How Can Engaging Communities Aid in Developing New Conservation Initiatives?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ward Councillors

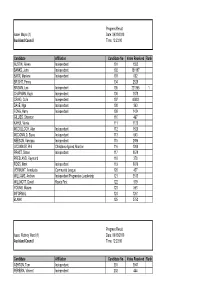

Ward councillors Albany Ward - confirmed Candidate Affiliation Candidate no Votes received Rank WATSON, John Putting People First 225 19,324 1 WALKER, Wayne Putting People First 224 17,938 2 WHYTE, Lisa Auckland Future 226 15,926 LOWE, Graham Auckland Future 223 15,549 BENSCH, John Independent 221 5,126 HENETI, Alezix 222 1,538 INFORMAL 227 74 BLANK 228 3,852 Albert-Eden-Roskill Ward - confirmed Candidate Affiliation Candidate no Votes received Rank CASEY, Cathy City Vision 321 19,256 1 FLETCHER, Christine C&R - Communities & Residents 322 16,925 2 HARRIS, Rob Auckland Future 323 10,000 HAYNES, Peter City Vision 324 9,935 LEE, Benjamin C&R - Communities & Residents 325 9,070 MCKEOWN, Greg Independent 326 8,472 SOKRATOV, Boris Independent 327 2,879 SULLIVAN-TAYLOR, Bridgette 328 1,177 INFORMAL 329 78 BLANK 330 3,867 Franklin Ward - confirmed Bill Cashmore was elected unopposed. Howick Ward - confirmed Candidate Affiliation Candidate no Votes received Rank STEWART, Sharon Independent 388 17,923 1 QUAX, Dick Independent 387 15,516 2 YOUNG, Paul Independent 389 7,046 HAY, David Independent 382 5,757 ZHU, Julie Green Party 390 5,732 CROSS, Matthew 381 5,034 MONTGOMERY, Olivia 386 4,409 KUMAR, Gyanandra Labour 384 3,129 MAMEDOV, Tofik Labour 385 2,743 IRELAND, Ian Colin 383 1,120 INFORMAL 391 164 BLANK 392 1,878 Manukau Ward - confirmed Candidate Affiliation Candidate no Votes received Rank FILIPAINA, Alf Labour 403 17,327 1 COLLINS, Fa'anana Efeso Labour 401 16,500 2 CORBETT, Brendan Respect Our Community Campaign 402 7,738 MUA, Sooalo Setu -

Waiheke Local Board Plan 2017 Ngā Upoko Kōrero Contents

TE MAHERE Ā-ROHE O WAIHEKE 2017 Waiheke Local Board Plan 2017 Ngā upoko kōrero Contents From the Chairs ........................................................................................................... 4 Mihi Our plan at a glance .................................................................................................. 6 Waiheke Local Board area ........................................................................................ 8 Titiro ki te Pane o Horoiwi, Look to the sandbanks at Achilles Point, ka whakapukepuke, ka whakatiketike ki waho rā. rising majestically out there. About local boards and our plans ..........................................................................11 He kawau, he kawau, he kawau! It is the visiting cormorant! He kawau tikitiki ka eke ki te tāhuna tōrea. It has alighted onto the beach of the oystercatcher. Developing our plan ................................................................................................. 13 He kawau tikitiki ka eke ki te tāhuna ki Waitematā. A distinguished visitor has come to the Waitematā. Ko koutou ēna e ngā mataawaka It is you the descendants of the ancient voyagers, Outcomes: i rite ai te kōrero, those who embody the axiom, Ngā waka o Taikehu me he kāhui kātaha The canoes of Taikehu, like shoals of herrings 1. Inclusive planning and placemaking ......................................................... 14 kapi-tai, ka eke! on the tide, you have arrived! Kua eke, hui e, tāiki e! The connections are made! 2. A sustainable economy and positive visitor experience ........................ 18 Te noho nei au i te kūrae i Takaparawhā, So here I sit on the headland at Bastion Point, ka titiro whakawaho ki a koe Aotea and I look out to Great Barrier Island 3. Waiheke’s environment is treasured .......................................................... 22 e tū hihiwa mai rā i te pae o te moana o Hauraki. shimmering on the Hauraki Harbour. Ka hoki whakaroto ake aku mihi ki a Waiheke, Returning my gaze to Waiheke and then 4. -

