Religious Educator: Perspectives on the Restored Gospel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MARY JANE WOODGER 275 E Joseph Smith Building Brigham Young University Provo, Utah 84602 (801) 422-9029 Work

MARY JANE WOODGER 275 E Joseph Smith Building Brigham Young University Provo, Utah 84602 (801) 422-9029 Work PROFESSIONAL TRACK 2009-present Professor of Church History and Doctrine, BYU 2003-2009 Associate Professor of Church History and Doctrine, BYU 1997-2003 Assistant Professor of Church History and Doctrine, BYU 1994-99 Faculty, Department of Ancient Scripture, BYU Salt Lake Center 1980-97 Department Chair of Home Economics, Jordan School District, Midvale Middle School, Sandy, Utah EDUCATION 1997 Ed.D. Brigham Young University, Educational Leadership, Minor: Church History and Doctrine 1992 M.Ed. Utah State University, Secondary Education, Emphasis: American History 1980 B.S. Brigham Young University, Home Economics Education HONORS 2012 The Harvey B. Black and Susan Easton Black Outstanding Publication Award: Presented in recognition of an outstanding published scholarly article or academic book in Church history, doctrine or related areas for Against the Odds: The Life of George Albert Smith (Covenant Communications, Inc., 2011). 2012 Alice Louise Reynolds Women-in-Scholarship Lecture 2006 Brigham Young University Faculty Women’s Association Teaching Award 2005 Utah State Historical Society’s Best Article Award “Non Utah Historical Quarterly,” for “David O. McKay’s Progressive Educational Ideas and Practices, 1899-1922.” 1998 Kappa Omicron Nu, Alpha Tau Chapter Award of Excellence for research on David O. McKay 1997 The Crystal Communicator Award of Excellence (An International Competition honoring excellence in print media, 2,900 entries in 1997. Two hundred recipients awarded.) Research consultant for David O. McKay: Prophet and Educator Video 1994 Midvale Middle School Applied Science Teacher of the Year 1987 Jordan School District Vocational Teacher of the Year PUBLICATIONS Authored Books (18) Casey Griffiths and Mary Jane Woodger, 50 Relics of the Restoration (Springville, Utah: Cedar Fort Press, 2020). -

Constructing Dutch America in the Twentieth Century

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Dissertations Graduate College 4-2012 Faithful Remembering: Constructing Dutch America in the Twentieth Century David E. Zwart Western Michigan University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations Part of the Anthropology Commons, Religion Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Zwart, David E., "Faithful Remembering: Constructing Dutch America in the Twentieth Century" (2012). Dissertations. 23. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations/23 This Dissertation-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FAITHFUL REMEMBERING: CONSTRUCTING DUTCH AMERICA IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY by David E. Zwart A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History Advisor: Edwin Martini, Ph.D. Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan April 2012 THE GKADUATE COLLEGE WESTERN MICHIGAN UNIVERSITY KALAMAZOO, MICHIGAN March 12, 2012 Date WE HEREBY APPROVETHE DISSERTATIONSUBMITTED BY David E. Zwart ENTITLED Faithful Remembering: Constructing Dutch America intheTwentieth Century AS PARTIAL FULFILLMENTOFTHE REQUIREMENTS FORTHE DECREE OF Doctor ofPhilosophy History (Department) History (Program) Mitch Kachun, PMX Dissertation ReviewCommittee Member Robert Ulfri, Pt»,D. DissertationReviewCommittee Member APPROVED i Date .A^QTtl rUXl' DeanorTheGraduate College FAITHFUL REMEMBERING: CONSTRUCTING DUTCH AMERICA IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY David E. Zwart, Ph.D. Western Michigan University, 2012 The people of the Dutch-American community constructed and maintained a strong ethnoreligion identity in the twentieth despite pressures to join the mainstream of the United States. -

