Upland Game Birds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sage-Grouse Hunting Season

CHAPTER 11 UPLAND GAME BIRD AND SMALL GAME HUNTING SEASONS Section 1. Authority. This regulation is promulgated by authority of Wyoming Statutes § 23-1-302 and § 23-2-105 (d). Section 2. Hunting Regulations. (a) Bag and Possession Limit. Only one (1) daily bag limit of each species of upland game birds and small game may be taken per day regardless of the number of hunt areas hunted in a single day. When hunting more than one (1) hunt area, a person’s daily and possession limits shall be equal to, but shall not exceed, the largest daily and possession limit prescribed for any one (1) of the specified hunt areas in which the hunting and possession occurs. (b) Evidence of sex and species shall remain naturally attached to the carcass of any upland game bird in the field and during transportation. For pheasant, this shall include the feathered head, feathered wing or foot. For all other upland game bird species, this shall include one fully feathered wing. (c) No person shall possess or use shot other than nontoxic shot for hunting game birds and small game with a shotgun on the Commission’s Table Mountain and Springer wildlife habitat management areas and on all national wildlife refuges open for hunting. (d) Required Clothing. Any person hunting pheasants within the boundaries of any Wyoming Game and Fish Commission Wildlife Habitat Management Area, or on Bureau of Reclamation Withdrawal lands bordering and including Glendo State Park, shall wear in a visible manner at least one (1) outer garment of fluorescent orange or fluorescent pink color which shall include a hat, shirt, jacket, coat, vest or sweater. -

State-Owned Wildlife Management. Areas in New England

United States Department of State-Owned Agriculture I Forest Service Wildlife Management. Northeastern Forest Experiment Station Areas in New England Research Paper NE-623 Ronald J. Glass Abstract 1 State-owned wildlife management areas play an important role in enhancing 1 wildlife populations and providing opportunities for wildlife-related recreational activities. In the six New England States there are 271 wildlife management areas with a total area exceeding 268,000 acres. A variety of wildlife species benefit from habitat improvement activities on these areas. The Author RONALD J. GLASS is a research economist with the Northeastern Forest Experiment Station, Burlington, Vermont. He also has worked with the Economic Research Service of the US. Department of Agriculture and the Alaska Department of Fish and Game. He received MS. and Ph.D. degrees in economics from the University of Minnesota and the State University of New York at Syracuse. Manuscript received for publication 13 February 1989 1 I Northeastern Forest Experiment Station 370 Reed Road, Broomall, PA 19008 I I July 1989 Introduction Further, human population growth and increased use of rural areas for residential, recreational, and commercial With massive changes in land use and ownership, the role development have resulted in additional losses of wildlife of public lands in providing wildlife habitat and related habitat and made much of the remaining habitat human-use opportunities is becoming more important. One unavailable to a large segment of the general public. Other form of public land ownership that has received only limited private lands that had been open to public use are being recognition is the state-owned wildlife management area posted against trespass, severely restricting public use. -

Population Density and Trends in Central Greece VA Bontzorlos, CG

Animal Biodiversity and Conservation 35.2 (2012) 371 Rock partridge (Alectoris graeca graeca) population density and trends in central Greece V. A. Bontzorlos, C. G. Vlachos, D. E. Bakaloudis, E. N. Chatzinikos, E. A. Dedousopoulou, D. K. Kiousis & C. Thomaides Bontzorlos, V. A., Vlachos, C. G., Bakaloudis, D. E., Chatzinikos, E. N., Dedousopoulou, E. A., Kiousis, D. K. & Thomaides, C., 2012. Rock partridge (Alectoris graeca graeca) population density and trends in central Greece. Animal Biodiversity and Conservation, 35.2: 371–380, Doi: https://doi.org/10.32800/abc.2012.35.0371 Abstract Rock partridge (Alectoris graeca graeca) population density and trends in central Greece.— The rock par- tridge is an emblematic species of the Greek avifauna and one of the most important game species in the country. The present study, which combined long term in–situ counts with distance sampling methodology in central Greece, indicated that the species’ population in Greece is the highest within its European distribution, in contrast to all prior considerations. Inter–annual trends suggested a stable rock partridge population both within hunting areas and wildlife refuges, whereas during summer, the species presented significantly higher densities in altitudes of more than 1,000 m, most probably due to the effect of predation at lower zones. The similarity of population structure between wildlife refuges and hunting zones along with the stable population trends demonstrate that rock partridge harvest in the country is sustainable. Key words: Rock partridge, Alectoris graeca graeca, Greece, Population trends, ANOVA models, Constrained ordination, Sustainable harvest. Resumen Densidad de población y tendencias de la perdiz griega oriental (Alectoris graeca graeca) en Grecia central.— La perdiz griega es una especie emblemática de la avifauna griega y una de las especies cinegéticas más importantes del país. -

