Comprehensive Water Management Plan 2000 Update

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Water Quality Assessment of Select Lakes Within the Little Fork River Watershed

Water Quality Assessment of Select Lakes within the Little Fork River Watershed Rainy River Basin St. Louis, Itasca, and Koochiching Counties, Minnesota Minnesota Pollution Control Agency Water Monitoring Section Lakes and Streams Monitoring Unit August, 2010 Author Jesse Anderson Editing Steve Heiskary Dana Vanderbosch Data Provided By Itasca County Soil and Water Conservation District, Itasca Community College, MN DNR Fisheries (Rian Reed) and Volunteers from the Sturgeon Chain of Lakes Assessment Report of Selected Lakes Within the Little Fork River Watershed Rainy River Basin Intensive Watershed Monitoring 2008 Minnesota Pollution Control Agency Water Monitoring Section Lakes and Streams Monitoring Unit wq-ws3-09030005 Minnesota Pollution Control Agency 520 Lafayette Road North Saint Paul, MN 55155-4194 http://www.pca.state.mn.us 651-296-6300 or 800-657-3864 toll free TTY 651-282-5332 or 800-657-3864 toll free Available in alternative formats The MPCA is reducing printing and mailing costs by using the Internet to distribute reports and information to wider audience. For additional information, see the Web site: www.pca.state.mn.us/water/lakereport.html Table of Contents Executive Summary ......................................................................................................................................... 1 Introduction to Monitoring Strategy and Sources of Monitoring Data ............................................................ 2 Environmental Setting and Distribution of Lakes........................................................................................... -

Little Fork River, Minnesota 1. the Area

Little Fork River , Minnesota 1. The area surrounding the river: a. The Little Fork watershed is located in Itasca, St. Louis, and Koochichinz Counties, Minnesota. It rises in a rather flat region in St. Louis County and follows a meandering course to the northwest through Koochiching County to its junction with the Rainy River about 19 miles below Little Fork, Minnesota. The area is a hummocky rolling surface made up of morainic deposits and glacial drift laid over a bedrock composed largely of granitic, volcanic, and metamorphic rocks. The upper basin is covered with dense cedar forests with some trees up to three feet in diameter. Needles form a thick layer over the ground with ferns turning the forest floor into a green carpet. In the lower basin the forest changes to hardwoods with elm predominating. Dense brush covers the forest floor. Farming is the major land use other than timber production in the area of Minnesota, but terrain limits areas where farming is practical. Transportation routes in this area are good due to its proximity to International Falls, Minnesota, a major border crossing into Canada. U. S. 53 runs north-south to International Falls about 25 miles east of the basin. U. S. 71 runs northeast-southwest and crosses the river at. Little Fork, Minnesota, and follows the U. S. /Canadian border to International Falls. Minnesota Route 217 connects these two major north-south routes in an east-west direction from Little Fork, Minnesota. Minnesota Route 65 follows the river southward from Little Fork, Minnesota. b. Population within a 50-mile radius was estimated at 173, 000 in. -

