Light And/As Music in the History of the Color Organ Ralph Whyte Submitted

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Century of Scholarship 1881 – 2004

A Century of Scholarship 1881 – 2004 Distinguished Scholars Reception Program (Date – TBD) Preface A HUNDRED YEARS OF SCHOLARSHIP AND RESEARCH AT MARQUETTE UNIVERSITY DISTINGUISHED SCHOLARS’ RECEPTION (DATE – TBD) At today’s reception we celebrate the outstanding accomplishments, excluding scholarship and creativity of Marquette remarkable records in many non-scholarly faculty, staff and alumni throughout the pursuits. It is noted that the careers of last century, and we eagerly anticipate the some alumni have been recognized more coming century. From what you read in fully over the years through various this booklet, who can imagine the scope Alumni Association awards. and importance of the work Marquette people will do during the coming hundred Given limitations, it is likely that some years? deserving individuals have been omitted and others have incomplete or incorrect In addition, this gathering honors the citations in the program listing. Apologies recipient of the Lawrence G. Haggerty are extended to anyone whose work has Faculty Award for Research Excellence, not been properly recognized; just as as well as recognizing the prestigious prize scholarship is a work always in progress, and the man for whom it is named. so is the compilation of a list like the one Presented for the first time in the year that follows. To improve the 2000, the award has come to be regarded completeness and correctness of the as a distinguishing mark of faculty listing, you are invited to submit to the excellence in research and scholarship. Graduate School the names of individuals and titles of works and honors that have This program lists much of the published been omitted or wrongly cited so that scholarship, grant awards, and major additions and changes can be made to the honors and distinctions among database. -

UPA : Redesigning Animation

This document is downloaded from DR‑NTU (https://dr.ntu.edu.sg) Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. UPA : redesigning animation Bottini, Cinzia 2016 Bottini, C. (2016). UPA : redesigning animation. Doctoral thesis, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. https://hdl.handle.net/10356/69065 https://doi.org/10.32657/10356/69065 Downloaded on 05 Oct 2021 20:18:45 SGT UPA: REDESIGNING ANIMATION CINZIA BOTTINI SCHOOL OF ART, DESIGN AND MEDIA 2016 UPA: REDESIGNING ANIMATION CINZIA BOTTINI School of Art, Design and Media A thesis submitted to the Nanyang Technological University in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2016 “Art does not reproduce the visible; rather, it makes visible.” Paul Klee, “Creative Credo” Acknowledgments When I started my doctoral studies, I could never have imagined what a formative learning experience it would be, both professionally and personally. I owe many people a debt of gratitude for all their help throughout this long journey. I deeply thank my supervisor, Professor Heitor Capuzzo; my cosupervisor, Giannalberto Bendazzi; and Professor Vibeke Sorensen, chair of the School of Art, Design and Media at Nanyang Technological University, Singapore for showing sincere compassion and offering unwavering moral support during a personally difficult stage of this Ph.D. I am also grateful for all their suggestions, critiques and observations that guided me in this research project, as well as their dedication and patience. My gratitude goes to Tee Bosustow, who graciously -

The Journey of a Hero: Musical Evocations of the Hero's Experience in the Legend of Zelda Jillian Wyatt in Fulfillment Of

The Journey of a Hero: Musical Evocations of the Hero’s Experience in The Legend of Zelda Jillian Wyatt In fulfillment of M.M. in Music Theory Supervised by Dr. Benjamin Graf, Dr Graham Hunt, and Micah Hayes May 2019 The University of Texas at Arlington ii ABSTRACT Jillian Wyatt: The Journey of a Hero Musical Evocations of the Hero’s Experience in The Legend of Zelda Under the supervision of Dr. Graham Hunt The research in this study explores concepts in the music from select games in The Legend of Zelda franchise. The paper utilizes topic theory and Schenkerian analysis to form connections between concepts such as adventure in the overworld, the fight or flight response in an enemy encounter, lament at the loss of a companion, and heroism by overcoming evil. This thesis identifies and discusses how Koji Kondo’s compositions evoke these concepts, and briefly questions the reasoning. The musical excerpts consist of (but are not limited to): The Great Sea (Windwaker; adventure), Ganondorf Battle (Ocarina of Time; fight or flight), Midna’s Lament (Twilight Princess; lament), and Hyrule Field (Twilight Princess; heroism). The article aims to encourage readers to explore music of different genres and acknowledge that conventional analysis tools prove useful to video game music. Additionally, the results in this study find patterns in Koji Kondo’s work such as (to identify a select few) modal mixture, military topic, and lament bass to perpetuate an in-game concept. The most significant aspect of this study suggests that the music in The Legend of Zelda reflects in-game ideas and pushes a musical concept to correspond with what happens on screen while in gameplay. -

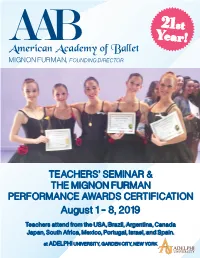

The Mignon Furman Performance Awards 1000S of Dancers!