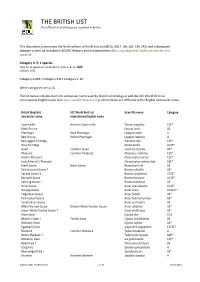

THE BRITISH LIST the Official List of Bird Species Recorded in Britain

THE BRITISH LIST The official list of bird species recorded in Britain This document summarises the Ninth edition of the British List (BOU, 2017. Ibis 160: 190-240) and subsequent changes to the List included in BOURC Reports and announcements (bou.org.uk/british-list/bourc-reports-and- papers/). Category A, B, C species Total no. of species on the British List (Cats A, B, C) = 623 at 8 June 2021 Category A 605 • Category B 8 • Category C 10 Other categories see p.13. The list below includes both the vernacular name used by British ornithologists and the IOC World Bird List international English name (see www.worldbirdnames.org) where these are different to the English vernacular name. British (English) IOC World Bird List Scientific name Category vernacular name international English name Capercaillie Western Capercaillie Tetrao urogallus C3E* Black Grouse Lyrurus tetrix AE Ptarmigan Rock Ptarmigan Lagopus muta A Red Grouse Willow Ptarmigan Lagopus lagopus A Red-legged Partridge Alectoris rufa C1E* Grey Partridge Perdix perdix AC2E* Quail Common Quail Coturnix coturnix AE* Pheasant Common Pheasant Phasianus colchicus C1E* Golden Pheasant Chrysolophus pictus C1E* Lady Amherst’s Pheasant Chrysolophus amherstiae C6E* Brent Goose Brant Goose Branta bernicla AE Red-breasted Goose † Branta ruficollis AE* Canada Goose ‡ Branta canadensis AC2E* Barnacle Goose Branta leucopsis AC2E* Cackling Goose † Branta hutchinsii AE Snow Goose Anser caerulescens AC2E* Greylag Goose Anser anser AC2C4E* Taiga Bean Goose Anser fabalis AE* Pink-footed Goose Anser -

Ruffed Grouse Habitat Use in Western North Carolina

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 5-2002 Ruffed Grouse Habitat Use in Western North Carolina Carrie L. Schumacher University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the Life Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Schumacher, Carrie L., "Ruffed Grouse Habitat Use in Western North Carolina. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2002. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/2192 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Carrie L. Schumacher entitled "Ruffed Grouse Habitat Use in Western North Carolina." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science, with a major in Wildlife and Fisheries Science. Craig A. Harper, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: David A. Buehler, Arnold Saxton Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Carrie L. Schumacher entitled “Ruffed Grouse Habitat Use in Western North Carolina.” I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science, with a major in Wildlife and Fisheries Science. -

