Public-Data File 92-20 Iceberg Production in the Prince

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Holocene Glacier Fluctuations

Quaternary Science Reviews 111 (2015) 9e34 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Quaternary Science Reviews journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/quascirev Invited review Holocene glacier fluctuations * Olga N. Solomina a, b, , Raymond S. Bradley c, Dominic A. Hodgson d, Susan Ivy-Ochs e, f, Vincent Jomelli g, Andrew N. Mackintosh h, Atle Nesje i, j, Lewis A. Owen k, Heinz Wanner l, Gregory C. Wiles m, Nicolas E. Young n a Institute of Geography RAS, Staromonetny-29, 119017, Staromonetny, Moscow, Russia b Tomsk State University, Tomsk, Russia c Department of Geosciences, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, MA 012003, USA d British Antarctic Survey, High Cross, Madingley Road, Cambridge CB3 0ET, UK e Institute of Particle Physics, ETH Zurich, 8093 Zurich, Switzerland f Institute of Geography, University of Zurich, 8057 Zurich, Switzerland g Universite Paris 1 Pantheon-Sorbonne, CNRS Laboratoire de Geographie Physique, 92195 Meudon, France h Antarctic Research Centre, Victoria University Wellington, New Zealand i Department of Earth Science, University of Bergen, N-5020 Bergen, Norway j Uni Research Klima, Bjerknes Centre for Climate Research, N-5020 Bergen Norway k Department of Geology, University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH 45225, USA l Institute of Geography and Oeschger Centre for Climate Change Research, University of Bern, Switzerland m Department of Geology, The College of Wooster, Wooster, OH 44691, USA n Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, Columbia University, Palisades, NY, USA article info abstract Article history: A global overview of glacier advances and retreats (grouped by regions and by millennia) for the Received 15 July 2014 Holocene is compiled from previous studies. The reconstructions of glacier fluctuations are based on Received in revised form 1) mapping and dating moraines defined by 14C, TCN, OSL, lichenometry and tree rings (discontinuous 22 November 2014 records/time series), and 2) sediments from proglacial lakes and speleothems (continuous records/ Accepted 27 November 2014 time series). -

Popular Summary Glacier Ice Mass Fluctuations and Fault Instability In

popular summary Glacier Ice Mass Fluctuations and Fault Instability in Tectonically Active Southern Alaska by Jeanne M. Sauber and Bruce F. Molnia Across southern Alaska the northwest directed subduction of the Pacific plate is accompanied by accretion of the Yakutat terrane to continental Alaska. This has led to high tectonic strain rates and dramatic topographic relief of more than 5000 meters within 15 km of the Gulf of Alaska coast. The glaciers of this area are extensive and include large glaciers undergoing wastage (glacier retreat and thinning) and surges. The large glacier ice mass changes perturb the tectonic rate of deformation at a variety of temporal and spatial scales. We estimated surface displacements and stresses associated with ice mass fluctuations and tectonic loading by examining GPS geodetic observations and numerical model predictions. Although the glacial fluctuations perturb the tectonic stress field, especially at shallow depths, the largest contribution to ongoing crustal deformation is horizontal tectonic strain due to plate convergence. Tectonic forces are thus the primary force responslble for major eartnquakes. Xowever, for geodefic sites located < 10-20 km from major ice mass fluctuations, the changes of the solid Earth due to ice loading and unloading are an important aspect of interpreting geodetic results. The ice changes associated with Bering Glacier’s most recent surge cycle are large enough to cause discernible surface displacements. Additionally, ice mass fluctuations associated with the surge cycle can modify the shod-term seismicity rates in a local region. For the thrust faulting environment of the study region a large decrease in ice load may cause an increase in seismic rate in a region close to failure whereas ice loading may inhibit thrust faulting. -