21st AAB Year! American Academy of Ballet MIGNON FURMAN, FOUNDING DIRECTOR TEACHERS’ SEMINAR & THE MIGNON FUR MAN PERFORMANCE AWARDS CERTIFICATION August 1 – 8, 2019 Teachers attend from the USA, Brazil, Argentina, Canada Japan, South Africa, Mexico, Portugal, Israel, and Spain. at ADELPHI UNIVERSITY, GARDEN CITY, NEW YORK REASONS TO ATTEND THE SEMINAR Mignon Furman 10 AND THE PERFORMANCE AWARDS Founder of the AAB, Teacher, Choreographer, Educationist. CERTIFICATION EVERYTHING MOVES FORWARD. “ THEREFORE, I RECOMMEND: ith her talents, courage, and determination KEEP IN TOUCH WITH YOUR ART. to give definition to her vision for ballet PERFORMANCE AWARDS — AGRIPPINA VAGANOVA, ” Weducation, Mignon Furman founded the American and “Steps” programs. Most wonderful programs for “BASIC PRINCIPLES OF CLASSICAL BALLET” (1934) Academy of Ballet: It soon became the premier teachers and their dancers. (View the brochures on Summer School in the United States. our website.) he composed the Performance Awards S which are taught all over the USA, and are an CERTIFICATION : international phenomenon, praised by teachers Become a certified Performance Awards teacher. in the USA and in many other countries. The Hang your diploma in your studio. success of the Performance Awards is due to Mignon’s choreography: She was a superb choreographer. Her many compositions are FOUR DANCES : free of cliché. They have logic, harmony, style, To teach in your school. (See page 5.) and intrinsic beauty. OBSERVE : Our distinguished argot Fonteyn, a friend of Mignon, gave faculty teaching our Summer School dancers. her invaluable advice, during several You have the option of taking the classes. Mdiscussions about the technical, and artistic aspects of classical ballet. -

Debugging Color Organs

HauntMaven.com - Wolfstone's Haunted Halloween Site http://wolfstone.halloweenhost.com/ColorOrgans/clofix_DebuggingColorOrgans.html#OptocouplerBasedColorOrgans Debugging Color Organs Elsewhere on our web site, we discuss the theory and application of color organs. We also discuss the availability of commercial color organs and kits. This page is dedicated to what can go wrong with a color organ. CAUTION Little battery‐operated color organs that flash LEDs in time to the sound picked up from a microphone are relatively safe to work on. The worst you can do is destroy your project, of burn yourself on your soldering iron. But any color organ that plugs into the wall deals with hazardous voltages. If you aren't prepared to know and follow high-voltage precautions, you shouldn't be poking around in a line-operated appliance! Obtained from Omarshauntedtrail.com Preliminary Examination Before you start screwing around with the gadget, take a moment to look it over closely. • Is it physically damaged? Cracked case or busted parts? Waterlogged? • Is it plugged in and turned on? • Does the pilot light come on? • Is the fuse OK? • Are the lamps plugged in to it? • Have you tested the lamps to make sure they work? For testing color organs, I have found it handy to get a set of small, identical incandescent lamps. Small night-lights from your local discount store would be fine. Plug them all in, power up the color organ, and see if some of the channels work and others do not. You Need A Schematic For any repair that is not utterly trivial, you will need a schematic diagram. -

An Analysis of Honegger's Cello Concerto

AN ANALYSIS OF HONEGGER’S CELLO CONCERTO (1929): A RETURN TO SIMPLICITY? Denika Lam Kleinmann, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2014 APPROVED: Eugene Osadchy, Major Professor Clay Couturiaux, Minor Professor David Schwarz, Committee Member Daniel Arthurs, Committee Member John Holt, Chair of the Division of Instrumental Studies James Scott, Dean of the School of Music Mark Wardell, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Kleinmann, Denika Lam. An Analysis of Honegger’s Cello Concerto (1929): A Return to Simplicity? Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2014, 58 pp., 3 tables, 28 examples, 33 references, 15 titles. Literature available on Honegger’s Cello Concerto suggests this concerto is often considered as a composition that resonates with Les Six traditions. While reflecting currents of Les Six, the Cello Concerto also features departures from Erik Satie’s and Jean Cocteau’s ideal for French composers to return to simplicity. Both characteristics of and departures from Les Six examined in this concerto include metric organization, thematic and rhythmic development, melodic wedge shapes, contrapuntal techniques, simplicity in orchestration, diatonicism, the use of humor, jazz influences, and other unique performance techniques. Copyright 2014 by Denika Lam Kleinmann ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF TABLES………………………………………………………………………………..iv LIST OF MUSICAL EXAMPLES………………………………………………………………..v CHAPTER I: INTRODUCTION………..………………………………………………………...1 CHAPTER II: HONEGGER’S -

