Bank Interest Rate Margin, Portfolio Composition and Institutional Constraints

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Up to EUR 3,500,000.00 7% Fixed Rate Bonds Due 6 April 2026 ISIN

Up to EUR 3,500,000.00 7% Fixed Rate Bonds due 6 April 2026 ISIN IT0005440976 Terms and Conditions Executed by EPizza S.p.A. 4126-6190-7500.7 This Terms and Conditions are dated 6 April 2021. EPizza S.p.A., a company limited by shares incorporated in Italy as a società per azioni, whose registered office is at Piazza Castello n. 19, 20123 Milan, Italy, enrolled with the companies’ register of Milan-Monza-Brianza- Lodi under No. and fiscal code No. 08950850969, VAT No. 08950850969 (the “Issuer”). *** The issue of up to EUR 3,500,000.00 (three million and five hundred thousand /00) 7% (seven per cent.) fixed rate bonds due 6 April 2026 (the “Bonds”) was authorised by the Board of Directors of the Issuer, by exercising the powers conferred to it by the Articles (as defined below), through a resolution passed on 26 March 2021. The Bonds shall be issued and held subject to and with the benefit of the provisions of this Terms and Conditions. All such provisions shall be binding on the Issuer, the Bondholders (and their successors in title) and all Persons claiming through or under them and shall endure for the benefit of the Bondholders (and their successors in title). The Bondholders (and their successors in title) are deemed to have notice of all the provisions of this Terms and Conditions and the Articles. Copies of each of the Articles and this Terms and Conditions are available for inspection during normal business hours at the registered office for the time being of the Issuer being, as at the date of this Terms and Conditions, at Piazza Castello n. -

Margin Requirements Across Equity-Related Instruments: How Level Is the Playing Field?

Fortune pgs 31-50 1/6/04 8:21 PM Page 31 Margin Requirements Across Equity-Related Instruments: How Level Is the Playing Field? hen interest rates rose sharply in 1994, a number of derivatives- related failures occurred, prominent among them the bankrupt- cy of Orange County, California, which had invested heavily in W 1 structured notes called “inverse floaters.” These events led to vigorous public discussion about the links between derivative securities and finan- cial stability, as well as about the potential role of new regulation. In an effort to clarify the issues, the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston sponsored an educational forum in which the risks and risk management of deriva- tive securities were discussed by a range of interested parties: academics; lawmakers and regulators; experts from nonfinancial corporations, investment and commercial banks, and pension funds; and issuers of securities. The Bank published a summary of the presentations in Minehan and Simons (1995). In the keynote address, Harvard Business School Professor Jay Light noted that there are at least 11 ways that investors can participate in the returns on the Standard and Poor’s 500 composite index (see Box 1). Professor Light pointed out that these alternatives exist because they dif- Peter Fortune fer in a variety of important respects: Some carry higher transaction costs; others might have higher margin requirements; still others might differ in tax treatment or in regulatory restraints. The author is Senior Economist and The purpose of the present study is to assess one dimension of those Advisor to the Director of Research at differences—margin requirements. -

Margin Requirements and Equity Option Returns∗

Margin Requirements and Equity Option Returns∗ Steffen Hitzemann† Michael Hofmann‡ Marliese Uhrig-Homburg§ Christian Wagner¶ December 2017 Abstract In equity option markets, traders face margin requirements both for the options them- selves and for hedging-related positions in the underlying stock market. We show that these requirements carry a significant margin premium in the cross-section of equity option returns. The sign of the margin premium depends on demand pressure: If end-users are on the long side of the market, option returns decrease with margins, while they increase otherwise. Our results are statistically and economically significant and robust to different margin specifications and various control variables. We explain our findings by a model of funding-constrained derivatives dealers that require compensation for satisfying end-users’ option demand. Keywords: equity options, margins, funding liquidity, cross-section of option returns JEL Classification: G12, G13 ∗We thank Hameed Allaudeen, Mario Bellia, Jie Cao, Zhi Da, Matt Darst, Maxym Dedov, Bjørn Eraker, Andrea Frazzini, Ruslan Goyenko, Guanglian Hu, Hendrik Hülsbusch, Kris Jacobs, Stefan Kanne, Olaf Korn, Dmitriy Muravyev, Lasse Pedersen, Matthias Pelster, Oleg Rytchkov, Ivan Shaliastovich, as well as participants of the 2017 EFA Annual Meeting, the SFS Cavalcade North America 2017, the 2017 MFA Annual Meeting, the SGF Conference 2017, the Conference on the Econometrics of Financial Markets, the 2016 Annual Meeting of the German Finance Association, the Paris December 2016 Finance Meeting, and seminar participants at the Center for Financial Frictions at Copenhagen Business School, the CUHK Business School, the University of Gothenburg, and the University of Wisconsin-Madison for valuable discussions and helpful comments and suggestions. -

