The Charlottetown Conference and Its Significance in Canadian History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Charlottetown

NOTES © 2009 maps.com QUEBEC Charlottetown MAINE NOVA SCOTIA PORT EXPLORER n New York City Atlantic Ocea Charlottetown PRINCE EDWARD ISLAND, CANADA GENERAL INFORMATION “…but if the path set over the Gulf of Saint Lawrence. The island is justly famous for its beautiful before her feet was to be narrow she knew that flowers rolling farmland, scattered forests and dramatic coastline. There are numer- of quiet happiness would bloom along it…God is in his ous beaches, wetlands and sand dunes along Prince Edward Island’s beautiful heaven, all is right with the world, whispered Anne soft- coast. The hidden coves were popular with rum-runners during the days of ly.” Anne of Green Gables - Lucy Maud Montgomery – prohibition in the United States. 1908 The people of Prince Edward Island are justly proud of the fact that it was For many people over the past century their first and per- in Charlottetown in 1864 that legislative delegates from the Canadian prov- haps only impression of Prince Edward Island came from inces gathered to discuss the possibility of uniting as a nation. This meeting, reading LM Montgomery’s now classic book. The story now known as the Charlottetown Conference, was instrumental in the eventual is about a young orphan girl who is adopted and raised adoption of Canada’s Articles of Confederation. by a farming couple on Prince Edward Island. Many of Canada became a nation on July 1, 1867…not before names such as Albion, young Anne’s adventures and observations are said to be Albionoria, Borealia, Efisga, Hochelaga, Laurentia, Mesopelagia, Tuponia, based on Ms. -

OECD/IMHE Project Self Evaluation Report: Atlantic Canada, Canada

OECD/IMHE Project Supporting the Contribution of Higher Education Institutions to Regional Development Self Evaluation Report: Atlantic Canada, Canada Wade Locke (Memorial University), Elizabeth Beale (Atlantic Provinces Economic Council), Robert Greenwood (Harris Centre, Memorial University), Cyril Farrell (Atlantic Provinces Community College Consortium), Stephen Tomblin (Memorial University), Pierre-Marcel Dejardins (Université de Moncton), Frank Strain (Mount Allison University), and Godfrey Baldacchino (University of Prince Edward Island) December 2006 (Revised March 2007) ii Acknowledgements This self-evaluation report addresses the contribution of higher education institutions (HEIs) to the development of the Atlantic region of Canada. This study was undertaken following the decision of a broad group of partners in Atlantic Canada to join the OECD/IMHE project “Supporting the Contribution of Higher Education Institutions to Regional Development”. Atlantic Canada was one of the last regions, and the only North American region, to enter into this project. It is also one of the largest groups of partners to participate in this OECD project, with engagement from the federal government; four provincial governments, all with separate responsibility for higher education; 17 publicly funded universities; all colleges in the region; and a range of other partners in economic development. As such, it must be appreciated that this report represents a major undertaking in a very short period of time. A research process was put in place to facilitate the completion of this self-evaluation report. The process was multifaceted and consultative in nature, drawing on current data, direct input from HEIs and the perspectives of a broad array of stakeholders across the region. An extensive effort was undertaken to ensure that input was received from all key stakeholders, through surveys completed by HEIs, one-on-one interviews conducted with government officials and focus groups conducted in each province which included a high level of private sector participation. -

