Commonalities of Success in the Ryder Cup and Super Bowl

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

City Manager Interviews Set Education Is Putting Its Selection Currently Sits in Seventh Place with of a New Director of Schools on 2,859 Points After Day 1

T U E S D A Y 162nd YEAR • NO. 21 MAY 24, 2016 CLEVELAND, TN 16 PAGES • 50¢ Sheriff accused of ‘conduct unbecoming’ By BRIAN GRAVES She said it was not her belief the sheriff Banner Staff Writer "of his own volition took [the BCSO Facebook] page down." Watson issues response Sheriff Eric Watson was accused of "I think that someone who may or may "conduct unbecoming" and being unre- not be in this room told him to, and I sponsive to a constituent's concerns dur- thank them," Williams said. to residents’ complaints ing Monday night's work session of the She said after the May 2014 Republican Bradley County Commission. primary when Watson won his office By BRIAN GRAVES During a meeting light on business, it because there was no Democratic opposi- Banner Staff Writer was the comments by two local residents tion, one of her daughters posted on her Bradley County Sheriff Eric Watson has responded to accusa- concerning the sheriff which took the Facebook page "a comment about him." tions made against him at Monday night’s County Commission spotlight. She did not give any specifics of the post- meeting after hearing a recording of that session Tuesday morn- Debbie Williams, who admitted to being ing. ing. a supporter of former Sheriff Jim Ruth, "It was true. The then-superintendent of In response to the comments made by Bradley County resident said she wanted to discuss the lawsuit schools and her principal called her in," Debbie Williams to commissioners during a work session, the against Watson and the county by the she said, noting her daughter had been Banner photo, BRIAN GRAVES sheriff said he appreciated “her honesty in expressing her sup- DEBBIE WILLIAMS addressed the Bradley American Atheists and a local "Jane Doe." told "He could sue you." port, past and present, for the former sheriff.” "What I'm in fear of is more lawsuits Williams said they researched U.S. -

Candidate Brief

Candidate Brief Brief for the position of Chief Executive Officer, PGA European Tour February 2015 Candidate Brief, February 2015 2 Chief Executive Officer, PGA European Tour Contents Welcome from the Chairman ................................................................................................................. 3 Summary......................................................................................................................................................... 4 The PGA European Tour........................................................................................................................... 5 Constitution and governance ............................................................................................................... 11 Role profile .................................................................................................................................................. 12 Selection criteria ....................................................................................................................................... 16 Principal challenges ................................................................................................................................. 17 Remuneration ............................................................................................................................................. 17 Search process ........................................................................................................................................... -

Sergio García

AAPPGGEE ASOCIACIÓN DE PROFESIONALES DE GOLF DE ESPAÑA Nº 29 SEPTIEMBRE 2005 DELARIVA Y DEL CORRAL VENCEN EN EL PLAY-OFF DEL CTO. DE DOBLES EL CTO. DE ESPAÑA DE LA APG, EL CTO. DE PROFESIONALES EN SANT CUGAT DE CLUB VUELVE A MONDARIZ PATROCINADORES MERCHANDISING APG APG Ribera del Duero Vehículos de alquiler oficial Agencia de viajes oficial Vino oficial Ropa oficial Aseguradora oficial Cigarro oficial Tarjeta de crédito oficial Telefonía móvil oficial Calcetín oficial Bola oficial 2º Campeonato de España de Profesionales de OFERTA DE TRABAJO Club APG DIRECTOR TÉCNICO DEL 20 AL 22 DE SEPTIEMBRE Los 130 participantes inscritos en esta segunda edición supone ESCUELA A.P.G. un gran éxito de participación y un paso más para consolidar un campeonato por el que la APG tiene una especial sensibilidad, dado que en él participan profesionales que habitualmente dedi- FUNCIONES: can su tiempo a impartir clases en los clubes de toda la geogra- - Diseñar y elaborar método de trabajo que se aplicará en las fía española, algunos de los cuáles han pasado muchos años futuras escuelas A.P.G. compitiendo en los Circuitos Europeos y encarnan parte de los - Creación de cursos paralelos (psicología, preparación física, nombres que han sido historia de este deporte. biomecánica, biodinámica, alimentación deportiva, etc.) El campeonato repartirá un mínimo de 28.000 euros en premios y - Responsable de la educación y formación de los profesores estará patrocinado por Agfa, Dirección Xeral de Deportes Xunta de de Golf A.P.G. que van a ir a las escuelas Galicia, Fundación Deporte Galego, Dirección Xeral de Turismo Xunta de Galicia, Patronato de Turismo Rias Baixas y Aguas de Mondariz REQUISITOS: - Categoría de Maestro con una antigüedad mínima de 5 años 20º Campeonato de SE OFRECE: - Contratación a tiempo parcial - Sueldo a negociar España de la APG Interesados enviar Currículum Vitae a la A.P.G. -

