Information to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EDWARD J. GAY and FAMILY PAPERS (Mss

EDWARD J. GAY AND FAMILY PAPERS (Mss. 1295) Inventory Louisiana and Lower Mississippi Valley Collections Special Collections, Hill Memorial Library Louisiana State University Libraries Baton Rouge, Louisiana State University Reformatted 2007-2008 By John Hansen and Caroline Richard Updated 2013 Jennifer Mitchell GAY (EDWARD J. AND FAMILY) PAPERS Mss. # 1295 1797-1938 SPECIAL COLLECTIONS, LSU LIBRARIES CONTENTS OF INVENTORY SUMMARY .................................................................................................................................... 3 BIOGRAPHICAL/HISTORICAL NOTE ...................................................................................... 4 SCOPE AND CONTENT NOTE ................................................................................................... 6 LIST OF SERIES ............................................................................................................................ 7 Series I., Correspondence and Other Papers, 1797-1938, undated ................................................. 8 Series II., Printed Items, 1837-1911, undated ............................................................................... 58 Series III., Photographs, 1874-1901, undated. .............................................................................. 59 Series IV. Manuscript Volumes, 1825-1919, undated. ................................................................ 60 CONTAINER LIST ..................................................................................................................... -

Alabama State Historic Preservation Plan

ALABAMA STATE The 2020 – 2025 Alabama State Historic HISTORIC Preservation Plan is being supported in part by the Historic Preservation Fund administered by the National Park Service, Department of the Interior. The views and conclusions contained PRESERVATION in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the opinions or policies of the U.S. Government. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute their PLAN endorsements by the U.S. Government. Table of Contents A. ACRONYMS ............................................................................................................................................................... 2 B. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................................... 2 Mission Statement: ............................................................................................................................................................. 3 Vision Statement: ................................................................................................................................................................ 3 1. PLAN DEVELOPMENT AND ACCOMPLISHMENTS ..................................................................................... 3 2. STATEWIDE PRESERVATION GOALS AND OBJECTIVES ....................................................................... 12 3. CULTURAL RESOURCES PRIORITIES AND ASSESSMENT ..................................................................... -

The Difficult Plantation Past: Operational and Leadership Mechanisms and Their Impact on Racialized Narratives at Tourist Plantations

THE DIFFICULT PLANTATION PAST: OPERATIONAL AND LEADERSHIP MECHANISMS AND THEIR IMPACT ON RACIALIZED NARRATIVES AT TOURIST PLANTATIONS by Jennifer Allison Harris A Dissertation SubmitteD in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Public History Middle Tennessee State University May 2019 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Kathryn Sikes, Chair Dr. Mary Hoffschwelle Dr. C. Brendan Martin Dr. Carroll Van West To F. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I cannot begin to express my thanks to my dissertation committee chairperson, Dr. Kathryn Sikes. Without her encouragement and advice this project would not have been possible. I would like to express my deepest appreciation to my dissertation committee members Drs. Mary Hoffschwelle, Carroll Van West, and Brendan Martin. My very deepest gratitude extends to Dr. Martin and the Public History Program for graciously and generously funding my research site visits. I’m deeply indebted to the National Science Foundation project research team, Drs. Derek H. Alderman, Perry L. Carter, Stephen P. Hanna, David Butler, and Amy E. Potter. However, I owe special thanks to Dr. Butler who introduced me to the project data and offered ongoing mentorship through my research and writing process. I would also like to extend my deepest gratitude to Dr. Kimberly Douglass for her continued professional sponsorship and friendship. The completion of my dissertation would not have been possible without the loving support and nurturing of Frederick Kristopher Koehn, whose patience cannot be underestimated. I must also thank my MTSU colleagues Drs. Bob Beatty and Ginna Foster Cannon for their supportive insights. My friend Dr. Jody Hankins was also incredibly helpful and reassuring throughout the last five years, and I owe additional gratitude to the “Low Brow CrowD,” for stress relief and weekend distractions. -

