Dispute Resolution in Irish Sport: the Courts As Reluctant Interlopers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

October 2019 Monthly Management Report

DUN LAOGHAIRE RATHDOWN OCTOBER MONTHLY MANAGEMENT REPORT 1ST October – 31st October 2019 1 | P a g e CONTENT DIRECTORATES CORPORATE, COMMUNICATIONS, GOVERNANCE AND TOURISM Page 3 Director: Mary T. Daly MUNICIPAL SERVICES Page 6 Deputy Chief Executive and Director: Tom McHugh FINANCE AND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT Page 17 Director: Helena Cunningham HOUSING* See note below Director: Catherine Keenan PLANNING Page 20 Director: Mary Henchy FORWARD PLANNING INFRASTRUCTURE * See note below Director: Anne Devine INFRASTRUCTURE AND CLIMATE CHANGE Page 21 A/Director: Mick Mangan ARCHITECTS Page 22 County Architect: Andree Dargan COMMUNITY AND CULTURAL DEVELOPMENT Page 23 Director: Dearbhla Lawson DUN LAOGHAIRE HARBOUR Page 28 A/Director: Therese Langan *Included in Quarterly Management Report 2 | P a g e Corporate, Communications, Governance & Tourism Cases logged in October 2019 Cases Logged by Status, October 2019 752 Active Inactive 2511 Open 752 Closed 2511 Cases Logged in October 2019, by Section: Section/Dept. Open Closed Total Architects 3 3 6 Ballyogan Depot 8 2 10 CoCo Markets 4 8 12 Communications & Civic Hub 21 913 934 Community 3 6 9 Corporate Services 6 6 Environment 221 543 764 Finance 67 319 386 Housing 17 162 179 Parks 176 117 293 Planning 4 15 19 Property 3 8 11 Transportation 200 349 549 Waste Enforcement 16 53 69 Water Services 3 13 16 Grand Total 752 2511 3263 3 | P a g e Civic Hub Activities: Cases logged in October 2019 Civic Hub Interactions, October 2019* 1,938 594 Info@ 443 Tempreps@ Counter Interactions Phones* 9,889 * Pie -

Irish Injured Jockeys Fund Claiming Race Gowran Park Wednesday 11Th August 2021

Irish Stallion Farms EBF Claiming Race Fairyhouse Monday 20th September 2021 Claims received: Claimant: Horse: Price: Designated Trainer: No Claims DundalkStadium.com Claiming Race Dundalk Thursday 2nd September 2021 Claims received: Claimant: Horse: Price: Designated Trainer: Noel C. Kelly Sister Lola €8,000 Noel C. Kelly Edward Lynam Sister Lola €8,000 Edward Lynam Ms. Aileen Lynam Sister Lola €8,000 Sarah Lynam James McAuley Sister Lola €8,000 James McAuley James McAuley Beleaguerment €6,000 James McAuley John Andrew Kinsella Sister Lola €8,000 John Andrew Kinsella Alotdonemoretodo Sister Lola €8,000 M.C. Grassick Syndicate Tony Beegan Sister Lola €8,000 Paul W. Flynn John C. McConnell Sister Lola €8,000 John C. McConnell R F O’Brien Racing Club Sister Lola €8,000 John Andrew Kinsella Mrs. Sinead Kelly Sister Lola €8,000 Muredach Kelly Thomas W. McGrath Sister Lola €8,000 Muredach Kelly Successful claims: Claimant: Horse: Price: Designated Trainer: James McAuley Sister Lola €8,000 James McAuley James McAuley Beleaguerment €6,000 James McAuley Golf At Gowran Park Claiming Race Gowran Park Wednesday 1st September 2021 Claims received: Claimant: Horse: Price: Designated Trainer: No Claims Irish Stallion Farms EBF Claiming Maiden Tipperary Thursday 26th August 2021 Claims received: Claimant: Horse: Price: Designated Trainer: John M. Keogh Don Julio €15,000 S.M Duffy B.A. Murphy Don Julio €15,000 B.A. Murphy Mrs. H. O’Toole Don Julio €15,000 Thomas Cleary Successful claims: Claimant: Horse: Price: Designated Trainer: John M. Keogh Don Julio €15,000 S.M. Duffy Irish Injured Jockeys Fund Claiming Race Gowran Park Wednesday 11th August 2021 Claims received: Claimant: Horse: Price: Designated Trainer: P. -

