High-Tech Trash: Glitch, Noise, and Aesthetic Failure

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ryan Trecartin: Data Purge

Ryan Trecartin: Data Purge by Jon Davies The young American artist Ryan Trecartin’s vertiginous performance, media and installation practice seeks to give physical form to the abstractions that govern life in the digital age. The structures and motifs of globalized, networked media and communications become characters, narratives and environments in his work. Cyberculture is rewired through the fallible human body, with all its entropic, expressive energies and potential for physical and communicative breakdown. The result is a messy and excessive sensory bombardment that scrambles his viewers’ processors and rewires their comprehension of cinematic storytelling, time and space. Consequently, Trecartin’s work has commanded the art world’s attention in a matter of a few short years. Trecartin was born in 1981 in Webster, Texas, and raised in rural Ohio. He attended the Rhode Island School of Design,1 where he studied video and animation, receiving his bfa in 2004. Relatively cheap to live Ryan Trecartin in, packed with art students and close (but not too close) to New York, P.opular S.ky (section ish), the city of Providence is known for being a hotbed of discipline-crossing 2009, Still from an diy experimentation in terms of culture and community. It was here that HD video. Courtesy the artist and Elizabeth Dee Trecartin found his crew of like-minded creators, dubbed the xppl (New York). (Experimental People Band). Upon graduation, Trecartin and friends 20 Screen Space SWITCH 21 Ryan Trecartin I-Be Area, 2007, Still from a video. Courtesy the artist and Elizabeth Dee (New York). Trecartin’s characters are digital data and they know it. -

Resisting the Logic of Late Capitalism in the Digital Age

Performative identity in networked spaces: Resisting the logic of late capitalism in the digital age Kerry Doran General Honors Thesis Professor Claire Farago – Thesis Advisor Art History Professor Fred Anderson – General Honors Council Representative Honors Program, History Professor Robert Nauman – Art History Honors Council Representative Art History Professor Mark Amerika – Committee Member Studio Arts Professor Karen S. Jacobs – Committee Member English University of Colorado Boulder April 4, 2012 CONTENTS Abstract Acknowledgements Preface I. Postmodernism, late capitalism, and schizophrenia Jean Baudrillard Frederic Jameson Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari II. The Multifariously Paradoxical Culture Industry The Situationist International, dérive, and détournement Situationist tactics today III. Facebook, or, the virtual embodiment of consumer capitalism Me, myself, and Facebook Why some people “Like” Facebook Capitalism 101: Objectification, alienation, and the fetishism of commodities Every detail counts. “Facebook helps you connect and share with the people in your life” My real (fake) Facebook A note on following pieces IV. Performative identity in networked spaces “Hey! My name’s Ryan! I’m a video kid. Digital.” Editing, fictionalizing, and performing the self Schizophrenic conceptual personae Conclusion: A postmodernism of resistance, or something else? 2 ABSTRACT The technological developments of the twenty-first century, most significantly the commercialization and widespread use of the Internet and its interactive technologies, -

WHITNEY BIENNIAL 2006: DAY for NIGHT to OPEN Signature Survey Measuring the Mood of Contemporary American Art, March 2-May 28, 2006

Press Release Contact: Jan Rothschild, Stephen Soba, Meghan Bullock (212) 570-3633 or [email protected] www.whitney.org/press February 2006 WHITNEY BIENNIAL 2006: DAY FOR NIGHT TO OPEN Signature survey measuring the mood of contemporary American art, March 2-May 28, 2006 Peter Doig, Day for Night, 2005. Private Collection; courtesy Contemporary Fine Arts, Berlin. The curators have announced their selection of artists for the 2006 Whitney Biennial, which opens to the public on March 2, and remains on view at the Whitney Museum of American Art through May 28, 2006. The list of participating artists appears at the end of this release. Whitney Biennial 2006: Day for Night is curated by Chrissie Iles, the Whitney’s Anne & Joel Ehrenkranz Curator, and Philippe Vergne, the Deputy Director and Chief Curator of the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis. The Biennial’s lead sponsor is Altria. "Altria Group, Inc. is proud to continue its forty year relationship with the Whitney Museum of American Art by sponsoring the 2006 Biennial exhibition," remarked Jennifer P. Goodale, Vice President, Contributions, Altria Corporate Services, Inc. "This signature exhibition of some of the most bold and inspired work coming from artists' studios reflects our company's philosophy of supporting innovation, creativity and diversity in the arts." Whitney Biennial 2006: Day for Night takes its title from the 1973 François Truffaut film, whose original French name, La Nuit américaine, denotes the cinematic technique of shooting night scenes artificially during the day, using a special filter. This is the first Whitney Biennial to have a title attached to it. -