Laura Plantation Mute Victims of Katrina: Four Louisiana Landscapes at Risk

The Cultural Landscape Foundation VACHERIE , LOUISIANA Laura Plantation Mute Victims of Katrina: Four Louisiana Landscapes at Risk In 1805, Guillaume Duparc, a French veteran of the American Revolution, took possession of a 12,000-acre site just four miles downriver from Oak Alley Plantation in St. James Parish. With only seventeen West African slaves, he began to clear the land, build a home and grow sugarcane on the site of a Colapissa Indian village. This endeavor, like many others, led to a unique blending of European, African and Native American cultures that gave rise to the distinctive Creole culture that flourished in the region before Louisiana became part of the United States . Today, Laura Plantation offers a rare view of this non-Anglo-Saxon culture. Architectural styles, family traditions and the social/political life of the Creoles have been illuminated through extensive research and documentation. African folktales, personal memoirs and archival records have opened windows to Creole plantation life – a life that was tied directly to the soil with an agrarian-based economy, a taste for fine food and a constant battle to find comfort in a hot, damp environment. Laura Plantation stands today as a living legacy dedicated to the Creole culture. HISTORY Situated 54 miles above New Orleans on the west bank of the Mississippi River, the historic homestead of Laura Plantation spreads over a 14-acre site with a dozen buildings listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The main house along with Creole cottages, slave cabins and farm buildings rest on an elevated landmass of rich alluvial silt created by a geological fault. -

E. Heritage Health Index Participants

The Heritage Health Index Report E1 Appendix E—Heritage Health Index Participants* Alabama Morgan County Alabama Archives Air University Library National Voting Rights Museum Alabama Department of Archives and History Natural History Collections, University of South Alabama Supreme Court and State Law Library Alabama Alabama’s Constitution Village North Alabama Railroad Museum Aliceville Museum Inc. Palisades Park American Truck Historical Society Pelham Public Library Archaeological Resource Laboratory, Jacksonville Pond Spring–General Joseph Wheeler House State University Ruffner Mountain Nature Center Archaeology Laboratory, Auburn University Mont- South University Library gomery State Black Archives Research Center and Athens State University Library Museum Autauga-Prattville Public Library Troy State University Library Bay Minette Public Library Birmingham Botanical Society, Inc. Alaska Birmingham Public Library Alaska Division of Archives Bridgeport Public Library Alaska Historical Society Carrollton Public Library Alaska Native Language Center Center for Archaeological Studies, University of Alaska State Council on the Arts South Alabama Alaska State Museums Dauphin Island Sea Lab Estuarium Alutiiq Museum and Archaeological Repository Depot Museum, Inc. Anchorage Museum of History and Art Dismals Canyon Bethel Broadcasting, Inc. Earle A. Rainwater Memorial Library Copper Valley Historical Society Elton B. Stephens Library Elmendorf Air Force Base Museum Fendall Hall Herbarium, U.S. Department of Agriculture For- Freeman Cabin/Blountsville Historical Society est Service, Alaska Region Gaineswood Mansion Herbarium, University of Alaska Fairbanks Hale County Public Library Herbarium, University of Alaska Juneau Herbarium, Troy State University Historical Collections, Alaska State Library Herbarium, University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa Hoonah Cultural Center Historical Collections, Lister Hill Library of Katmai National Park and Preserve Health Sciences Kenai Peninsula College Library Huntington Botanical Garden Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park J. -

