Arxiv:2104.14481V2 [Astro-Ph.CO] 11 Jul 2021 −1 −1 a Simple Heuristic Analytical Derivation for the BTFR of H0 = 75 ± 3.8Km S Mpc [33]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NP 2013.Docx

LISTE INTERNATIONALE DES NOMS PROTÉGÉS (également disponible sur notre Site Internet : www.IFHAonline.org) INTERNATIONAL LIST OF PROTECTED NAMES (also available on our Web site : www.IFHAonline.org) Fédération Internationale des Autorités Hippiques de Courses au Galop International Federation of Horseracing Authorities 15/04/13 46 place Abel Gance, 92100 Boulogne, France Tel : + 33 1 49 10 20 15 ; Fax : + 33 1 47 61 93 32 E-mail : [email protected] Internet : www.IFHAonline.org La liste des Noms Protégés comprend les noms : The list of Protected Names includes the names of : F Avant 1996, des chevaux qui ont une renommée F Prior 1996, the horses who are internationally internationale, soit comme principaux renowned, either as main stallions and reproducteurs ou comme champions en courses broodmares or as champions in racing (flat or (en plat et en obstacles), jump) F de 1996 à 2004, des gagnants des neuf grandes F from 1996 to 2004, the winners of the nine épreuves internationales suivantes : following international races : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil (Amérique du Sud/South America) Japan Cup, Melbourne Cup (Asie/Asia) Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Queen Elizabeth II Stakes (Europe/Europa) Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf (Amérique du Nord/North America) F à partir de 2005, des gagnants des onze grandes F since 2005, the winners of the eleven famous épreuves internationales suivantes : following international races : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil (Amérique du Sud/South America) Cox Plate (2005), Melbourne Cup (à partir de 2006 / from 2006 onwards), Dubai World Cup, Hong Kong Cup, Japan Cup (Asie/Asia) Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Irish Champion (Europe/Europa) Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf (Amérique du Nord/North America) F des principaux reproducteurs, inscrits à la F the main stallions and broodmares, registered demande du Comité International des Stud on request of the International Stud Book Books. -

Owners, Kentucky Derby (1875-2017)

OWNERS, KENTUCKY DERBY (1875-2017) Most Wins Owner Derby Span Sts. 1st 2nd 3rd Kentucky Derby Wins Calumet Farm 1935-2017 25 8 4 1 Whirlaway (1941), Pensive (’44), Citation (’48), Ponder (’49), Hill Gail (’52), Iron Liege (’57), Tim Tam (’58) & Forward Pass (’68) Col. E.R. Bradley 1920-1945 28 4 4 1 Behave Yourself (1921), Bubbling Over (’26), Burgoo King (’32) & Brokers Tip (’33) Belair Stud 1930-1955 8 3 1 0 Gallant Fox (1930), Omaha (’35) & Johnstown (’39) Bashford Manor Stable 1891-1912 11 2 2 1 Azra (1892) & Sir Huon (1906) Harry Payne Whitney 1915-1927 19 2 1 1 Regret (1915) & Whiskery (’27) Greentree Stable 1922-1981 19 2 2 1 Twenty Grand (1931) & Shut Out (’42) Mrs. John D. Hertz 1923-1943 3 2 0 0 Reigh Count (1928) & Count Fleet (’43) King Ranch 1941-1951 5 2 0 0 Assault (1946) & Middleground (’50) Darby Dan Farm 1963-1985 7 2 0 1 Chateaugay (1963) & Proud Clarion (’67) Meadow Stable 1950-1973 4 2 1 1 Riva Ridge (1972) & Secretariat (’73) Arthur B. Hancock III 1981-1999 6 2 2 0 Gato Del Sol (1982) & Sunday Silence (’89) William J. “Bill” Condren 1991-1995 4 2 0 0 Strike the Gold (1991) & Go for Gin (’94) Joseph M. “Joe” Cornacchia 1991-1996 3 2 0 0 Strike the Gold (1991) & Go for Gin (’94) Robert & Beverly Lewis 1995-2006 9 2 0 1 Silver Charm (1997) & Charismatic (’99) J. Paul Reddam 2003-2017 7 2 0 0 I’ll Have Another (2012) & Nyquist (’16) Most Starts Owner Derby Span Sts. -