Building Inventory Brigham Young University Provo, Utah October 2019

Building Inventory Brigham Young University Provo, Utah October 2019 Yearly Comparison: October 2017 October 2018 October 2019 Buildings per Asset Class Appropriated 112 125 112 Designated Account 1 1 1 Revenue 158 155 154 Investment Property 0 0 13 Total Buildings 271 281 281 Gross Square Feet per Asset Class Appropriated 5,391,346 5,808,286 5,389,161 Designated Account 85,691 85,691 85,691 Revenue 4,024,214 4,155,237 4,224,910 Investment Property 0 0 302,361 Total Gross Square Feet 9,501,251 10,049,214 10,002,123 Total Acreage of Main Campus 557.20 557.20 557.20 Changes in gross square footage are due to selling of PRSH, acquiring additional space at the LNDC and various minor construction projects; square footage reconciliations for academic, auxiliary, and housing buildings. Buildings are listed in alphabetical order by name followed by a cross-index on abbreviation sequence. Summaries are also included showing major-user categories, buildings under construction and in planning, square footage by condition, and type of use. The building abbreviations listed are for mail services, directories, class scheduling, and the University database system. Missionary Training Center buildings are not included in summaries, but are listed separately for reference. Also listed for reference are Aspen Grove, Spanish Fork Farm, BYU Utility Buildings, and Facilities not included in other summaries. This information is not for release to non-BYU agencies without specific approval from the University Administration. Direct any inquiries to the Office of Space Management BRWB 230, ext. 2-5474. (Issued by the Office of Space Management) 1 Condition of Buildings (estimated) Number Gross Sq. -

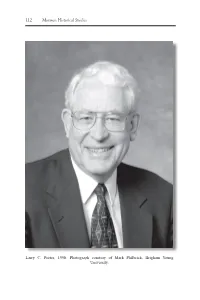

A Conversation with Larry C. Porter 113

112 Mormon Historical Studies Larry C. Porter, 1998. Photograph courtesy of Mark Philbrick, Brigham Young University. Walker: A Conversation with Larry C. Porter 113 The Gentleman Historian: A Conversation with Larry C. Porter Interview by Kyle R. Walker In the spring of 1999, in the midst of my doctoral studies at Brigham Young University, I was teaching in the Department of Church History and Doctrine and beginning to research in the field of Mormon history. It was at this time when I first sought out and met a seasoned historian who was nearing the end of his tenure at BYU. Though it was above and beyond his job description, Professor Larry C. Porter readily agreed to be a part of my dissertation committee, as well as mentor me through a graduate minor in Church History and Doctrine. While I had never taken a class from him, and he certainly was not familiar with me, Larry made every accommodation to ensure that I was provided with accurate research and solid documentation for my dissertation project. As I would occasionally stop by his office, Larry would literally drop everything in order to attend to my research interests. Often times we would go down to the copy machine to photocopy some source that would strengthen my research. Despite his demanding schedule, he often brought to our com- mittee meetings a source or two that he knew I would be interested in, without my having asked for such material. The more I spent time with Larry, the more I became impressed with his modesty and his willingness to sacrifice his valuable time for others. -

BYU Education Week Campus Map PARKING SHUTTLE ROUTES and STOPS DINING See Page 49 for Parking Information

1 BYU Education Week Campus Map PARKING SHUTTLE ROUTES AND STOPS DINING See page 49 for parking information. Blue Route See corresponding numbers on map. Dining information West Stadium—MC—West Stadium is on page 33. VAN SHUTTLES Brown Route 1 The Commons at the Cannon Center Helaman Halls—HFAC—Helaman Halls 2 Cougareat Food Court (WSC) Shuttle vans run between designated stops on campus from Green Route 7:45 a.m. to 4:45 p.m. on Monday; 7:45 a.m. to 10:00 p.m. on 3 Museum of Art (MOA) Café MC—JKB—MC Tuesday through Friday. Please give boarding preference 4 Skyroom Restaurant (WSC) Orange Route to senior and disabled students, and realize that it is your 5 Dining at the Marriott Center (MC) MC—HFAC—MC responsibility to move from class to class or to your place of 6a Jamba Juice (WSC) Pink Route residence. 6b Jamba Juice (SAB) 11c West Stadium—HFAC—West Stadium 7 Cosmo’s Mini Mart (WSC) Shuttles also run between perimeter parking lots and main Purple Route 8 The Wall (WSC) campus frequently. Large, detailed maps of the routes are East Stadium—HFAC—East Stadium University Avenue 9a The Creamery on Ninth (1209 North 900 East) posted at each van top. Red Route 9b Creamery Outlet (CSC) One wheelchair-accessible van is available. To contact the SFH—HFAC—SFH 9c Helaman Halls Creamery Outlet driver of this van, call 385-335-3143 and tell the driver at which Yellow Route Blue Line Deli (TNRB) MTC shuttle stop you are located. -