Monthly Management Report June 2021

DÚN LAOGHAIRE RATHDOWN JUNE MONTHLY MANAGEMENT REPORT 1 June – 24 June 2021 1 | P a g e COVID-19 While there was further easing of restrictions during June, they did not impact on many of our services, with the exception of gyms and swimming pools reopening for individual training. Numbers permitted at outdoor organised events also increased. As the public health advice continued to recommend that staff continue to work from home were possible. Staff continued to work remotely were possible while access to County Hall by members of the public is by appointment only, for urgent business. Updates on services affected, by department are detailed below: Libraries All dlr Library spaces re-opened to the public on Monday 10 May. This is part of a gradual, responsible resumption of onsite library services in line with Government guidelines. Services available during this phase include: Return and borrowing of items, quick browse visits with restricted numbers in place and a return to usual staffed opening hours with late evenings and Saturday opening. Printing from home, from a personal device, or from a designated quick-use PC and use of self-service photocopiers resumed while use of Surfbox postal printing service, for next day delivery, and the availability of all our online services continued. The national reserves system was also re-instated during this phase as was the national delivery service for inter-county reservations. However, as per Government guidelines for this phase, we are unable at present to provide any service which involves seating, including general seating or study spaces. We are unable at this time to provide full access to Internet PCs/laptops, or to programme live indoor events in our spaces. -

Quarter Finals

LEINSTER GAA Senior FOOTBALL Championship 2020 QUARTER FINALS 7.11.2020 WESTMEATH V DUBLIN 6.15pm MW Hire O’Moore Park 8.11.2020 WICKLOW V MEATH 1.30pm Aughrim LONGFORD V LAOIS 1.30pm Glennon Brothers Pearse Park OFFALY V KILDARE 5.30pm MW Hire O’Moore Park RUNAÍ CLÁR OIFIGIÚIL The stands may be silent but LEINSTER GAA Senior FOOTBALL Championship 2020 we know our communities are WESTMEATH v DUBLIN 7:11:2020 standing tall behind us. 6.15pm MW Hire O’Moore Park MATCH OFFICIALS Referee: Martin McNally (Muineachán) Std By: Joe McQuillan An Cabhán) Linesman: Brendan Cawley (Cill Dara) Sideline: James Molloy (Gaillimh) Umpires: Ben Woods, Dylan Finnegan, Mark Gilsenan, Anthony Marron LONGFORD V LAOIS 8:11:2020 1.30pm Glennon Brothers Pearse Park MATCH OFFICIALS Referee: Sean Hurson (Tír Eoghan) Std By: Brendan Cawley (Cill Dara) Linesman: Sean Laverty (Antroim) Sideline: Fergal Smyth Uibh Fhailaí) Umpires: Martin Coney, Mel Taggart ,Cathal Forbes, Martin Conway OFFALY V KILDARE 8:11:2020 5.30pm MW Hire O’Moore Park MATCH OFFICIALS Help us make your SuperFan voice heard by sharing a video of Referee: David Coldrick (An Mhí) Std By: Conor Lane (Corcaigh) how you Support Where You’re From on: Linesman: Anthony Nolan(Cill Mhaintáin) Sideline: Patrick Maguire (Longfort) Umpires: Padraig Coyle, Pat Darby, Stephen O’Hare, Ronan Garry @supervalu_irl @SuperValuIreland using the #SuperValuSuperFans WICKLOW V MEATH 8:11:2020 1.30pm Aughrim MATCH OFFICIALS Referee: Ciaran Branagan ( An Dún) Std By: Martin McNally (Muineachán) Linesman: John Hickey (Ceatharlach) SUPPORT Sideline: David Hickey(Ceatharlach) Where You’re From Umpires: Mickey Curran, Conor Curran, Marty Brady, Seamie O Hanlon FA I LT E O N SPONSORS gCathaoirleach MESSAGE Fáilte Róimh Go Léir inniu, With last weekend behind us we all look with Longford, Wicklow and Offaly will be buoyed by anticpation to our Leinster GAA Senior Football their opening Round victories and will be hoping Quarter Finals. -

