Accompaniment and Welcome

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Blessings During a Pandemic

JESUITS Central and Southern Fall 2020 The Mission Continues: Blessings during a Pandemic Virtual Spirituality | Jubilarians | 40 Years of JRS MESSAGE FROM THE PROVINCIAL Dear Friends in the Lord, Queridos hermanos en el Señor. This year the Jesuit Refugee Service Este año, el Servicio Jesuita a Refugiados (SJR) celebra 40 años (JRS) celebrates 40 years of service, de servicio, educación y defensa a los refugiados. La Provincia education and advocacy to refugees. USA Central y Meridional ha apoyado al SJR desde sus inicios The USA Central and Southern contribuyendo con nuestros hombres y recursos. Quienes que Province has supported JRS since its han trabajado con el SJR dirían que recibieron tanto como inception by contributing our men dieron. Conmemoramos con profunda gratitud cuatro décadas and resources. Those who have served de aprendizaje e inspiración con los refugiados. Y sé que ese es with JRS would say that they received mi caso. just as much as they gave. We com- En el 2001 tuve la oportunidad de trabajar con el SJR en memorate with deep gratitude 40 years of learning from and el campamento Dzaleka en Malawi. En ese momento, el VIH- being inspired by refugees. I know that is the case for me. SIDA estaba devastando el África subsahariana, incluido el In 2001 I had the opportunity to work with JRS in campamento de Dzaleka. Una de las escenas conmovedoras que Dzaleka Camp in Malawi. At that time, HIV-AIDS was recuerdo es la imagen de los refugiados reunidos en círculo al ravaging sub-Saharan Africa, including Dzaleka Camp. One final del día alrededor de una pequeña fogata, compartiendo sus of the poignant scenes that sticks in my mind is the image exiguas raciones mensuales de arroz y frijoles, y disfrutando de of refugees gathered in a circle at the end of the day around la mutua compañía. -

Jesuit Urban Mission

Jesuit Urban Mission Bernard loved the hills, Benedict the valleys, Francis the towns, Ignatius great cities. This brief couplet of unknown origin captures in a few words the distinct charisms of four saints and founders of religious communities in the Church— the Cistercians, the Benedictines, the Franciscans and the Jesuits. Ignatius of Loyola, who founded the Society of Jesus (the Jesuits), placed much focus on the plight of the poor in the great cities of his time. In his Spiritual Exercises, Ignatius imagined God gazing upon the teeming masses of our cities, on men and women sick and dying, the old and young, the rich and the poor, the happy and sad, some being born and some being laid to rest. Surrounded by that mass of human need, Ignatius was 63 moved by a God who joyfully opted to 60 At Rome he founds public works of piety: hospices for In Rome, he renews the practice of frequenting women in bad marriages; for virgins at [the church of] step into the pain of human suffering and the sacraments and of giving devout sermons and Santa Caterina dei Funari, for [orphan] girls at [the became flesh, sharing fully all our human introduces ways of passing on the rudiments of church of] Santi Quattro Coronati, also for orphan Christian doctrine to youth in the churches and boys wandering through the city as beggars, a residence joys and sorrows. squares of Rome. Peter Balais, S.J. Plates 60, 63. Vita beati patris Ignatii Loiolae for [Jewish] catechumens, as well as other residences The Illustrated Life of Ignatius of Loyola, and colleges, to the profit and with the admiration of Jesuit Refugee Service published in Rome in 1609 to celebrate Ignatius’ beatification that year by Pope Paul V. -

Way of the Cross Jesuit Refugee Service This Photo and Cover Photo: the Way of the Cross, Yei, South Sudan

Way of the Cross Jesuit Refugee Service This photo and cover photo: The Way of the Cross, Yei, South Sudan. (Angela Hellmuth — Jesuit Refugee Service) Jesuit Refugee Service/USA www.jrsusa.org Jesuit Refugee Service/USA www.jrsusa.org PRELUDE: Then Jesus came with them to a place called Gethsemane, and he said to his disciples, "Sit here while I go over there and pray." … Then he said to them, "My soul is sorrowful even to death. Remain here and keep watch with me." He advanced a little and fell prostrate in prayer, saying, "My Father, if it is possible, let this cup pass from me; yet, not as I will, but as you will." When he returned to his disciples he found them asleep. He said to Peter, "So you could not keep watch with me for one hour? Watch and pray that you may not undergo the test. The spirit is willing, but the flesh is weak." (Matthew 26:37-41) Reflection: Christ calls us to keep watch. Let us accompany Jesus on this journey as we watch and pray over all that is go- ing on with many of our sisters and brothers around the world. STATION ONE: JESUS IS CONDEMNED TO DEATH All: We adore you, O Christ, and we bless you because by your holy cross you have redeemed the world. Pilate said to them, “Then what shall I do with Jesus called Messi- ah?” They all said, “Let him be crucified!” But he said, “Why? What evil has he done?” They only shouted the louder, “Let him be cruci- fied!” When Pilate saw that he was not succeeding at all, but that a riot was breaking out instead, he took water and washed his hands in the sight of the crowd, saying, “I am innocent of this man’s blood. -