Margin-Based Asset Pricing and Deviations from the Law of One Price∗

Margin-Based Asset Pricing and Deviations from the Law of One Price∗ Nicolae Gˆarleanu and Lasse Heje Pedersen† Current Version: September 2009 Abstract In a model with heterogeneous-risk-aversion agents facing margin constraints, we show how securities’ required returns are characterized both by their betas and their margins. Negative shocks to fundamentals make margin constraints bind, lowering risk-free rates and raising Sharpe ratios of risky securities, especially for high-margin securities. Such a funding liquidity crisis gives rise to “bases,” that is, price gaps between securities with identical cash-flows but different margins. In the time series, bases depend on the shadow cost of capital, which can be captured through the interest- rate spread between collateralized and uncollateralized loans, and, in the cross section, they depend on relative margins. We apply the model empirically to CDS-bond bases and other deviations from the Law of One Price, and to evaluate the Fed lending facilities. ∗We are grateful for helpful comments from Markus Brunnermeier, Xavier Gabaix, Andrei Shleifer, and Wei Xiong, as well as from seminar participants at the Bank of Canada, Columbia GSB, London School of Economics, MIT Sloan, McGill University, Northwestern University Kellog, UT Austin McCombs, UC Berkeley Haas, the Yale Financial Crisis Conference, and Yale SOM. †Gˆarleanu (corresponding author) is at Haas School of Business, University of California, Berkeley, NBER, and CEPR; e-mail: [email protected]. Pedersen is at New York University, NBER, and CEPR, 44 West Fourth Street, NY 10012-1126; e-mail: [email protected], http://www.stern.nyu.edu/∼lpederse/. -

Guide for Margin Finance

Guide for Margin Finance Guide for Margin Finance Contents Margin Finance What is margin finance? How does margin finance take place? Risks of margin finance Acknowledgement 1 / 6 Guide for Margin Finance Margin Finance Investors should request copies from their financial brokers and familiarize themselves with the following: The guide issued by the Jordan Securities Commission, Margin Finance Instructions, the list of securities allowed to be margin financed, and the margin finance agreement. Investors should also sign an acknowledgement that they have familiarized themselves with the above in order to protect their rights. This guide aims to familiarize investors with the concept of margin finance and the risks related to it. It should be read thoroughly. 2 / 6 Guide for Margin Finance What is margin finance? The term “Margin Finance” shall mean the financing by a Financial Broker of a part of the value of the securities in the margin finance account by guaranteeing the securities in that account. How does margin finance take place? Say you are an investor and you buy shares worth JD 5,000 with your own money, then the value of these shares rises to JD 7,500, your profit would be 50%. But if you finance your purchase of these shares through margin finance the shares, you would pay JD 2,500 of your own money and your broker would pay JD 2,500, so your profit would be 100%. In other words, your profit is greater when you margin finance. If, on the other hand, the value of the shares drops to JD 2,500 after you had bought them with your own money, your loss would be 50%; but if you had bought them from the margin finance account, your loss would be 100% plus any interest payments and fees. -

EQUITY EQUITY DER- PARAMETERS METHODOLOGIES USED in MARGIN CALCULATIONS Manual

EQUITY EQUITY DER- PARAMETERS METHODOLOGIES USED IN MARGIN CALCULATIONS Manual APRIL 2021 V02.0 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive summary ...................................................................................... 3 Methodologies for determining Margin Parameters used in Margin Calculations ...................................................................................................... 5 2.1 Main parameters...................................................................................... 6 2.2 Margin Interval calculation ...................................................................... 7 2.2.1 Defining Coverage Level......................................................................... 7 2.2.2 Determining the Margin Interval for Equity cash ........................................ 7 2.2.3 Determining the Margin Interval for Equity derivatives .............................. 10 2.3 Product Group Offset Factor .................................................................. 10 2.4 Futures Straddle Margin ........................................................................ 10 2.4.1 Straddle Interest Rate Methodology ........................................................ 11 2.4.2 Straddle Correlation Methodology ........................................................... 13 2.5 Minimum Initial Margin ......................................................................... 13 2.6 Margin Intervals and Additional Margin changes ................................... 14 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This -