East Rat Root River Peatland SNA Koochiching County

East Rat Root River Peatland SNA Koochiching County N48 31.039 N48 31.026, W93 10.998 W93 11.813 N48 30.921, W93 11.000 N48 30.918 W93 10.343 N48 30.822 W93 11.819 N48 30.807 Koochiching State Forest W93 10.341 N48 30.820 W93 11.649 N48 30.572 trail W93 10.020 N48 30.569 W93 9.704 N48 30.400 N48 30.388 W93 12.312 W93 11.657 N48 30.361 N48 30.359 W93 10.033 W93 9.707 N48 30.142 W93 10.039 Voyageurs National Park N48 29.951 W93 9.693 N48 29.951 W93 8.390 N48 29.755 W93 12.329 winter trail N48 29.541 W93 12.662 N48 29.438 W93 12.052 unimproved ro ad N48 29.516 N48 29.518 N48 29.301 W93 9.371 W93 9.044 W93 12.401 Parking trail N48 29.298 W93 13.823 N48 29.297 W93 12.664 N48 29.302 N48 29.301 N48 29.298 N48 29.300 W93 11.460 W93 10.946 W93 10.031 W93 9.698 N48 29.301 W93 12.337 N48 29.303 N48 29.109 W93 12.058 W93 10.501 Arrowhead StateN48 Trail 28.860 N48 28.864 W93 12.327 W93 10.673 © 2017 MinnesotaSeasons.com. All rights reserved. Based on Minnesota DNR data dated 10/27/2017 East Rat Root River Peatland SNA Koochiching County N48 31.039 N48 31.026, W93 10.998 W93 11.813 N48 30.921, W93 11.000 N48 30.918 W93 10.343 N48 30.822 W93 11.819 N48 30.807 Koochiching State Forest W93 10.341 N48 30.820 W93 11.649 N48 30.572 trail W93 10.020 N48 30.569 W93 9.704 N48 30.400 N48 30.388 W93 12.312 W93 11.657 N48 30.361 N48 30.359 W93 10.033 W93 9.707 N48 30.142 W93 10.039 Voyageurs National Park N48 29.951 W93 9.693 N48 29.951 W93 8.390 N48 29.755 W93 12.329 winter trail N48 29.541 W93 12.662 N48 29.438 W93 12.052 unimproved ro ad N48 29.516 N48 29.518 N48 29.301 W93 9.371 W93 9.044 W93 12.401 Parking trail N48 29.298 W93 13.823 N48 29.297 W93 12.664 N48 29.302 N48 29.301 N48 29.298 N48 29.300 W93 11.460 W93 10.946 W93 10.031 W93 9.698 N48 29.301 W93 12.337 N48 29.303 N48 29.109 W93 12.058 W93 10.501 Arrowhead StateN48 Trail 28.860 N48 28.864 W93 12.327 W93 10.673 © 2017 MinnesotaSeasons.com. -

Koochiching State Forest

Grassy Narrows Grassy Island Grindstone Tilson Bay 0.2 mi. Frank Island Bay Bald Rock Rainy Lake W Point Tilson Bay W 0.3 mi. Rainy Lake 0.3 mi. Neil Point 0.3 mi. Little American 0.2 mi. W 11 Island U. S. F. S. W 6.5 mi. to International Falls TILSON BAY Frank Bay X HIKING TRAIL Frank Bay X W X 11 W W X DETAIL 11 11 1.3 k. Krause Bay Tilson Creek 0.7 k. X X Island View Dove Point Black Bay Ski and Green Trail 461 Dove Hiking Trails X Island 0.3 k. 96 W Sha Sha X Voyageurs Point 0.3 k. 0.1 k. X X 0.9 k. Steeprock Island Voyageurs X 0.1 k. Tilson National Creek X X X 2.3 k. Blue Trail East Voyageurs Orange Trail X Trail 1.6 k. 0.5 k. 0.3 k. 1.2 k. Tilson Trail X National Park 1.0 k. Perry Point X U. S. F. S. TILSON 0.6 k. CREEK 0.4 k. 96 SKI Yellow Trail Park TRAIL 0.6 k. X 1150 Black Bay Narrows 0.9 k. Black Bay 0.4 k. 1130 KOOCHICHING STATE FOREST X 1140 1.3 k. TRAILS OWNERSHIP FACILITIES 1.1 k. KOOCHICHING Non Motorized Trails State Forest Land Parking 1120 Visitor Center U. S. F. S. easy more difficult Black Bay County Land Red Trail Boat Ramp 1110 W = Hiking/Walking National Land Fishing Pier X = Skiing STATE Trail Shelter X LOOKING FOR MORE INFORMATION ? Snowmobile Trails 0.8 k. -