PLAYERS GUIDE — Shinnecock Hills Golf Club | Southampton, N.Y

. OP U.S EN SHINNECOCK HILLS TH 118TH U.S. OPEN PLAYERS GUIDE — Shinnecock Hills Golf Club | Southampton, N.Y. — June 14-17, 2018 conducted by the 2018 U.S. OPEN PLAYERS' GUIDE — 1 Exemption List SHOTA AKIYOSHI Here are the golfers who are currently exempt from qualifying for the 118th U.S. Open Championship, with their exemption categories Shota Akiyoshi is 183 in this week’s Official World Golf Ranking listed. Birth Date: July 22, 1990 Player Exemption Category Player Exemption Category Birthplace: Kumamoto, Japan Kiradech Aphibarnrat 13 Marc Leishman 12, 13 Age: 27 Ht.: 5’7 Wt.: 190 Daniel Berger 12, 13 Alexander Levy 13 Home: Kumamoto, Japan Rafael Cabrera Bello 13 Hao Tong Li 13 Patrick Cantlay 12, 13 Luke List 13 Turned Professional: 2009 Paul Casey 12, 13 Hideki Matsuyama 11, 12, 13 Japan Tour Victories: 1 -2018 Gateway to The Open Mizuno Kevin Chappell 12, 13 Graeme McDowell 1 Open. Jason Day 7, 8, 12, 13 Rory McIlroy 1, 6, 7, 13 Bryson DeChambeau 13 Phil Mickelson 6, 13 Player Notes: ELIGIBILITY: He shot 134 at Japan Memorial Golf Jason Dufner 7, 12, 13 Francesco Molinari 9, 13 Harry Ellis (a) 3 Trey Mullinax 11 Club in Hyogo Prefecture, Japan, to earn one of three spots. Ernie Els 15 Alex Noren 13 Shota Akiyoshi started playing golf at the age of 10 years old. Tony Finau 12, 13 Louis Oosthuizen 13 Turned professional in January, 2009. Ross Fisher 13 Matt Parziale (a) 2 Matthew Fitzpatrick 13 Pat Perez 12, 13 Just secured his first Japan Golf Tour win with a one-shot victory Tommy Fleetwood 11, 13 Kenny Perry 10 at the 2018 Gateway to The Open Mizuno Open. -

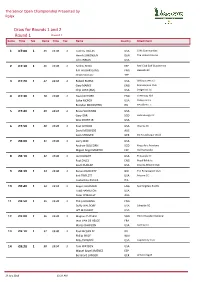

Draw for Rounds 1 and 2 Round 1 Round 2 Game Time Tee Game Time Tee Name Country Attachment

The Senior Open Championship Presented by Rolex Draw for Rounds 1 and 2 Round 1 Round 2 Game Time Tee Game Time Tee Name Country Attachment 1 07:00 1 25 11:30 1 Tommy TOLLES USA Cliffs Communities Henrik SIMONSEN DEN The Honors Course John INMAN USA 2 07:10 1 26 11:40 1 Andres ROSA ESP Real Club Golf Guadalmina B.R. HUGHES (AM) ENG Hesketh GC Chien Soon LU TPE 3 07:20 1 27 11:50 1 Robert BURNS USA Willow Creek GC Gary MARKS ENG Roehampton Club Chip LUTZ (AM) USA Ledgerock GC 4 07:30 1 28 12:00 1 David GILFORD ENG Greenway Hall Spike MCROY USA Valley Hill CC Brendan MCGOVERN IRL Headfort G.C 5 07:40 1 29 12:10 1 Bruce VAUGHAN USA Gary ORR SCO Helensburgh GC Wes SHORT JR USA 6 07:50 1 30 12:20 1 Paul GOYDOS USA Virginia CC David MCKENZIE AUS Sven STRÜVER GER GC Teutoburger Wald 7 08:00 1 31 12:30 1 Larry MIZE USA Andrew OLDCORN SCO Kings Acre Academy Miguel Angel MARTIN ESP Golf Santander 8 08:10 1 32 12:40 1 Joe DURANT USA Pensacola CC Paul EALES ENG Royal Birkdale Scott DUNLAP USA Atlanta Athletic Club 9 08:30 1 33 13:00 1 Ronan RAFFERTY NIR The Renaissance Club Kirk TRIPLETT USA Arizona CC Costantino ROCCA ITA 10 08:40 1 34 13:10 1 Roger CHAPMAN ENG Sportingclass Events Todd HAMILTON USA Peter O'MALLEY AUS 11 08:50 1 35 13:20 1 Philip GOLDING ENG Duffy WALDORF USA Lakeside GC Jeff MAGGERT USA 12 09:00 1 36 13:30 1 Magnus P ATLEVI SWE PGA of Sweden National Jean VAN DE VELDE FRA Marco DAWSON USA Suntree CC 13 09:10 1 37 13:40 1 Paul MCGINLEY IRL Phillip PRICE WAL Billy ANDRADE USA Capital City Club 14 09:20 1 38 13:50 1 Tom WATSON USA -