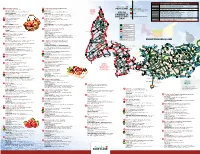

Fresh Products Directory

PEI FARMERS’ MARKET SCHEDULE 2018 East North WEDNESDAY Charlottetown Farmers’ Market (June-October) 9am – 2pm Point Cape 16 Royal Star Foods Ltd. Crystal Green Farms Kathy & Brian MacKay East Point e Certified Organic n 1A i 10am – 2pm e FRIDAY Cardigan Farmers’ Market (July-September) l 12 Products produced according to national organic e 175 Judes Point Road, Tignish C0B 2B0 2377 Route 112, Bedeque C0B 1C0 e n 1A i DRIVING d e standards. Farmers must pass yearly inspections a l (902) 882-2050 ext 362 (902) 314-3823 e M DISTANCES and maintain an audit trail of their products. 8:30am – 12pm - Bloomfield Farmers Market (Seasonal) ad a -l [email protected] | www.royalstarfoods.com [email protected] | www.crystalgreenfarms.com M e - 9am – 1pm a d Stanley Bridge Centre Farmers’ Market (Seasonal) l - Tignish to 182 16 - s e e SPRING, SUMMER, FALL YEAR ROUND FRESH U-Pick l d Î Summerside Farmers’ Market (Year Around) 9am – 1pm - Summerside s s e e 12 SATURDAY l SEAFOOD MARKET Lobster, Mussels, Oysters, Quahaugs, Bar Clams, MEAT, POULTRY & EGGS AND VEGETABLES Beets, Broccoli, 83km Charlottetown Farmers’ Market (Year Around) 9am – 2pm Î d o s PRODUCTS t e r s t Soft Shell Clams, Haddock, Value Added Products Cabbage, Carrots, Chicken, Eggs, Lamb, Potatoes, Spinach, Turnip 10am – 2pm e è Cardigan Farmers’ Market (June - October) r t Community Shared Agriculture e m lo Murray Harbour Farmers’ Market (Seasonal) 9am – 12pm m i DIRECTORY o k l i 4 14 k 3 Rennies U pick Alan Rennie Captain Cooke’s Seafood Inc. -

JOHN A. MACDONALD the Indispensable Politician

JOHN A. MACDONALD The Indispensable Politician by Alastair C.F. Gillespie With a Foreword by the Hon. Peter MacKay Board of Directors CHAIR Brian Flemming Rob Wildeboer International lawyer, writer, and policy advisor, Halifax Executive Chairman, Martinrea International Inc., Robert Fulford Vaughan Former Editor of Saturday Night magazine, columnist VICE CHAIR with the National Post, Ottawa Jacquelyn Thayer Scott Wayne Gudbranson Past President and Professor, CEO, Branham Group Inc., Ottawa Cape Breton University, Sydney Stanley Hartt MANAGING DIRECTOR Counsel, Norton Rose Fulbright LLP, Toronto Brian Lee Crowley, Ottawa Calvin Helin SECRETARY Aboriginal author and entrepreneur, Vancouver Lincoln Caylor Partner, Bennett Jones LLP, Toronto Peter John Nicholson Inaugural President, Council of Canadian Academies, TREASURER Annapolis Royal Martin MacKinnon CFO, Black Bull Resources Inc., Halifax Hon. Jim Peterson Former federal cabinet minister, Counsel at Fasken DIRECTORS Martineau, Toronto Pierre Casgrain Director and Corporate Secretary of Casgrain Maurice B. Tobin & Company Limited, Montreal The Tobin Foundation, Washington DC Erin Chutter Executive Chair, Global Energy Metals Corporation, Vancouver Research Advisory Board Laura Jones Janet Ajzenstat, Executive Vice-President of the Canadian Federation Professor Emeritus of Politics, McMaster University of Independent Business, Vancouver Brian Ferguson, Vaughn MacLellan Professor, Health Care Economics, University of Guelph DLA Piper (Canada) LLP, Toronto Jack Granatstein, Historian and former head of the Canadian War Museum Advisory Council Patrick James, Dornsife Dean’s Professor, University of Southern John Beck California President and CEO, Aecon Enterprises Inc., Toronto Rainer Knopff, Navjeet (Bob) Dhillon Professor Emeritus of Politics, University of Calgary President and CEO, Mainstreet Equity Corp., Calgary Larry Martin, Jim Dinning Prinicipal, Dr. -