Grid Export Data

Sports Capital and Equipment Programme all organisations registered March 2021 Organisation Name County 4th Carlow Leighlinbrige Scout Group Carlow All Star Sporting and Recreation Ltd Carlow Ardattin Athletic Club Carlow Asca GFC Carlow Askea Karate CLub Carlow Askea Sports Ltd Carlow Bagenalstown AFC Carlow BAGENALSTOWN ATHLETIC CLUB Carlow Bagenalstown Community Games Carlow Bagenalstown Cricket Club Carlow Bagenalstown Family Resource Centre Ltd Carlow Bagenalstown Karate Club Carlow Bagenalstown Pitch & Putt Club Carlow Bagenalstown Swimming Club Carlow Ballinabranna GAA Club Carlow Ballinkillen Hurling Club Carlow Ballinkillen Lorum Community Centre Club Carlow Ballon GAA Club Carlow Ballon Hall Committee Limited Carlow Ballon Karate Club Carlow Ballymurphy Celtic AFC Carlow Ballymurphy Hall Ltd Carlow Ballymurphy Indoor Soccer Club Carlow Barrow Valley Riding Club Carlow Bennekerry N.S Carlow Bigstone Community Centre Carlow Borris Golf Club Carlow Borris Tidy Towns Association Ltd Carlow Borris/St. Mullins Community Games Carlow Burrin Celtic F.C. Carlow Carlow & District Juveniles League Carlow Carlow Basketball Club Carlow Carlow Carsports Club CLG Carlow CARLOW COUNTY COUNCIL Carlow Carlow Cricket Club Carlow Carlow Dragon Boat Club Carlow Carlow Golf Club Carlow Carlow Gymnastics Club Carlow Carlow Hockey Club Carlow Carlow Karate Club Carlow Carlow Kickboxing Club Carlow Carlow Lawn Tennis Club Carlow Carlow Road Cycling Club Carlow Carlow Rowing Club Carlow Carlow Scot's Church Carlow Carlow Special Olympics Club Carlow Carlow -

County by County Breakdown 2021.Xlsx

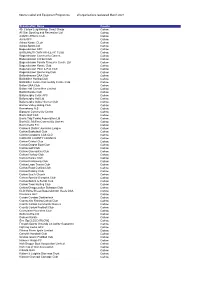

Intel Matching Grant Organisations – 2021 ORGANISATION COUNTY St Patricks Gaelic Athletic Club, Dromintee Armagh Clonegal National School Carlow County Carlow Football Club Carlow Gaelscoile Eoghain Ui Thuairisc Carlow Killeshin FC Carlow Palatine GAA Club Carlow Rathvilly Juvenile GAA Club Carlow Scoil Mhuire gan Smal Carlow Setanta GAA Ceatharlach Carlow Slaney Rovers AFC Carlow St Patrick's National School Carlow Tullow RFC Carlow Ballyhaise GAA Club Cavan Castletara N.S. Cavan Kill National School Cavan Kill Shamrocks GAA Cavan Munterconnaught Gaelic Football Club Cavan Banner GAA Club Clare Barefield National School Clare Fergus Rovers Ladies Football Club Clare Scariff Central NS Clare Scariff GAA Club Clare St Joseph's Doora Barefield GAA Club Clare Bishopstown GAA Club Cork Cork Samaritans Cork Douglas Hall AFC Cork Feileacain Teoranta Cork Irish Guide Dogs for the Blind Cork Rockban Ladies Football - Camogie Club Cork Robert Emmets GAA club Donegal Sn Naomh Samhthann Donegal 11th Meath Kilcloon Scout Group via Scouting Ireland Dublin 1st 10th Kildare Leixlip Scout Group via Scouting Ireland Dublin 1st Kildare, 2nd Celbridge Scout Group via Scouting Ireland Dublin 20th Meath (Stamullen) via Scouting Ireland Dublin 22nd Kildare Scout Group via Scouting Ireland Dublin 24th Kildare Carbury Scout Group via Scouting Ireland Dublin 8th Kildare Scout Group (Maynooth) via Scouting Ireland Dublin ALONE Dublin Amnesty International Ireland Dublin An Taisce-National Trust For Ireland. Dublin Aoibheanns Pink Tie Dublin Ashbourne United Football -

Border (Cavan/Monaghan/ Louth)

