The Aesthetics and Academics of Graphic Novels and Comics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Craig Thompson, Whose Latest Book Is, "Habibi," a 672-Page Tour De Force in the Genre

>> From the Library of Congress in Washington, DC. >> This is Jennifer Gavin at The Library of Congress. Late September will mark the 12th year that book lovers of all ages have gathered in Washington, DC to celebrate the written word of The Library of Congress National Book Festival. The festival, which is free and open to the public, will be 2 days this year, Saturday, September 22nd, and Sunday, September 23rd, 2012. The festival will take place between 9th and 14th Streets on ten National Mall, rain or shine. Hours will be from 10 a.m. to 5:30 p.m. Saturday, the 22nd, and from noon to 5:30 p.m. on Sunday the 23rd. For more details, visit www.loc.gov/bookfest. And now it is my pleasure to introduce graphic novelist Craig Thompson, whose latest book is, "Habibi," a 672-page tour de force in the genre. Mr. Thompson also is the author of the graphic novels, "Good-bye, Chunky Rice," "Blankets," and "Carnet de Voyage." Thank you so much for joining us. >> Craig Thompson: Thank you, Jennifer. It's a pleasure to be here. >> Could you tell us a bit about how you got into not just novel writing, but graphic novel writing? Are you an author who happens to draw beautifully, or an artist with a story to tell? >> Craig Thompson: Well, as a child I was really into comic books, and in a sort of natural adult progression fell out of love with the medium around high school, and was really obsessed with film and then animation, and was sort of mapping out possible career animation, and became disillusioned with that for a number of reasons. -

Emily Jones Independent Press Report Fall 2011

Emily Jones Independent Press Report Fall 2011 Table of Contents: Fact Sheet 3 Why I Chose Top Shelf 4 Interview with Chris Staros 5 Book Review: Blankets by Craig Thompson 12 2 Fact Sheet: Top Shelf Productions Web Address: www.topshelfcomix.com Founded: 1997 Founders: Brett Warnock & Chris Staros Editorial Office Production Office Chris Staros, Publisher Brett Warnock, Publisher Top Shelf Productions Top Shelf Productions PO Box 1282 PO Box 15125 Marietta GA 30061-1282 Portland OR 97293-5125 USA USA Distributed by: Diamond Book Distributors 1966 Greenspring Dr Ste 300 Timonium MD 21093 USA History: Top Shelf Productions was created in 1997 when friends Chris Staros and Brett Warnock decided to become publishing partners. Warnock had begun publishing an anthology titled Top Shelf in 1995. Staros had been working with cartoonists and had written an annual resource guide The Staros Report regarding the best comics in the industry. The two joined forces and shared a similar vision to advance comics and the graphic novel industry by promoting stories with powerful content meant to leave a lasting impression. Focus: Top Shelf publishes contemporary graphic novels and comics with compelling stories of literary quality from both emerging talent and known creators. They publish all-ages material including genre fiction, autobiographical and erotica. Recently they have launched two apps and begun to spread their production to digital copies as well. Activity: Around 15 to 20 books per year, around 40 titles including reprints. Submissions: Submissions can be sent via a URL link, or Xeroxed copies, sent with enough postage to be returned. -