Near-Death Experiences and Early Mormon Thought

Thought Communication, Speed of Movement, and the Spirit's Ability to Absorb Knowledge: Near-Death Experiences and Early Mormon Thought Brent L. Top, Ph.D. Brigham Young University ABSTRACT- Three of Charles Flynn's (1986) "core elements" of near-death experiences (NDEs) have special interest to members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Mormons) because of their striking similarity to the doctrinal teachings of 19th-century Mormon leaders and theologians. This article illustrates these three NDE characteristics-thought communi cation, speed of movement, and the ability to "absorb" knowledge-by com paring contemporary NDE accounts with both the religious teachings of 19th-century Mormon church leaders and the accepted doctrines of modern Mormonism. Virtually all of the recent studies of near-death experiences (NDEs) have included accounts of those who have "died" discovering en hanced abilities, far beyond earthly abilities, in the areas of commu nication, travel and movement, and the acquisition of knowledge. These three different aspects of the near-death experience, included in Charles Flynn's (1986) list of "core elements" of the NDE, have special interest to Mormons. There are striking similarities between the modern descriptions by NDErs concerning thought communica tion, the speed of their movements, and their ability to absorb knowl edge, and the theological teachings of early Mormon leaders in the Brent L. Ibp, Ph.D., is Associate Professor of Church History and Doctrine at Brigham Young University. Reprint requests should be addressed to Dr. bp at the Department of Church History and Doctrine, 316-E Joseph Smith Building, Brigham Young University, P 0. -

Journal of Mormon History Vol. 25, No. 2, 1999

Journal of Mormon History Volume 25 Issue 2 Article 1 1999 Journal of Mormon History Vol. 25, No. 2, 1999 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/mormonhistory Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation (1999) "Journal of Mormon History Vol. 25, No. 2, 1999," Journal of Mormon History: Vol. 25 : Iss. 2 , Article 1. Available at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/mormonhistory/vol25/iss2/1 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Mormon History by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Journal of Mormon History Vol. 25, No. 2, 1999 Table of Contents CONTENTS LETTERS viii ARTICLES • --David Eccles: A Man for His Time Leonard J. Arrington, 1 • --Leonard James Arrington (1917-1999): A Bibliography David J. Whittaker, 11 • --"Remember Me in My Affliction": Louisa Beaman Young and Eliza R. Snow Letters, 1849 Todd Compton, 46 • --"Joseph's Measures": The Continuation of Esoterica by Schismatic Members of the Council of Fifty Matthew S. Moore, 70 • -A LDS International Trio, 1974-97 Kahlile Mehr, 101 VISUAL IMAGES • --Setting the Record Straight Richard Neitzel Holzapfel, 121 ENCOUNTER ESSAY • --What Is Patty Sessions to Me? Donna Toland Smart, 132 REVIEW ESSAY • --A Legacy of the Sesquicentennial: A Selection of Twelve Books Craig S. Smith, 152 REVIEWS 164 --Leonard J. Arrington, Adventures of a Church Historian Paul M. Edwards, 166 --Leonard J. Arrington, Madelyn Cannon Stewart Silver: Poet, Teacher, Homemaker Lavina Fielding Anderson, 169 --Terryl L. -