The Sleeping Habit of the Willow Ptarmigan

638 GeneralNotes [Oct.[Auk day the bird was found dead by Mr. Wilkin at the edge of the marsh. It had been shot and left by someoneunknown. The bird was turned over to New York Con- servation Department officers and has now been placed in the New York State Museum collection. The bird was a female in excellentbreeding-plumage condition and contained eggs. It weighed 11s/{ pounds, had a wing-spreadof 97 inches,and a length of 54 inches. It was examined in the flesh by both authors of this note.-- GORDO• M. M•AD•, M.D., Strong Memorial Hospital, Rochester,New York, A•D C•,a¾•ro• B. S•ao•ms, Supt. of ConservationEducation, Albany, New York. The sleeping habit of the Willow Ptarmigan.--A frequent statement regard- ing the Willow Ptarmigan (Lagopuslagopus) is that in winter when it goesto roost it drops from flight into the snow, completely burying itself and leaving no tracks that might lead predators to it. E. W. Nelson made this observation years ago in Alaska, and it is given also by Sandys and Van Dyke in their book, 'Upland Game Birds.' Bent (U.S. Nat. Mus. Bull., 162: 194, 1932) in writing on Allen's Ptarmigan of Newfoundland, quotes •I. R. Whitaker as stating that they roost in a shallow scratchingin the snow and are frequently buried by drifts and imprisonedto their death. On Southampton Island, Sutton records the Willow Ptarmigan as roosting and feeding in the same area without attempt at concealment. One night seven slept for the night in sevenconsecutive footprints of his track acrossthe snow. -

Bird List with Jake Mohlmann

Cumulative Bird List with Jake Mohlmann Column A: number of tours (out of 10) on which this species has been recorded Column B: number of days this species was seen on the 2020 tour Column C: maximum daily count for this species on the 2020 tour Column D: H = Heard only A B C D 1 Pacific Loon Gavia pacifica 1 Common Loon Gavia immer 1 Greater White-fronted Goose Anser albifrons 9 Snow Goose 1 65 Chen caerulescens 5 Ross's Goose 1 2 Chen rossii 3 Canada Goose Branta canadensis 1 Wood Duck Aix sponsa 10 Gadwall 3 15 Anas strepera 2 Eurasian Wigeon Anas penelope 10 American Wigeon 2 400 Anas americana 10 Mallard 2 6 Anas platyrhynchos 10 Mexican Duck 1 3 Anas diazi 4 Blue-winged Teal Anas discors 10 Cinnamon Teal 2 10 Anas cyanoptera 10 Northern Shoveler 2 100 Anas clypeata 10 Northern Pintail 1 150 Anas acuta 10 Green-winged Teal 2 50 Anas crecca 9 Canvasback 1 5 Aythya valisineria 6 Redhead 2 2 Aythya americana 10 Ring-necked Duck 2 15 Aythya collaris 1 Greater Scaup 1 2 Aythya marila 9 Lesser Scaup 1 6 Aythya affinis 7 Bufflehead 1 3 Bucephala albeola 10 Common Merganser 1 37 Mergus merganser 10 Ruddy Duck 3 30 Oxyura jamaicensis 5 Scaled Quail Callipepla squamata 10 Gambel's Quail 3 12 Callipepla gambelii 4 Montezuma Quail 1 15 Cyrtonyx montezumae 9 Wild Turkey 2 18 Melagris gallopavo merriamii ________________________________________________________________________________________________________ WINGS ● 1643 N. Alvernon Way Ste. 109 ● Tucson ● AZ ● 85712 ● www.wingsbirds.com (866) 547 9868 Toll free US + Canada ● Tel (520) 320-9868 -