List of American Comics Creators 1 List of American Comics Creators

List of American comics creators 1 List of American comics creators This is a list of American comics creators. Although comics have different formats, this list covers creators of comic books, graphic novels and comic strips, along with early innovators. The list presents authors with the United States as their country of origin, although they may have published or now be resident in other countries. For other countries, see List of comic creators. Comic strip creators • Adams, Scott, creator of Dilbert • Ahern, Gene, creator of Our Boarding House, Room and Board, The Squirrel Cage and The Nut Bros. • Andres, Charles, creator of CPU Wars • Berndt, Walter, creator of Smitty • Bishop, Wally, creator of Muggs and Skeeter • Byrnes, Gene, creator of Reg'lar Fellers • Caniff, Milton, creator of Terry and the Pirates and Steve Canyon • Capp, Al, creator of Li'l Abner • Crane, Roy, creator of Captain Easy and Wash Tubbs • Crespo, Jaime, creator of Life on the Edge of Hell • Davis, Jim, creator of Garfield • Defries, Graham Francis, co-creator of Queens Counsel • Fagan, Kevin, creator of Drabble • Falk, Lee, creator of The Phantom and Mandrake the Magician • Fincher, Charles, creator of The Illustrated Daily Scribble and Thadeus & Weez • Griffith, Bill, creator of Zippy • Groening, Matt, creator of Life in Hell • Guindon, Dick, creator of The Carp Chronicles and Guindon • Guisewite, Cathy, creator of Cathy • Hagy, Jessica, creator of Indexed • Hamlin, V. T., creator of Alley Oop • Herriman, George, creator of Krazy Kat • Hess, Sol, creator with -

Chris Ware's Jimmy Corrigan

Chris Ware’s Jimmy Corrigan Chris Ware’s Jimmy Corrigan : Honing the Hybridity of the Graphic Novel By DJ Dycus Chris Ware’s Jimmy Corrigan : Honing the Hybridity of the Graphic Novel, by DJ Dycus This book first published 2012 Cambridge Scholars Publishing 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2012 by DJ Dycus All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-3527-7, ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-3527-5 For my girls: T, A, O, and M TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures............................................................................................. ix CHAPTER ONE .............................................................................................. 1 INTRODUCTION TO COMICS The Fundamental Nature of this Thing Called Comics What’s in a Name? Broad Overview of Comics’ Historical Development Brief Survey of Recent Criticism Conclusion CHAPTER TWO ........................................................................................... 33 COMICS ’ PLACE WITHIN THE ARTISTIC LANDSCAPE Introduction Comics’ Relationship to Literature The Relationship of Comics to Film Comics’ Relationship to the Visual Arts Conclusion CHAPTER THREE ........................................................................................ 73 CHRIS WARE AND JIMMY CORRIGAN : AN INTRODUCTION Introduction Chris Ware’s Background and Beginnings in Comics Cartooning versus Drawing The Tone of Chris Ware’s Work Symbolism in Jimmy Corrigan Ware’s Use of Color Chris Ware’s Visual Design Chris Ware’s Use of the Past The Pacing of Ware’s Comics Conclusion viii Table of Contents CHAPTER FOUR ....................................................................................... -

Introduction to Comics Studies English 280· Summer 2018 · CRN 42457

Introduction to Comics Studies English 280· Summer 2018 · CRN 42457 Instructor: Dr. Andréa Gilroy · email: [email protected] · Office Hours: MWF 12-1:00 PM & by appointment All office hours conducted on Canvas Chat. You can message me personally for private conversation. Comics are suddenly everywhere. Sure, they’re in comic books and the funny pages, but now they’re on movie screens and TV screens and the computer screens, too. Millions of people attend conventions around the world dedicated to comics, many of them wearing comic-inspired costumes. If a costume is too much for you, you can find a comic book t-shirt at Target or the local mall wherever you live. But it’s not just pop culture stuff; graphic novels are in serious bookstores. Graphic novelists win major book awards and MacArthur “Genius” grants. Comics of all kinds are finding their way onto the syllabi of courses in colleges across the country. So, what’s the deal with comics? This course provides an introduction to the history and aesthetic traditions of Anglo-American comics, and to the academic discipline of Comics Studies. Together we will explore a wide spectrum of comic-art forms (especially the newspaper strip, the comic book, the graphic novel) and to a variety of modes and genres. We will also examine several examples of historical and contemporary comics scholarship. Objectives: This term, we will work together to… …better understand the literary and cultural conventions of the comics form. …explore the relevant cultural and historical information which will help situate texts within their cultural, political, and historical contexts. -