GOD in EXILE Towards a Shared Spirituality with Refugees

GOD IN EXILE Towards a shared spirituality with refugees Jesuit Refugee Service 160 GOD IN EXILE Towards a shared spirituality with refugees Jesuit Refugee Service 1 Jesuit Refugee Service (JRS) is an international Catholic organization with a mission to accompany, serve and plead the cause of refugees and forcibly displaced people. Se up by the Society of Jesus in 1980 and now at work in over 50 countries, the priority of JRS is to accompany refugees whose needs are more urgent or forgotten. © Jesuit Refugee Service, October 2005 ISBN: 88-88126-02-3 Editorial team: Pablo Alonso SJ, Jacques Haers SJ, Elías López SJ, Lluís Magriñà SJ, Danielle Vella Production: Stefano Maero Cover design: Stefano Maero Cover photo: Amaya Valcárcel/JRS Biblical quotes in this book have been taken from the New Revised Standard Version Bible: Anglicized Edition, copyright 1989, 1995, Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved. Copies of this book and CD are available from: Jesuit Refugee Service C.P. 6139, 00195 Roma Prati, Italy Tel.: +39 – 06.68.97.73.86 Fax: +39 – 06.68.80.64.18 Email: [email protected] JRS website: http://www.jrs.net 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreward 5 Introduction 9 Chapter 1 ‘FOR GOD HAS ALSO LOST A SON’ 15 A biblical perspective Chapter 2 BREAKING BREAD TOGETHER 29 Accompanying refugees Chapter 3 RESTORING HUMAN DIGNITY 59 Serving refugees Chapter 4 GOD’S WORK HAS NO BORDERS 87 Defending the cause of refugees Chapter 5 STRONG ENOUGH OR WEAK ENOUGH? 121 Spirituality matters Appendix 1 IGNATIUS OF LOYOLA 140 Appendix 2 GLOSSARY OF IGNATIAN TERMS 149 3 Don Doll SJ/JRS 4 FOREWARD God in Exile: Towards a Shared Spirituality with Refugees is intended for people involved in the mission of Jesuit Refugee Service (JRS) and others who serve refugees and people on the move. -

Address of His Holiness Pope Francis Meeting with the Jesuit Refugee Service Vatican, November 14, 2015

Address of His Holiness Pope Francis Meeting with the Jesuit Refugee Service Vatican, November 14, 2015 Dear Brothers and Sisters, I am happy to receive you on this, the thirty-fifth anniversary of the establishment of the Jesuit Refugee Service envisaged by Father Pedro Arrupe, then the Superior General of the Society of Jesus. The profound impact made on him by the plight of the South Vietnamese boat people, exposed to pirate attacks and storms in the South China Sea, was what led him to undertake this initiative. Father Arrupe, who had lived through the atomic bomb explosion at Hiroshima, realized the scope of that tragic exodus of refugees. He saw it as a challenge which the Jesuits could not ignore if they were to remain faithful to their vocation. He wanted the Jesuit Refugee Service to meet both the human and the spiritual needs of refugees, not only their immediate need of food and shelter, but also their need to see their human dignity respected, to be listened to and comforted. The phenomenon of forced migration has dramatically increased in the meantime. Crowds of refugees are leaving different countries of the Middle East, Africa and Asia, to seek refuge in Europe. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees has estimated that there are, worldwide, almost sixty million refugees, the highest number since the Second World War. Behind these statistics are people, each of them with a name, a face, a story, an inalienable dignity which is theirs as a child of God. At present, you are active in ten different regions, with projects in forty-five countries, through which you provide services to refugees and peoples in internal migrations. -