Tsunamis Following the 1992 Nicaragua and Flores Events

Pure Appl. Geophys. 176 (2019), 2771–2793 Ó 2019 Springer Nature Switzerland AG https://doi.org/10.1007/s00024-019-02244-x Pure and Applied Geophysics Twenty-Five Years of Progress in the Science of ‘‘Geological’’ Tsunamis Following the 1992 Nicaragua and Flores Events 1 EMILE A. OKAL Abstract—We review a set of 47 tsunamis of geological origin Mindanao, Philippines, and in 1983 in the Sea of (triggered by earthquakes, landslides or volcanoes) which have Japan. While substantial progress was made in the occurred over the past 25 years and provided significant new insight into theoretical, experimental, field, or societal aspects of 1970s and 1980s on the theoretical and experimental tsunami science. Among the principal developments in our com- front (e.g., Hammack 1973; Ward 1980; Bernard and mand of various aspects of tsunamis, we earmark the development Milburn 1985), scientists still lacked the motivation of the W-phase inversion for the low-frequency moment tensor of the parent earthquake; the abandonment of the concept of a max- provided by exceptional and intriguing field imum earthquake magnitude for a given subduction zone, observations. controlled by simple plate properties; the development and The two tsunamis of 02 September 1992 in implementation of computer codes simulating the interaction of tsunamis with initially dry land at beaches, thus introducing a Nicaragua and 12 December 1992 in Flores Island, quantitative component to realistic tsunami warning procedures; Indonesia provided our community with a wealth of and the recent in situ investigation of current velocities, in addition challenges which spawned a large number of new to the field of surface displacements, during the interaction of investigations covering the observational, experi- tsunamis with harbors. -

Paul R. Carlson, Bruce F. Molnia and William P. Levy This Report Is

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF INTERIOR GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CONTINUOUS ACOUSTIC PROFILES AND SEDIMENTOLOGIC DATA FROM R/V SEA SOUNDER CRUISE (S-l-76), EASTERN GULF OF ALASKA Paul R. Carlson, Bruce F. Molnia and William P. Levy OPEN FILE REPORT 80-65 This report is preliminary and has not been edited or reviewed for conformity with Geological Survey standards and nomenclature Menlo Park, California INTRODUCTION In June 1976, a scientific party from the U.S. Geological Survey, conducted a high resolution geophysical and seafloor sediment sampling cruise (S-l-76) in the eastern Gulf of Alaska between Sitka and Seward (fig. 1), to obtain data on seafloor hazards pertinent to OCS oil and gas lease sale activity. We had previously participated in four cruises to this area and had begun developing a regional "picture" of the geologic hazards on the continental shelf, between Prince William Sound and Yakutat Bay. Cruise S-l-76 was planned to investigate, in greater detail, specific hazards previously identified on this portion of the shelf and to run some reconnaissance lines on the shelf east of Yakutat Bay. In addition to the data collected on the shelf, we used this opportunity to investigate the three major navigable bays that interupt the coast line in this portion of the eastern Gulf of Alaska (Lituya Bay, Yakutat Bay, and Icy Bay-fig. 1). This report contains a list of the seismic reflection records and shipboard logs that are publicly available and includes trackline maps and a text. Included in the report are: (1) examples of characteristic seismic profiles, (2) descriptions of geologic hazards observed on specific profiles, and (3) summary descriptions of sediment samples and bottom photographs. -

Characteristics of the Last Five Surges of Lowell Glacier, Yukon, Canada, Since 1948

Journal of Glaciology, Vol. 60, No. 219, 2014 doi: 10.3189/2014JoG13J134 113 Characteristics of the last five surges of Lowell Glacier, Yukon, Canada, since 1948 Alexandre BEVINGTON, Luke COPLAND Department of Geography, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT. Field observations, aerial photographs and satellite images are used to reconstruct the past surges of Lowell Glacier, Yukon, Canada, since 1948 based on the timing of terminus advances. A total of five surges occurred over this time, each with a duration of 1±2 years. The time between successive surges ranged from 12 to 20 years, and appears to have been shortening over time. The relatively short advance and quiescent phases of Lowell Glacier, together with rapid increases in velocity during surges, suggest that the surging is controlled by a hydrological switch. The 2009±10 surge saw ablation area velocities increase by up to two orders of magnitude from quiescent velocities, and the terminus increase in area by 5.1 km2 and in length by up to 2.85 km. This change in area was the smallest since 1948, and follows the trend of decreasing surge extents over time. This decrease is likely driven by a strongly negative surface mass balance of Lowell Glacier since at least the 1970s, and means that the current town site of Haines Junction is very unlikely to be flooded by damming caused by any future advances of the glacier under the current climate regime. KEYWORDS: glacier flow, glacier mass balance, glacier surges, remote sensing 1. INTRODUCTION this mechanism, it is hypothesized that the glacier is frozen to The Yukon±Alaska border hosts the highest concentration of its bed when ice is thin, but that the bed reaches the pressure- surge-type glaciers in North America, with 136 out of the melting point when the ice thickens due to increased 204 surge-type glaciers identified in western North America insulation from low atmospheric temperatures. -