20090610 Board Packet Document #12-37

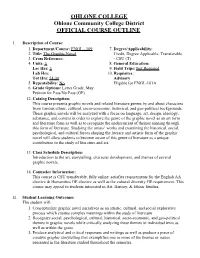

OHLONE COLLEGE Ohlone Community College District OFFICIAL COURSE OUTLINE I. Description of Course: 1. Department/Course: ENGL - 109 7. Degree/Applicability: 2. Title: The Graphic Novel Credit, Degree Applicable, Transferable 3. Cross Reference: - CSU (T) 4. Units: 3 8. General Education: Lec Hrs: 3 9. Field Trips: Not Required Lab Hrs: 10. Requisites: Tot Hrs: 54.00 Advisory 5. Repeatability: No Eligible for ENGL-101A 6. Grade Options: Letter Grade, May Petition for Pass/No Pass (GP) 12. Catalog Description: This course presents graphic novels and related literature genres by and about characters from various ethnic, cultural, socio-economic, historical, and geo-political backgrounds. These graphic novels will be analyzed with a focus on language, art, design, ideology, substance, and content in order to explore the genre of the graphic novel as an art form and literature form as well as to recognize the undercurrent of themes running through this form of literature. Studying the artists’ works and examining the historical, social, psychological, and cultural forces shaping the literary and artistic form of the graphic novel will allow students to become aware of this genre of literature as a unique contribution to the study of literature and art. 13. Class Schedule Description: Introduction to the art, storytelling, character development, and themes of several graphic novels. 14. Counselor Information: This course is CSU transferable, fully online, satisfies requirements for the English AA elective & Humanities GE elective as well as the cultural diversity GE requirement. This course may appeal to students interested in Art, History, & Ethnic Studies. II. Student Learning Outcomes The student will: 1. -

Comics and Graphic Novels Prerequisite(S): Third-Year Standing Or Permission of the Department

1 Carleton University Fall 2018 Department of English ENGL 3011A: Comics and Graphic Novels Prerequisite(s): third-year standing or permission of the department Wednesday and Friday / 2:35 p.m.-3:55pm Location: 280 University Center *confirm meeting place on Carleton Central prior to the first class* Instructor: B. Johnson Email: [email protected] Office: 1917 Dunton Tower Phone: (613) 520-2600 ext. 2331 Office Hours: Tuesdays 1:30 p.m.-3:00 p.m. Course Description This course has several broad goals, foremost among them is to guide students towards a fuller, richer, more pleasurable, more knowledgeable, and more intellectually stimulating experience of reading comics. To this end, the course will begin with a substantial introduction to the formal and technical dimensions of comics as a medium of expression. We will learn about how elements like the comic panel and the comic page function as systems of meaning and how visual and verbal systems of signification converge and interact within graphic space. We will develop our skills in visual literacy and examine some of the ways that comic narratives have shaped but also challenged the conventions of the medium across a very broad range of visual styles, genres, and aesthetic projects. Once we have developed some preliminary facility with the formal elements and technical language of comics, we will begin to pursue the secondary goals of the course in greater detail: (1) developing a sense of the material and cultural history of North American comics and (2) developing a sense of the emergent academic field of comic studies. -