New Call from the Society of Jesus to Support JRS

SPRING 2019 VOL XX NO 3 JESUIT REFUGEE SERVICE accompany | serve | advocate link New Call from the Society of Jesus to support JRS In May 2019, Father Arturo Sosa, the of the most punitive policies affecting that the “mission of JRS must be Superior General of the Society of people seeking asylum in the world.” shared by all our institutions…[This] Jesus, renewed the Jesuit Society’s On multiple occasions, the United shared mission of reconciliation and commitment to JRS. In a letter entitled Nations, as well as Jesuit and other justice...dedicates itself anew to the “Renewed Commitment of the Jesuit Catholic leaders have condemned accompaniment, service, and defence Refugee Service” that was addressed Australia for inhumane treatment of of refugees around the world.” We “To the Whole Society of Jesus and many people seeking protection. These wish to thank you, our friends and Partners in Mission,” Fr General are the policies that JRS Australia seeks collaborators, for sharing this mission outlined the realities of the current to influence, each and every day, the with JRS and for walking with us. policies that result in so many women, global refugee crisis in explaining Father Arturo Sosa, the Superior the necessity for full support for men and children suffering. General of the Society of Jesus JRS. “With such grave and urgent Fr General quotes Pope Francis who needs, JRS must strive to be even has called on the international more effective in its programmes and community to have a shared response advocacy.” to refugees and migrants that can “No one can be unaware of the many be articulated in four verbs “to political movements that stoke welcome, to protect, to promote and resentment against refugees for to integrate.” Pope Francis has also electoral gain,” wrote Fr General. -

English Classes in Bamyan, Afghanistan

1 To give a child a seat at school is the finest gift you can give. (Address of Pope Francis to the Jesuit Refugee Service, 14 November 2015) Publisher Cover photo Photo credits Thomas H. Smolich SJ A teacher and her student in For JRS: the Kaya Refugee Camp in Louie Bacomo, Martina Editorial team Maban County, South Sudan. Bezzini, Orville Desilva SJ, JRS International Office The camp shelters thousands Gorka Ortega, Yves Rene of refugees from the Blue Shema. Designer Nile region. JRS provides Koen Ivens educational and psychosocial Photos on pages 1, 8, 20 services to both refugees and and 22 courtesy of Denis the host community. (Paul Bosnic, Christian Fuchs, Jeffrey/Misean Cara) Salat Albareed, and Paul Jeffrey for Misean Cara. 2 An internally displaced girl studies at a JRS school in Kachin State, Myanmar Table of contents Who we are 3 Our context 4 Responding to a call 5 Map of people served 6 Serving refugees during a time of unprecedented displacement 9 • Education 9 • Livelihoods 13 • Psychosocial support 17 • Emergency humanitarian assistance: focus on Syria 19 The Global Education Initiative 23 Financial summary 26 International Director’s message 28 Stay informed and support JRS 29 1 2 JRS staff in Jibreen, Syria. Who we are 37 years of serving refugees Our mission around the world Inspired by the generous love De facto refugees The Jesuit Refugee Service and example of Jesus Christ, (JRS) is a Catholic organisation JRS seeks to accompany, JRS believes that the founded in 1980 by the Society serve, and advocate the cause definition of a “refugee” of Jesus to respond to the of refugees and other forcibly according to international plight of Vietnamese refugees displaced people, that they may conventions is too restrictive, fleeing their war-ravaged heal, learn, and determine their and ignores the needs of homeland. -

The Jesuit Refugee Service and the Ministry of Accompaniment

Consolation in action: the Jesuit Refugee Service and the ministry of accompaniment Author: Kevin O'Brien Persistent link: http://hdl.handle.net/2345/bc-ir:106760 This work is posted on eScholarship@BC, Boston College University Libraries. : Weston Jesuit School of Theology, 2006 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2016 https://archive.org/details/consolationinactOOobri CONSOLATION IN ACTION The Jesuit Refugee Service and the Ministry of Accompaniment A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the S.T.L. degree of Weston Jesuit School of Theology, Cambridge, Massachusetts S.T.L. Candidate: Kevin O’Brien, S.J. Thesis Director: John O’Malley, S.J. Second Reader: Kevin Burke, S.J. / May 2006 ViSSTOaJ OV' Ti^LlOfiY LiBRARIf S9 {SF.ATTLE STREET CA^^BRIDGE, ivlASS. 02138 Contents Introduction 1 Chapter 1: The Story of JRS as a Jesuit Ministry 7 Roots of JRS in Jesuit History 8 Foundation of JRS 13 Arrupe’s “Swan Song” 15 JRS After Arrupe 17 Expansion of JRS Around the World 18 JRS Charter of 2000 24 Mission of JRS Today 25 JRS and Education 29 Conclusion 32 Chapter 2: Accompaniment as the Practice of Solidarity 34 Solidarity as a Social Principle and Moral Virtue 35 Solidarity as Accompanying the Poor and Powerless 41 JRS and Refugees Bearing One Another’s Burdens 47 Conclusion 54 Chapter 3: JRS and the Spiritual Exercises 55 Accompanying Jesus through the Exercises 56 Taking Crucified Peoples Down from their Crosses 60 Witnessing to the Hope of the Resurrection 65 Conclusion 68 Chapter 4: JRS as an Embodiment of the -

