Amateur Achievements Olympic Games Results

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Npg Hschools Popart.Qxd

Sport Resource Box Introduction Welcome to the Sport resource box. This resource is for teachers and group leaders working with children with Special Educational Needs. This box contains resources to support your self-directed visit to the National Portrait Gallery. The resource box contains: • Information about six portraits of sportsmen and sportswomen. • Questions to discuss with your group. • Cross-curricular activities to try in the gallery or back at school after your visit. • Pictures and handling objects to use with your group in the gallery as you explore the portraits. This icon indicates a suggested activity that incorporates handling objects and/or pictures. You will find these in the resource box. NPG P323 NPG 6832 NPG 5835 NPG x77026 NPG 6669 NPG x128143 Sport Resource Box: 1 of 27 Sport Resource Box Introduction This box is themed around sport. These resources will help you explore: • Celebrated sportsmen and sportswomen. • The sports they played and their achievements. • Your pupils’ own ideas, likes and dislikes about sport. In the lead up to the 2012 London Olympics, sportsmen and sportswomen will be included in the National Portrait Gallery’s changing displays and new commissions. The portraits included in this box may not be on display when you visit. You may wish to use the large copies of the portraits that are included in this resource box, or use alternative portraits with the questions below. Finding alternative sports portraits Use the Portrait Explorer computers in the IT Gallery to check if the portraits are on display or look for alternatives to use. You can browse portraits under the ‘Olympians and Paralympians’ category or search by name. -

Dec 2004 Current List

Fighter Opponent Result / RoundsUnless specifiedDate fights / Time are not ESPN NetworkClassic, Superbouts. Comments Ali Al "Blue" Lewis TKO 11 Superbouts Ali fights his old sparring partner Ali Alfredo Evangelista W 15 Post-fight footage - Ali not in great shape Ali Archie Moore TKO 4 10 min Classic Sports Hi-Lites Only Ali Bob Foster KO 8 21-Nov-1972 ABC Commentary by Cossell - Some break up in picture Ali Bob Foster KO 8 21-Nov-1972 British CC Ali gets cut Ali Brian London TKO 3 B&W Ali in his prime Ali Buster Mathis W 12 Commentary by Cossell - post-fight footage Ali Chuck Wepner KO 15 Classic Sports Ali Cleveland Williams TKO 3 14-Nov-1966 B&W Commentary by Don Dunphy - Ali in his prime Ali Cleveland Williams TKO 3 14-Nov-1966 Classic Sports Ali in his prime Ali Doug Jones W 10 Jones knows how to fight - a tough test for Cassius Ali Earnie Shavers W 15 Brutal battle - Shavers rocks Ali with right hand bombs Ali Ernie Terrell W 15 Feb, 1967 Classic Sports Commentary by Cossell Ali Floyd Patterson i TKO 12 22-Nov-1965 B&W Ali tortures Floyd Ali Floyd Patterson ii TKO 7 Superbouts Commentary by Cossell Ali George Chuvalo i W 15 Classic Sports Ali has his hands full with legendary tough Canadian Ali George Chuvalo ii W 12 Superbouts In shape Ali battles in shape Chuvalo Ali George Foreman KO 8 Pre- & post-fight footage Ali Gorilla Monsoon Wrestling Ali having fun Ali Henry Cooper i TKO 5 Classic Sports Hi-Lites Only Ali Henry Cooper ii TKO 6 Classic Sports Hi-Lites Only - extensive pre-fight Ali Ingemar Johansson Sparring 5 min B&W Silent audio - Sparring footage Ali Jean Pierre Coopman KO 5 Rumor has it happy Pierre drank before the bout Ali Jerry Quarry ii TKO 7 British CC Pre- & post-fight footage Ali Jerry Quarry ii TKO 7 Superbouts Ali at his relaxed best Ali Jerry Quarry i TKO 3 Ali cuts up Quarry Ali Jerry Quarry ii TKO 7 British CC Pre- & post-fight footage Ali Jimmy Ellis TKO 12 Ali beats his old friend and sparring partner Ali Jimmy Young W 15 Ali is out of shape and gets a surprise from Young Ali Joe Bugner i W 12 Incomplete - Missing Rds. -

This Is a Terrific Book from a True Boxing Man and the Best Account of the Making of a Boxing Legend.” Glenn Mccrory, Sky Sports