Ryan Trecartin Biography

RYAN TRECARTIN BIOGRAPHY Born in Webster, TX, 1981. Lives and works in Los Angeles, CA. Education: B.F.A., Rhode Island School of Design, Providence, RI, 2004 Selected Solo Exhibitions: 2019 “Re’Search Wait’S,” Sprüth Magers, Berlin, Germany, September 12 – December 21, 2019 “Comma Boat: Ryan Trecartin,” Plug In Institute of Contemporary Art, Winnipeg, Canada, April 27 – June 30, 2019 “Lizzie Fitch | Ryan Trecartin: The Movies,” Fondazione Prada, Milan, Italy, April 6 – September 30, 2019 “Lizzie Fitch/Ryan Trecartin,” Fondazione Prada, Milan, Italy, April 6 – August 5, 2019; catalogue 2018 “Ryan Trecartin: Re’Search Wait’S,” Pond Society, Shanghai, China, November 7, 2018 – January 20, 2019 “Lizzie Fitch/Ryan Trecartin,” Baltimore Museum of Art, Baltimore, MA, October 7, 2018 – January 6, 2019 “Lizzie Fitch/Ryan Trecartin,” Astrup Fearnly Museet, Oslo, Norway, February 22 – May 20, 2018 2016 “Lizzie Fitch/Ryan Trecartin,” Andrea Rosen Gallery, New York, NY, March 19 – April 20, 2016 “Ryan Trecartin: Six Movies,” Art Gallery of Western Australia, Perth, Australia, January 30 – May 8, 2016 2015 “Re’Search Wait'S,” National Gallery of Victoria, Victoria, Australia, May 15 – September 13, 2015 “SITUATION #1: Ryan Trecartin,” Fotomuseum Winterthur, Winterthur, Switzerland, April 10 – June 7, 2015 2014 “Ryan Trecartin: SITE VISIT,” Kunst-Werke Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin, Germany, September 14, 2014 – February 15, 2015 “Lizzie Fitch/Ryan Trecartin: Priority Innfield,” Zabludowicz Collection, London, UK, October 2 – December 21, -

Art Los Angeles Reader ACID INTERIORS | Nº 3 | JANUARY 2017

JANUARY 2017 Art Los Angeles Reader ACID INTERIORS | Nº 3 | JANUARY 2017 Pool The new fragrance by Sean Raspet Available for a limited time at reader.la/pool ART LOS ANGELES READER Art Los Angeles Reader ACID INTERIORS | Nº 3 | JANUARY 2017 Lost Enchantment From the Editor Interior designer Tony Duquette was known for bedazzling style. A short-lived Malibu ranch would have been his crown jewel. Kate Wolf Every single scene in Rainer Werner 1970s black artists’ interventions into public Fassbinder’s newly rediscovered World on a space, to see what rituals and reorientations Wire features two central colors: burnt or- were required for making the city a place ange and emerald blue. Made in 1973, that they could inhabit. And Travis Diehl digs into Infrastructure Sketches era’s cybernetic systems thinking (everything the history of the New York Times’ coverage In the late 1970s, Barbara McCullough and Senga Nengudi exited Ed Ruscha's is related) found an exquisite analogue in the of LA art, diagnosing a host of antipathic, freeway and claimed land under the off-ramps. conspiracy theory of simulation, which mo- boostered biases. Aria Dean tivates the film’s science fiction plot (we’re The theme acid interiors is inspired by stuck in a virtual reality, we just have no idea). William Leavitt’s theatrical obsession with The colors of the interiors seem to prove the mid-century design, his installations of ge- protagonist’s suspicion: in his apartment, his neric sets that deal with the drama of stuff. Pool office, the restaurant, his secretary’s jacket, I am thrilled to present a work Leavitt made A new fragrance made with synthetic compounds. -