1930S Greats Horses/Jockeys

1930s Greats Horses/Jockeys Year Horse Gender Age Year Jockeys Rating Year Jockeys Rating 1933 Cavalcade Colt 2 1933 Arcaro, E. 1 1939 Adams, J. 2 1933 Bazaar Filly 2 1933 Bellizzi, D. 1 1939 Arcaro, E. 2 1933 Mata Hari Filly 2 1933 Coucci, S. 1 1939 Dupuy, H. 1 1933 Brokers Tip Colt 3 1933 Fisher, H. 0 1939 Fallon, L. 0 1933 Head Play Colt 3 1933 Gilbert, J. 2 1939 James, B. 3 1933 War Glory Colt 3 1933 Horvath, K. 0 1939 Longden, J. 3 1933 Barn Swallow Filly 3 1933 Humphries, L. 1 1939 Meade, D. 3 1933 Gallant Sir Colt 4 1933 Jones, R. 2 1939 Neves, R. 1 1933 Equipoise Horse 5 1933 Longden, J. 1 1939 Peters, M. 1 1933 Tambour Mare 5 1933 Meade, D. 1 1939 Richards, H. 1 1934 Balladier Colt 2 1933 Mills, H. 1 1939 Robertson, A. 1 1934 Chance Sun Colt 2 1933 Pollard, J. 1 1939 Ryan, P. 1 1934 Nellie Flag Filly 2 1933 Porter, E. 2 1939 Seabo, G. 1 1934 Cavalcade Colt 3 1933 Robertson, A. 1 1939 Smith, F. A. 2 1934 Discovery Colt 3 1933 Saunders, W. 1 1939 Smith, G. 1 1934 Bazaar Filly 3 1933 Simmons, H. 1 1939 Stout, J. 1 1934 Mata Hari Filly 3 1933 Smith, J. 1 1939 Taylor, W. L. 1 1934 Advising Anna Filly 4 1933 Westrope, J. 4 1939 Wall, N. 1 1934 Faireno Horse 5 1933 Woolf, G. 1 1939 Westrope, J. 1 1934 Equipoise Horse 6 1933 Workman, R. -

BUTTERS FAMILY There Were 4 Brothers Who Attended

BUTTERS FAMILY There were 4 brothers who attended Framlingham between 1888 and 1905 and a couple of them were very prominent racehorse trainers. JOSEPH ARTHUR “FRANK” BUTTERS (1888-95) Frank Butters was Champion Trainer 8 times between 1927 and 1949. In addition to training the winners of 15 Classics in England he also trained Irish Derby winners Turkhan, Nathoo and Hindostan and Prix de L'Arc de Triomphe winner Migoli for the Aga Khan III. Frank Butters was born in Austria, where his father Joseph rode and trained, and became a successful trainer there himself. During the 1914-18 war he was nominally interned, then trained in Italy before being given a 4 year contract as private trainer to the 17th Earl of Derby at Stanley House, Newmarket, becoming leading trainer in his first year there, 1927. When Lord Derby withdrew from racing for economic reasons, Butters leased the Fitzroy Stables in Newmarket as a public trainer. Here he trained for Mr A W Gordon and, later, the Aga Khan III and the 5th Earl of Durham. He considered Bahram to be the best horse he ever trained. Important successes: 2000 Guineas 1000 Guineas Derby Bahram 1935 (T) Fair Isle 1930 (T) Bahram 1935 (T) Mahmoud 1936 (T) Oaks St Leger Other major race(s) Beam 1927 (T) Fairway 1928 (T) (featuring horses in this database) Toboggan 1928 (T) Firdaussi 1932 (T) Princess of Wales's Stakes Colorado 1927 (T) Udaipur 1932 (T) Bahram 1935 (T) Eclipse Stakes Colorado 1927 (T) Light Brocade 1934 (T) Turkhan 1940 (T) Eclipse Stakes Fairway 1928 (T) Steady Aim 1946 (T) Tehran 1944 (T) Champion Stakes Fairway 1928 (T) Masaka 1948 (T) Champion Stakes Fairway 1929 (T) Champion Stakes Umidwar 1934 (T) Jockey Club Stakes Umidwar 1934 (T) Dewhurst Stakes, Newmarket Bala Hissar 1935 (T) LTCOLONEL JAMES WAUGH BUTTERS OBE (1889-1904) Unlike Frank, he doesn’t appear to have been involved at all in horse racing. -