Michele Leigh Paper : Animated Music

GA2012 – XV Generative Art Conference Michele Leigh Paper : Animated Music: Early Experiments with Generative Art Abstract: This paper will explore the historical underpinnings of early abstract animation, more particularly attempts at visual representations of music. In order to set the stage for a discussion of the animated musical form, I will briefly draw connections to futurist experiments in art, which strove to represent both movement and music (Wassily Kandinsky for instance), as a means of illustrating a more explicit desire in animation to extend the boundaries of the art in terms of materials and/or techniques By highlighting the work of experimental animators like Hans Richter, Oskar Fishinger, and Mary Ellen Bute, this paper will map the historical connection between musical and animation as an early form of generative art. I will unpack the ways in which these filmmakers were creating open texts that challenged the viewer to participate in the creation of meaning and thus functioned as proto-generative art. Topic: Animation Finally, I will discuss the networked visual-music performances of Vibeke Sorenson as an artist who bridges the experimental animation Authors: tradition, started by Richter and Bute, and contemporary generative art Michele Leigh, practices. Department of Cinema & Photography This paper will lay the foundation for our understanding of the Southern Illinois history/histories of generative arts practice. University Carbondale www.siu.edu You can send this abstract with 2 files (.doc and .pdf file) to [email protected] or send them directly to the Chair of GA conferences [email protected] References: [1] Paul Wells, “Understanding Animation,” Routledge, New York, 1998. -

December 1940) James Francis Cooke

Gardner-Webb University Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 John R. Dover Memorial Library 12-1940 Volume 58, Number 12 (December 1940) James Francis Cooke Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude Part of the Composition Commons, Ethnomusicology Commons, Music Education Commons, Musicology Commons, Music Pedagogy Commons, Music Performance Commons, Music Practice Commons, and the Music Theory Commons Recommended Citation Cooke, James Francis. "Volume 58, Number 12 (December 1940)." , (1940). https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude/59 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the John R. Dover Memorial Library at Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. —— THE ETUDE Price 25 Cents mueie magazine i — ' — ; — i——— : ^ as&s&2i&&i£'!%i£''££. £&. IIEHBI^H JDiauo albums fcj m Christmas flarpms for JfluStc Jfolk IS Cljiistmas iSnraaiitS— UNTIL DECEMBER 31, 1940 ONLY) (POSTPAID PRICES GOOD CONSOLE A Collection Ixecttalist# STANDARD HISTORY OF AT THE — for £111 from Pegtnner# to CHILD’S OWN BOOK OF of Transcriptions from the Masters Revised Edition PlAVUMfl MUSIC—Latest, GREAT MUSICIANS for the Pipe Organ or Electronic DECEMBER 31, 1940 By James Francis Cooke Type of Organ Compiled and MYllfisSiiQS'K PRICES ARE IN EFFECT ONLY UP TO By Thomas -

Technique: Battement Tendu Once Upon a Ballet™

Technique: Battement Tendu Once Upon A Ballet™ Tendus are done during “circle barre” or “centre barre” up through Pre-Ballet II. In Ballet 1, students begin performing tendus at the barre. RECOMMENDED PROGRESSION OF BATTEMENT TENDU: ● 2 year olds should be able to “tendu” with the help of a prop (such as a bean bag, mat or tape for them to point to with their toes). They may also need the help of a parent/caregiver. ● 3 year olds should be able to tendu to the front in parallel with correct posture. ● 4 years olds should be able to tendu to the front from a "slight V" 1st position with correct posture. ● 5 and 6 year olds should tendu front and side from a "natural" 1st position with correct posture. Students should be introduced to completing tendus at varying speeds. When done slowly, there should be emphasis placed on rolling through the demi pointe to close. ● 7 through 9 year olds should tendu to the front, side and back from 1st position. Tendus should be introduced in a slow tempo with emphasis placed on rolling through the demi pointe. Later in the year, students should also be introduced to tendu front, side and back from 5th position. AGE-APPROPRIATE IMAGES AND WORDS TO USE: ● To help students work through their feet correctly, use the word “slide” out and “slide” in for tendus. ● If telling your students to “straighten” their knees does not obtain results, try telling them to “stretch their legs long” or to “keep their knees stiff”. Sometimes using different language will click better with certain students. -