“This is a terrific book from a true boxing man and the best account of the making of a boxing legend.” Glenn McCrory, Sky Sports Contents About the author 8 Acknowledgements 9 Foreword 11 Introduction 13 Fight No 1 Emanuele Leo 47 Fight No 2 Paul Butlin 55 Fight No 3 Hrvoje Kisicek 6 3 Fight No 4 Dorian Darch 71 Fight No 5 Hector Avila 77 Fight No 6 Matt Legg 8 5 Fight No 7 Matt Skelton 93 Fight No 8 Konstantin Airich 101 Fight No 9 Denis Bakhtov 10 7 Fight No 10 Michael Sprott 113 Fight No 11 Jason Gavern 11 9 Fight No 12 Raphael Zumbano Love 12 7 Fight No 13 Kevin Johnson 13 3 Fight No 14 Gary Cornish 1 41 Fight No 15 Dillian Whyte 149 Fight No 16 Charles Martin 15 9 Fight No 17 Dominic Breazeale 16 9 Fight No 18 Eric Molina 17 7 Fight No 19 Wladimir Klitschko 185 Fight No 20 Carlos Takam 201 Anthony Joshua Professional Record 215 Index 21 9 Introduction GROWING UP, boxing didn’t interest ‘Femi’. ‘Never watched it,’ said Anthony Oluwafemi Olaseni Joshua, to give him his full name He was too busy climbing things! ‘As a child, I used to get bored a lot,’ Joshua told Sky Sports ‘I remember being bored, always out I’m a real street kid I like to be out exploring, that’s my type of thing Sitting at home on the computer isn’t really what I was brought up doing I was really active, climbing trees, poles and in the woods ’ He also ran fast Joshua reportedly ran 100 metres in 11 seconds when he was 14 years old, had a few training sessions at Callowland Amateur Boxing Club and scored lots of goals on the football pitch One season, he scored -

Pugilistic Death and the Intricacies of Fighting Identity

Copyright By Omar Gonzalez 2019 A History of Violence, Masculinity, and Nationalism: Pugilistic Death and the Intricacies of Fighting Identity By Omar Gonzalez, B.A. A Thesis Submitted to the Department of History California State University Bakersfield In Partial Fulfillment for the Degree of Master of Arts in History 2019 A Historyof Violence, Masculinity, and Nationalism: Pugilistic Death and the Intricacies of Fighting Identity By Omar Gonzalez This thesishas beenacce ted on behalf of theDepartment of History by their supervisory CommitteeChair 6 Kate Mulry, PhD Cliona Murphy, PhD DEDICATION To my wife Berenice Luna Gonzalez, for her love and patience. To my family, my mother Belen and father Jose who have given me the love and support I needed during my academic career. Their efforts to raise a good man motivates me every day. To my sister Diana, who has grown to be a smart and incredible young woman. To my brother Mario, whose kindness reaches the highest peaks of the Sierra Nevada and who has been an inspiration in my life. And to my twin brother Miguel, his incredible support, his wisdom, and his kindness have not only guided my life but have inspired my journey as a historian. i ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This thesis is a result of over two years of research during my time at CSU Bakersfield. First and foremost, I owe my appreciation to Dr. Stephen D. Allen, who has guided me through my challenging years as a graduate student. Since our first encounter in the fall of 2016, his knowledge of history, including Mexican boxing, has enhanced my understanding of Latin American History, especially Modern Mexico. -

Black-History-Month Champions

As we conclude Black History Month, we take a look at a few of the iconic trailblazing black boxers who have made a huge impact on the Amateur boxing scene. There are many more boxers who are also deserving to be among this group. However, the ones chosen have had significant impact and have all gone on to inspire (or will inspire) the next generation of Black boxers in our great sport. Randy began boxing aged 12 for the Leamington Boys Club, In winning the Senior Title, Randy also became the youngest where he won 95 out of 100 amateur contests. He became Senior ABA champion at only 17 years old. He repeated the feat the only British amateur boxer to win the Junior and Senior the following year in 1946, then turned professional, where he National ABA titles in the same year, in 1945. continued to shine. One of the greatest amateur boxers ever produced in this country. Originally from Leicester, he however boxed his entire amateur Champion in every tournament he ever entered, and listed in the career for Standard Triumph ABC in Coventry. Won the Senior ABA Guinness Book of World Records as the only British boxer to win National Title in 1981 at Light-Middleweight and won a Bronze all 10 amateur titles, Errol also won a European under-19 Gold medal at the European Championships the same year. Captained medal in 1982. England team from 1980 to 1983. Won Olympic Gold at Super-Heavyweight at Sydney in 2000, Twice won the Senior National ABA Championship (1997 and 1998) thereby becoming Great Britain’s first Boxing Gold medallist since for Repton, and won Commonwealth Gold in 1998. -