Margin-Based Asset Pricing and Deviations from the Law of One Price

Margin-based Asset Pricing and Deviations from the Law of One Price Nicolae Garleanuˆ University of California Lasse Heje Pedersen New York University In a model with heterogeneous-risk-aversion agents facing margin constraints, we show how securities’ required returns increase in both their betas and their margin require- ments. Negative shocks to fundamentals make margin constraints bind, lowering risk-free rates and raising Sharpe ratios of risky securities, especially for high-margin securities. Such a funding-liquidity crisis gives rise to “bases,” that is, price gaps between securities with identical cash-flows but different margins. In the time series, bases depend onthe shadow cost of capital, which can be captured through the interest-rate spread between collateralized and uncollateralized loans and, in the cross-section, they depend on rela- tive margins. We test the model empirically using the credit default swap–bond bases and other deviations from the Law of One Price, and use it to evaluate central banks’ lending facilities. (JEL G01, G12, G13, E44, E50) The paramount role of funding constraints becomes particularly salient dur- ing liquidity crises, with the one that started in 2007 being an excellent case in point. Banks unable to fund their operations closed down, and the fund- ing problems spread to other investors, such as hedge funds, that relied on bank funding. Therefore, traditional liquidity providers became forced sellers, interest-rate spreads increased dramatically, Treasury rates dropped sharply, and central -

Equity Friendly Or Noteholder Friendly? the Role of Collateral Asset Managers in the Col- Lapse of the Market for ABS-Cdos

Equity friendly or noteholder friendly? The role of collateral asset managers in the col- lapse of the market for ABS-CDOs Thomas Mählmann Chair of Banking and Finance, Catholic University of Eichstaett-Ingolstadt, Auf der Schanz 49, 85049 Ingolstadt, Germany This version: April 2012 Abstract This paper shows that ABS-CDOs (i.e., collateralized debt obligations backed by asset- backed securities) managed by large market share managers have higher ex post collateral default rates. The paper also finds that (1) large manager deals, while having higher realized default rates, do not carry more default risk ex ante (at origination), as measured by the deal fraction rated AAA or the size of the equity tranche, (2) ex post, these deals have higher per- centages of home-equity loans, subprime RMBS and synthetic assets in their collateral pools, and larger asset-specific default rates and issuer concentration levels, (3) compared to smaller managers, large market share manager deals pay out higher cash flows to equity tranche in- vestors prior to the start of the subprime crisis (July 2007) but significantly lower cash flows afterwards, and (4) investors demand a (price) discount on non-equity tranches sold by large manager deals. In sum, this evidence is consistent with a conflict of interest/risk shifting ar- gument: some managers boost their market share by catering to the interests of the deals’ eq- uity sponsors. JEL classification: G21, G28 Keywords: Conflict of interest, Credit Rating, Collateralized Debt Obligation, Yield Spread Tel.: +49 841 937 1883; fax: +49 841 937 2883. E-mail address: [email protected] 1. -

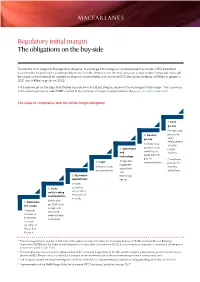

Regulatory Initial Margin the Obligations on the Buy-Side

Regulatory initial margin The obligations on the buy-side To date, the firms subject to the regulatory obligation to exchange initial margin on uncleared over-the-counter (OTC) derivatives have been the heaviest users, predominantly on the sell-side. However, over the next two years a large number of buy-side firms will be caught as the threshold for compliance drops to include entities with uncleared OTC derivatives portfolios of €50bn or greater in 2021 and of €8bn or greater in 2022.1 In this note we set out the steps that affected buy-side firms should be taking to prepare for the exchange of initial margin.2 For a summary of the wider requirements under EMIR3 relevant to the exchange of margin on uncleared derivatives, see our earlier publication.4 The steps to compliance with the initial margin obligation 7. Post go-live Periodic audit 6. Confirm process to go-live verify effectiveness Confirm initial of initial margin set-up 5. Operations margin operating as and solution. expected from technology date of Compliance Scope and 4. Legal implementation. process for implement Negotiate legal ongoing operational documentation. obligations. and 3. Custodian technology appointment set-up. Choose 2. If yes, custodian, notify trading select either counterparties third party or tri-party. 1. Determine Notification if in scope by ISDA initial margin self- Complete disclosure analysis as letter/bilateral to whether notification. in scope for either of Phase 5 or Phase 6. 1 These timings reflect a number of deferrals of the implementation that follow the recommendations of The Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) and the International Organization of Securities Commissions (IOSCO), most recently in response to coronavirus challenges in a statement dated 3 April 2020. -