Attachment 5 Local Board Resolutions

Attachment 5 Local Board Resolutions Contents Albert Eden ............................................................................................................................. 2 Devonport-Takapuna .............................................................................................................. 5 Franklin ................................................................................................................................... 7 Great Barrier ......................................................................................................................... 13 Henderson-Massey ............................................................................................................... 17 Hibiscus and Bays ................................................................................................................ 21 Howick .................................................................................................................................. 28 Kaipatiki ................................................................................................................................ 31 Mangere-Otahuhu ................................................................................................................. 38 Manurewa ............................................................................................................................. 42 Maungakiekie-Tamaki ........................................................................................................... 49 Orakei .................................................................................................................................. -

Auckland Progress Results

Progress Result Issue: Mayor (1) Date: 09/10/2010 Auckland Council Time: 12:23:00 Candidate Affiliation Candidate No Votes Received Rank AUSTIN, Aileen Independent 101 1552 BANKS, John Independent 102 161167 BARR, Marlene Independent 103 692 BRIGHT, Penny 104 2529 BROWN, Len Independent 105 2213651 CHAPMAN, Hugh Independent 106 1878 CRAIG, Colin Independent 107 40483 DAVE, Nga Independent 108 840 FONG, Harry Independent 109 1434 GILLIES, Shannon 110 467 KAHUI, Vinnie 111 1120 MCCULLOCH, Alan Independent 112 1520 MCDONALD, Steve Independent 113 643 NEESON, Vanessa Independent 115 2885 O'CONNOR, Phil Christians Against Abortion 116 1209 PRAST, Simon Independent 117 3578 PRESLAND, Raymond 118 278 ROSS, Mark Independent 119 3076 VERMUNT, Annalucia Communist League 120 427 WILLIAMS, Andrew Independent Progressive Leadership 121 3813 WILLMOTT, David Roads First 122 519 YOUNG, Wayne 123 553 INFORMAL 124 1261 BLANK 125 3752 Progress Result Issue: Rodney Ward (1) Date: 09/10/2010 Auckland Council Time: 12:23:00 Candidate Affiliation Candidate No Votes Received Rank ASHTON, Tom Independent 201 3941 PEREIRA, Vincent Independent 202 444 ROSE, Christine 203 5553 WEBSTER, Penny Independent 204 8063 1 INFORMAL 205 21 BLANK 206 701 Progress Result Issue: Albany Ward (2) Date: 09/10/2010 Auckland Council Time: 12:23:00 Candidate Affiliation Candidate No Votes Received Rank BALOUCH, Uzra Independent 221 736 BELL, Rodney Independent 222 3151 BRADLEY, Ian Independent 223 5273 CONDER, Laurie Independent 224 1419 COOPER, David Independent 225 2821 COOPER, -

Love Our Wetlands

Waiheke Resources Trust - Love Our Wetlands Love Our Wetlands Annual Report 2019-2020 2 Waiheke Resources Trust - Love Our Wetlands Index Project background 2 Toitū te Marae a Tane, Toitū te Marae a Tangaroa, Toitū te Iwi If the land is well and the sea is well, we the people will thrive Why are wetlands important? 3-4 Wetland restoration team 5-6 Our organisation COVID-19 response 7 Waiheke Resources Trust (WRT) was established in 1998 Volunteering and internships 7-8 and became a registered Charitable Trust in 2008. Over time, the Trust’s work on Waiheke has broadened to the following aspects of sustainable living: biodiversity, Building community capacity 9-10 ecological restoration, energy, food resilience, water Project timeline 11 quality and waste minimisation. WRT works to celebrate and protect all the resources Restoring a wetland on Waiheke 12 we have and build capacity and knowledge in the Restoration management phases 13-17 community toward the creation of a resource-full future for all. It seeks to provide the Waiheke community with Funding 18 information, inspiration, innovation and education to make ethical, effective and powerful decisions with sponsors and partners of LOWW 19 respect to sustainability. Workplan 20 Project background Love Our Wetlands Waiheke (LOWW) began as a community partnership between WRT, Waiheke Local Board and the wider Waiheke community in 2015. The project is guided by local experts working with volunteer groups and the Waiheke community towards the ecological restoration and protection of the important wetland habitats and surrounding environments on Waiheke. Email [email protected] Phone Our goals 09 372 2915 Long term ecological restoration of Waiheke's threatened environments. -