Ryan Trecartin

Ryan Trecartin Born in Webster, TX, 1981 Lives and works in Philadelphia, PA EDUCATION 2004 BFA, Rhode Island School of Design SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2008 Wexner Center for the Arts, Columbus, OH Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, CA Galerie Nathalie Obadia, Paris 2007 I-Be Area, Elizabeth Dee Gallery, New York, NY Big Room Now, Crane Arts, Philadelphia, PA 2006 I Smell Pregnant, QED, Los Angeles, CA GROUP EXHIBITIONS 2008 Freeway Balconies, Deutsche Guggenheim, Berlin, Germany, curated by Collier Schorr Lustwarande 08-Wanderland, Tilburg, The Netherlands Television Delivers People, The Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, NY 2007 Present Future 2007, Tornio, Italy La Triennale di Milano, TIMER, Milan, Italy Between Two Deaths, ZKM Karlsruhe, curated by Ellen Blumenstein, Germany 2006 Action Adventure, Canada Gallery, New York USA Today, Works from the Saatchi Collection, Royal Academy of Arts, Burlington Gardens, London, UK (catalogue) Metro Pictures, The Moore Space, Miami, FL Whitney Biennial 2006, Day for Night, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, NY Schindler House, curated by Doug Aitken, Los Angeles, LA 2005 Sympathetic Magic, Planaria, New York, NY SCREENINGS AND COMMISSIONS 2008 I- Be Area, TBA:08, PICA, Portland, OR I- Be Area, New York Underground Film Festival I-Be Area, A Family Finds Entertainment, Tommy-Chat Just Emailed Me, Gallery of Modern Art, Queensland, Australia Valentine’s Day Girl, La Casa Encendida, Madrid, Spain I-Be Area, Madison Museum of Contemporary Art, WI 2007 I-Be Area, New Museum, New York, NY I-Be Area, -

Tina Rivers Ryan

McLuhan’s Bulbs: Light Art and the Dawn of New Media Tina Rivers Ryan Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor in Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2016 © 2016 Tina Rivers Ryan All rights reserved ABSTRACT McLuhan’s Bulbs: Light Art and the Dawn of New Media Tina Rivers Ryan “McLuhan’s Bulbs” argues that the 1960s movement of “light art” is the primary site of negotiation between the discourses of “medium” and “media” in postwar art. In dialogue with the contemporaneous work of Marshall McLuhan, who privileged electric light as the ur- example of media theory, light art eschewed the traditional symbolism of light in Western art, deploying it instead as a cipher for electronic media. By embracing both these new forms of electronic media and also McLuhan’s media theory, light art ultimately becomes a limit term of the Greenbergian notion of medium-specificity, heralding the transformation of “medium” into “media” on both a technological and a theoretical level. This leads to a new understanding of the concept of media as not peripheral, but rather, central to the history and theory of contemporary art. Drawing on extensive archival research to offer the first major history of light art, the project focuses in particular on the work of leading light artist Otto Piene, whose sculptural “light ballets,” “intermedia” environments, and early video projects responded to the increasing technological blurring of media formats by bringing together sound and image, only to insist on the separation between the two. Piene’s position would be superseded by the work of light artists who used electronic transducers to technologically translate between light and other phenomena, particularly sounds. -