The Birds (Aves) of Oromia, Ethiopia – an Annotated Checklist

European Journal of Taxonomy 306: 1–69 ISSN 2118-9773 https://doi.org/10.5852/ejt.2017.306 www.europeanjournaloftaxonomy.eu 2017 · Gedeon K. et al. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License. Monograph urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:A32EAE51-9051-458A-81DD-8EA921901CDC The birds (Aves) of Oromia, Ethiopia – an annotated checklist Kai GEDEON 1,*, Chemere ZEWDIE 2 & Till TÖPFER 3 1 Saxon Ornithologists’ Society, P.O. Box 1129, 09331 Hohenstein-Ernstthal, Germany. 2 Oromia Forest and Wildlife Enterprise, P.O. Box 1075, Debre Zeit, Ethiopia. 3 Zoological Research Museum Alexander Koenig, Centre for Taxonomy and Evolutionary Research, Adenauerallee 160, 53113 Bonn, Germany. * Corresponding author: [email protected] 2 Email: [email protected] 3 Email: [email protected] 1 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:F46B3F50-41E2-4629-9951-778F69A5BBA2 2 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:F59FEDB3-627A-4D52-A6CB-4F26846C0FC5 3 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:A87BE9B4-8FC6-4E11-8DB4-BDBB3CFBBEAA Abstract. Oromia is the largest National Regional State of Ethiopia. Here we present the first comprehensive checklist of its birds. A total of 804 bird species has been recorded, 601 of them confirmed (443) or assumed (158) to be breeding birds. At least 561 are all-year residents (and 31 more potentially so), at least 73 are Afrotropical migrants and visitors (and 44 more potentially so), and 184 are Palaearctic migrants and visitors (and eight more potentially so). Three species are endemic to Oromia, 18 to Ethiopia and 43 to the Horn of Africa. 170 Oromia bird species are biome restricted: 57 to the Afrotropical Highlands biome, 95 to the Somali-Masai biome, and 18 to the Sudan-Guinea Savanna biome. -

Spatial Ecology of Montezuma Quail in the Davis Mountains of Texas

ECOLOGY OF MONTEZUMA QUAIL IN THE DAVIS MOUNTAINS OF TEXAS A Thesis By CURTIS D. GREENE Submitted to the School of Agricultural and Natural Resource Sciences Sul Ross State University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE December 2011 Major Subject: Range and Wildlife Management ECOLOGY OF MONTEZUMA QUAIL IN THE DAVIS MOUNTAINS OF TEXAS A Thesis By CURTIS D. GREENE Approved as to style and content by: _______________________________ ____________________________ Louis A. Harveson, Ph.D. Dale Rollins, Ph.D. (Chair of Committee) (Member) ____________________________ Patricia Moody Harveson, Ph.D. (Member) _______________________ Robert J. Kinucan, Ph.D. Dean of Agricultural and Natural Resource Sciences ABSTRACT Montezuma quail (Cyrtonyx montezumae) occur throughout the desert mountain ranges in the Trans Pecos of Texas as well as the states of New Mexico and Arizona. Limited information on life history and ecology of the species is available due to the cryptic nature of the bird. Home range, movements, and preferred habitats have been speculated upon in previous literature with the use of observational or anecdotal data. With modern trapping techniques and technologically advanced radio transmitters, Montezuma quail have been successfully monitored providing assessments of their ecology with the use of hard data. The objective of this study was to monitor Montezuma quail to determine home range size, movements, habitat preference, and assess population dynamics for the Davis Mountains population. Over the course of two years (2009 – 2010) a total of 72 birds (36M, 35F, 1 Undetermined) were captured. Thirteen individuals with >25 locations per bird were evaluated in the home range, movement, and habitat selection analyses. -

Conservation Genetics and Management of the Chukar Partridge Alectoris Chukar in Cyprus and the Middle East PANICOS PANAYIDES, MONICA GUERRINI & FILIPPO BARBANERA

Conservation genetics and management of the Chukar Partridge Alectoris chukar in Cyprus and the Middle East PANICOS PANAYIDES, MONICA GUERRINI & FILIPPO BARBANERA The Chukar Partridge Alectoris chukar (Phasianidae) is a popular game bird whose range extends from the Balkans to eastern Asia. The Chukar is threatened by human-mediated hybridization either with congeneric species (Red-Legged A. rufa and Rock A. graeca Partridges) from Europe or exotic conspecifics (from eastern Asia), mainly through introductions. We investigated Chukar populations of the Middle East (Cyprus, Turkey, Lebanon, Israel, Armenia, Georgia, Iran and Turkmenistan: n = 89 specimens) in order to obtain useful genetic information for the management of this species. We sequenced the entire mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) Control Region using Mediterranean (Greece: n = 27) and eastern Asian (China: n = 18) populations as intraspecific outgroups. The Cypriot Chukars (wild and farmed birds) showed high diversity and only native genotypes; signatures of both demographic and spatial expansion were found. Our dataset suggests that Cyprus holds the most ancient A. chukar haplotype of the Middle East. We found A. rufa mtDNA lineage in Lebanese Chukars as well as A. chukar haplotypes of Chinese origin in Greek and Turkish Chukars. Given the very real risk of genetic pollution, we conclude that present management of game species such as the Chukar cannot avoid anymore the use of molecular tools. We recommend that Chukars must not be translocated from elsewhere to Cyprus. INTRODUCTION The distribution range of the most widespread species of Alectoris partridge, the Chukar (A. chukar, Phasianidae, Plate 1), is claimed to extend from the Balkans to eastern Asia. -