Annotated Bibliography of Utah Tar Sand Deposits

ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY OF UTAH TAR SAND DEPOSITS By J. Wallace Gwynn and Francis V. Hanson OPEN-FILE REPORT 503 Utah Geological Survey UTAH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY a division of Utah Department of Natural Resources 2007 updated in 2009 ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY OF UTAH TAR SAND DEPOSITS By J. Wallace Gwynn1 and Francis V. Hanson2 OPEN-FILE REPORT 503 UTAH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Utah Geological Survey a division of Utah Department of Natural Resources 2007 updated in 2009 1 Utah Geological Survey 2 University of Utah, Department of Chemical and Fuels Engineering STATE OF UTAH Gary R. Herbert, Governor DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES Michael Styler, Executive Director UTAH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Richard G. Allis, Director PUBLICATIONS contact Natural Resources Map/Bookstore 1594 W. North Temple Salt Lake City, UT 84116 telephone: 801-537-3320 toll-free: 1-888-UTAH MAP Web site: http://mapstore.utah.gov email: [email protected] THE UTAH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY contact 1594 W. North Temple, Suite 3110 Salt Lake City, UT 84116 telephone: 801-537-3300 fax: 801-537-3400 Web site: http://geology.utah.gov This publication was originally released in 2007. Additional references were added, and the publication was updated in 2009. This open-file report makes information available to the public that may not conform to UGS technical, editorial, or policy standards. Therefore it may be premature for an individual or group to take actions based on its contents. Although this product represents the work of professional scientists, the Utah Department of Natural Resources, Utah Geological Survey, makes no warranty, expressed or implied, regarding its suitability for a particular use. -

University Faculty 2007-2008 University of Kentucky Bulletin University Faculty

374 University Faculty 2007-2008 University of Kentucky Bulletin University Faculty COLLEGE OF AGRICULTURE K. Darrh Bullock, extension professor, Ph.D., Georgia, 1992 Walter R. Burris, extension professor, Ph.D., Kentucky, 1974 AND SCHOOL OF HUMAN ENVIRONMENTAL Austin H. Cantor, associate professor, Ph.D., Cornell, 1974 SCIENCES Richard D. Coffey, associate extension professor, Ph.D., Kentucky, 1994 Robert J. Coleman, associate extension professor, Ph.D., Alberta, 1998 M. Scott Smith, dean Nancy M. Cox, professor, North Carolina State, 1982 William L. Crist, extension professor emeritus, Ph.D., Ohio State, 1970 AGRICULTURAL COMMUNICATIONS Gary L. Cromwell, professor, Ph.D., Purdue, 1967 Carla G. Craycraft, director Karl A. Dawson, adjunct professor, Ph.D., Iowa State, 1979 Ray H. Dutt, professor emeritus, Ph.D., Wisconsin, 1948 Carla G. Craycraft, extension professor, Ph.D., Oklahoma State, 1981 Lee A. Edgerton, associate professor, Ph.D., Purdue, 1970 Joe B. Williams, assistant extension professor emeritus, Ed.D., Kentucky, 1971 Donald G. Ely, professor, Ph.D., Kentucky, 1966 Craig H. Wood, extension professor, Ph.D., New Mexico State, 1985 David L. Harmon, professor, Ph.D., Nebraska, 1983 Robert J. Harmon, professor, Ph.D., Guelph, Ontario, 1977 AGRICULTURAL ECONOMICS Virgil W. Hays, professor emeritus, Ph.D., Iowa State, 1957 Lynn W. Robbins, chair George Heersche, Jr., extension professor, Ph.D., Kansas State, 1975 Robert Lee Beck, professor emeritus, Ph.D., Michigan State, 1963 Roger W. Hemken, professor emeritus, Ph.D., Cornell, 1957 Fred J. Benson, extension professor emeritus, Ph.D., Missouri, 1972 Bernhard Hennig, professor, Ph.D., Iowa State, 1982 Barry Wright Bobst, associate professor emeritus, Ph.D., Washington State, 1966 Clair L. -