Rolex and Golf Information Sheet

ROLEX AND GOLF Perpetual Excellence For more than a century, Rolex’s quest for excellence through continuous improvement and innovation has underpinned all of the company’s activities – in its watchmaking and all its engagements. As part of Perpetual Excellence, Rolex seeks partnerships with individuals and organizations in the arts and in sport who set the highest standards of performance. Note Please note that the following is generic information in line with the “traditional” calendar. However, given the extraordinary circumstances that have impacted the world, the dates of some of these events are likely to change in 2021. ROLEX AND GOLF Rolex supports the most prestigious events, players and organizations in golf and encourages the development of the game worldwide. Its contribution to excellence in the sport is based on a rich heritage stretching back more than 50 years. Rolex champions both innovation and respect for the spirit of the ancient game. AT THE HEART OF THE GAME Rolex is a leading supporter of golf, with its universal commitment across the men’s and women’s game and from amateur through to senior ranks. The Swiss watch brand partners the principal professional tournaments and tours in golf, including four Majors in men’s golf that constitute the pinnacle of achievement for the world’s best players each year: • the Masters Tournament at Augusta National Golf Club (United States) in April; • the PGA Championship in May; • the U.S. Open in June; • The Open in the United Kingdom in July. This support extends to all five Majors in women’s golf. -

Case Study: Ryder Cup 2016

Hazeltine National Golf Club, MN, USA digiLED displays the greatest show on turf In conjunction with partners GoVision, digiLED provided 15 digiLED Toura6 screens at the 2016 Ryder Cup, held at Hazeltine National Golf Club, Minnesota – more displays than at any previous PGA Tour event in history. Along with Team USA’s historic success over a battling European side, digiLED surpassed the record for the most screens ever provided for a professional golf event – 15 displays were temporarily deployed across the Hazeltine National golf course complex to deliver action replay and updated scoring presentation for the sport’s premier team competition. digiLED Toura6 tiles provide high resolution displays and offer stunning clarity of image, perfect for use both indoors and outdoors as deployed by Hazeltine NGC on both the golf course and inside the media centre. The ultra-lightweight (25.55kg per sqm) digiLED Toura6 comprises solid black-faced panels. Fast-rig mechanics and a built-in ladder system ensure ease of installation and service access, too. Graham Burgess, digiLED CEO said: “It was a privilege to be a part of such a prestigious event that captivates millions of people on both sides of the pond. With 15 screens dotted about the course, it was a big factor in generating atmosphere and energy, as well as providing score information to the players and fans alike." CASE STUDY: AV RENTAL & TOURING www.digiLED.com [email protected] +44 (0) 207 381 7840 The Pixel Depot, Copse Farm, Moorhurst Lane, Beare Green, Surrey, RH5 4LJ . -