1~11~~~~11Im~11M1~Mmm111111111111113 0307 00061 8069

LEGISLATIVE REFERENCE LIBRARY ~ SD428.A2 M6 1986 -1~11~~~~11im~11m1~mmm111111111111113 0307 00061 8069 0 428 , A. M6 1 9 This document is made available electronically by the Minnesota Legislative Reference Library as part of an ongoing digital archiving project. http://www.leg.state.mn.us/lrl/lrl.asp (Funding for document digitization was provided, in part, by a grant from the Minnesota Historical & Cultural Heritage Program.) State Forest Recreation Areas Minnesota's 56 state forests contain over 3.2 million acres of state owned lands which are administered by the Department of Natural Resources, Division of Forestry. State forest lands are managed to produce timber and other forest crops, provide outdoor recreation, protect watershed, and perpetuate rare and distinctive species of flora and fauna. State forests are multiple use areas that are managed to provide a sustained yield of renewable resources, while maintaining or improving the quality of the forest. Minnesota's state forests provide unlimited opportunities for outdoor recreationists to pursue a variety of outdoor activities. Berry picking, mushroom hunting, wildflower identification, nature photography and hunting are just a few of the unstructured outdoor activities which can be accommodated in state forests. For people who prefer a more structured form of recreation, Minnesota's state forests contain over 50 campgrounds, most located on lakes or canoe routes. State forest campgrounds are of the primitive type designed to furnish only the basic needs of individuals who camp for the enjoyment of the outdoors. Each campsite consists of a cleared area, fireplace and table. In addition, pit toilets, garbage cans and drinking water may be provided. -

Class G Tables of Geographic Cutter Numbers: Maps -- by Region Or

G4127 NORTHWESTERN STATES. REGIONS, NATURAL G4127 FEATURES, ETC. .C8 Custer National Forest .L4 Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail .L5 Little Missouri River .M3 Madison Aquifer .M5 Missouri River .M52 Missouri River [wild & scenic river] .O7 Oregon National Historic Trail. Oregon Trail .W5 Williston Basin [geological basin] .Y4 Yellowstone River 1305 G4132 WEST NORTH CENTRAL STATES. REGIONS, G4132 NATURAL FEATURES, ETC. .D4 Des Moines River .R4 Red River of the North 1306 G4142 MINNESOTA. REGIONS, NATURAL FEATURES, ETC. G4142 .A2 Afton State Park .A4 Alexander, Lake .A42 Alexander Chain .A45 Alice Lake [Lake County] .B13 Baby Lake .B14 Bad Medicine Lake .B19 Ball Club Lake [Itasca County] .B2 Balsam Lake [Itasca County] .B22 Banning State Park .B25 Barrett Lake [Grant County] .B28 Bass Lake [Faribault County] .B29 Bass Lake [Itasca County : Deer River & Bass Brook townships] .B3 Basswood Lake [MN & Ont.] .B32 Basswood River [MN & Ont.] .B323 Battle Lake .B325 Bay Lake [Crow Wing County] .B33 Bear Head Lake State Park .B333 Bear Lake [Itasca County] .B339 Belle Taine, Lake .B34 Beltrami Island State Forest .B35 Bemidji, Lake .B37 Bertha Lake .B39 Big Birch Lake .B4 Big Kandiyohi Lake .B413 Big Lake [Beltrami County] .B415 Big Lake [Saint Louis County] .B417 Big Lake [Stearns County] .B42 Big Marine Lake .B43 Big Sandy Lake [Aitkin County] .B44 Big Spunk Lake .B45 Big Stone Lake [MN & SD] .B46 Big Stone Lake State Park .B49 Big Trout Lake .B53 Birch Coulee Battlefield State Historic Site .B533 Birch Coulee Creek .B54 Birch Lake [Cass County : Hiram & Birch Lake townships] .B55 Birch Lake [Lake County] .B56 Black Duck Lake .B57 Blackduck Lake [Beltrami County] .B58 Blue Mounds State Park .B584 Blueberry Lake [Becker County] .B585 Blueberry Lake [Wadena County] .B598 Boulder Lake Reservoir .B6 Boundary Waters Canoe Area .B62 Bowstring Lake [Itasca County] .B63 Boy Lake [Cass County] .B68 Bronson, Lake 1307 G4142 MINNESOTA. -