Ballfields on PEI *This List Is Incomplete

Ballfields on PEI *This list is incomplete. If there is a field missing, or the information below is incorrect/incomplete, please email [email protected] Field Name Community Address Size Jerry McCormack Souris 203 Veteran’s Senior Memorial Field Memorial Highway Tubby Clinton Souris 99 Lea Crane 13U and below Memorial Field Boulevard Ronnie MacDonald St. Peter’s Bay 1968 Cardigan Road 13U and below Memorial Field Lions Field Morell 77 Red Head Road 13U and below Church Field Morell 100 Little Flower Senior Avenue MacDonald Field Peakes 2426 Mount Stewart Senior Road Mike Smith Tracadie Cross 129 Station Road 13U and below Memorial Field School Field Mount Stewart 120 South Main 11U and below Street Grand Tracadie Grand Tracadie 29 Harbour Road 13U and below Community Field Abegweit Ball Field Scotchfort Gluscap Drive 13U and below Clipper Field Cardigan 4364 Chapel Road Senior J.D. MacIntyre Cardigan 4364 Chapel Road 13U and below Memorial Field Kim Bujosevich Cardigan 4364 Chapel Road 13U and below Memorial Field John MacDonald Cardigan 4364 Chapel Road 13U and below Memorial Field Montague Regional Montague 274 Valleyfield Road 13U and below High School Field #1 Montague Regional Montague 274 Valleyfield Road 13U and below High School Field #2 MacSwain Field Georgetown 47 Kent Street Senior Jimmy Carroll Georgetown 29 Fitzroy Street 13U and below Memorial Field Belfast Field Belfast 3033 Garfield Road 13U and below Pete Milburn Murray River 1251 Gladstone Road 15U and below Memorial Field Mike Heron Fort Augustus 3801 Fort Augustus -

Ontario: the Centre of Confederation?

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository University of Calgary Press University of Calgary Press Open Access Books 2018-10 Reconsidering Confederation: Canada's Founding Debates, 1864-1999 University of Calgary Press Heidt, D. (Ed.). (2018). "Reconsidering Confederation: Canada's Founding Debates, 1864-1999". Calgary, AB: University of Calgary Press. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/108896 book https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives 4.0 International Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca RECONSIDERING CONFEDERATION: Canada’s Founding Debates, 1864–1999 Edited by Daniel Heidt ISBN 978-1-77385-016-0 THIS BOOK IS AN OPEN ACCESS E-BOOK. It is an electronic version of a book that can be purchased in physical form through any bookseller or on-line retailer, or from our distributors. Please support this open access publication by requesting that your university purchase a print copy of this book, or by purchasing a copy yourself. If you have any questions, please contact us at [email protected] Cover Art: The artwork on the cover of this book is not open access and falls under traditional copyright provisions; it cannot be reproduced in any way without written permission of the artists and their agents. The cover can be displayed as a complete cover image for the purposes of publicizing this work, but the artwork cannot be extracted from the context of the cover of this specific work without breaching the artist’s copyright. COPYRIGHT NOTICE: This open-access work is published under a Creative Commons licence. -

New Business Checklist

New Business Checklist Innovation PEI 94 Euston Street, PO Box 910, Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island, Canada C1A 7L9 Telephone: 902-368-6300 Facsimile: 902-368-6301 Toll-free: 1-800-563-3734 [email protected] www.princeedwardisland.ca 1. Initial Contacts For preliminary advice, the following organizations will be able to give you general information about how to start a business and direct you to other sources of information and assistance: • Innovation PEI • Finance PEI • Canada Business - PEI • Atlantic Canada Opportunities Agency (ACOA) • Regional Development Corporations • Rural Action Centres • Accountant / Lawyer / Banker A complete list of business development resource contacts is included with this checklist for your reference. 2. Form of Business Structure A business may be started as a sole proprietorship, partnership, corporation or cooperative, each with its own separate legal and tax characteristics. Seek legal advice when more than one owner is involved. Discuss the costs and benefits of incorporation, including limited liability, tax deferral and use of losses, with an accountant and a lawyer before proceeding. If you decide to incorporate, be sure to understand each of the following: • tax planning opportunities • drafting of buy / sell agreements • choice of federal or provincial incorporation • eligibility for employment insurance • directors’ liability / personal guarantees • annual costs and filing requirements 3. Initial Considerations The success or failure of a new business may be influenced by how well you research and consider the following: • personal commitment • competition • family support • utilities available • experience • patent, trademark, industrial design or copy- • financial resources for equity right protection • location (consider market, suppliers, • availability of qualified personnel competition) • quality of product or service • zoning, by-laws, restrictive covenants • costing • transportation facilities • markets • leasing versus owning of assets • management structure • security and fire protection 2 4. -

