A Bench to Bedside Primer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Print This Article

International Surgery Journal Lew D et al. Int Surg J. 2021 May;8(5):1575-1578 http://www.ijsurgery.com pISSN 2349-3305 | eISSN 2349-2902 DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.18203/2349-2902.isj20211831 Case Report Acute gangrenous appendicitis and acute gangrenous cholecystitis in a pregnant patient, a difficult diagnosis: a case report David Lew, Jane Tian*, Martine A. Louis, Darshak Shah Department of Surgery, Flushing Hospital Medical Center, Flushing, New York, USA Received: 26 February 2021 Accepted: 02 April 2021 *Correspondence: Dr. Jane Tian, E-mail: [email protected] Copyright: © the author(s), publisher and licensee Medip Academy. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. ABSTRACT Abdominal pain is a common complaint in pregnancy, especially given the physiological and anatomical changes that occur as the pregnancy progresses. The diagnosis and treatment of common surgical pathologies can therefore be difficult and limited by the special considerations for the fetus. While uncommon in the general population, concurrent or subsequent disease processes should be considered in the pregnant patient. We present the case of a 36 year old, 13 weeks pregnant female who presented with both acute appendicitis and acute cholecystitis. Keywords: Appendicitis, Cholecystitis, Pregnancy, Pregnant INTRODUCTION population is rare.5 Here we report a case of concurrent appendicitis and cholecystitis in a pregnant woman. General surgeons are often called to evaluate patients with abdominal pain. The differential diagnosis list must CASE REPORT be expanded in pregnant woman and the approach to diagnosing and treating certain diseases must also be A 36 year old, 13 weeks pregnant female (G2P1001) adjusted to prevent harm to the fetus. -

Utility of the Digital Rectal Examination in the Emergency Department: a Review

The Journal of Emergency Medicine, Vol. 43, No. 6, pp. 1196–1204, 2012 Published by Elsevier Inc. Printed in the USA 0736-4679/$ - see front matter http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jemermed.2012.06.015 Clinical Reviews UTILITY OF THE DIGITAL RECTAL EXAMINATION IN THE EMERGENCY DEPARTMENT: A REVIEW Chad Kessler, MD, MHPE*† and Stephen J. Bauer, MD† *Department of Emergency Medicine, Jesse Brown VA Medical Center and †University of Illinois-Chicago College of Medicine, Chicago, Illinois Reprint Address: Chad Kessler, MD, MHPE, Department of Emergency Medicine, Jesse Brown Veterans Hospital, 820 S Damen Ave., M/C 111, Chicago, IL 60612 , Abstract—Background: The digital rectal examination abdominal pain and acute appendicitis. Stool obtained by (DRE) has been reflexively performed to evaluate common DRE doesn’t seem to increase the false-positive rate of chief complaints in the Emergency Department without FOBTs, and the DRE correlated moderately well with anal knowing its true utility in diagnosis. Objective: Medical lit- manometric measurements in determining anal sphincter erature databases were searched for the most relevant arti- tone. Published by Elsevier Inc. cles pertaining to: the utility of the DRE in evaluating abdominal pain and acute appendicitis, the false-positive , Keywords—digital rectal; utility; review; Emergency rate of fecal occult blood tests (FOBT) from stool obtained Department; evidence-based medicine by DRE or spontaneous passage, and the correlation be- tween DRE and anal manometry in determining anal tone. Discussion: Sixteen articles met our inclusion criteria; there INTRODUCTION were two for abdominal pain, five for appendicitis, six for anal tone, and three for fecal occult blood. -