June 22, 2014 High Performance. the JULIA

March 16 –June 22, 2014 Press Information High Performance. The JULIA STOSCHEK February 2014 COLLECTION as Guest at the ZKM. Time-based Media Art since 1996 High Performance. The JULIA STOSCHEK COLLECTION as guest at the ZKM. Time-based Media Art Bearing the title High Performance. Time-based Media Art, since 1996 the JULIA STOSCHEK COLLECTION, based in Düsseldorf Exhibition since 1996, presents key works of time-based media art at Location the ZKM | Karlsruhe from March 16 till June 22, 2014. With ZKM | Media Museum large-format video works and films, as well as multichan- nel spatial installations, the exhibition demonstrates that Press Conference Fri, Mar. 14, 2014, 9.30 a.m. as an artistic medium, video art, which first began fifty Opening years ago, has lost nothing of its force. Sat, Mar. 15, 2014, 6 p.m. Inspired by the risky maneuvers of a Chris Burden, in his video work Duration Mar. 16–June 22, 2014 High Performance (2000), artist Aaron Young documents a motorbike rider burning black tracks with the back wheel and by applying the front brakes on the concrete floor of his studio. Clouds of smoke, Press Contact Dominika Szope which emerge through the friction process, gradually cloud the scen- Head of Department Press and ery. In this creative, high-performance, performative act destructive Public Relations Tel: +49 (0)721 / 8100 – 1220 action and creative violence merge in a threatening contradiction, in which man and machine are driven to the extremes of performance Constanze Heidt Assistant Press and Public capability to the point of complete disappearance. -

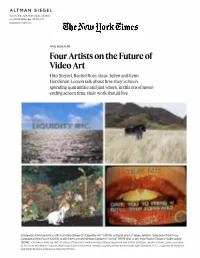

Four Artists on the Future of Video

ALTMAN SIEGEL 1150 25TH ST. SAN FRANCISCO, CA 94107 tel:415.576.9300 / fax:415.373.4471 www.altmansiegel.com TRUE BELIEVERS Four Artistso n the Future of VideoArt Hito Steyerl, Rachel Rose, Isaac Julien and Lynn Hershman Leeson talk about how they've been spending quarantine and just where, in this era of never ending screen time, their work should live. Clockwise from top left: a still from Hito Steyerl's "Liquidity Inc:• (2014); a digital print of Isaac Julien's "Lessons of the Hour (Lessons of the Hour)" (2019); a still from Lynn Hershman Leeson's "Lorna" (1979-84); a still from Rachel Rose's "Lake Valley" (2016). Clockwise from top left: courtesy of the artist, Andrew Kreps Gallery, New York and Esther Schipper, Berlin;© Isaac Julien. courtesy of the artist and Metro Pictures, New York;© Lynn Hershman Leeson, courtesy of the artist and Bridget Donahue, N.Y.C.; courtesyof the artist and Gavin Brown's enterprise New York/Rome By Andrew Russeth July 22, 2020 When coronavirus shuttered just about every gallery in the United States and confined many to their homes, museum curators and dealers had to improvise. Overnight, the only way they could show art was digitally. In some cases, this meant posting photos of paintings or using cameras to offer 360-degree virtual tours of exhibitions — to varying degrees of success. But then there were the works that were designed to be viewed on a screen, which have enjoyed a sort of a renaissance. On many Friday nights since April, the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York has streamed video art by Alex Da Corte, Juan Antonio Olivares and Adelita Husni-Bey, to name a few. -

SYLLABUS ART 260 Intro Video CHANG FALL 2017 2P

ART 260 Introduction To Video and Time-Based USC Roski School Experimentation Units: 4 units of Art and Design Term—Day—Time: Fall 2017 T/TH 2:00-4:50PM Location: Watt 6 Instructor: Patty Chang Office: Watt 6 Office Hours: T/TH 11am to noon by appt. Contact Info: [email protected] IT Help: Nikhil Murthy Contact Info: [email protected] Course Description This introductory course involves training and workshops in high-definition digital video cameras, lighting and sound techniques, Adobe Premiere editing software and various computer conversion and collage techniques. Students learn how to create and present video installations with video projectors, monitors, screens, speakers and live streaming. The class will unpack how history, access, culture and technological shifts have influenced and affected how artists and filmmakers work with video and film. From the first Sony Portapak video cameras and live video image to cable television, surveillance, video projectors, computer generated work, 3-d, YouTube, streaming and phone videos. Screenings and lectures will focus on discursive artist practices and the role that film, video, sound, writing, performance, language, abstraction, installation, structure, streaming and narrative forms have played in their work. The class has three sections and three video projects. The first section introduces students to the medium of video art. The second section will focus on videos and films addressing the language of memory, time and duration. The third section of the class will concentrate on works in video installation. The students will come to understand digital video as a flexible tool that is able to communicate ideas through a large variety of conceptual, technical and aesthetic strategies. -