BORDER (CAVAN/MONAGHAN/ LOUTH) THE ECONOMIC IMPACT OF BREEDING AND RACING IN YOUR REGION CONTENTS FOREWORD 04 REGIONAL ANALYSIS 06 THE ECONOMIC IMPACT 15 OF ONE RACEHORSE ECONOMIC IMPACT OF 17 BREEDING AND RACING IN IRELAND SUCCESS OF IRISH 20 BREEDING AND RACING REPORT PREPARATION 22 METHODOLOGY AND LIMITATIONS 2 HORSE RACING IRELAND ECONOMIC IMPACT STUDY: BORDER DERRY BORDER DONEGAL ANTRIM (CAVAN/MONAGHAN/LOUTH) TYRONE FERMANAGH ARMAGH DOWN REGIONAL SUMMARY SLIGO MONAGHAN LEITRIM 450 Direct, indirect CAVAN DUNDALK and secondary MAYO LOUTH ROSCOMMON employment LONGFORD 49,998 Attendees MEATH at racing WESTMEATH DUBLIN €25m Total direct and GALWAY stimulated OFFALY expenditure KILDARE LAOIS WICKLOW CLARE CARLOW TIPPERARY KILKENNY LIMERICK WEXFORD KERRY WATERFORD CORK Racecourses HORSE RACING IRELAND ECONOMIC IMPACT STUDY: BORDER 3 FOREWORD BREEDING AND RACING ENJOYS A RICH TRADITION OF SUCCESS IN THE BORDER. AS WELL AS SUCCESS ON THE TRACK AND IN THE BREEDING SHEDS, THE INDUSTRY PROVIDES AROUND 450 JOBS AND €25m IN ANNUAL EXPENDITURE. THE BORDER COUNTIES ALSO HOST IRELAND’S FIRST ALL-WEATHER TRACK IN DUNDALK, WHICH PLAYS A KEY ROLE IN THE NATIONAL FIXTURE LIST. 4 HORSE RACING IRELAND ECONOMIC IMPACT STUDY: BORDER BORDER It is a great privilege to introduce Deloitte’s Deloitte estimate in this new report that This document first provides a specific Economic Impact Study into the Breeding and Breeding and Racing is an integral part of overview of the contribution of horseracing Racing Industry in the Border counties, for the rural economy of the Border counties, to the counties of Cavan, Monaghan the first time capturing the contribution this contributing around 450 jobs in direct, indirect and Louth. -

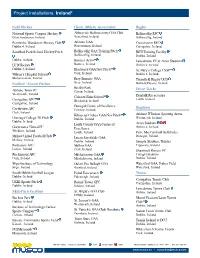

Project Installations: Ireland*

Project Installations: Ireland* Field Hockey Gaelic Athletic Association Rugby National Sports Campus Hockey Abbeyside Ballinacourty GAA Club Ballincollig RFC Blanchardstown, Ireland Waterford, Ireland Ballincollig, Ireland Pembroke Wanderers Hockey Club Athlone GAA Crosshaven RFC Dublin 4, Ireland Roscommon, Ireland Carrigaline, Ireland Sandford Park School Hockey Pitch Ballincollig GAA Training Pitch IRFU Training Facility Ballincollig, Ireland Dublin, Ireland Dublin, Ireland Banteer Astro** Lansdowne FC at Aviva Stadium UCD Hockey Banteer, Ireland Dublin 4, Ireland Dublin 4, Ireland Blackrock GAA New Pitch** St. Mary’s College CSSP** Wilson’s Hospital School Cork, Ireland Dublin 6, Ireland Multyfarnham, Ireland Bray Emmets GAA Thornfield Rugby UCD Bray, Ireland Belfield Downs, Ireland Football / Soccer Pitches Breffni Park Horse Tracks Athlone Town FC Cavan, Ireland Westmeath, Ireland Colaiste Eoin School** Dundalk Racecourse Carrigaline AFC** Blackrock, Ireland Louth, Ireland Carrigaline, Ireland Donegal Centre of Excellence Stadiums Castleview AFC Convoy, Ireland Cork, Ireland Kilmacud Crokes GAA New Pitch** Athl one IT Indoor Sporting Arena Gonzaga College 3G Pitch Dublin, Ireland Westmeath, Ireland Dublin, Ireland Louth County GAA Centre of Aviva Stadium Greystones United FC Excellence Dublin 4, Ireland Wicklow, Ireland Louth, Ireland Pairc MacCumhaill Ballybofey Mallow United Football Club Lucan Sarsfields GAA Donegal, Ireland Mallow, Ireland Dublin, Ireland Semple Stadium, Thurles Portlaoise AFC Mallow GAA Tipperary, Ireland Laoise, Ireland Cork, Ireland Shamrock Rovers FC Rockmount AFC Mitchelstown GAA Tallaght Stadium Cork, Ireland Mitchelstown, Ireland Dublin, Ireland Sligo Institute of Technology Oulart The Ballagh GAA Waterford GAA, Fraher Field Sligo, Ireland Wexford, Ireland Waterford, Ireland South Dublin Football League Pobal Eascarrach Tennis Dublin, Ireland Falcarragh, Ireland Carrigaline Tennis Club UKBL Sports Pitch Round Tower GFC Carrigaline, Ireland Dublin, Ireland Kildare, Ireland Lansdowne Tennis Club Multi-Pitch Facilities St. -