Competitive Bidding As Book 3 Opens at Keeneland

MONDAY, SEPTEMBER 16, 2019 COMPETITIVE BIDDING CLEMENT ‘INVADER’ PUNCHES BREEDERS’ CUP TICKET WITH SUMMER SCORE AS BOOK 3 OPENS Decorated Invader (Declaration of War), bet hard throughout, backed up his support and overcame a slow pace to capture the AT KEENELAND GI Summer S. Sunday at Woodbine, a “Win and You’re In” race for the GI Breeders’ Cup Juvenile Turf. Showing a strong late kick to be second debuting July 13 at Saratoga, the $200,000 Keeneland September grad won geared down there next out Aug. 10 and was crushed down to even- money from a 9-2 morning line early in the wagering here before drifting up to fractional second favoritism by post. Away a step slowly, the West Point Thoroughbreds colorbearer tugged his way up a few spots into seventh as huge longshot Cadet Connelly (Grey Swallow {Ire}) went on with it through pedestrian splits of :24.26 and :48.43 over yielding turf. Cont. p9 IN TDN EUROPE TODAY PINATUBO ELECTRIC IN THE NATIONAL Session-topping Hip 1385 in the ring | Keeneland Godolphin’s Pinatubo (Ire) (Shamardal) justified all the hype with a nine-length romp in The Curragh’s G1 National S. Click or tap here to go straight to TDN Europe. by Jessica Martini LEXINGTON, KY - The Keeneland September Yearling Sale’s Book 3 section opened with a day of competitive bidding Sunday in Lexington as 256 yearlings changed hands for a total of $30,025,000. The sixth session average was $117,285 and the median was $85,000. Of the 366 horses offered, 110 failed to reach their reserves for a buy-back rate of 30.05%. -

Depositional Environments and Sequence Stratigraphy of the Bahram Formation (Middleelate Devonian) in North of Kerman, South-Central Iran

Geoscience Frontiers 7 (2016) 821e834 HOSTED BY Contents lists available at ScienceDirect China University of Geosciences (Beijing) Geoscience Frontiers journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/gsf Research paper Depositional environments and sequence stratigraphy of the Bahram Formation (middleelate Devonian) in north of Kerman, south-central Iran Afshin Hashmie*, Ali Rostamnejad, Fariba Nikbakht, Mansour Ghorbanie, Peyman Rezaie, Hossien Gholamalian Department of Geology, Faculty of Sciences, University of Hormozgan, Bandarabbas, Iran article info abstract Article history: This study is focused on sedimentary environments, facies distribution, and sequence stratigraphy. The Received 7 October 2014 facies and sequence stratigraphic analyses of the Bahram Formation (middleelate Devonian) in south- Received in revised form central Iran are based on two measured stratigraphic sections in the southern Tabas block. The Bah- 24 June 2015 ram Formation overlies red sandstones Padeha Formation in sections Hutk and Sardar and is overlain by Accepted 8 July 2015 Carboniferous carbonate deposits of Hutk Formation paraconformably, with a thickness of 354 and Available online 6 August 2015 386 m respectively. Mixed siliciclastic and carbonate sediments are present in this succession. The field observations and laboratory studies were used to identify 14 micro/petrofacies, which can be grouped Keywords: fl Bahram Formation into 5 depositional environments: shore, tidal at, lagoon, shoal and shallow open marine. A mixed Devonian carbonate-detrital shallow shelf is suggested for the depositional environment of the Bahram Formation Facies analysis which deepens to the east (Sardar section) and thins in southern locations (Hutk section). Three 3rd- Mixed carbonate-detrital shallow-shelf order cyclic siliciclastic and carbonate sequences in the Bahram Formation and one sequence shared with Sequence stratigraphy the overlying joint with Hutk Formation are identified, on the basis of shallowing upward patterns in the Tabas block micro/pertofacies. -