Science & Mormonism Series 1

Science & Mormonism Series 1: Cosmos, Earth, and Man Chapter Title: Forging a Friendly Alliance between Mormonism and Science Chapter Author: John W. Welch This book from which this chapter is excerpted is available through Eborn Books: https://ebornbooks.com/shop/non-fiction/mormon-lds/mormon-science/science-and- mormonism-1-cosmos-earth-and-man-hardbound-jeffrey-m-bradshaw/ Recommended Citation John W. Welch, "Forging a Friendly Alliance between Mormonism and Science" in Science & Mormonism Series 1: Cosmos, Earth, and Man, edited by David H. Bailey, Jeffrey M. Bradshaw, John S. Lewis, Gregory L. Smith, and Michael R. Stark (Orem, UT, and Salt Lake City: The Interpreter Foundation and Eborn Books, 2016), https://interpreterfoundation.org/reprints/science-and-mormonism/SM1Chap03.pdf. SCIENCE AND MORMONISM 1: COSMOS, EARTH, AND MAN David H. Bailey, Jeffrey M. Bradshaw, John S. Lewis, Gregory L. Smith, and Michael R. Stark The Interpreter Foundation Eborn Books 2016 © 2016 The Interpreter Foundation. A 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization. The goal of The Interpreter Foundation is to increase understanding of scripture through careful scholarly investigation and analysis of the insights provided by a wide range of ancillary disciplines. We hope to illuminate, by study and faith, the eternal spiritual message of the scriptures — that Jesus is the Christ. Although the Board fully supports the goals and teachings of the Church, the Interpreter Foundation is an independent entity and is not owned, controlled by, or affiliated with The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints or with Brigham Young University. All research and opinions provided are the sole responsibility of their respective authors, and should not be interpreted as the opinions of the Board, nor as official statements of LDS doctrine, belief, or practice. -

1 Joseph Smith and the Kirtland Temple, 1836 Steven C. Harper

HISTORY OF THE CHURCH 1836 Joseph Smith and the Kirtland Temple, 1836 Steven C. Harper Steven C. Harper was an associate professor of Church history and doctrine at Brigham Young University and an editor of The Joseph Smith Papers when this was pub- lished. In one sense, Moroni enlisted the seventeen-year-old seer to save the world when he told young Joseph that he had a role in fulfilling ancient prophecy , adding that “if it were not so, the whole earth would be utterly wast- ed.” (George Edward Anderson, August 1907, Church History Library, image digitally enhanced.) The story of the Kirtland Temple began in Joseph Smith’s bedroom. “When I was about 17 years,” Joseph said, “I had another vision of angels; in the night season, after I had retired to bed; I had not been asleep, but was meditating on my past life and experience. I was well aware I had not kept the commandments, and I repent- ed heartily for all my sins and transgressions, and hum- Kirtland Temple, Kirtland, Ohio. bled myself before him, whose eye surveys all things at a glance. All at once the room was illuminated above The angel’s words obviously made a deep impres- the brightness of the sun; An angel appeared before me.” sion on the teenage seer. Whether he understood all “I am a Messenger sent from God,” he told Joseph, the words that night is not clear, but they remained in introducing himself as Moroni. He said that God had his mind and heart until he witnessed their fulfillment vital work for Joseph to do. -