Downloaded At

Authors Bretwood Higman, Dan H Shugar, Colin P Stark, Göran Ekström, Michele N Koppes, Patrick Lynett, Anja Dufresne, Peter J Haeussler, Marten Geertsema, Sean Gulick, Andrew Mattox, Jeremy G Venditti, Maureen A L Walton, Naoma McCall, Erin Mckittrick, Breanyn MacInnes, Eric L Bilderback, Hui Tang, Michael J Willis, Bruce Richmond, Robert S Reece, Chris Larsen, Bjorn Olson, James Capra, Aykut Ayca, Colin Bloom, Haley Williams, Doug Bonno, Robert Weiss, Adam Keen, Vassilios Skanavis, and Michael Loso This article is available at CU Scholar: https://scholar.colorado.edu/geol_facpapers/32 www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN The 2015 landslide and tsunami in Taan Fiord, Alaska Bretwood Higman1, Dan H. Shugar 2, Colin P. Stark3, Göran Ekström3, Michele N. Koppes4, Patrick Lynett5, Anja Dufresne6, Peter J. Haeussler7, Marten Geertsema8, Sean Gulick 9, 1 10 11 9 Received: 8 November 2017 Andrew Mattox , Jeremy G. Venditti , Maureen A. L. Walton , Naoma McCall , Erin Mckittrick1, Breanyn MacInnes12, Eric L. Bilderback13, Hui Tang14, Michael J. Willis 15, Accepted: 24 July 2018 Bruce Richmond11, Robert S. Reece16, Chris Larsen17, Bjorn Olson1, James Capra18, Aykut Ayca5, Published: xx xx xxxx Colin Bloom12, Haley Williams4, Doug Bonno2, Robert Weiss14, Adam Keen5, Vassilios Skanavis5 & Michael Loso 19 Glacial retreat in recent decades has exposed unstable slopes and allowed deep water to extend beneath some of those slopes. Slope failure at the terminus of Tyndall Glacier on 17 October 2015 sent 180 million tons of rock into Taan Fiord, Alaska. The resulting tsunami reached elevations as high as 193 m, one of the highest tsunami runups ever documented worldwide. Precursory deformation began decades before failure, and the event left a distinct sedimentary record, showing that geologic evidence can help understand past occurrences of similar events, and might provide forewarning. -

Bibliography of United States Landslide Maps and Reports Christopher S. Alger and Earl E. Brabb1 Open-File Report 85-585 This Re

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Bibliography of United States landslide maps and reports Christopher S. Alger and Earl E. Brabb 1 Open-File Report 85-585 This report is preliminary and has not been reviewed for conformity with U.S. Geological Survey editorial standards and stratigraphic nomenclature. 1 Menlo Park, California Contents Page Introductlon......................................... 1 Text References...................................... 8 Bibliographies With Landslide References............. 8 Multi State-United States Landslide Maps and Reports. 8 Alabama.............................................. 9 Alaska............................................... 9 American Samoa....................................... 14 Arizona.............................................. 14 Arkansas............................................. 16 California........................................... 16 Colorado............................................. 41 Connecticut.......................................... 51 Delaware............................................. 51 District of Columbia................................. 51 Florida.............................................. 51 Georgi a.............................................. 51 Guam................................................. 51 Hawa i i............................................... 51 Idaho................................................ 52 II1i noi s............................................. 54 Indiana............................................. -