The Jesuits and Globalization

THE JESUITS AND GLOBALIZATION Historical Legacies and Contemporary Challenges THOMAS BA CHOFF AND JOSE CASANOVA, Editors Georgetown University Press Washington, DC b f 20lb Gt:'O~"C'I()\\ U UPI\ ('''11'1 f)f AU ngbl rC'K'f~d ~o PJrI of Ihl1. ~l: m,lY be rc:p,OfJuu·J Of uUlltC'd In .In) form or by ,n)'IlK'.uu. declroPic or me h.ltu II. IndudlO~ pholU< If''Int: .and I't' cwdll1g. Of b)' an)" In(orm'Cl(m I n~e'~nd R'cnC',1I, 'I('nt, wuhout J"C'fmlcon In \Hllmg from the pub!"hcr. JOles: O~nchofT.ThonuJ F. 19(too$cdllor l ~n(J\.;I.}<Kc.ah(l;)r T1UC'ThCJC'iUlb .1Odg1ob.tJlZ'Jflon hl\umuJ lep In.and CiPmC'mf'Ur.lI")' challenges I [edued by) Tholtw I3mchofT ;and J<hi C;l.\.1J}O\o~ Dcscripoon:W.3 hll1lt't n,l Ce()'lteIO" n UfU'",",If)' Pft-U.201f. I Includes blbllog~phlC;tI referen ., and mdex. ldenufiers: L N 20150242231 I 0 978162bJ62t177 (lunk",,«.ill paper) 1 I ON 9781626162860 (pbk. ,Ik p.lJ'<') II 0 9781626162ll1U (ebook) ubjects: l H:JesulI:S. I)c:5uJb-Edu ucn. I .Jo~huuon. I GlobabZJtlon-Rellgiow.:lspe ($- thchc burch. Iassificarion: L 8X3702.3 .J47 2016 I DO 271 .53-<14:23 LC record available at htrp:/lkcn.loc.govI201 5024223 e This book is printed on acid-free paper meenng the requirement of the American National tandard for Permanence 111 Paper for Pnneed Library Materials. 16 15 98765432 First printing Printed in the United States of America Cover design by Pam Pease The cover image is a combination of rwo public domain images: a quasi-traditional version of the IHS emblem of the Jesuits by Moransk! and the inset map Grbis Terramm NO'I{l et Accuratissima Tabllia by Pierer Goos (17th century). -

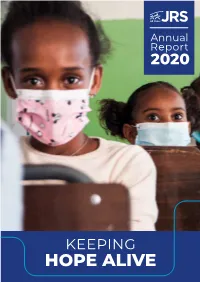

Hope Alive 2 Annual Report 2020 Annual Report 2020 1

ANNUAL REPORT 2020 _ 1 40 Years Annual Report 2020 KEEPING HOPE ALIVE 2 _ ANNUAL REPORT 2020 ANNUAL REPORT 2020 _ 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS This Annual Report is a testimony to those we serve and to your generosity. INTERNATIONAL DIRECTOR’S MESSAGE 2 Thank you - donors, partners, staff and THE LEGACY OF FR ARRUPE’S VISION: “We cannot volunteers - for your commitment to respond to today’s problems with yesterday’s solutions.” 4 leaving no one behind. Together, we are COVID-19 RESPONSE: Finding new ways to serve accompanying our vulnerable sisters our refugee sisters and brothers 6 and brothers towards a future of shared humanity and dignity. ACCOMPANYING FORCIBLY DISPLACED PEOPLE AROUND THE WORLD 10 YOUR IMPACT: You helped keep hope alive PUBLISHER with life-changing services 12 Thomas H. Smolich SJ EDUCATION & LIVELIHOODS: You helped provide EDITORIAL TEAM continuous educational and vocational opportunities 15 Elisa Barrios, Martina Bezzini, Valeria Di Francescantonio, Brette A. Jackson, RECONCILIATION: You helped rebuild right Madelaine Kuns, Francesca Segala. relationships during the pandemic 20 DESIGNER MENTAL HEALTH & PSYCHOSOCIAL SUPPORT: Mela | Immaginario Creativo You helped offer care and healing in times of lockdown 22 COVER PHOTO ADVOCACY: You helped ensure the most vulnerable Children attend informal education were not left behind 24 activities at the Refugee Community Centre in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. FINANCIAL SUMMARY 26 BACK PHOTO TAKE ACTION 28 A JRS kindergartener in Sharya, northern Iraq. PHOTO CREDITS Jesuit Refugee Service (JRS) School activities during COVID-19 in Kounoungou refugee camp, Chad. 2 _ ANNUAL REPORT 2020 ANNUAL REPORT 2020 _ 3 We are deeply grateful for Fr Sosa’s generous gift of €1,000,000 toward JRS’s INTERNATIONAL ongoing and future operations. -