The Price of Protection: Derivatives, Default Risk, and Margining∗

The Price of Protection: Derivatives, Default Risk, and Margining∗ RAJNA GIBSON AND CARSTEN MURAWSKI† This draft: January 22, 2007 ABSTRACT Like many financial contracts, derivatives are subject to default risk. A very popular mechanism in derivatives markets to mitigate the risk of non-performance on contracts is margining. By attaching collateral to a contract, margining supposedly reduces default risk. The broader impacts of the different types of margins are more ambiguous, however. In this paper we develop both, a theoretical model and a simulated market model to investigate the effects of margining on trading volume, wealth, default risk, and welfare. Capturing some of the main characteristics of derivatives markets, we identify situations where margining may increase default risk while reducing welfare. This is the case, in particular, when collateral is scarce. Our results suggest that margining might have a negative effect on default risk and on welfare at times when market participants expect it to be most valuable, such as during periods of market stress. JEL CLASSIFICATION CODES: G19, G21. KEY WORDS: Derivative securities, default risk, collateral, central counterparty, systemic risk. ∗Supersedes previous versions titled “Default Risk Mitigation in Derivatives Markets and its Effectiveness”. This paper benefited from comments by Charles Calomiris, Enrico Di Giorgi, Hans Geiger, Andrew Green, Philipp Haene, Markus Leippold, David Marshall, John McPartland, Jim Moser, Robert Steigerwald, and Suresh Sundaresan. The paper was presented at the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago in January 2007, the Annual Meeting of the European Finance Association in August 2006, the FINRISK Research Day in June 2006, and the conference “Issues Related to Central Counterparty Clearing” at the European Central Bank in April 2006. -

Lecture 7 – Structured Finance (CDO, CLO, MBS, ABL, ABS)

Investment Banking Prof. Droussiotis Lecture 7 – Structured Finance (CDO, CLO, MBS, ABL, ABS) There are several main types of structured finance instruments. Asset-backed securities (ABS) are bonds or notes based on pools of assets, or collateralized by the cash flows from a specified pool of underlying assets. Mortgage-backed securities (MBS) are asset-backed securities the cash flows of which are backed by the principal and interest payments of a set of mortgage loans. o Residential Mortgage-Backed Securities, (RMBS) deal with Residential homes, usually single family. o Commercial Mortgage-Backed Securities (CMBS) are for Commercial Real Estate such as malls or office complexes. o Collateralized mortgage obligations (CMOs) are securitizations of mortgage-backed securities. Collateralized debt obligations (CDOs) consolidate a group of fixed income assets such as high-yield debt or asset-backed securities into a pool, which is then divided into various tranches. o Collateralized bond obligations (CBOs) are CDOs backed primarily by corporate bonds. o Collateralized loan obligations (CLOs) are CDOs backed primarily by leveraged bank loans. o Commercial real estate collateralized debt obligations (CRE CDOs) are CDOs backed primarily by commercial real estate loans and bonds. Collateral Analysis Collateral is assets provided to secure an obligation. Traditionally, banks might require corporate borrowers to commit company assets as security for loans. Today, this practice is called secured lending or asset-based lending. Collateral can take many forms: property, inventory, equipment, receivables, oil reserves, etc. 45 Investment Banking Prof. Droussiotis Advance Debt Rates (ABL BV of Capacity Facility) Assets based on ($ mm) Collateral Cash 100% 50.00 50.00 A/R 85% 200.00 170.00 Inventory 50% 150.00 75.00 Fixed 50% Assets 300.00 150.00 Investments 50% 100.00 50.00 Total 800.00 495.00 A more recent development is collateralization arrangements used to secure repo, securities lending and derivatives transactions. -

2.3 Bilateral Margin Requirements for Over-The-Counter Derivatives

2.3 Bilateral margin requirements for over-the-counter derivatives The global financial crisis between 2007 and 2008 highlighted the need to improve the regulation of over- the-counter (OTC) derivatives markets, aiming both to limit risk-taking and to increase transparency. As a result, the Group of Twenty (G20), of which Brazil is a member, agreed in 2009 to implement a reform agenda covering the OTC derivatives markets, in order to establish international standards to be followed by its member countries. As part of this agenda, the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) and the International Organization of Securities Commissions (IOSCO) published in 2015 the principles of margin requirements for derivative transactions not settled through a central counterparty (CCP). The publication of Resolution nº. 4,662 of May 25, 2018, by the National Monetary Council (CMN), and Circular nº. 3,902, of May 30, 2018, by the Central Bank of Brazil (BCB) placed Brazil in the group of countries which have implemented the margin requirements according to the G20 agreement. Bilateral margin requirements consist of the exchange of financial instruments between counterparties of an OTC derivative transaction in order to protect each one of them from losses caused by the inability of the other counterparty to honor its financial obligations related to the transaction. Resolution nº. 4,662, of 2018, defines two types of margins: the variation margin, which is intended to protect the parts of the transaction from their respective current exposures and is determined based on the market value of derivatives contracts; and the initial margin, which is intended to protect the parties of the transaction from risks arising from their respective potential future exposures, as a result of changes in the future prices of the underlying assets of these contracts.