Ward and Local Board Boundary Maps and Relevant Population

Current ward population. This is based on population statistics provided through the Local Government Commission for the purpose of reviewing our boundaries. The statistics are a 2017 estimate based on the 2013 census. The council has proposed changes to the Local Government Commission to reduce the non- compliance in the Waitematā and Gulf ward Per cent Population Difference difference per from from Ward Population Members member quota quota Rodney Ward 64,300 1 64,300 -18,560 -22.40 Albany Ward 169,800 2 84,900 2,040 2.46 North Shore Ward 156,800 2 78,400 -4,460 -5.38 Waitākere Ward 176,500 2 88,250 5,390 6.50 Waitematā and Gulf Ward 119,100 1 119,100 36,240 43.74 Whau Ward 84,700 1 84,700 1,840 2.22 Albert-Eden-Roskill Ward 172,200 2 86,100 3,240 3.91 Ōrākei Ward 91,500 1 91,500 8,640 10.43 Maungakiekie-Tāmaki Ward 79,700 1 79,700 -3,160 -3.81 Howick Ward 150,200 2 75,100 -7,760 -9.37 Manukau Ward 168,900 2 84,450 1,590 1.92 Manurewa-Papakura Ward 148,900 2 74,450 -8,410 -10.15 Franklin Ward 74,600 1 74,600 -8,260 -9.97 Total 1,657,200 20 82,860 Current local board population Statistics supplied through the Local Government Commission. Population Board Population Members per member Rodney 64,300 9 7,144 Hibiscus and Bays 104,500 8 13,063 Upper Harbour 65,300 6 10,883 Kaipātiki 94,000 8 11,750 Devonport-Takapuna 62,800 6 10,467 Henderson-Massey 122,300 8 15,288 Waitākere Ranges 54,200 6 9,033 Great Barrier 1,000 5 200 Waiheke 9,630 5 1,926 Waitematā 108,500 7 15,500 Whau 84,700 7 12,100 Albert-Eden 109,200 8 13,650 Puketāpapa 63,000 6 10,500 Ōrākei 91,500 7 13,071 Maungakiekie-Tāmaki 79,700 7 11,386 Howick 150,200 9 16,689 Māngere-Ōtāhuhu 81,100 7 11,586 Ōtara-Papatoetoe 87,800 7 12,543 Manurewa 94,500 8 11,813 Papakura 54,500 6 9,083 Franklin 74,600 9 8,289 Total 1,657,330 Local board subdivisions The following table shows those boards with subdivisions, and their current population. -

Agenda of Ōtara-Papatoetoe Local Board

I hereby give notice that an ordinary meeting of the Ōtara-Papatoetoe Local Board will be held on: Date: Tuesday, 4 May 2021 Time: 12.30pm Meeting Room: Woodside Room, Level 1, Venue: Manukau Civic Building, 31-33 Manukau Station Road, Manukau Ōtara-Papatoetoe Local Board OPEN AGENDA MEMBERSHIP Chairperson Apulu Reece Autagavaia Deputy Chairperson Dawn Trenberth Members Dr Ashraf Choudhary, QSO, JP Dr Ofa Dewes Lotu Fuli Swanie Nelson Ross Robertson, QSO, JP (Quorum 4 members) Carol McGarry Democracy Advisor 28 April 2021 Contact Telephone: +64 27 591 5024 Email: [email protected] Website: www.aucklandcouncil.govt.nz Note: The reports contained within this agenda are for consideration and should not be construed as Council policy unless and until adopted. Should Members require further information relating to any reports, please contact the relevant manager, Chairperson or Deputy Chairperson. Ōtara-Papatoetoe Local Board 04 May 2021 ITEM TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE 1 Welcome 5 2 Apologies 5 3 Declaration of Interest 5 4 Confirmation of Minutes 5 5 Leave of Absence 5 6 Acknowledgements 5 7 Petitions 5 8 Deputations 5 9 Public Forum 5 10 Extraordinary Business 5 11 Notices of Motion 6 12 Governing Body Member Update 7 13 Notice of Motion - Member Lotu Fuli - Retain 11R Birmingham Road in Auckland Council ownership for public use 9 14 Disposal recommendation report 12 15 Highbrook Park Trust Disestablishment 19 16 Ōtara-Papatoetoe Local Board consultation feedback and input into the 10-year Budget 2021-2031 23 17 Decision-making responsibilities policy 41 18 Consideration of Extraordinary Items Page 3 Ōtara-Papatoetoe Local Board 04 May 2021 1 Welcome 2 Apologies At the close of the agenda no apologies had been received. -