Discussion Guide for “Renewed Commitment of the Jesuit Refugee Service” LETTER from the SUPERIOR GENERAL of the JESUITS, FR

Discussion Guide for “Renewed Commitment of the Jesuit Refugee Service” LETTER FROM THE SUPERIOR GENERAL OF THE JESUITS, FR. ARTURO SOSA, SJ In the spirit of Ignatian tradition, Jesuit Refugee Service/USA invites Jesuit institutions across the United States to take a moment of group discernment in response to the Superior General’s letter urging a renewed commitment to the Jesuit Refugee Service. As stated by Fr. Sosa, “This service to refugees requires a discernment that strives to be guided by the Spirit, and apostolic planning that makes effective use of human and all other available resources.” After reading Fr. Sosa’s letter, please set aside some time to reflect on the questions listed below and to discern what resources you have available to share in serving the needs of refugees and the forcibly displaced. *Updated numbers: Since the publication of Fr. Sosa's letter, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) released its annual report, which stated that, as of 2018, 70.8 million people had been forced from their homes, with 25.9 million of these people being refugees. About JRS Jesuit Refugee Service (JRS) is an international Catholic organization with a mission to accompany, serve, and advocate on behalf of refugees and other forcibly displaced persons. JRS undertakes services at national and regional levels with the support of an international office in Rome. JRS was found in 1980 by Pedro Arrupe, SJ as a work of the Society of Jesus. JRS currently serves more than 677,000 people in 56 countries. JRS/USA is a 501(c)3 organization based in Washington, DC that provides support – through funding, oversight, monitoring, and evaluation – to JRS projects and programming throughout the world. -

The Vatican's Twenty Points on Migration: a Primer

The Vatican’s Twenty Points on Migration ‧ Background ‧ Four Verbs - To Welcome - To Protect - To Promote - To Integrate Migrants-Refugees.va Resource: A Primer on the 20 Points https://justiceforimmigrants.org/caritas-share-the-journey-campaign/ The Compacts on Migration and on Refugees Global Compacts: The U.S. Response Giulia McPherson Director of Advocacy & Operations February 15, 2018 Jesuit Refugee Service • Jesuit Refugee Service (JRS) is an international Catholic organization serving refugees and other forcibly displaced people. • JRS was founded by Fr. Pedro Arrupe, S.J. in 1980, in direct response to the humanitarian crisis of the Vietnamese boat people. • Operating in 51 countries worldwide, JRS is a work of the Society of Jesus (the Jesuits) and meets the educational, health, and social needs of more than 750,000 refugees. Jesuit Refugee Service Jesuit Refugee Service U.S. Government Role • September 2016 – Adoption of the New York Declaration for Refugees and Migrants • September 2016 – Leaders’ Summit on Refugees • January 2017 – First Executive Order on Refugees • December 2017 - U.S. Government pulled out of Global Compact on Migration negotiations Civil Society Response • A vital part of JRS’s mission is to defend the rights of refugees and migrants throughout the world. • Initial feedback on Global Compact on Refugees Draft: • Lack of focus on refugee protection concerns • Must emphasize responsibility-sharing as a commitment, not an option • Lack of clear policy and legal action steps • Need for accountability and tracking mechanisms • Share feedback with UN Member States and via ongoing consultations • Goal: Final versions in September (Refugees) and December (Migration) What Can You Do? #Do1Thing • Experience - Host a Walk a Mile in My Shoes Refugee Simulation and provide your community with an opportunity to pause and learn about the experience, the frustrations, disappointments and hopes that refugees around the world face.