Ballet Terms Definition

Fundamentals of Ballet, Dance 10AB, Professor Sheree King BALLET TERMS DEFINITION A la seconde One of eight directions of the body, in which the foot is placed in second position and the arms are outstretched to second position. (ah la suh-GAWND) A Terre Literally the Earth. The leg is in contact with the floor. Arabesque One of the basic poses in ballet. It is a position of the body, in profile, supported on one leg, with the other leg extended behind and at right angles to it, and the arms held in various harmonious positions creating the longest possible line along the body. Attitude A pose on one leg with the other lifted in back, the knee bent at an angle of ninety degrees and well turned out so that the knee is higher than the foot. The arm on the side of the raised leg is held over the held in a curved position while the other arm is extended to the side (ah-tee-TEWD) Adagio A French word meaning at ease or leisure. In dancing, its main meaning is series of exercises following the center practice, consisting of a succession of slow and graceful movements. (ah-DAHZ-EO) Allegro Fast or quick. Center floor allegro variations incorporate small and large jumps. Allonge´ Extended, outstretched. As for example, in arabesque allongé. Assemble´ Assembled or joined together. A step in which the working foot slides well along the ground before being swept into the air. As the foot goes into the air the dancer pushes off the floor with the supporting leg, extending the toes. -

Consonance and Dissonance in Visual Music Bill Alves Harvey Mudd College

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont All HMC Faculty Publications and Research HMC Faculty Scholarship 8-1-2012 Consonance and Dissonance in Visual Music Bill Alves Harvey Mudd College Recommended Citation Bill Alves (2012). Consonance and Dissonance in Visual Music. Organised Sound, 17, pp 114-119 doi:10.1017/ S1355771812000039 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the HMC Faculty Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in All HMC Faculty Publications and Research by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Organised Sound http://journals.cambridge.org/OSO Additional services for Organised Sound: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here Consonance and Dissonance in Visual Music Bill Alves Organised Sound / Volume 17 / Issue 02 / August 2012, pp 114 - 119 DOI: 10.1017/S1355771812000039, Published online: 19 July 2012 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S1355771812000039 How to cite this article: Bill Alves (2012). Consonance and Dissonance in Visual Music. Organised Sound, 17, pp 114-119 doi:10.1017/ S1355771812000039 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/OSO, IP address: 134.173.130.244 on 24 Jul 2014 Consonance and Dissonance in Visual Music BILL ALVES Harvey Mudd College, The Claremont Colleges, 301 Platt Blvd, Claremont CA 91711 USA E-mail: [email protected] The concepts of consonance and dissonance broadly Plato found the harmony of the world in the Pythag- understood can provide structural models for creators of orean whole numbers and their ratios, abstract ideals visual music. -

Give Me Something to Sing About": Intertextuality and the Audience in "Once More, with Feeling"

Chapter 12 "Give Me Something to Sing About": Intertextuality and the Audience in "Once More, with Feeling" Amy Bauer "I love all musicals." (Joss Whedon, audio commentary to "Once More, with Feeling.") Critics hailed "Once More, with Feeling" (6.7) as a brilliant example of the television musical. Its musical numbers flow from the narrative, yet prove integral to the seven-year arc of the series, and its eclectic but unified score was written expressly for the talents of a cast (mostly) new to the genre. Notably, its book, score, and concept all sprang from one mind, that of the Buffyverse's primary architect, Joss Whedon. Although untrained in musical composition, Whedon's affection for and knowledge of the American musical are everywhere evident, even if we did not have John Kenneth Muir's admission that he is a "virtual encyclopedia of musical film history."1 Analogous to the combined cinematic genres-from horror to religious epic-that mark Buf/Y the Vampire Slayer and Angel, "Once More, with Feeling" alludes to Sondheim and Loesser alongside the sardonic charm of 1940s music, 1950s swing jazz, 1970s arena rock, 1980s power ballads, and 1990s soft-rock confessionals, all within a lean, swift-moving structure that performs the dramatic functions of the classic American musical. Much has already been written regarding the novelty, influence, and intertextual richness of the Buf/Y musical.2 My contribution to that literature analyzes the musical structure of the songs themselves and places it in a dialogic relationship to the sources they summon. Such intertextual richness acknowledges fans' devotion to and knowledge of both the show's history and cultural references to the John Kenneth Muir, Singing a New Tune: The Rebirth ofthe Modern Film Musical, from Evita to De-Lovely and Beyond (New York, 2005), p.