ACUTE Yellow Atrophy Ofthe Liver Is a Rare Disease; Ac

ACUTE YELLOW ATROPHY OF THE LIVER AS A SEQUELA TO APPENDECTOMY.' BY MAX BALLIN, M.D., OF DETROIT, MICHIGAN. ACUTE yellow atrophy of the liver is a rare disease; ac- cording to Osler about 250 cases are on record. This affection is also called Icterus gravis, Fatal icterus, Pernicious jaundice, Acute diffuse hepatitis, Hepatic insufficiency, etc. Acute yellow atrophy of the liver is characterized by a more or less sudden onset of icterus increasing to the severest form, headaches. insomnia, violent delirium, spasms, and coma. There are often cutaneous and mucous hiemorrhages. The temperature is usually high and irregular. The pulse, first normal, later rapid; urine contains bile pigments, albumen, casts, and products of incomplete metabolism of albumen, leucin, and tyrosin, the pres- ence of which is considered pathognomonic. The affection ends mostly fatally, but there are recoveries on record. The findings of the post-mortem are: liver reduced in size; cut surface mot- tled yellow, sometimes with red spots (red atrophy), the paren- chyma softened and friable; microscopically the liver shows biliary infiltration, cells in all stages of degeneration. Further, we find parenchymatous nephritis, large spleen, degeneration of muscles, haemorrhages in mucous and serous membranes. The etiology of this affection is not quite clear. We find the same changes in phosphorus poisoning; many believe it to be of toxic origin, but others consider it to be of an infectious nature; and we have even findings of specific germs (Klebs, Tomkins), of streptococci (Nepveu), staphylococci (Bourdil- lier), and also the Bacillus coli is found (Mintz) in the affected organs. The disease seems to occur always secondary to some other ailment, and is observed mostly during pregnancy (about one-third of all cases, hence the predominance in women), after Read before the Wayne County Medical Society, January 5, I903. -

The Differences Between ICD-9 and ICD-10

Preparing for the ICD-10 Code Set: Fact Sheet 2 October 1, 2015 Compliance Date Get the Facts to be Compliant Alert: The new ICD-10 compliance date is October 1, 2015. The Differences Between ICD-9 and ICD-10 This is the second fact sheet in a series and is focused on the differences between the ICD-9 and ICD-10 code sets. Collectively, the fact sheets will provide information, guidance, and checklists to assist you with understanding what you need to do to implement the ICD-10 code set. The ICD-10 code sets are not a simple update of the ICD-9 code set. The ICD-10 code sets have fundamental changes in structure and concepts that make them very different from ICD-9. Because of these differences, it is important to develop a preliminary understanding of the changes from ICD-9 to ICD-10. This basic understanding of the differences will then identify more detailed training that will be needed to appropriately use the ICD-10 code sets. In addition, seeing the differences between the code sets will raise awareness of the complexities of converting to the ICD-10 codes. Overall Comparisons of ICD-9 to ICD-10 Issues today with the ICD-9 diagnosis and procedure code sets are addressed in ICD-10. One concern today with ICD-9 is the lack of specificity of the information conveyed in the codes. For example, if a patient is seen for treatment of a burn on the right arm, the ICD-9 diagnosis code does not distinguish that the burn is on the right arm. -

Appendectomy: Simple Appendicitis

Appendectomy: Simple Appendicitis Your child has had an appendectomy (ap pen DECK toe mee). This is the surgical removal of the appendix. The appendix is a small, narrow sac at the beginning of the large intestine (Picture 1). The appendix has no known function. What to Expect After Surgery . Your child will awaken in the Post Anesthesia Care Unit (PACU) near the surgery area. He or she may be in the PACU for 1 to 2 hours. After your child wakes up in the PACU, he or she will return to a hospital room or be Esophagus transferred to the Surgery Unit. Discharge will be directly from the Surgery Unit. Liver Stomach . Your child will have 3 to 4 small incision Large sites (see Helping Hand HH-I-283, Intestines Laparoscopic Surgery (colon) ). Small . Your child will receive fluids and pain intestines medicine through an intravenous line (IV). Rectum When your child can take liquids by mouth, pain medicine will also be given by mouth. Appendix . Your child will need to cough and deep-breathe often to help keep the lungs clear. He or she may use a plastic device called an incentive Picture 1 The appendix inside the body. spirometer to help with this. Your child will need to get up and walk soon after surgery. Walking will help "wake up" the bowels; it will also help with breathing and blood flow. Your child will be able to go home on the same day of the surgery if he or she is: o able to drink clear liquids like water, clear soft drinks, broth, and fruit punch o taking pain medicine by mouth and his or her pain is controlled, and o able to walk. -