GAA Healthy Club Project

List of Phase 2 Participating Clubs * Indicates that club also participated in Phase 1 Club Name County Province Mount Leinster Rangers GAA Club Carlow Leinster Clara GAA Club Kilkenny Leinster Dromard GAA Club Longford Leinster Castletown Liam Mellows GAA Club Wexford Leinster St. John’s Volunteers GAA Club* Wexford Leinster St. Kevin’s GAA Club Louth Leinster Bray Emmets GAA Club Wicklow Leinster Annacurra GAA Club* Wicklow Leinster St. Loman’s Mullingar GAA Club Westmeath Leinster Ballynacgary GAA Club Westmeath Leinster Tubber GAA Club Offaly Leinster Clonad GAA Club Laois Leinster Kilmacud Crokes GAA Club Dublin Leinster Raheny GAA Club Dublin Leinster Good Counsel GAA Club Dublin Leinster Craobh Chiarain GAA Club Dublin Leinster Thomas Davis GAA Club* Dublin Leinster Castlemitchell GAA Club Kildare Leinster Kiltale GAA Club Meath Leinster St. Colmcille’s GAA Club* Meath Leinster Club Name County Province Killeagh GAA Club Cork Munster Castlehaven GAA Club Cork Munster St. Finbarr’s Hurling & Football Club* Cork Munster Midleton GAA Club* Cork Munster JK Bracken’s GAA Club Tipperary Munster Fr. Sheehy GAA Club Tipperary Munster Nenagh Éire Óg GAA Club* Tipperary Munster Na Piarsaigh GAA Club Limerick Munster Mungret’s St. Pauls GAA Club* Limerick Munster Parteen GAA Club Clare Munster Tralee Parnell’s Hurling Club Kerry Munster Beautfort GAA Club* Kerry Munster Brickey Rangers Waterford Munster 1 Club Name County Province An Cáislean Glas Cumann Naomh Padraig GAA Club Tyrone Ulster Omagh, St. Enda's GAA Club Tyrone Ulster Gaeil Truicha (Emyvale) GAA Club Monaghan Ulster St. Tiernach's, Clones GAA Club Monaghan Ulster Castleblayney Faughs GAA Club* Monaghan Ulster Derrygonnelly Harps GAA Club Fermanagh Ulster Erne Gaels GAC Belleek GAA Club Fermanagh Ulster Cumann Chluain Daimh (Clonduff) GAA Club Down Ulster St. -

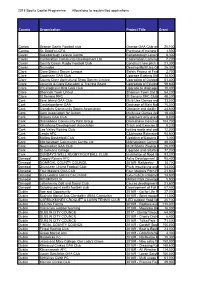

Grid Export Data

2018 Sports Capital Programme Allocations to resubmitted applications County Organisation Project Title Grant Carlow Grange Gaelic Football club Grange GAA Club and Grounds25,100 Refurbishment Carlow St. Brigid's LGFA Purchase of training and storage1,500 equipment. Cavan Bailieborough Leisure Centre Bailieborough Leisure Centre8,300 refurbishment Cavan Castlerahan Community Development Ltd Castlerahan Community Development7,200 Ltd Cavan County Cavan Rugby Football Club Construct new pitch 21,300 Cavan Drumalee Develop Multi Use Games26,300 Area & Community Walkway Clare Clare District Soccer League Safety Project at Frank Healy2,700 Park Clare Coolmeen GAA Club Upgrade Existing Shower 14,500Facilities/ Dressing Rooms Clare County Clare Agricultural Show Society Limited Upgrading of Outdoor and51,800 Indoor Showjumping Arena Clare Limerick & Clare Education & Training Board Upgrading of Existing Athletics59,600 Track Clare O'Callaghans Mills GAA Club Upgrade to drainage in our10,400 pitch in OCMills Clare Shannon Town United Shannon Town Utd Dressing54,200 Rooms Construction Clare St Senans RFC St Senans RFC Club House48,200 expansion. Cork Bere Island GAA Club Multi Use Games area for33,000 Bere Island Cork Castletownbere GAA Drainage of Main Natural 75,000Pitch Cork Clonakilty Community Sports Association Obstacle and Agility Course24,600 for 4 - 12 year olds Cork Cork Association for Autism Multi-Use Games Area Installation18,400 Cork Dripsey GAA Club Equipment only grant Application8,000 Cork Dromahane Community Park Group Dromahane -