302 7.2. Glacially Induced Faulting in Alaska Jeanne Sauber, Chris

7.2. Glacially Induced Faulting in Alaska Jeanne Sauber, Chris Rollins, Jeffrey T. Freymueller, Natalia A. Ruppert Abstract Southern Alaska provides an ideal setting to assess how surface mass changes can influence crustal deformation and seismicity amidst rapid tectonic deformation. Since the end of the Little Ice Age, the glaciers of southern Alaska have undergone extensive wastage, retreating by kilometers and thinning by hundreds of meters. Superimposed on this are seasonal mass fluctuations due to snow accumulation and rainfall of up to meters of equivalent water height in fall and winter, followed by melting of gigatons of snow and ice in spring and summer and changes in permafrost. These processes produce stress changes in the solid Earth that modulate seismicity and promote failure on upper-crustal faults. Here we quantify and review these effects and how they combine with tectonic loading to influence faulting in the southeast, St. Elias and southwest regions of mainland Alaska. 7.2.1. Introduction and Tectonic Setting In southern Alaska, a strong seasonal cycle of snow accumulation and melt is superimposed on a high rate of interannual glacier mass wastage. The magnitudes of both are spatially and temporally variable, as seen in Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE)-derived observations across the region (Fig. 7.2.1). These mass changes occur directly atop the southern Alaska plate boundary zone, which transitions from mainly strike-slip faulting in southeast Alaska to mainly upper-crustal thrusting in the St. Elias region to subduction along the Alaska-Aleutian megathrust further west. Figure. 7.2.1 a. Overview of study region and locations of major glaciers. -

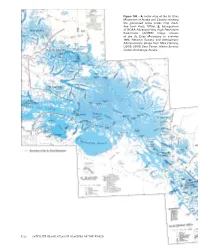

A, Index Map of the St. Elias Mountains of Alaska and Canada Showing the Glacierized Areas (Index Map Modi- Fied from Field, 1975A)

Figure 100.—A, Index map of the St. Elias Mountains of Alaska and Canada showing the glacierized areas (index map modi- fied from Field, 1975a). B, Enlargement of NOAA Advanced Very High Resolution Radiometer (AVHRR) image mosaic of the St. Elias Mountains in summer 1995. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration image from Mike Fleming, USGS, EROS Data Center, Alaska Science Center, Anchorage, Alaska. K122 SATELLITE IMAGE ATLAS OF GLACIERS OF THE WORLD St. Elias Mountains Introduction Much of the St. Elias Mountains, a 750×180-km mountain system, strad- dles the Alaskan-Canadian border, paralleling the coastline of the northern Gulf of Alaska; about two-thirds of the mountain system is located within Alaska (figs. 1, 100). In both Alaska and Canada, this complex system of mountain ranges along their common border is sometimes referred to as the Icefield Ranges. In Canada, the Icefield Ranges extend from the Province of British Columbia into the Yukon Territory. The Alaskan St. Elias Mountains extend northwest from Lynn Canal, Chilkat Inlet, and Chilkat River on the east; to Cross Sound and Icy Strait on the southeast; to the divide between Waxell Ridge and Barkley Ridge and the western end of the Robinson Moun- tains on the southwest; to Juniper Island, the central Bagley Icefield, the eastern wall of the valley of Tana Glacier, and Tana River on the west; and to Chitistone River and White River on the north and northwest. The boundar- ies presented here are different from Orth’s (1967) description. Several of Orth’s descriptions of the limits of adjacent features and the descriptions of the St. -

Seasonal Fluctuations in the Advance of a Tidewater Glacier and Potential Causes: Hubbard Glacier, Alaska, USA