Pedigree Insights

Andrew Caulfield, October 17, 2006–Teofilo (Ire) P EDIGREE INSIGHTS The enormity of the task ahead of Teofilo mustn=t be under-estimated, as only two colts have managed to BY ANDREW CAULFIELD win even two legs of the Triple Crown since Nijinsky (Reference Point added the St Leger to his Derby DARLEY DEWHURST S.-G1, ,250,000, Newmarket, success in 1987, while Nashwan took the 2000 10-14, 2yo, c/f, 7fT, 1:26.12, gd/sf. Guineas and Derby two years later). The Triple Crown 1--TEOFILO (IRE), 127, c, 2, by Galileo (Ire) remains an exciting possibility, though, and Teofilo=s 1st Dam: Speirbhean (Ire) (SW-Ire), by Danehill record suggests that he could develop into that 2nd Dam: Saviour, by Majestic Light one-in-a-million colt blessed with the necessary 3rd Dam: Victoria Queen, by Victoria Park brilliance, versatility and toughness. Like Nijinsky, his O-Mrs J Bolger; B/T-J Bolger; J-K Manning; ,141,950. juvenile record stands at five wins from five starts and Lifetime Record: G1SW-Ire, 5-5-0-0, ,349,515. both colts gained their fifth success in the G1 Dewhurst S. However, the signs are that Jim Bolger, who also Click for the Racing Post chart or the free brisnet.com bred Teofilo, isn=t looking too far ahead, as he is now catalogue-style pedigree. considering sending his star colt to France for the Criterium International on October 29. If American racing thinks it has been hard done by, Nijinsky was a member of the second crop by with only three Triple Crown winners since Citation in Northern Dancer, a winner of the first two legs of the 1948 and none since Affirmed in 1978, spare a thought Triple Crown, whereas Teofilo comes from the second for the British fans. -

Chef-De-Race List

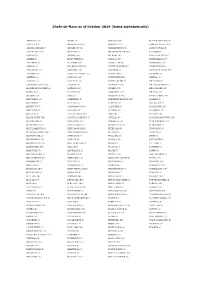

Chefs-de-Race as of October 2019 (listed alphabetically) ABERNANT (B) DJEBEL (I) MONSUN (C/S) RUN THE GANTLET (P) ACK ACK (I/C) DONATELLO II (P) MONTJEU (C/S) SADLER'S WELLS (C/S) ADMIRAL DRAKE (P) DOUBLE JAY (B) MOSSBOROUGH (C) SARDANAPALE (P) ALCANTARA II (P) DR. FAGER (I) MR. PROSPECTOR (B/C) SEA-BIRD (S) ALIBHAI (C) DUBAWI (I/S) MY BABU (B) SEATTLE SLEW (B/C) ALIZIER (P) EIGHT THIRTY (I) NASHUA (I/C) SECRETARIAT (I/C) ALYCIDON (P) EL PRADO (B/I) NASRULLAH (B) SHAMARDAL (I/C) ALYDAR (C) ELA-MANA-MOU (P) NATIVE DANCER (I/C) SHARPEN UP (B/C) APALACHEE (B) EQUIPOISE (I/C) NAVARRO (C) SHIRLEY HEIGHTS (C/P) A.P. INDY (I/C) EXCLUSIVE NATIVE (C) NEARCO (B/C) SICAMBRE (C) ASTERUS (S) FAIR PLAY (S/P) NEVER BEND (B/I) SIDERAL (C) AUREOLE (C) FAIR TRIAL (B) NEVER SAY DIE (C) SIR COSMO (B) AWESOME AGAIN (I/C) FAIRWAY (B) NIJINSKY II (C/S) SIR GALLAHAD III (C) BACHELOR’S DOUBLE (S) FAPPIANO (I/C) NINISKI (C/P) SIR GAYLORD (I/C) BAHRAM (C) FASLIYEV (B) NODOUBLE (C/P) SIR IVOR (I/C) BALDSKI (B/I) FORLI (C) NOHOLME II (B/C) SMART STRIKE (I/C) BALLYMOSS (S) FOXBRIDGE (P) NORTHERN DANCER (B/C) SOLARIO (P) BAYARDO (P) FULL SAIL (I) NUREYEV (C) SON-IN-LAW (P) BEN BRUSH (I) GAINSBOROUGH (C) OLEANDER (S) SPEAK JOHN (B/I) BEST TURN (C) GALILEO (C/S) OLYMPIA (B) SPEARMINT (P) BIG GAME (I) GALLANT MAN (B/I) ORBY (B) SPY SONG (B) BLACK TONEY (B/I) GIANT'S CAUSEWAY (C) ORTELLO (P) STAGE DOOR JOHNNY (S/P) BLANDFORD (C) GONE WEST (I/C) PANORAMA (B) STAR KINGDOM (I/C) BLENHEIM II (C/S) GRAUSTARK (C/S) PERSIAN GULF (C) STAR SHOOT (I) BLUE LARKSPUR (C) GREY DAWN II (B/I) PETER PAN (B) SUNNY BOY (P) BLUSHING GROOM (B/C) GREY SOVEREIGN (B) PETITION (I) SUNSTAR (S) BOIS ROUSSEL (S) GUNDOMAR (C) PHALARIS (B) SWEEP (I) BOLD BIDDER (I/C) HABITAT (B) PHARIS II (B) SWYNFORD (C) BOLD RUCKUS (I/C) HAIL TO REASON (C) PHAROS (I) T.V. -