Boxing Edition

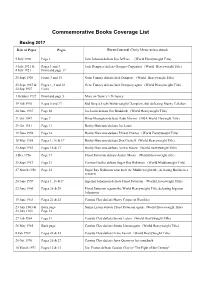

Commemorative Books Coverage List Boxing 2017 Date of Paper Pages Event Covered (Daily Mirror unless stated) 5 July 1910 Page 3 Jack Johnson defeats Jim Jeffries (World Heavyweight Title) 3 July 1921 & Pages 1 and 3 Jack Dempsey defeats Georges Carpentier (World Heavyweight Title) 4 July 1921 Front and page 17 25 Sept 1926 Front, 3 and 15 Gene Tunney defeats Jack Dempsey (World Heavyweight Title) 23 Sept 1927 & Pages 1, 3 and 18 Gene Tunney defeats Jack Dempsey again (World Heavyweight Title) 24 Sep 1927 Front 1 October 1927 Front and page 5 More on Tunney v Dempsey 19 Feb 1930 Pages 5 and 22 Kid Berg is Light Welterweight Champion after defeating Mushy Callahan 24 June 1937 Page 30 Joe Louis defeats Jim Braddock (World Heavyweight Title) 21 Oct 1947 Page 7 Rinty Monaghan defeats Dado Marino (NBA World Flyweight Title) 29 Oct 1951 Page 11 Rocky Marciano defeats Joe Louis 19 June 1954 Page 14 Rocky Marciano defeats Ezzard Charles (World Heavyweight Title) 18 May 1955 Pages 1, 16 & 17 Rocky Marciano defeats Don Cockell (World Heavyweight Title) 23 Sept 1955 Pages 16 & 17 Rocky Marciano defeats Archie Moore (World Heavyweight Title) 3 Dec 1956 Page 17 Floyd Patterson defeats Archie Moore (World Heavyweight title) 25 Sept 1957 Page 23 Carmen Basilio defeats Sugar Ray Robinson (World Middleweight Title) 27 March 1958 Page 23 Sugar Ray Robinson wins back the Middleweight title, defeating Basilio in a rematch 28 June 1959 Pages 1, 16 &17 Ingemar Johansson defeats Floyd Patterson (World Heavyweight Title) 22 June 1960 Pages 28 & 29 Floyd Patterson -

December January:Layout 1.Qxd

The voice of the taxi trade’s only independent organisation Issue 215 Dec. 2013/Jan. 2014 WHERE DO WE INSIDE TFL’S CYCLING UTOPIA GO FROM HERE? PAGES 4&5 NEWS LCDC writes to Commissioner Sir Peter Hendy WALKER ON THE MARCH over concerns PAGE 9 for the cab NEWS trade’s future LCDC VISITS LONDON Full story TAXI COMPANY on page 3 PAGE 17 2 Issue 215 - December 2013/January 2014 Editorial Grant Davis engage in a more positive and meaningful collaboration. Published by Since the last edition of The By working together we can The London Cab Drivers’ Club Ltd. Badge there seems to be a lot secure the long term future of Unit A 303.2, more willingness from TFL to the world’s finest taxi service. Tower Bridge Business Complex Tower Point, 100 Clements Road consult properly with the cab Southwark, London SE16 4DG trade. LCDC visits LTC factory However, at the end of the day Last week myself and Club sec Telephone: 020 7232 0676 and despite another meeting on Darryl Cox visited the LTC E-mail for membership enquiries: the 3rd December, nothing has factory in Coventry to see just E-mail: [email protected] changed. how things were developing and Web: lcdcorg.wordpress.com The LCDC again raised its to bring us up to speed with LTC Editor: Grant Davis concerns at the meeting with plans for the future. Garrett Emerson and Steve Whilst there we also took the The Badge is distributed free to the Licensed London Cab Trade. Burton that the changes that have opportunity to raise our concerns For advertising enquiries please contact the office on been implemented will not work with them regarding the new 020 7394 5553 or E-mail: [email protected] and will have dire long term changes implemented by TfL. -