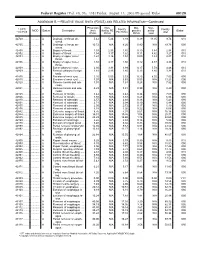

RELATIVE VALUE UNITS (RVUS) and RELATED INFORMATION—Continued

Federal Register / Vol. 68, No. 158 / Friday, August 15, 2003 / Proposed Rules 49129 ADDENDUM B.—RELATIVE VALUE UNITS (RVUS) AND RELATED INFORMATION—Continued Physician Non- Mal- Non- 1 CPT/ Facility Facility 2 MOD Status Description work facility PE practice acility Global HCPCS RVUs RVUs PE RVUs RVUs total total 42720 ....... ........... A Drainage of throat ab- 5.42 5.24 3.93 0.39 11.05 9.74 010 scess. 42725 ....... ........... A Drainage of throat ab- 10.72 N/A 8.26 0.80 N/A 19.78 090 scess. 42800 ....... ........... A Biopsy of throat ................ 1.39 2.35 1.45 0.10 3.84 2.94 010 42802 ....... ........... A Biopsy of throat ................ 1.54 3.17 1.62 0.11 4.82 3.27 010 42804 ....... ........... A Biopsy of upper nose/ 1.24 3.16 1.54 0.09 4.49 2.87 010 throat. 42806 ....... ........... A Biopsy of upper nose/ 1.58 3.17 1.66 0.12 4.87 3.36 010 throat. 42808 ....... ........... A Excise pharynx lesion ...... 2.30 3.31 1.99 0.17 5.78 4.46 010 42809 ....... ........... A Remove pharynx foreign 1.81 2.46 1.40 0.13 4.40 3.34 010 body. 42810 ....... ........... A Excision of neck cyst ........ 3.25 5.05 3.53 0.25 8.55 7.03 090 42815 ....... ........... A Excision of neck cyst ........ 7.07 N/A 5.63 0.53 N/A 13.23 090 42820 ....... ........... A Remove tonsils and ade- 3.91 N/A 3.63 0.28 N/A 7.82 090 noids. -

Incidental Drainage of a Periappendicular Abscess During Colonoscopy

UCTN – Unusual cases and technical notes E175 Incidental drainage of a periappendicular abscess during colonoscopy A 50-year-old man was referred to the of oral metronidazole and ciprofloxacin. A P. Figueiredo, V. Fernandes, J. Freitas outpatient colonoscopy clinic after a posi- computed tomography (CT) scan 1 week Department of Gastroenterology, tive fecal occult blood test during screen- after the procedure revealed no abnormal Hospital Garcia de Orta, Almada, Portugal ing for colorectal cancer. Colonoscopy, findings and the patient remained asymp- which was performed with the patient tomatic. sedated, revealed a 12-mm tumor covered Acute appendicitis is the most frequent References by normal, smooth mucosa at the site of acute abdominal emergency seen in de- 1 Oliak D, Yamini D, Udani VM et al. Can per- forated appendicitis be diagnosed preopera- the appendicular orifice. A biopsy was veloped countries. Its most common com- tively based on admission factors? J Gastro- taken, but this led to an immediate puru- plication is perforation and this may be intest Surg 2000; 4: 470–474 lent discharge occurring from the lesion followed by abscess formation [1]. Colo- 2 Ohtaka M, Asakawa A, Kashiwagi A et al. (●" Video 1). Therefore, a diagnosis of a noscopic diagnosis and treatment of a Pericecal appendiceal abscess with drainage periappendicular abscess was incidentally periappendicular abscess is rare [2]. In during colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc 1999; 49: 107–109 established. this case a periappendicular abscess was 3 Antevil J, Brown C. Percutaneous drainage After the patient had recovered from the incidentally discovered and drained dur- and interval appendectomy. In: Scott-Turner sedation, he was specifically questioned ing a colonoscopy. -