Request for Waiver

form revised 3/18/2020 MANAGED CARE SYSTEMS P.O. Box 64882, St. Paul, MN 55164-0882 Telephone: 651-201-5100 Email: [email protected] Request for Waiver Plan Year: 2021 Please ensure that information contained on this waiver request coincides with information provided on the geographical access maps and provider list submitted with this application. 1. Name and Title of Person Submitting this Document: Carrier Name Network Network ID Network Structure* Blue Plus Minnesota High Value Network MNN012 <select one> Name Title Date Enrollees in Network* Eric Hoag Vice President, Provider Relations 7/29/2020 2. By submitting this form, the above-referenced confirms: A. That person submitting this request has personal knowledge of the network contracting process involved in this submission; and B. That access cannot be met for the following provider type(s). Include the county and reason(s) for not meeting the requirements. Percent Total Percent Not Percent Available Provider Type County Reason Code Notes Affected Enrollees* Enrollees Affected Covered* Providers Included Based on a review of Internal records and provider directories (between April 1-30, 2020) such as Quest Analytics, Medicare Physician Compare and provider websites of several partners organizations including Riverwood Health Care Center, Cuyuna Regional Medical Center, Fairview Health and St. Lukes Hospital, no General Hospitals are available to cover 100% of this county. These directories give us the most accurate and complete information when determining if a provider is available and offering these services. Quest Analytics is used by many health plans as well as Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) for determining network adequacy. -

Upper Lower Red Lake Watershed

Upper/Lower Red Lake Watershed Monitoring and Assessment Report June 2017 Authors The MPCA is reducing printing and mailing costs MPCA Upper/Lower Red Lake Watershed Report by using the Internet to distribute reports and Team: information to wider audience. Visit our website Dave Dollinger, Nate Sather, Joseph Hadash, Mike for more information. Bourdaghs, David Duffey, Kevin Stroom, Bruce Monson, Shawn Nelson, Andrew Streitz, Sophia MPCA reports are printed on 100% post-consumer Vaughan, Andrew Butzer recycled content paper manufactured without chlorine or chlorine derivatives. Contributors / acknowledgements Citizen Stream Monitoring Program Volunteers Minnesota Department of Natural Resources Minnesota Department of Health Minnesota Department of Agriculture Red Lake Department of Natural Resources Red Lake Watershed District Project dollars provided by the Clean Water Fund (from the Clean Water, Land and Legacy Amendment). Minnesota Pollution Control Agency 520 Lafayette Road North | Saint Paul, MN 55155-4194 | 651-296-6300 | 800-657-3864 | Or use your preferred relay service. | [email protected] This report is available in alternative formats upon request, and online at www.pca.state.mn.us. Document number: wq-ws3-09020302b Contents List of Acronyms ..................................................................................................................................................... i Executive summary .............................................................................................................................................. -

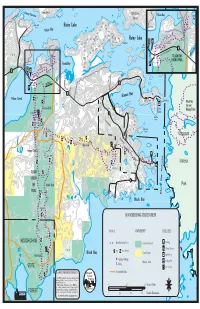

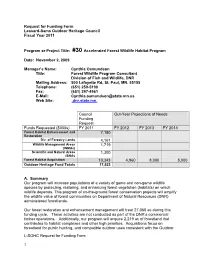

L-SOHC Request for Funding Form 1 Request for Funding Form Lessard

Request for Funding Form Lessard-Sams Outdoor Heritage Council Fiscal Year 2011 Program or Project Title: #30 Accelerated Forest Wildlife Habitat Program Date: November 2, 2009 Manager’s Name: Cynthia Osmundson Title: Forest Wildlife Program Consultant Division of Fish and Wildlife, DNR Mailing Address: 500 Lafayette Rd, St. Paul, MN. 55155 Telephone: (651) 259-5190 Fax: (651) 297-4961 E-Mail: [email protected] Web Site: .dnr.state.mn. Council Out-Year Projections of Needs Funding Request Funds Requested ($000s) FY 2011 FY 2012 FY 2013 FY 2014 Forest Habitat Enhancement and 7,180 Restoration Div. of Forestry Lands 4,161 Wildlife Management Areas 1,719 (WMAs) Scientific and Natural Areas 1,300 (SNAs Forest Habitat Acquisition 10,343 4,960 8,000 8,000 Outdoor Heritage Fund Totals 17,523 A. Summary Our program will increase populations of a variety of game and non-game wildlife species by protecting, restoring, and enhancing forest vegetation (habitats) on which wildlife depends. This program of on-the-ground forest conservation projects will amplify the wildlife value of forest communities on Department of Natural Resources (DNR) administered forestlands. Our forest restoration and enhancement management will treat 27,060 ac during this funding cycle. These activities are not conducted as part of the DNR’s commercial timber operations. Additionally, our program will acquire 2,219 ac of forestland that contributes to habitat complexes and other high priorities. Acquisitions focus on forestland for public hunting, and compatible outdoor uses consistent with the Outdoor L-SOHC Request for Funding Form 1 Recreation Act (M.S. -