2020 International List of Protected Names

INTERNATIONAL LIST OF PROTECTED NAMES (only available on IFHA Web site : www.IFHAonline.org) International Federation of Horseracing Authorities 03/06/21 46 place Abel Gance, 92100 Boulogne-Billancourt, France Tel : + 33 1 49 10 20 15 ; Fax : + 33 1 47 61 93 32 E-mail : [email protected] Internet : www.IFHAonline.org The list of Protected Names includes the names of : Prior 1996, the horses who are internationally renowned, either as main stallions and broodmares or as champions in racing (flat or jump) From 1996 to 2004, the winners of the nine following international races : South America : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil Asia : Japan Cup, Melbourne Cup Europe : Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Queen Elizabeth II Stakes North America : Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf Since 2005, the winners of the eleven famous following international races : South America : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil Asia : Cox Plate (2005), Melbourne Cup (from 2006 onwards), Dubai World Cup, Hong Kong Cup, Japan Cup Europe : Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Irish Champion North America : Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf The main stallions and broodmares, registered on request of the International Stud Book Committee (ISBC). Updates made on the IFHA website The horses whose name has been protected on request of a Horseracing Authority. Updates made on the IFHA website * 2 03/06/2021 In 2020, the list of Protected -

2019 Media Guide NYRA.Com 1 TABLE of CONTENTS

2019 Media Guide NYRA.com 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS HISTORY 2 Table of Conents 3 General Information 4 History of The New York Racing Association, Inc. (NYRA) 5 NYRA Officers and Officials 6 Belmont Park History 7 Belmont Park Specifications & Map 8 Saratoga Race Course History 9 Saratoga Leading Jockeys and Trainers TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE 10 Saratoga Race Course Specifications & Map 11 Saratoga Walk of Fame 12 Aqueduct Racetrack History 13 Aqueduct Racetrack Specifications & Map 14 NYRA Bets 15 Digital NYRA 16-17 NYRA Personalities & NYRA en Espanol 18 NYRA & Community/Cares 19 NYRA & Safety 20 Handle & Attendance Page OWNERS 21-41 Owner Profiles 42 2018 Leading Owners TRAINERS 43-83 Trainer Profiles 84 Leading Trainers in New York 1935-2018 85 2018 Trainer Standings JOCKEYS 85-101 Jockey Profiles 102 Jockeys that have won six or more races in one day 102 Leading Jockeys in New York (1941-2018) 103 2018 NYRA Leading Jockeys BELMONT STAKES 106 History of the Belmont Stakes 113 Belmont Runners 123 Belmont Owners 132 Belmont Trainers 138 Belmont Jockeys 144 Triple Crown Profiles TRAVERS STAKES 160 History of the Travers Stakes 169 Travers Owners 173 Travers Trainers 176 Travers Jockeys 29 The Whitney 2 2019 Media Guide NYRA.com AQUEDUCT RACETRACK 110-00 Rockaway Blvd. South Ozone Park, NY 11420 2019 Racing Dates Winter/Spring: January 1 - April 20 BELMONT PARK 2150 Hempstead Turnpike Elmont, NY, 11003 2019 Racing Dates Spring/Summer: April 26 - July 7 GENERAL INFORMATION GENERAL SARATOGA RACE COURSE 267 Union Ave. Saratoga Springs, NY, 12866