January 15, 2013 the City of Charlottetown's Task Force on Arts

January 15, 2013 The City of Charlottetown’s Task Force on Arts and Culture Presents a New Arts and Culture Strategy for the City 1 FOREWORD Dear Mayor Lee: The Task Force on Arts and Culture is pleased to present to you and your team at City Hall its findings and recommendations on a new arts and culture strategy for the City of Charlottetown. We greatly enjoyed the work of designing and refining these recommendations. On behalf of all task force members, I thank you for the opportunity to produce this report, and for appointing our group to the important mission of further cultivating a community of artistic and cultural production, vibrancy and innovation. The City of Charlottetown deserves credit for its pursuit and support of initiatives such as the 2011 Cultural Capital of Canada designation, and for recognizing the need to further develop the arts, culture and heritage sectors. Charlottetown can rightfully say it is taking a leadership role in engaging and nurturing Prince Edward Island’s arts and cultural community, and in promoting the importance of the arts in our provincial capital. Our task force has full confidence in the City’s ability to pursue these recommendations. Sincerely yours, Henk van Leeuwen Chair, City of Charlottetown Task Force on Arts and Culture cc: task force members Alan Buchanan, Jessie Inman, Ghislaine O’Hanley, Murray Murphy, Rob Oakie, Julia Sauve, Harmony Wagner, Josh Weale, Natalie Williams- Calhoun, and Darrin White 2 INTRODUCTION and BACKGROUND In October of 2011, Charlottetown Mayor Clifford Lee announced the creation of a Task Force to examine ways in which the City can deepen its support of arts and cultural activity in the provincial capital. -

GEORGE BROWN the Reformer

GEORGE BROWN The Reformer by Alastair C.F. Gillespie With a Foreword by the Hon. Preston Manning Board of Directors Richard Fadden Former National Security Advisor to the Prime Minister and former Deputy Minister of National Defence CHAIR Rob Wildeboer Brian Flemming Executive Chairman, Martinrea International Inc. International lawyer, writer, and policy advisor Robert Fulford VICE CHAIR Former Editor of Saturday Night magazine, columnist with Jacquelyn Thayer Scott the National Post Past President and Professor, Wayne Gudbranson Cape Breton University, Sydney CEO, Branham Group Inc., Ottawa MANAGING DIRECTOR Stanley Hartt Brian Lee Crowley Counsel, Norton Rose LLP SECRETARY Calvin Helin Lincoln Caylor International speaker, best-selling author, entrepreneur Partner, Bennett Jones LLP, Toronto and lawyer. TREASURER Peter John Nicholson Martin MacKinnon Former President, Canadian Council of Academies, Ottawa CFO, Black Bull Resources Inc., Halifax Hon. Jim Peterson Former federal cabinet minister, Counsel at Fasken DIRECTORS Martineau, Toronto Pierre Casgrain Maurice B. Tobin Director and Corporate Secretary of Casgrain the Tobin Foundation, Washington DC & Company Limited Erin Chutter President and CEO of Global Cobalt Corporation Research Advisory Board Laura Jones Janet Ajzenstat Executive Vice-President of the Canadian Federation Professor Emeritus of Politics, McMaster University of Independent Business (CFIB). Brian Ferguson Vaughn MacLellan Professor, Health Care Economics, University of Guelph DLA Piper (Canada) LLP Jack Granatstein Historian and former head of the Canadian War Museum Advisory Council Patrick James Professor, University of Southern California John Beck Rainer Knopff Chairman and CEO, Aecon Construction Ltd., Toronto Professor of Politics, University of Calgary Navjeet (Bob) Dhillon Larry Martin President and CEO, Mainstreet Equity Corp., Calgary Principal, Dr. -