Immune Functions of the Vermiform Appendix

The Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism Volume 3 Print Reference: Pages 335-342 Article 30 1994 Immune Functions of the Vermiform Appendix Frank Maas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/icc_proceedings DigitalCommons@Cedarville provides a publication platform for fully open access journals, which means that all articles are available on the Internet to all users immediately upon publication. However, the opinions and sentiments expressed by the authors of articles published in our journals do not necessarily indicate the endorsement or reflect the views of DigitalCommons@Cedarville, the Centennial Library, or Cedarville University and its employees. The authors are solely responsible for the content of their work. Please address questions to [email protected]. Browse the contents of this volume of The Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism. Recommended Citation Maas, Frank (1994) "Immune Functions of the Vermiform Appendix," The Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism: Vol. 3 , Article 30. Available at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/icc_proceedings/vol3/iss1/30 IMMUNE FUNCTIONS OF THE VERMIFORM APPENDIX FRANK MAAS, M.S. 320 7TH STREET GERVAIS, OR 97026 KEYWORDS Mucosal immunology, gut-associated lymphoid tissues. immunocompetence, appendix (human and rabbit), appendectomy, neoplasm, vestigial organs. ABSTRACT The vermiform appendix Is purported to be the classic example of a vestigial organ, yet for nearly a century it has been known to be a specialized organ highly infiltrated with lymphoid tissue. This lymphoid tissue may help protect against local gut infections. As the vertebrate taxonomic scale increases, the lymphoid tissue of the large bowel tends to be concentrated In a specific region of the gut: the cecal apex or vermiform appendix. -

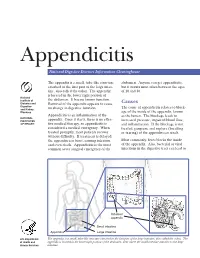

Appendicitis

Appendicitis National Digestive Diseases Information Clearinghouse The appendix is a small, tube-like structure abdomen. Anyone can get appendicitis, attached to the first part of the large intes- but it occurs most often between the ages tine, also called the colon. The appendix of 10 and 30. is located in the lower right portion of National Institute of the abdomen. It has no known function. Diabetes and Removal of the appendix appears to cause Causes Digestive The cause of appendicitis relates to block- and Kidney no change in digestive function. Diseases age of the inside of the appendix, known Appendicitis is an inflammation of the as the lumen. The blockage leads to NATIONAL INSTITUTES appendix. Once it starts, there is no effec- increased pressure, impaired blood flow, OF HEALTH tive medical therapy, so appendicitis is and inflammation. If the blockage is not considered a medical emergency. When treated, gangrene and rupture (breaking treated promptly, most patients recover or tearing) of the appendix can result. without difficulty. If treatment is delayed, the appendix can burst, causing infection Most commonly, feces blocks the inside and even death. Appendicitis is the most of the appendix. Also, bacterial or viral common acute surgical emergency of the infections in the digestive tract can lead to Inflamed appendix Small intestine Appendix Large intestine U.S. Department The appendix is a small, tube-like structure attached to the first part of the large intestine, also called the colon. The of Health and appendix is located in the lower right portion of the abdomen, near where the small intestine attaches to the large Human Services intestine. -

Case Report Perforated Acute Appendicitis Misdiagnosed As Colonic Perforation in Colon Cancer Patients After Colonoscopy: a Report of Two Cases and Literature Reviews

Int J Clin Exp Pathol 2017;10(6):7256-7260 www.ijcep.com /ISSN:1936-2625/IJCEP0050313 Case Report Perforated acute appendicitis misdiagnosed as colonic perforation in colon cancer patients after colonoscopy: a report of two cases and literature reviews Kaiyuan Zheng, Ji Wang, Wenhao Lv, Yongjia Yan, Zhicheng Zhao, Weidong Li, Weihua Fu Department of General Surgery, Tianjin Medical University General Hospital, Tianjin 300052, China Received January 23, 2017; Accepted May 9, 2017; Epub June 1, 2017; Published June 15, 2017 Abstract: Free gas in the abdominal cavity usually indicates that the perforation of the gastrointestinal tract from many factors including perforated ulcer, tumor perforation and severe infection, etc. But the pneumoperitoneum in perforated acute appendix secondary to the colonoscopy was rare relative. We reported two colon cancer patients with signs of abdominal free air after the operation of colonoscopy, considered the diagnosis of colon perforation at first, but eventually they were confirmed as perforated appendicitis. This report highlights that purulent perforated appendicitis should be considered especially for elderly patients with colon tumor presenting as signs of pneumo- peritoneum after the endoscopic operation. Keywords: Pneumoperitoneum, perforated appendicitis, colon cancer perforation, colonoscopy Introduction Acute perforated appendicitis is one of the common causes of acute abdomen and is Pneumoperitoneum is defined as free gas ap- needed emergency surgery. Its incidence was pears in the abdominal cavity, is usually caused higher in elderly population [6]. However, acute by the perforation of the alimentary tract sec- appendicitis following the operation of colonos- ondary to pathological or iatrogenic factors, but copy as a rare complication, with a consider- caused by purulent perforated appendix was ed incidence of 0.038%, and the appendix is rare relative. -