Three Day Golfing & Sporting Memorabilia Sale

Three Day Golfing & Sporting Memorabilia Sale - Day 3 Thursday 06 December 2012 11:00 Mullock's Specialist Auctioneers The Old Shippon Wall Under Heywood Church Stretton SY6 7DS Mullock's Specialist Auctioneers (Three Day Golfing & Sporting Memorabilia Sale - Day 3) Catalogue - Downloaded from UKAuctioneers.com Lot: 2001 Lot: 2011 Half set of matching Winton golf irons – to incl no.2,3, mashie Set of 5x Maxwell irons to incl a jigger, mashie, mashie n/k, and mashie niblick – all with grips. (4) niblick and a putter plus a Tom Watt driver with brass back Estimate: £40.00 - £60.00 weight, and a Grant spoon – all with grips (7) Estimate: £140.00 - £160.00 Lot: 2002 Set of 7x various left hand golf clubs to incl driver, spoon, 4x Lot: 2012 irons and putter – 6 with grips Good half set of 6x golf clubs – incl a lofted driver, mid iron, Estimate: £80.00 - £100.00 Forgan mashie, niblick etc – all with grip. Estimate: £80.00 - £100.00 Lot: 2003 Half set of golf clubs to incl a brassie, 4 irons incl James Watt Lot: 2013 niblick and Scottish Champion blade putter - all with grips (6) Good half set of 6x golf clubs – a very good large headed Estimate: £60.00 - £75.00 spoon, 4x various irons and Tom Stewart putter, -all with grips (6) Estimate: £80.00 - £100.00 Lot: 2004 Half set of golf clubs – to incl large head spoon, mid iron, mashie, mashie niblick, niblick and a brass blade putter – all Lot: 2014 with grips (6) Interesting half set of 6 golf clubs – a large headed Thompson Estimate: £80.00 - £100.00 St Andrews spoon, Walter Hagen 3 iron, mashie, mashie n/k, niblick and Tom Stewart straight blade putter – all with grips Estimate: £100.00 - £120.00 Lot: 2005 Set of 7x golf clubs to incl a Simpson driver, The Loftem baffie, 4x various irons and Harry Ross maker blade putter – all with Lot: 2015 grips Half set of 6x golf clubs – to incl a large brassie, mid iron. -

The Senior Open Championship Presented by Rolex First-Round

The Senior Open Championship presented by Rolex Old Course at St. Andrews | St. Andrews, Scotland | July 26-29, 2018 First-Round Notes Thursday, July 26, 2018 Course Setup: Par 72 / 7,216 yards (Front: 35.042, Back: 37.724, R1 total: 72.766) Weather: Mostly sunny with a high in the low 70s. Wind from the SE at 10-15 mph. Media Contact: Chris Richards (678-644-4258) Player To Par Scores T1. Kirk Triplett -7 32-33 – 65 T1. Thaworn Wiratchant -7 31-34 – 65 T3. Paul McGinley -6 31-35 – 66 T3. Stephen Ames -6 33-33 – 66 T5. Bernhard Langer -5 32-35 – 67 T5. Scott McCarron -5 32-35 – 67 T5. David Toms -5 31-36 – 67 Quick Links: Leaderboard Tee Times PGATOURmedia.com (transcripts and other resources available for download) Kirk Triplett, 32-33 – 65 (-7) Triplett returned a bogey-free 65 and is a first-round leader/co-leader for the third time on PGA TOUR Champions. This is his second 18-hole lead/co-lead in a major, as he led after opening with an 8-under 62 at the 2017 U.S. Senior Open; he went on to finish second behind Kenny Perry. Triplett is making his fourth start at The Senior Open and first since 2015. His best finish was T8 at Royal Porthcawl in 2014. He played The Open Championship twice, and he finished T60 (73-71-74-72) at St. Andrews in 2000. In April at the Bass Pro Shops Legends of Golf at Big Cedar Lodge, Triplett holed a bunker shot for birdie on the first playoff hole to secure the victory with partner Paul Broadhurst. -

April 16-18 2018 01

April 16-18 2018 01 Table of Contents Welcome to the eighth celebration of Create@State: A Symposium of Research, Scholarship Schedule . 2 & Creativity, showcasing the quality works of our students from across all of our university’s colleges and disciplines . This venue provides an opportunity for undergraduate and graduate Map . 3 students to present original work to stakeholders and the community in a professional Presentation Schedule . 7 setting . The theme for Create@State 2018 is focused around the STEAM initiative to highlight integration of STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Math) with Art + Design . We are Oral & Creative Presentations . 22 excited to welcome Edwin Faughn, our distinguished keynote, as he presents to campus Poster Presentations . 45 and the community the intersection of art, design and science . I am proud of the intellect, creativity and innovation taking place at Arkansas State University . This event is a testament to the rich cocurricular learning experiences that are provided by our outstanding faculty Student Research Ambassadors 2017-2018 mentors . I hope you will participate in as many of the events over the three days as possible . Ashley Schulz Brett Hale Olivia Smith Genevieve Quenum Anna Mears Parker Knapp Best regards, Nathan Baggett Kristian Watson Courtney Cox QianQian Yu Neha Verma Quy Van Cameron Duke Andrew Sustich, Ph .D . Associate Vice Chancellor for Research Student Research Advisory Committee 2017-2018 Katerina Hill . .Neil Griffin College of Business Hilary Schloemer . Neil Griffin College of Business Tina Teague . College of Agriculture, Engineering & Technology Zahid Hossain . College of Agriculture, Engineering & Technology Virginie Rolland . College of Sciences & Mathematics David Saarnio . -