Boston Arts Festival

VOL. 123 - NO. 34 BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS, AUGUST 23, 2019 $.35 A COPY 109 th Madonna del Soccorso - Fisherman’s Feast by Matt Conti, NorthEndWaterfront.com The 109th Fisherman’s Feast kicked off last weekend con- tinuing the tradition of the North End’s oldest running Italian festival. The feast hon- ors Madonna Del Soccorso Di Sciacca with ceremonies at the Fisherman’s Club on North & Lewis Streets. Opening ceremonies fell on Assumption Day, August 15th, so all the Madonna groups joined for a special proces- sion and blessing including the societies of Santa Maria Di Anzano, Madonna delle Grazie and Madonna Della Cava. For the annual Blessing of the Fishing Waters, the statue of the Madonna di Sciacca was carried by society members to Boston Harbor to the waterfront where a blessing was made by Fr. Brian on the site of the former Italian fl eet in Boston Harbor. A special tribute was made this year to the late “Capt” Ray Bono with speeches by family members. A large crowd fi lled the park for the ceremony that concluded with the throwing of fl owers into the harbor. On the night before the Red Arrows fl ew over Boston Madonna Del Soccorso Society Members (Photo by Matt Conti, NorthEndWaterfront.con) Harbor, it was a flight of a more spiritual kind in in honor of Madonna del After an 8-hour procession angels on balconies recited meet the Madonna Del Soccorso Boston’s North End with the Soccorso di Sciacca. The 2019 during the day, Fisherman’s an Italian devotion followed Di Sciacca. -

Foreign Ai~D

. U. S. NAVAL BASE GUANTANAMO BAY, CUBA Foreign Ai~d Committee Considers Extending Program WASHINGTON (AP)--The Senate Foreign Relations Committee agreed yesterday that the United States should stay in the foreign aid business, and Con- gress appeared headed toward a stopgap resolution to keep the program alive. But controversy loomed over the the duration of any such revival mea- sure, and the shape of a long-term foreign aid formula. The White House said adoption of a resolution to continue foreign aid spending authority past Nov. 15 is imperative. And a Pentagon spokesman said military assistance "is absolutely essen- tial" in U.S. strategic planning. TUESDAY NOVEMBER-2 1971 I The Foreign Relations Committee spent some 90 minutes behind closed doors discussing the future and the impact of last Friday night's Senate vote that killed the $2.9 billion foreign aid authorization bill. No votes were taken at the committee session and no formal decisions Tidal Wave (Please see AID, page 2) 'Something Devastates Will be Indian State done' NEW DELHI, India (AP)--A cyclone and 16-foot tidal wave have slammed into India's east coast, and polit- I-Fuibright ical leaders reported the loss of 15,000 to 20,000 lives in this lat- est natural disaster on the rim of the Bay of Bengal. The wave and 100-mile-an-hour winds hit Friday night, but the de- vastation was so complete that word of its catastrophic proportions did not reach the outside world until Elections Foreshadow 1972 yesterday. The 'Indian government radio re- WASHINGTON (AP)--Elections across step in the overturning of Nixon. -

Astronauts in Lunar Orbit After Blastoff from Moon

ri . v f- ■ ,, Average Dally Net Press Ron 'I’hfe-Weather For The Week Ended Mostly cloudy, warm, humid through Wednesday with chance July 81, m i of ahowers/thunderstorms; low tonight near. 70 with consider 14,890 able night rain. Manchester— A City of Village Charm (Classified Advertising on Page 17) PRICE FIFTEEN CENTS VOL. LXXXX, NO. 257 (TWENTY PAGES) man(:hester, conn., Monday, august 2,1971 Steel Strike Averted But Pact Settles Astronauts in Lunar Orbit Prices Hiked PITTSBURGH (AP)— Rail Strike U.S. Steel Corp., the in After Blastoff from Moon dustry pacesetter, hiked WASHINGTON (A P)— Negotiators announced to prices on virtually all prod day a contract settlement providing 42 per cent wage ucts today, a little more hikes over 42 months for about 200,000 trainmen, and SPACE CENTER, Hous than 12 hours after the said pickets would be removed froih 10-strike-bound ton (A P)—Apollo 15 as steel industry and the railroads, -------------------- : tronauts David R. Scott and James B. Irwin blast United Steelworkers Settlement of the 18-day old President Charles Luna of the ' strikes in the dispute involving striking-AFO-CTO United Trans- ed off safely from the agreed on a strike-avert all of the nation’s major rail- portatlon Union, ing contract. moon today after three roads came after a 17-hour <‘nve arp very happy that this days of historic lunar ex The m oveby U.S. Steel came marathon bargaining session at long dispute has ended and that as most of the nation’s steel ploration. A television the Labor Department. -