October 2002 Ensign

THE ENSIGN OF THE CHURCH OF JESUS CHRIST OF LATTER-DAY SAINTS • OCTOBER 2002 Remembering Hiram, Ohio, p. 32 Area Authority Seventies, p. 50 Daniel’s Answer to the King, by Briton Riviere “Then said Daniel unto the king, O king, live for ever. My God hath sent his angel, and hath shut the lions’ mouths, that they have not hurt me: forasmuch as before him innocency was found in me; and also before thee, O king, have I done no hurt. Then was the king exceeding glad for him, and commanded that they should take Daniel up out of the den. So Daniel was taken up out of the den, and no manner of hurt was found upon him, because he believed in his God” (Daniel 6:21–23). COURTESY MANCHESTER ART GALLERY OCTOBER 2002 • VOLUME 32, NUMBER 10 2 FIRST PRESIDENCY MESSAGE Be Not Afraid President James E. Faust 7 Hymn: O Lord, Who Gave Thy Life for Me Alice W. Johnson 8Facing the Fiery Furnace Terry W. Call 11 Jeremiah: As Potter’s Clay Education for Elder Jean A. Tefan Real Life 14 Education for Real Life 14 Elder Henry B. Eyring 22 Part of a Family: Strengthening Relationships Michele Burton Bridging the Distance Kristin Bayles Batchelor 26 Making Choices for Eternity Elder Dieter F. Uchtdorf 31 Confessions of a Den Mother Bette Newton Lang 32 Remembering Hiram, Ohio Mark L. Staker 40 GOSPEL CLASSICS Part of a Family: Oneness in Marriage President Spencer W. Kimball Bridging the 22 Distance 46 Joining in the Mighty Work of God Coleen K. -

Insights on Church Leadership

Insights on Church Leadership Marcus H. Martins, Ph.D. Brigham Young University - Hawaii Copyright © 1993, 1999, 2001 (web edition) by Marcus H. Martins All Rights Reserved This text may be printed or copied for incidental home or Church use This is not an official publication of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints Chapter 9 Prejudice The Prophet Lehi taught that coincidence has no place in the plan of salvation. He said: "... all things have been done in the wisdom of him who knoweth all things.1" In the book of Psalms we find the following statement: "O Lord, how manifold [i.e. marked by diversity or variety] are thy works! In wisdom hast thou made them all: the earth is full of thy riches.2" With the advances in instant communication of the late twentieth century we have engaged in more frequent association with people of nationalities and cultures other than our won than probably any other civilization in the known history. Even in the Church of Christ we see congregations with varying degrees of cultural (i.e. national, ethnic, racial, or linguistic) diversity. This has been a common characteristic of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints since the early days in this dispensation, although today the diversity is more along racial and ethnic lines than ever before. With this diversity comes the need to understand, respect, and accommodate individuals of many cultures in order to build a truly worldwide Zion. But going beyond recent "politically correct" trends, we can use cultural diversity as a significant advantage in the kingdom of God on earth. -

Byu Religious Education WINTER 2010 REVIEW

byu religious education WINTER 2010 REVIEW CALENDAR COMMENTS INTERVIEWS & SPOTLIGHTS STUDENT & TEACHER UPDATES BOOKS Hugh Nibley A Life of Faith, Learning, and Teaching message from the dean’s office Enduring Examples Each year, Religious Education mourns the passing of retired colleagues. In 2009 we lost Daniel H. Ludlow, Clark V. Johnson, Truman G. Madsen, Robert J. Matthews, and E. Dale LeBaron. Each made lasting contributions to BYU and the Church. Clark and Dale, unlike Dan, Truman, and Bob, were not widely known around the Church. But I want to make special mention of them because of their unique and unheralded research projects. Both of them were collectors. Clark Johnson passed away of cancer on July 25, 2009, not long after he and his wife, Cheryl, returned from serving their third mission together. Clark’s research had its focus in Missouri. In 1992 he published his most enduring scholarly work, Mormon Redress Petitions: Documents of the 1833–1838 Confl ict. In Doctrine and Covenants 123:1–6, the Prophet Joseph Smith instructed the Saints to write petitions to the U.S. government detailing their losses after their expulsion from Missouri. They were to request redress for their property. Clark located and transcribed 773 of those petitions and published them in his 830-page book. It is a gold mine of information about people, places, property, Church history, and economics on the American frontier of the 1830s. It will be used as a resource forever. Dale LeBaron died in an auto-pedestrian accident on December 3, 2009. A few years after he joined the Religious Education faculty in 1986, he began a great work of collecting.