Auckland Council ALUPIS Mario

ID Council Issue Last Name First Names Affiliation 3764 AC Mayor - Auckland Council ALUPIS Mario <none> 1537 AC Mayor - Auckland Council AUSTIN Aileen Independent 6141 AC Mayor - Auckland Council BRIGHT Penny Independent 6156 AC Mayor - Auckland Council BROWN Patrick Communist League 1385 AC Mayor - Auckland Council CHEEL Tricia STOP 211 AC Mayor - Auckland Council CRONE Vic Independent 2597 AC Mayor - Auckland Council GOFF Phil Independent 420 AC Mayor - Auckland Council HAY David Independent 6131 AC Mayor - Auckland Council HENETI Alezix <none> 663 AC Mayor - Auckland Council HOLLAND Adam John Auckland Legalise Cannabis 1416 AC Mayor - Auckland Council MARTIN Stan Independent 6181 AC Mayor - Auckland Council NGUYEN Binh Thanh Independent 703 AC Mayor - Auckland Council O'CONNOR Phil Christians Against Abortion 1622 AC Mayor - Auckland Council PALINO John Independent 398 AC Mayor - Auckland Council SWARBRICK Chloe Independent 1370 AC Mayor - Auckland Council THOMAS Mark Independent 1239 AC Mayor - Auckland Council YOUNG Wayne <none> 1618 AC Albany Ward BENSCH John Independent 6130 AC Albany Ward HENETI Alezix <none> 6214 AC Albany Ward LOWE Graham Auckland Future 1389 AC Albany Ward WALKER Wayne Putting People First 688 AC Albany Ward WATSON John Putting People First 6213 AC Albany Ward WHYTE Lisa Auckland Future 1629 AC Albert-Eden-Roskill Ward CASEY Cathy City Vision 432 AC Albert-Eden-Roskill Ward FLETCHER Christine C&R - Communities & Residents 1433 AC Albert-Eden-Roskill Ward HARRIS Rob Auckland Future 2579 AC Albert-Eden-Roskill -

Waiheke Island

Waiheke Island “This is an environmentally aware community that cares deeply about protecting and cherishing the environment, the land, the water, the air”.1 “We support community-driven initiatives to reduce waste going to landfill”.2 The Waiheke Local Board vision is to create the world’s most liveable city at the local level. Its area includes Waiheke Island, Rakino Island and over ten other small islands in the Hauraki Gulf Marine Park. Rakino has its own section in this plan and the other islands are either administered by the Department of Conservation or are privately owned, with no council waste services. Waiheke Island is around 15,500 hectares3 and a 35 minute ferry ride from downtown Auckland. The following mana whenua groups claim customary and historical interests in Waiheke Island: Ngāti Paoa, Ngāti Maru, Ngāti Tai ki Tāmaki, Ngaati Whanaunga, Ngāti Tamaterā, Te Patukirikiri and Ngāti Te Ata Waiohua4. Key features of the Waiheke community are presented below. Around 8,340 permanent residents (2013 Census) 3,618 households - 30% were unoccupied at the time of the 2013 Census 66% of households are couples with children 33% one person only households Mainly European/Pakeha and Maori 90% European/pakeha, 11% Maori, 3% Pacific, 3% Asian 28% born overseas Older aged and middle income Median age 45.3, the second oldest in the Auckland region (after Great Barrier), 19% aged 65 and over $51,100 median household income, median personal income $27,200 61% employed, over 1000 local businesses, three local schools 1 Essentially Waiheke – Draft for Public Consultation, August 2016, see http://shapeauckland.co.nz/consultations/essentially-waiheke-review/. -