Had Been Originally Under One Government—That of Nova Scotia. In

CHARLOTTETOWN CONFERENCE OF 1864 3 had been originally under one government—that of Nova Scotia. In 1769 Prince Edward Island was granted a government of its own, and, fifteen years later, New Brunswick became a separate province. From time to time thoughtful men dwelling by the sea had given expression to a feeling that while this system of subdivision might tend to convenience of administration by the Imperial authorities, the petty jealousies and narrowness of view which it engendered were not favourable to the growth and development of a country whose natural position and resources were such as to qualify it to play a leading part among the nations of the world. Some of the bolder spirits among them looked forward to a union which should embrace all British North America, although latterly the interminable post ponements, frequent political crises, and constant changes of policy in the Upper Provinces had caused the people of Nova Scotia, New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island to give up hope of coming to an arrangement with Canada. They resolved, therefore, to confine their efforts to bringing about an alliance among themselves, and to that end the legislatures of the Maritime Provinces authorized their respective governments to hold a joint conference for the purpose of discussing the expediency of a union of the three provinces of Nova Scotia, New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island under one government and legislature. This happened most opportunely for the newly-formed coalition government of Canada, which was just then casting about for the best means of opening negotiations with the other British colonies looking to union. -

'Region of the Mind,' Or Is It the Real Thing? Maritime Union

1er juillet 2017 – Times & Transcript ‘REGION OF THE MIND,’ OR IS IT THE REAL THING? MARITIME UNION DONALD SAVOIE COMMENTARY 1er juillet 2017 – Times & Transcript The Halifax skyline is seen from Dartmouth, N.S. in this 2009 file photo. Like it or not, writes Donald Savoie, the Maritime provinces face big changes ‘post Canada 150,’ and Maritime Union remains an option despite its controversies - including that the theoretical new province would likely result in one leading city. PHOTO: THE CANADIAN PRESS/FILE EDITOR’S NOTE: This is the final part in a four-part series by Université de Moncton public policy analyst Donald J. Savoie on the economic road ahead for New Brunswick and the Maritimes. The series carries a special emphasis on our region’s history and future in the context of Confederation, the 150th anniversary of which is celebrated today. I have often heard representatives of the region’s business community stressing the importance of greater cooperation between the three provincial governments. Some have told me that they favour Maritime political union, as I do. There are things that the business community could do to show the way and promote a Maritime perspective. The three provinces hold an annual ‘provincial’business hall of fame dinner to honour three business leaders. The business community would send a powerful message to the three provincial governments and to Maritimers if they were, instead, to hold one ‘Maritime’hall of fame event. The business community, not just government, has a responsibility for turning the region into something more than a ‘region of the mind.’ Regions of the mind have little in the way of policy instruments to promote economic development. -

The Crown and the Confederation

I THE CROWN AND THE CONFEDERATION. I . --... +-+-+~.. - T EE LETTE S TO THE HON. JOHN .ALEXANDER McDONALD, BY A BAOKWOODSMAN. Finis Coronat? ~tonfrtttI : JOHN LOVELL, PRINTER, ST. NICHOLAS STREET. 1864. ... The first and second of the followin g Letters are reprinted with a few verbal alterations from the Montreul Gaeette , the th ird nppears III print, for the first time, in th ese pages, .- THE CR,OvVNAND THE CON~1EDERATION. LETTER I. The fVriler introduces h.imself-State of opinion among his neighbors at JJiapleton- Conjusion of ideas as to the term Confederation-Monarchical Confederacies, ancient and modern-Lord Bacon's opinion that Monarchy is founded in the Natural Law - Monarchical elements in British Jimerican population-.J1nalysis thereof: The French Canadian. element " Old Country" element-the descendants of U. E. L oya.lists-The Con- federacv ought to embrace "the three estates." MAPLETON, C. E., Sept. sui, 1864. RESPECTED SIR,-In the ministerial explanations which you gave last June, in your place in Parliament, as to the occasion of that crisis, you were reported to have said that a settlement was to be sought for our constitutional perplexities, " in the well understood principles of Confederation." You will, I am assured from all that is reported of your character, excuse a plain man, wholly out of politics himself (except in so far as every subject of the Queen and spectator of events Inay be said to be interested), for addressing you a few words of commentary on your own text. In justice to what may seem crude or impractical in my style or opinions, I may be permitted to introduce myself as one who has formerly had a good deal of commerce with the world; which lay, howeve~, more with the past generation than the present; whose notions may therefore be open to the imputation of old-fash- 6 ioned, but who has not, if he knows his own heart , lost anything of his early hatred of all oppression, or his early enthusiasm for the happiness and good government of all mankind.