Journal of Glaciology, Vol. 54, No. 186, 2008 401 Seasonal fluctuations in the advance of a tidewater glacier and potential causes: Hubbard Glacier, Alaska, USA J. Brent RITCHIE, Craig S. LINGLE, Roman J. MOTYKA, Martin TRUFFER Geophysical Institute, University of Alaska Fairbanks, 903 Koyukuk Drive, Fairbanks, Alaska 99775-7320, USA E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT. Satellite imagery has been used to acquire seasonal terminus positions of tidewater Hubbard Glacier, Alaska, USA, from 1992 to 2006. During this 15 year time period, the width-averaged advance of the entire terminus has been 620 m at a mean rate of 35 m a–1. Seasonal fluctuation of the terminus ranges from 150 to 200 m on average and varies spatially. A section of the terminus, near a narrow gap where the glacier has now twice closed off 40 km long Russell Fiord, exhibited little to no mean advance during this time period but displayed seasonal fluctuations of 300–500 m. Seasonal variability in surface ice speeds and surface sea-water temperatures was also observed; both are potential forcing mechanisms for terminus fluctuations. Seasonal changes in sea-water temperature of 10–128C, as well as seasonal changes in subglacial freshwater discharge, are inferred to influence calving and submarine melting at the terminus, driving seasonal variations. Displacements of the medial moraine separating Hubbard and Valerie Glaciers at the terminus suggest surge-like pulses of the latter, with a periodicity of several years. The timing of these pulses suggests they may influence the Hubbard terminus near Gilbert Point and have implications for future closures of Russell Fiord. -

Holocene Glacier Fluctuations in Alaska

Quaternary Science Reviews 28 (2009) 2034–2048 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Quaternary Science Reviews journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/quascirev Holocene glacier fluctuations in Alaska David J. Barclay a,*, Gregory C. Wiles b, Parker E. Calkin c a Geology Department, State University of New York College at Cortland, Cortland, NY 13045, USA b Department of Geology, The College of Wooster, Wooster, OH 44691, USA c Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research, University of Colorado, Boulder, CO 80309, USA article info abstract Article history: This review summarizes forefield and lacustrine records of glacier fluctuations in Alaska during the Received 9 May 2008 Holocene. Following retreat from latest Pleistocene advances, valley glaciers with land-based termini Received in revised form were in retracted positions during the early to middle Holocene. Neoglaciation began in some areas by 15 January 2009 4.0 ka and major advances were underway by 3.0 ka, with perhaps two distinct early Neoglacial Accepted 29 January 2009 expansions centered respectively on 3.3–2.9 and 2.2–2.0 ka. Tree-ring cross-dates of glacially killed trees at two termini in southern Alaska show a major advance in the AD 550s–720s. The subsequent Little Ice Age (LIA) expansion was underway in the AD 1180s–1320s and culminated with two advance phases respectively in the 1540s–1710s and in the 1810s–1880s. The LIA advance was the largest Holocene expansion in southern Alaska, although older late Holocene moraines are preserved on many forefields in northern and interior Alaska. Tidewater glaciers around the rim of the Gulf of Alaska have made major advances throughout the Holocene. -

Understanding Abundance Patterns of a Declining Seabird: Implications for Monitoring

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Wildlife Biology Faculty Publications Wildlife Biology 2007 Understanding Abundance Patterns of a Declining Seabird: Implications for Monitoring Michelle L. Kissling Mason Reid Paul M. Lukacs University of Montana - Missoula, [email protected] Scott M. Gende Stephen B. Lewis Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/wildbio_pubs Part of the Life Sciences Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Kissling, Michelle L.; Reid, Mason; Lukacs, Paul M.; Gende, Scott M.; and Lewis, Stephen B., "Understanding Abundance Patterns of a Declining Seabird: Implications for Monitoring" (2007). Wildlife Biology Faculty Publications. 68. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/wildbio_pubs/68 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Wildlife Biology at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wildlife Biology Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Ecological Applications , 17(8), 2007, pp. 2164–2174 Ó 2007 by the Ecological Society of America UNDERSTANDING ABUNDANCE PATTERNS OF A DECLINING SEABIRD: IMPLICATIONS FOR MONITORING 1,6 2 3 4 5 MICHELLE L. K ISSLING , MASON REID , PAUL M. L UKACS , SCOTT M. G ENDE , AND STEPHEN B. L EWIS 1U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, 3000 Vintage Boulevard, Suite 201, Juneau, Alaska 99801 USA 2National Park Service, Wrangell-St. Elias National Park and Preserve, P.O. Box 439, Copper Center, Alaska 99573 USA 3Colorado Division of Wildlife, 317 W. Prospect Road, Fort Collins, Colorado 80526 USA 4National Park Service, Glacier Bay Field Station, 3100 National Park Road, Juneau, Alaska 99801 USA 5Alaska Department of Fish and Game, Division of Wildlife Conservation, P.O.