Name: Ken Buchanan Career Record: Click Nationality: British

Name: Ken Buchanan Career Record: click Nationality: British Birthplace: Edinburgh, Scotland Hometown: Edinburgh, Scotland, United Kingdom Born: 1945-06-28 Stance: Orthodox Height: 5′ 7½″ Reach: 178 Manager: Eddie Thomas Trainer: Gil Clancy 1965 ABA featherweight champion International Boxing Hall of Fame Bio Further Reading: The Tartan Legend: The Autobiography http://www.stv.tv/info/sportExclusive/20070618/Ken_Buchanan_interview_180607 Ken Buchanan was born in Edinburgh, Scotland, on 28 June 1945, to p a r e n t s Tommy and Cathie. both of whom were very supportive of their son's sporting ambitions throughout his early life. However, it wa s Ken's aunt, Joan and Agnes, who initially encouraged the youngster's enthusiasm for boxing. In 1952. the pair were shopping for Christmas presents for Ken and his cousin. Robert Barr. when they saw a pair of boxing gloves and it occurred to them that the two boys often enjoyed some playful sparring together. So. at the age of seven, the young Buchanan received his first pair of boxing gloves. It was another casual act, this time by father Tommy that sparked young Ken's interest in competitive boxing. One Saturday, when the family had finished shopping, Tommy took his son to the cinema to see The Joe Louis Story and Ken decided he'd like to join a boxing club. Tommy agreed. and the eight-year-old joined one of Scotland's best clubs. the Sparta. Two nights a week, alongside 50 other youths, young Ken learned how to box and before long he had won his first medal – with a three-round points win in the boys' 49lb (three stone seven pound) division. -

Two Day Autograph Auction Day 1 Saturday 02 November 2013 11:00

Two Day Autograph Auction Day 1 Saturday 02 November 2013 11:00 International Autograph Auctions (IAA) Office address Foxhall Business Centre Foxhall Road NG7 6LH International Autograph Auctions (IAA) (Two Day Autograph Auction Day 1 ) Catalogue - Downloaded from UKAuctioneers.com Lot: 1 tennis players of the 1970s TENNIS: An excellent collection including each Wimbledon Men's of 31 signed postcard Singles Champion of the decade. photographs by various tennis VG to EX All of the signatures players of the 1970s including were obtained in person by the Billie Jean King (Wimbledon vendor's brother who regularly Champion 1966, 1967, 1968, attended the Wimbledon 1972, 1973 & 1975), Ann Jones Championships during the 1970s. (Wimbledon Champion 1969), Estimate: £200.00 - £300.00 Evonne Goolagong (Wimbledon Champion 1971 & 1980), Chris Evert (Wimbledon Champion Lot: 2 1974, 1976 & 1981), Virginia TILDEN WILLIAM: (1893-1953) Wade (Wimbledon Champion American Tennis Player, 1977), John Newcombe Wimbledon Champion 1920, (Wimbledon Champion 1967, 1921 & 1930. A.L.S., Bill, one 1970 & 1971), Stan Smith page, slim 4to, Memphis, (Wimbledon Champion 1972), Tennessee, n.d. (11th June Jan Kodes (Wimbledon 1948?), to his protégé Arthur Champion 1973), Jimmy Connors Anderson ('Dearest Stinky'), on (Wimbledon Champion 1974 & the attractive printed stationery of 1982), Arthur Ashe (Wimbledon the Hotel Peabody. Tilden sends Champion 1975), Bjorn Borg his friend a cheque (no longer (Wimbledon Champion 1976, present) 'to cover your 1977, 1978, 1979 & 1980), reservation & ticket to Boston Francoise Durr (Wimbledon from Chicago' and provides Finalist 1965, 1968, 1970, 1972, details of the hotel and where to 1973 & 1975), Olga Morozova meet in Boston, concluding (Wimbledon Finalist 1974), 'Crazy to see you'.