The Antebellum Houses of Hancock County, Georgia

PRESERVING EARLY SOUTHERN ARCHITECTURE: THE ANTEBELLUM HOUSES OF HANCOCK COUNTY, GEORGIA by CATHERINE DREWRY COMER (Under the Direction of Wayde Brown) ABSTRACT Antebellum houses are a highly significant and irreplaceable cultural resource; yet in many cases, various factors lead to their slow deterioration with little hope for a financially viable way to restore them. In Hancock County, Georgia, intensive cultivation of cotton beginning in the 1820s led to a strong plantation economy prior to the Civil War. In the twenty-first century, however, Hancock has been consistently ranked among the stateʼs poorest counties. Surveying known and undocumented antebellum homes to determine their current condition, occupancy, and use allows for a clearer understanding of the outlook for the antebellum houses of Hancock County. Each of the antebellum houses discussed in this thesis tells a unique part of Hancockʼs history, which in turn helps historians better understand a vanished era in southern culture. INDEX WORDS: Historic preservation; Log houses; Transitional architecture; Greek Revival architecture; Antebellum houses; Antebellum plantations; Hancock County; Georgia PRESERVING EARLY SOUTHERN ARCHITECTURE: THE ANTEBELLUM HOUSES OF HANCOCK COUNTY, GEORGIA By CATHERINE DREWRY COMER B.S., Southern Methodist University, 2009 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF HISTORIC PRESERVATION ATHENS, GEORGIA 2016 © 2016 Catherine Drewry Comer All Rights Reserved PRESERVING EARLY SOUTHERN ARCHITECTURE: THE ANTEBELLUM HOUSES OF HANCOCK COUNTY, GEORGIA by CATHERINE DREWRY COMER Major Professor: Wayde Brown Committee: Mark Reinberger Scott Messer Rick Joslyn Electronic Version Approved: Suzanne Barbour Dean of the Graduate School The University of Georgia May 2016 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I want to thank my family and friends for supporting me throughout graduate school. -

Gothic Revival Outbuildings of Antebellum Charleston, South Carolina Erin Marie Mcnicholl Clemson University

Clemson University TigerPrints Master of Science in Historic Preservation Terminal Non-thesis final projects Projects 5-2010 Gothic Revival Outbuildings of Antebellum Charleston, South Carolina Erin Marie McNicholl Clemson University Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/historic_pres Part of the Historic Preservation and Conservation Commons Recommended Citation McNicholl, Erin Marie, "Gothic Revival Outbuildings of Antebellum Charleston, South Carolina" (2010). Master of Science in Historic Preservation Terminal Projects. 4. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/historic_pres/4 This Terminal Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Non-thesis final projects at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master of Science in Historic Preservation Terminal Projects by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GOTHIC REVIVAL OUTBUILDNGS OF ANTEBELLUM CHARLESTON, SOUTH CAROLINA A Project Presented to the Graduate Schools of Clemson University/College of Charleston In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science Historic Preservation by Erin Marie McNicholl May 2010 Accepted by: Ashley Robbins Wilson, Committee Chair Ralph Muldrow Barry Stiefel, PhD ABSTRACT The Gothic Revival was a movement of picturesque architecture that is found all over the United States on buildings built in the first half of the nineteenth century. In Antebellum Charleston people tended to cling to the classical styles of architecture even when the rest of the nation and Europe were enthusiastically embracing the different picturesque styles, such as Gothic Revival and Italianate. In the United States the Gothic Revival style can be found adorning buildings of every use. -

Nottoway-Plantation-Resort-Brochure

Explore ... THE GRANDEUR & THE STORIES OF NOTTOWAY. Guided tours of the mansion Guided Mansion Tours are offered 7 days a week. Completed in 1859, Nottoway’s Self-guided tours of the grounds, museum & theater spectacular 53,000 square foot are also available daily. mansion was built by sugar- cane magnate John Hampden Randolph for his wife and their 11 children. Known for its stunning architectural design, elaborate interiors and innovative features, this majestic “White Castle” continues to captivate visitors from around the world. Experience the grandeur and unique charm that sets this plantation apart. Let our tour guides regale you with the fascinating stories and history of Nottoway, the grandest antebellum mansion in the South to survive the Civil War. www.nottoway.com Louisiana’s Premier Historical Resort Nottoway Plantation & Resort Room Reservations 31025 Hwy. 1 • White Castle, LA 70788 · Online at www.nottoway.com Ph: 866-527-6884 · 225-545-2730 · Or call 866-527-6884 (toll-free) Fax: 225-545-8632 or 225-545-2730 (local) www.nottoway.com Restaurant Reservations Facilities · Online at www.seatme.com · AAA Four Diamonds Award · National Register of Historic Places · 40 elegantly appointed accommodations ◦ 7 bed & breakfast-style rooms ◦ 28 deluxe rooms ◦ 3 corporate cottage suites ◦ 2 honeymoon suites · All non-smoking rooms · Handicap-accessible rooms · Mansion Restaurant & Bar/Lounge · Le Café · Fitness Center with lounge, TV, pool table · Business Center · Guided & self-guided tours · Museum & theater, historical cemetery · Gift shop · On-site salon: hair, nails, massage · Outdoor pool and cabana with hot tub · The Island Golf Club - 10 minutes away Location · Ample free parking Centrally located between Louisiana’s · Buses welcome · Special group rates 3 major metropolitan cities, New Orleans, Baton Rouge and Lafayette. -