The Burden of Glory: Competing for Non-Monetary Incentives in Rank

The Burden of Glory: Competing for Non-monetary Incentives in Rank-order Tournaments Suggested running head: “The Burden of Glory” RAJA KALI Department of Economics. Sam M. Walton College of Business. University of Arkansas Henry Angus Building, 2053. Fayetteville, AR 72701-1201 [email protected] DAVID PASTORIZA* (corresponding author) Department of International Business. HEC Montréal. Chemin de la Cote-Sainte-Catherine, 3000. Montréal, Canada. H3T 2AT [email protected] JEAN-FRANÇOIS PLANTE Department of Decision Sciences. HEC Montréal. Chemin de la Cote-Sainte-Catherine, 3000. Montréal, Canada. H3T 2AT [email protected] The Burden of Glory: Competing for Non-monetary Incentives in Rank-order Tournaments Abstract In an environment in which elite, highly-paid professionals compete for non-monetary rewards, we find evidence of underperformance. Our analysis suggests that choking under pressure from high-stakes non-monetary rewards is behind the underperformance. This implies that high stakes non-monetary rewards can create meaningful pressure on individuals and lead to worse performance, a distinct issue that has yet to be adequately examined. These findings come from an examination of the behavior of top US golfers competing to earn a place on the US Ryder Cup team via their performance in PGA Tour tournaments with differing allocations of Ryder Cup qualifying points. Keywords: Competition, non-monetary incentives, high stakes, choking, performance, risk-taking, intimidation The Burden of Glory: Competing for Non-monetary Incentives in Rank-order Tournaments Abstract: In an environment in which elite, highly-paid professionals compete for non- monetary rewards, we find evidence of underperformance. Our analysis suggests that choking under pressure from high-stakes non-monetary rewards is behind the underperformance. -

Pgasrs2.Chp:Corel VENTURA

Senior PGA Championship RecordBernhard Langer BERNHARD LANGER Year Place Score To Par 1st 2nd 3rd 4th Money 2008 2 288 +8 71 71 70 76 $216,000.00 ELIGIBILITY CODE: 3, 8, 10, 20 2009 T-17 284 +4 68 70 73 73 $24,000.00 Totals: Strokes Avg To Par 1st 2nd 3rd 4th Money ê Birth Date: Aug. 27, 1957 572 71.50 +12 69.5 70.5 71.5 74.5 $240,000.00 ê Birthplace: Anhausen, Germany êLanger has participated in two championships, playing eight rounds of golf. He has finished in the Top-3 one time, the Top-5 one time, the ê Age: 52 Ht.: 5’ 9" Wt.: 155 Top-10 one time, and the Top-25 two times, making two cuts. Rounds ê Home: Boca Raton, Fla. in 60s: one; Rounds under par: one; Rounds at par: two; Rounds over par: five. ê Turned Professional: 1972 êLowest Championship Score: 68 Highest Championship Score: 76 ê Joined PGA Tour: 1984 ê PGA Tour Playoff Record: 1-2 ê Joined Champions Tour: 2007 2010 Champions Tour RecordBernhard Langer ê Champions Tour Playoff Record: 2-0 Tournament Place To Par Score 1st 2nd 3rd Money ê Mitsubishi Elec. T-9 -12 204 68 68 68 $58,500.00 Joined PGA European Tour: 1976 ACE Group Classic T-4 -8 208 73 66 69 $86,400.00 PGA European Tour Playoff Record:8-6-2 Allianz Champ. Win -17 199 67 65 67 $255,000.00 Playoff: Beat John Cook with a eagle on first extra hole PGA Tour Victories: 3 - 1985 Sea Pines Heritage Classic, Masters, Toshiba Classic T-17 -6 207 70 72 65 $22,057.50 1993 Masters Cap Cana Champ.