Lizzie Fitch Biography

LIZZIE FITCH BIOGRAPHY Born in Bloomington, IN, 1981. Lives and works in Athens, OH. Education : B.F.A., Rhode Island School of Design, Providence, RI, 2004 Selected Solo Exhibitions: 2019 “Lizzie Fitch / Ryan Trecartin: The Movies,” Fondazione Prada, Milan, Italy, April 6 – September 30, 2019 “Lizzie Fitch/Ryan Trecartin,” Fondazione Prada, Milan, Italy, April 6 – August 5, 2019; catalogue 2018 “Lizzie Fitch/Ryan Trecartin,” Baltimore Museum of Art, Baltimore, MA, October 7, 2018 – January 6, 2019 “Lizzie Fitch/Ryan Trecartin,” Astrup Fearnley Museet, Oslo, Norway, February 23 – May 20, 2018 2016 “Lizzie Fitch/Ryan Trecartin,” Andrea Rosen Gallery, New York, NY, March 19 – April 20, 2016 2014 “Lizzie Fitch/Ryan Trecartin,” Regen Projects, Los Angeles, CA, October 22 – November 26, 2014 “Lizzie Fitch/Ryan Trecartin: Priority Innfield,” Zabludowicz Collection, London, UK, October 2 – December 21, 2014; travels to La Casa Encendida, Madrid, Spain, February 5 – April 24, 2016; Musée d'art contemporain, Montréal, Canada, June 22 – September 5, 2016; catalogue 2012 “Concrete U,” New Galerie, Paris , France, September 8 – October 13, 2012 2009 “Jonathan Delachaux & Lizzie Fitch,” Foxy Productions, New York, NY, January 16 – March 28, 2009 “The Aboutthing (in the air),” Elizabeth Dee Gallery, New York, NY, April 11 – May 16, 2009 2008 “Big Skin,” Time Based Arts Festival, Portland Institute of Contemporary Art, Portland, OR , September 4 – 14, 2008 2007 “Big Room Now: Ryan Trecartin and Lizzie Fitch,” Crane Arts Center, Philadelphia , PA, February -

14 Boston-Area Arts Organizations Partner Around Art + Tech Top Video News Related Exhibitions

Menu icaboston.org TEMPORARY CLOSURE The ICA has voluntarily closed its building to the public to support the city and state in their efforts to contain the spread of Covid-19 and to ensure the health and safety of our staff, visitors, and community. Continue to connect to art and artists remotely with virtual programs, at-home art activities for kids and families, and by shopping online at the ICA Store. 14 Boston-Area Arts Organizations Partner Around Art + Tech Top Video News Related exhibitions 14 Boston-area arts organizations partner on ambitious, region-wide cultural collaboration dedicated to art and innovation, highlighting Boston as a center of technology This winter, cultural organizations throughout Greater Boston are partnering to present an ambitious, region-wide exploration of art and technology, announced Jill Medvedow, Ellen Matilda Poss Director of the Institute of Contemporary Art/Boston (ICA). Aligned with the ICA’s sweeping exhibition Art in the Age of the Internet, 1989 to Today opening February 7, this extraordinary collaboration will oer the public concurrent exhibitions, performances, screenings, and programs at area cultural organizations, all exploring the relationship between art and technology. The organizations partnering with the ICA are: Berklee College of Music Boston Cyberarts Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts at Harvard University deCordova Sculpture Park and Museum Harvard Art Museums Harvard Film Archive Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum MIT List Visual Arts Center Museum of Fine Arts, Boston Museum of Science, Boston Peabody Essex Museum Rose Art Museum at Brandeis University Tus University Art Galleries “Art in the Age of Internet, 1989 to Today gives us the opportunity to examine all the forms of connectivity made possible by the internet, as well as to work in partnership with colleagues and institutions in Greater Boston,” said Medvedow.