Local History Review Vol

Local History Review Vol. 18, 2013 Federation of Local History Societies Conascadh na gCumann Staire Aitiula LOCAL HISTORY REVIEW 2013 Local History Review Vol. 18, 2013 Federation of Local History Societies Conascadh na gCumann Staire Aitiula Larry Breen, Hon. Editor i LOCAL HISTORY REVIEW 2013 Local History Review 2013 © Federation of Local History Societies 2013 Cover illustration: Reginald’s Tower, Waterford. Photograph: Larry Breen Published by Federation of Local History Societies Typesetting and Design J. J. Woods Printed by Naas Printing Ltd., Naas, Co. Kildare ii LOCAL HISTORY REVIEW 2013 Contents Page The Federation of Local History Societies v Federation Officers/Committee 2012-2013 vii Editorial ix Articles Arthur Young’s — A Tour of Ireland, 1776-1779, Denis Marnane, Tipperary County Historical Society 01 The Drumm Battery Railcars, 1932-1949, James Scannell, Old Dublin Society 11 From Dublin to Strabane, An Irish Doctor’s Travels in 1810, Johnny Dooher, Strabane, Federation for Ulster Local Studies 21 The Hunt/De Vere family and some descendants, Jim Heffernan, Clane Local History Group 28 Talking About — “Talking About History”, Padraig Laffan, Foxrock History Club 41 Verda Fjord, Urbs Intacta, Crystal City, Julian Walton, Resident Historian, Dunhill Enterprise Centre, Co. Waterford 47 The Cantillons and Crosbies of Ballyheigue, Co. Kerry, Bryan MacMahon, Kerry Archaeological Society 60 Naas Ancient and Modern, Paddy Behan, Naas Local History Group 66 From Village to Resort, From Town to Suburb. Clontarf since 1760, Claire Gogarty, Clontarf Historical Society 74 A Cautionary Tail, Alan Counihan, Artist/Writer, Kilkenny 80 The Sharkey Sisters, Strokestown, Edward J. Law, Kilkenny Archaeological Society 92 Colonel Fiach “Luke O’Toole”, the Eleven Years War and All That, Cathal Mac Oireachtaigh, Roundwood and District Hist. -

June 2020 Monthly Management Report

DUN LAOGHAIRE RATHDOWN JUNE MONTHLY MANAGEMENT REPORT 1 June – 25 June 2020 1 | P a g e COVID-19 In line with the Government Roadmap for Reopening Society & Business, the council commenced a phased return to work in line with the easing of restrictions. The Business Continuity Team are co-ordinating this phased return. The Council continues to work with businesses to support them, with restart grants, licencing of outdoor tables and chairs and engagement on mobility interventions. Briefing sessions continue with Councillors on the Mobility Interventions, to improve cycle and pedestrian facilities. New working arrangements continue, including rotation of shifts/attendance, division of works teams to different locations, remote working and longer flexible office hours have been implemented. Updates on services affected, by department are detailed below: Community, Culture and Arts The Community Centres remain closed due to the Covid 19 restrictions. Samuel Beckett and Mountown Community Centres opened on the 29th June 2020. The remaining centres will open in phases up to the Estate Management Meetings with committees have moved to an online platform. This gives the committee members an opportunity to stay in contact and to continue discussions relating to future plans of work. COVID-19 Community Call Helpline The Community response to Covid-19 is being led and coordinated by Dún Laoghaire- Rathdown County Council in collaboration with a wide-range of stakeholders in the Community Response Forum, supported by a wide range of community and volunteer groups. A Covid-19 Emergency Fund has been introduced by the Department of Rural and Community Development. The Fund is designed to support groups/organisations involved in Community Call Covid-19 Community Response to Covid 19: Helpline and email address set up and promoted across all communication channels Operates 7 days a week from 8 am to 8 pm The Community Call Helpline has dealt with 3500 calls since it commenced on 30 March.