Crohn's Disease Manifesting As Acute Appendicitis: Case Report and Review of the Literature

Case Report World Journal of Surgery and Surgical Research Published: 20 Jan, 2020 Crohn's Disease Manifesting as Acute Appendicitis: Case Report and Review of the Literature Terrazas-Espitia Francisco1*, Molina-Dávila David1, Pérez-Benítez Omar2, Espinosa-Dorado Rodrigo2 and Zárate-Osorno Alejandra3 1Division of Digestive Surgery, Hospital Español, Mexico 2Department of General Surgery Resident, Hospital Español, Mexico 3Department of Pathology, Hospital Español, Mexico Abstract Crohn’s Disease (CD) is one of the two clinical presentations of Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) which involves the GI tract from the mouth to the anus, presenting a transmural pattern of inflammation. CD has been described as being a heterogenous disorder with multifactorial etiology. The diagnosis is based on anamnesis, physical examination, laboratory finding, imaging and endoscopic findings. There have been less than 200 cases of Crohn’s disease confined to the appendix since it was first described by Meyerding and Bertram in 1953. We present the case of a 24 year old male, who presented with acute onset, right lower quadrant pain, mimicking acute appendicitis with histopathological report of Crohn’s disease confined to the appendix. Introduction Crohn’s Disease (CD) is a chronic entity which clinical diagnosis represents one of the two main presentations of Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD), and it occurs throughout the gastrointestinal tract from the mouth to the anus, presenting a transmural pattern of inflammation of the gastrointestinal wall and non-caseating small granulomas. The exact origin of the disease remains OPEN ACCESS unknown, but it has been proposed as an interaction of genetic predisposition, environmental risk *Correspondence: factors and immune dysregulation of intestinal microbiota [1,2]. -

MANAGEMENT of ACUTE ABDOMINAL PAIN Patrick Mcgonagill, MD, FACS 4/7/21 DISCLOSURES

MANAGEMENT OF ACUTE ABDOMINAL PAIN Patrick McGonagill, MD, FACS 4/7/21 DISCLOSURES • I have no pertinent conflicts of interest to disclose OBJECTIVES • Define the pathophysiology of abdominal pain • Identify specific patterns of abdominal pain on history and physical examination that suggest common surgical problems • Explore indications for imaging and escalation of care ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS (1) HISTORICAL VIGNETTE (2) • “The general rule can be laid down that the majority of severe abdominal pains that ensue in patients who have been previously fairly well, and that last as long as six hours, are caused by conditions of surgical import.” ~Cope’s Early Diagnosis of the Acute Abdomen, 21st ed. BASIC PRINCIPLES OF THE DIAGNOSIS AND SURGICAL MANAGEMENT OF ABDOMINAL PAIN • Listen to your (and the patient’s) gut. A well honed “Spidey Sense” will get you far. • Management of intraabdominal surgical problems are time sensitive • Narcotics will not mask peritonitis • Urgent need for surgery often will depend on vitals and hemodynamics • If in doubt, reach out to your friendly neighborhood surgeon. Septic Pain Sepsis Death Shock PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF ABDOMINAL PAIN VISCERAL PAIN • Severe distension or strong contraction of intraabdominal structure • Poorly localized • Typically occurs in the midline of the abdomen • Seems to follow an embryological pattern • Foregut – epigastrium • Midgut – periumbilical • Hindgut – suprapubic/pelvic/lower back PARIETAL/SOMATIC PAIN • Caused by direct stimulation/irritation of parietal peritoneum • Leads to localized