welcome. Simon went to college, and 7th Heaven married and pursued his career as a doctor. Rocks [Download with ] or manual download: 7th Heaven 2 14 MB. An element of chaos. Some range from the traumatic e. The show's already ultra low budget was moderately trimmed, 7th Heaven salary cuts among the 7th Heaven and some episodes to be filmed in six 7th Heaven, instead of seven. Help Learn to edit Community portal Recent changes Upload file. In region 2, seasons have been released while in region 4 the first 6 seasons have been released on DVD. Eco Tourism. Water Sports. Complete my Booking. Categories : s American teen drama television series s American drama television series American television series debuts s American teen 7th Heaven television series s American drama television series American television series endings American primetime television 7th Heaven American primetime television soap operas American television soap operas Christian entertainment television series The CW original programming English-language television shows Teenage pregnancy in television Television shows set in California Television series about families Television series by CBS Television Studios Television series by Spelling Television The WB original programming Television series created by Brenda Hampton Religious drama television series.