Vol. 3 Issue 4 July 1998

Vol.Vol. 33 IssueIssue 44 July 1998 Adult Animation Late Nite With and Comics Space Ghost Anime Porn NYC: Underground Girl Comix Yellow Submarine Turns 30 Frank & Ollie on Pinocchio Reviews: Mulan, Bob & Margaret, Annecy, E3 TABLE OF CONTENTS JULY 1998 VOL.3 NO.4 4 Editor’s Notebook Is it all that upsetting? 5 Letters: [email protected] Dig This! SIGGRAPH is coming with a host of eye-opening films. Here’s a sneak peak. 6 ADULT ANIMATION Late Nite With Space Ghost 10 Who is behind this spandex-clad leader of late night? Heather Kenyon investigates with help from Car- toon Network’s Michael Lazzo, Senior Vice President, Programming and Production. The Beatles’Yellow Submarine Turns 30: John Coates and Norman Kauffman Look Back 15 On the 30th anniversary of The Beatles’ Yellow Submarine, Karl Cohen speaks with the two key TVC pro- duction figures behind the film. The Creators of The Beatles’Yellow Submarine.Where Are They Now? 21 Yellow Submarine was the start of a new era of animation. Robert R. Hieronimus, Ph.D. tells us where some of the creative staff went after they left Pepperland. The Mainstream Business of Adult Animation 25 Sean Maclennan Murch explains why animated shows targeted toward adults are becoming a more popular approach for some networks. The Anime “Porn” Market 1998 The misunderstood world of anime “porn” in the U.S. market is explored by anime expert Fred Patten. Animation Land:Adults Unwelcome 28 Cedric Littardi relates his experiences as he prepares to stand trial in France for his involvement with Ani- meLand, a magazine focused on animation for adults. -

Scb Distributors Fall 2015

SCB DISTRIBUTORS FALL 2015 SCB: TRULY INDEPENDENT SCB DISTRIBUTORS IS Blue Bird Press PROUD TO INTRODUCE Bullet Point Publishing Dark Dragon Books International Neighborhood Over and Above Creative Scratter & Pomace Tangent Books SCB: TRULY INDEPENDENT The cover image for this catalog is from page 105 of Al Parker: Illustrator, Innovator, published by Auad Publishing and found on page 17 of this catalog. Catalog layout by Dan Nolte, based on an original idea by Rama Crouch-Wong Unprepared To Die America’s Greatest Murder Ballads and the True Crime Stories That Inspired Them By Paul Slade “I thought I’d have a quick dip in and ended up reading it from start to end: compulsive stuff.” – Ian Anderson, Roots High concept folk culture tracing the history of 8 popular murder ballads, including Tom Dooley, Pretty Polly and Frankie And Johnny. Interviewees include Billy Bragg, The Handsome Family’s Renee Sparks, The Kingston Trio’s Bob Shane and Snakefarm’s Anna Domino, who share their insights into these iconic songs. These cheerfully vulgar murder ballads are tabloid newspapers set to music. Each has evolved to suit local place names and each mutates further still in the performances of Duke Ellington, James Brown, Bob Dylan, Dr. John, The Clash and Nick Cave, all of whom have re-interpreted Stagger Lee and RIVETING, UNUSUAL HISTORY other ballads. ■ with the stories of the real individuals whose short lives and brutal deaths are featured in each song Paul Slade is a London-based journalist who writes for the Independent, Guardian, Times, Sunday Telegraph, Sunday Times, Mojo, Time Out and more. -

Nominees Announced for 2017 Will Eisner Comic Industry Awards Sonny Liew’S the Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye Tops List with Six Nominations

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Jackie Estrada [email protected] Nominees Announced for 2017 Will Eisner Comic Industry Awards Sonny Liew’s The Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye Tops List with Six Nominations SAN DIEGO – Comic-Con International (Comic-Con) is proud to announce the nominations for the Will Eisner Comic Industry Awards 2017. The nominees were chosen by a blue-ribbon panel of judges. Once again, this year’s nominees reflect the wide range of material being published in comics and graphic novel form today, with over 120 titles from some 50 publishers and by creators from all over the world. Topping the nominations is Sonny Liew’s The Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye (Pantheon), originally published in Singapore. It is a history of Singapore from the 1950s to the present as told by a fictional cartoonist in a wide variety of styles reflecting the various time periods. It is nominated in 6 categories: Best Graphic Album–New, Best U.S. Edition of International Material–Asia, Best Writer/Artist, Best Coloring, Best Lettering, and Best Publication Design. Boasting 4 nominations are Image’s Saga and Kill or Be Killed. Saga is up for Best Continuing Series, Best Writer (Brian K. Vaughan), and Best Cover Artist and Best Coloring (Fiona Staples). Kill or Be Killed by Ed Brubaker and Sean Phillips is nominated for Best Continuing Series, Best Writer, Best Cover Artist, and Best Coloring (Elizabeth Breitweiser). Two titles have 3 nominations: Image’s Monstress by Marjorie Liu and Sana Takeda (Best Publication for Teens, Best Painter, Best Cover Artist) and Tom Gauld’s Mooncop (Best Graphic Album–New, Best Writer/Artist, Best Lettering), published by Drawn & Quarterly. -