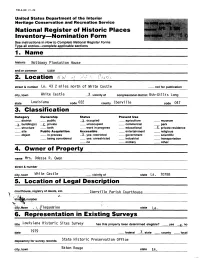

National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination

FHR-8-300 (11-78) United States Department of the Interior Heritage Conservation and Recreation Service National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries—complete applicable sections_______________ 1. Name__________________ historic Nottoway Plantation House________________ and/or common same 2. Location A/ v street & number La. 43 2 miles north of White Castle not for publication city,town White Castle ________JL vicinity of____congressional district 8th-Gi 11 i S Long state Louisiana code 022 county Iberville Code 047 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use district public X occupied agriculture museum X building(s) X private unoccupied commercial park structure both work in progress educational _ X_ private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment religious object in process X yes: restricted government scientific being considered yes: unrestricted industrial transportation no military other- 4. Owner of Property name Mrs. Odessa R. Owen street & number city,town whi te Castle vicinity of state La. 70788 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Iberville Parish Courthouse number \ sPlaquemine state La. 6. Representation in Existing Surveys tjtle Louisiana Historic Sites Survey has this property been determined elegible? no date 1979 federal X state __ county local depository for survey records state Historic Preservation Office city, town Baton Rouge state 7. Description Condition Check one Check one __ excellent __ deteriorated __ unaltered 0(_ original site __ ruins X altered __ moved date fair __ unexposed Describe the present and original (if known) physical appearance Nottoway plantation house is set approximately 200 feet behind the Mississippi River levee, two miles north of the town of White Castle. -

Representing Slavery at Oakland Plantation

REPRESENTING SLAVERY AT OAKLAND PLANTATION, A NATIONAL PARK SERVICE HISTORIC SITE IN CANE RIVER CREOLE NATIONAL HISTORICAL PARK, LOUISIANA by NELL ZIEHL (Under the Direction of Ian Firth) ABSTRACT This paper provides a framework for slavery interpretation at Oakland Plantation, a National Park Service site that is part of the Cane River Creole National Historical Park in Louisiana. The analysis discusses modes of interpretation; evaluation of primary source material, with an emphasis on historic structures, cultural landscapes, and archaeology; evaluations and recommendations for the use of secondary source material; and interpretive strategies that can be applied to any site dealing with the issue of slavery representation. The paper also includes a discussion of select themes and issues related to slavery interpretation, such as contemporary racism, class oppression, the plantation system in the Southeast, and the historiography of slavery scholarship. INDEX WORDS: Museum interpretation, Southern history, African-American history, Slavery, Historic preservation, Plantations, Louisiana history REPRESENTING SLAVERY AT OAKLAND PLANTATION, A NATIONAL PARK SERVICE HISTORIC SITE IN CANE RIVER CREOLE NATIONAL HISTORICAL PARK, LOUISIANA by NELL M. H. ZIEHL A.B., Bryn Mawr College, 1997 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF HISTORIC PRESERVATION ATHENS, GEORGIA 2003 © 2003 Nell Ziehl All Rights Reserved REPRESENTING SLAVERY AT OAKLAND PLANTATION, -