Little Fork River Channel Stability and Geomorphic Assessment Final

Little Fork River Channel Stability and Geomorphic Assessment Final Report Submitted to the MPCA Impaired Waters and Stormwater Program August 13, 2007 Karen B. Gran, Brad Hansen, John Nieber University of Minnesota 0 Table of Contents Introduction..............................................................................................................1 Objectives ................................................................................................................1 Background..............................................................................................................3 1. Geomorphic classification of the Little Fork River Watershed...........................9 2. Historical air photo analysis of landscape changes............................................30 3. Floodplains.........................................................................................................47 4. Post-settlement alluvium....................................................................................57 5. Mid-channel island at confluence ......................................................................65 6. Basin hydrology and bankfull flow....................................................................71 Summary................................................................................................................79 Works Cited ...........................................................................................................83 Appendix A: Spatial datasets used for analyses ...................................................86 -

State Forest Recreation Guide

Activities abound Camping in State www.mndnr.gov/state_forests in a state forest. Forests... Choose your fun: Your Way Minnesota There are four different ways of • Hiking camping in a state forest. State • Mountain biking 1. Individual Campsites- campsites designated for individuals or single Forest • Horseback riding families. The sites are designed to furnish • Geocaching only the basic needs of the camper. Most consist of a cleared area, fire ring, table, • Canoeing vault toilets, garbage cans, and drinking Recreation water. Campsites are all on a first-come, • Snowmobiling first-served basis. Fees are collected at the sites. Guide • Cross-County Skiing 2. Group Campsites- campsites designated • Biking for larger groups.The sites are designed to furnish only the basic needs of the • OHV riding camper. Most consist of a cleared area, • Camping fire ring, table, vault toilets, garbage cans, and drinking water. Group sites are all on • Fishing a first-come, first-served basis. Fees are collected at the sites. • Hunting 3. Horse Campsites- campsites where • Berry picking horses are allowed. The sites are designed to furnish only the basic needs of the • Birding camper. Most consist of a cleared area, fire ring, table, vault toilets, garbage cans, • Wildlife viewing and drinking water. In addition, these • Wildflower viewing campsites also may have picket lines and compost bins for manure disposal. The State Forest Recreation Guide is published by the Minnesota Department of Campsites are all on a first-come, first- Natural Resources, Division of Forestry, 500 Lafaytte Road, St.Paul, Mn 55155- 4039. Phone 651-259-5600. Written by Kim Lanahan-Lahti; Graphic Design by served basis. -

Minnesota Statutes 2018, Section 89.021

1 MINNESOTA STATUTES 2018 89.021 89.021 STATE FORESTS. Subdivision 1. Established. There are hereby established and reestablished as state forests, in accordance with the forest resource management policy and plan, all lands and waters now owned by the state or hereafter acquired by the state, excepting lands acquired for other specific purposes or tax-forfeited lands held in trust for the taxing districts unless incorporated therein as otherwise provided by law. History: 1943 c 171 s 1; 1963 c 332 s 1; 1982 c 511 s 9; 1990 c 473 s 3,6 Subd. 1a. Boundaries designated. The commissioner of natural resources may acquire by gift or purchase land or interests in land adjacent to a state forest. The commissioner shall propose legislation to change the boundaries of established state forests for the acquisition of land adjacent to the state forests, provided that the lands meet the definition of forest land as defined in section 89.001, subdivision 4. History: 2011 c 3 s 3 Subd. 2. Badoura State Forest. History: 1963 c 332 s 1; 1967 c 514 s 1; 1980 c 424; 2018 c 186 s 10 subd 1 Subd. 3. Battleground State Forest. History: 1963 c 332 s 1 Subd. 4. Bear Island State Forest. History: 1963 c 332 s 1; 2016 c 154 s 15 subd 1 Subd. 5. Beltrami Island State Forest. History: 1943 c 171 s 1; 1963 c 332 s 1; 2000 c 485 s 20 subd 1; 2004 c 262 art 2 s 14 Subd. 6. Big Fork State Forest. History: 1963 c 332 s 1 Subd.