Local Board Information and Agreements Draft Long-Term Plan 2012-2022

DRAFT LONG-TERM PLAN 2012-2022_ VOLUME FOUR LOCAL BOARD INFORMATION AND AGREEMENTS DRAFT LONG-TERM PLAN 2012-2022_ VOLUME FOUR LOCAL BOARD INFORMATION AND AGREEMENTS About this volume About this volume This is Volume Four of the four volumes that make up the draft LTP. It is set out in two parts, one which provides background on the role of local boards, their decision-making responsibilities and some general information about local board plans and physical boundaries. The second part contains the individual local board agreements for all 21 local boards, which contain detailed information about local activities, services, projects and programmes and the corresponding budgets for the period 1 July 2012 to 30 June 2013. Here we have also included additional information like ten-year budgets for each board and a capital projects list. What this volume covers: the status of draft local board agreements how to have your say during the public consultation period an overview of the local boards local board activities information on the development of local board plans and agreements local board financial information including a consolidated statement of expenditure on local activities about each local board, with an overview of the local board including their strategic priorities and a message from the chairperson draft local board agreements for each local board covering scope of activities levels of service and performance measures local activities including key initiatives and projects expenditure and funding notes to the local board agreements contact details, how to contact your local board, including individual contact details for each local board member an appendix to each Local Board information section which includes their expenditure statements and capital projects for the ten-year period 2012 to 2022. -

Monitoring Market Research Report

Market Research Proposal Research Report Prepared for Auckland Transport Proposal Prepared For New Zealand Police May 2015 2015 Auckland Region Manual Cycle Monitor NEW ZEALAND POLICE CITIZENS’ SATISFACTION RESEARCH - Regional Summary - (TN/10/19) Presented By Gravitas Research and Strategy Ltd 26th February 2010 Gravitas Research and Strategy Limited Level 12, Wellesley Centre, 44-52 Wellesley St, Auckland PO Box 3802, Shortland St, Auckland tel. 09 356 8842, fax. 09 356 5767 e-mail. [email protected] TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 The Need For Reliable Cycle Trip Data ...................................................................................... 1 1.2 Cycle Monitoring Locations ....................................................................................................... 2 2. REGIONAL SUMMARY OF RESULTS .............................................................................................. 7 2.1 Aggregated Total ....................................................................................................................... 7 2.2 Morning Peak .......................................................................................................................... 19 2.3 Evening Peak ........................................................................................................................... 30 2.4 Annual Average Daily Traffic (AADT) Estimates ..................................................................... -

February 2021

Pub Charity Limited Declined Grants - February 2021 App Requested Approved Originating TLA Org Name App Purpose Outcome Outcome Amount Amount Code Awanui-Waipapakauri Pony Club Incorporated Equipment Maintanance $558.26 $0.00 Declined [F] 001 - Far North District Total $0.00 001 - Far North District Count 1 The Ruawai College Board of Trustees Uniforms, OTher $15,022.00 $0.00 Declined [B] Motivate Community Trust Operational Equipment $5,100.00 $0.00 Declined [A] 003 - Kaipara District Total $0.00 003 - Kaipara District Count 2 Mercury Bay Netball Incorporated Salaries and Wages $4,800.00 $0.00 Declined [C] Thames Rugby and Sports Club Incorporated Building/Facility Maintanance $11,623.00 $0.00 Declined [B] whitianga sea scout group Accommodation, OTher $271,191.36 $0.00 Declined [B] 011 - Thames-Coromandel District Total $0.00 011 - Thames-Coromandel District Count 3 Sunset Beach Lifeguard Service Incorporated Equipment Maintanance $13,830.00 $0.00 Declined [B] 013 - Waikato District Total $0.00 013 - Waikato District Count 1 Central North Island Kindergarten Trust Operational Equipment $15,000.00 $0.00 Declined [B] 019 - South Waikato District Total $0.00 019 - South Waikato District Count 1 The Whakamaru School Board of Trustees OTher $15,000.00 $0.00 Declined [B] 021 - Taupo District Total $0.00 021 - Taupo District Count 1 Waipuna Hospice Incorporated Transport $115,187.40 $0.00 Declined [A] Eastern Districts Rugby & Sports Club Incorporated Uniforms $3,690.00 $0.00 Declined [A] 022 - Western Bay of Plenty District Total $0.00 022