Whitfield Home, «Cfainswoodtt HABS Ho, W-2U Demopolis, Alabama H^° AL A

ALA Whitfield Home, «CFainswoodtt HABS Ho, W-2U Demopolis, Alabama h^° AL A • PHOTOGRAPHS WRITTEN HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE DATA District Ho- 16 Historic American Buildings survey E. Walter Burkhardt, District Officer Ala. Polytechnic Inst., Auburn, Ala. *~* n&QBxe AHBJUCAS* mzimmn amm trvtflsga of "Satnaswood* Dsmopolia* Alabama 1 y&t pl«tt. a /irst floor pita* 3 ..'' Second floor plm. asd third floor plan* 4 / Hoof plan. 5 '' Jtortb elevation, plan of north $&r£®&f detail of oast iron ura** 6 West elevation* ? South ^l©^atioa» details of c*>3ml©©» t@xra,e®. pla& at south tBismeis, & Lonfitudlml aactlozu 9 Fro&t tsl^wiicm and plan north portico, baluatrocte censics® i§ad e&pitnl det&iXa* 10 Elevation and plan of B&sirass room, 11 Slavatloa plsa aixd details of port© cosher*. 12 Xntexler elevation toward dl&i&g sw% details of wall Erleae, oitxa^eat OE architrave* sad oolissia capital, 13 Interior elev&tioa, stair $wXLs details of m%®Xm$$* 14 BefXe-cied piss of filing, detail of ros#tt®g aad besm^* 15 Elev&tioass a&d details of ballroom. 16 KUrfttions &3&I. detail® of di&itag roo»* 1? felevatioiia- m& details of library. *• 18 Full else dotaila of plaster friasee* X9 £lev*rticiw asd detail* of mgst@rj£ b^dro<Me 20 Bte&tions and datalla of ssd.str#8$ room* 21 Sievations of firspl&G&s* 22 &X%%TIQT ssusie p&¥illia&. 23 Elevation &8d pl&&$ of slaw ta&s®t §@t^ house aM mats ©satrap® getaway*• 24 tetaila of plaate»r work eeili&gs and cosmic^* 2% Petalls of plaster mr& sellings ssd corisieg* j HA6S _ ftt4 Page-^. -

Sightseeing Tours

NASHVILLE’S #1 SIGHTSEEING TOURS BOOK NOW April 2013 – March 2014 TENNESSEE TRUST YOUR NASHVILLE EXPERIENCE TO GRAY LINE No other tour company has surpassed Gray Line in giving visitors to Nashville the ultimate thrill in experiencing Music City. For nearly four decades, Gray Line’s commitment to safety, highly trained drivers, professional guides and wide variety of entertaining sightseeing tours have been at the forefront of the travel industry in Nashville and in points beyond. RIDE IN COMFORT Not only are our touring coaches comfortable, but they’re also approved by Tennessee’s governmental safety agency. Each coach also: • seats approximately 25 people • is equipped with air conditioning • is ADA compliant • includes a professional driver-guide BOOK NOW Find the perfect tours for you and your group, then reserve your space as soon as possible. Seats on all tours are limited and are first come, first served. There are three ways to book: • (800) 251- 1864 or (615) 883-5555 • GrayLineTN.com • Scan this code with the appropriate app to go to the Gray Line website to book. 2 BOOK NOW • GrayLineTN.com (800) 251-1864 or (615) 883-5555 19 HOMES OF THE STARS DURATION – approximately 3.5 hours DAILY DEPARTURES – 9:00 a.m. and 1:30 p.m. COACH PICK-UP – please be in hotel lobby 30 minutes before tour COST – Adults $45.00 • Children (ages 6 – 11) $22.50 See the homes of many of Nashville’s biggest stars, while driving through some of the city’s most scenic, upscale and secluded areas. You’ll quickly see why so many entertainers call Music City their home.