Blankets Craig Thompson

Blankets Craig Thompson A cult classic and one of the bestselling graphic novels of all time. Sales points • First published in the US in 2003, Blankets is new to Faber • Craig Thompson is one of the most highly respected graphic novelists; he has received four Harvey Awards, three Eisner Awards and two Ignatz Awards Description 'Achingly beautiful. a first-love story so well remembered and honest that it reminds you what falling in love feels like.' - Time magazine Wrapped in the landscape of a blustery Wisconsin winter, Blankets explores the sibling rivalry of two brothers growing up in rural isolation, and the budding romance of two young lovers. A tale of security and discovery, of playfulness and tragedy, of a fall from grace and the origins of faith, Blankets is a profound and utterly beautiful work. About the Author Craig Thompson's previous graphic novels include Goodbye, Chunky Rice, Blankets, Carnet de Voyage, Habibi , an Observer Graphic Novel of the Month, a New York Times bestseller, and described by Neel Mukherjee as 'a landmark publication' - and most recently Space Dumplins. His work has received four Harvey Awards, three Eisner Awards and two Ignatz Awards. Price: $39.99 (NZ$45.00) ISBN: 9780571336029 Format: Paperback Dimensions: 228x178mm Extent: 592 pages Main Category: FX Sub Category: Illustrations: Previous Titles: Author now living: Faber Fiction The Map and the Clock: A Laureate's Choice of the Poetry of Britain and Ireland edited by Carol Ann Duffy and Gillian Clarke Now in paperback: a celebration of the most scintillating poems ever composed in Britain, chosen by Poet Laureate Carol Ann Duffy and Gillian Clarke, the National Poet of Wales. -

Moore Layout Original

Bibliography Within your dictionary, next to word “prolific” you’ll created with their respective co-creators/artists) printing of this issue was pulped by DC hierarchy find a photo of Alan Moore – who since his profes - because of a Marvel Co. feminine hygiene product ad. AMERICA’S BEST COMICS 64 PAGE GIANT – Tom sional writing debut in the late Seventies has written A few copies were saved from the company’s shred - Strong “Skull & Bones” – Art: H. Ramos & John hundreds of stories for a wide range of publications, der and are now costly collectibles) Totleben / “Jack B. Quick’s Amazing World of both in the United States and the UK, from child fare Science Part 1” – Art: Kevin Nowlan / Top Ten: THE LEAGUE OF EXTRAORDINARY GENTLEMEN like Star Wars to more adult publications such as “Deadfellas” – Art: Zander Cannon / “The FIRST (Volume One) #6 – “6: The Day of Be With Us” & Knave . We’ve organized the entries by publishers and First American” – Art: Sergio Aragonés / “The “Chapter 6: Allan and the Sundered Veil’s The listed every relevant work (comics, prose, articles, League Of Extraordinary Gentlemen Game” – Art: Awakening” – Art: Kevin O’Neill – 1999 artwork, reviews, etc...) written by the author accord - Kevin O’Neill / Splash Brannigan: “Specters from ingly. You’ll also see that I’ve made an emphasis on THE LEAGUE OF EXTRAORDINARY GENTLEMEN Projectors” – Art: Kyle Baker / Cobweb: “He Tied mentioning the title of all his penned stories because VOLUME 1 – Art: Kevin O’Neill – 2000 (Note: Me To a Buzzsaw (And It Felt Like a Kiss)” – Art: it is a pet peeve of mine when folks only remember Hardcover and softcover feature compilation of the Dame Darcy / “Jack B.