Tinamiformes – Falconiformes

LIST OF THE 2,008 BIRD SPECIES (WITH SCIENTIFIC AND ENGLISH NAMES) KNOWN FROM THE A.O.U. CHECK-LIST AREA. Notes: "(A)" = accidental/casualin A.O.U. area; "(H)" -- recordedin A.O.U. area only from Hawaii; "(I)" = introducedinto A.O.U. area; "(N)" = has not bred in A.O.U. area but occursregularly as nonbreedingvisitor; "?" precedingname = extinct. TINAMIFORMES TINAMIDAE Tinamus major Great Tinamou. Nothocercusbonapartei Highland Tinamou. Crypturellus soui Little Tinamou. Crypturelluscinnamomeus Thicket Tinamou. Crypturellusboucardi Slaty-breastedTinamou. Crypturellus kerriae Choco Tinamou. GAVIIFORMES GAVIIDAE Gavia stellata Red-throated Loon. Gavia arctica Arctic Loon. Gavia pacifica Pacific Loon. Gavia immer Common Loon. Gavia adamsii Yellow-billed Loon. PODICIPEDIFORMES PODICIPEDIDAE Tachybaptusdominicus Least Grebe. Podilymbuspodiceps Pied-billed Grebe. ?Podilymbusgigas Atitlan Grebe. Podicepsauritus Horned Grebe. Podicepsgrisegena Red-neckedGrebe. Podicepsnigricollis Eared Grebe. Aechmophorusoccidentalis Western Grebe. Aechmophorusclarkii Clark's Grebe. PROCELLARIIFORMES DIOMEDEIDAE Thalassarchechlororhynchos Yellow-nosed Albatross. (A) Thalassarchecauta Shy Albatross.(A) Thalassarchemelanophris Black-browed Albatross. (A) Phoebetriapalpebrata Light-mantled Albatross. (A) Diomedea exulans WanderingAlbatross. (A) Phoebastriaimmutabilis Laysan Albatross. Phoebastrianigripes Black-lootedAlbatross. Phoebastriaalbatrus Short-tailedAlbatross. (N) PROCELLARIIDAE Fulmarus glacialis Northern Fulmar. Pterodroma neglecta KermadecPetrel. (A) Pterodroma -

Hunting Regulations

WYOMING GAME AND FISH COMMISSION Upland Game Bird, Small Game, Migratory 2021 Game Bird and Wild Turkey Hunting Regulations Conservation Stamp Price Increase Effective July 1, 2021, the price for a 12-month conservation stamp is $21.50. A conservation stamp purchased on or before June 30, 2021 will be valid for 12 months from the date of purchase as indicated on the stamp. (See page 5) wgfd.wyo.gov Wyoming Hunting Regulations | 1 CONTENTS GENERAL 2021 License/Permit/Stamp Fees Access Yes Program ................................................................... 4 Carcass Coupons Dating and Display.................................... 4, 29 Pheasant Special Management Permit ............................................$15.50 Terms and Definitions .................................................................5 Resident Daily Game Bird/Small Game ............................................. $9.00 Department Contact Information ................................................ 3 Nonresident Daily Game Bird/Small Game .......................................$22.00 Important Hunting Information ................................................... 4 Resident 12 Month Game Bird/Small Game ...................................... $27.00 License/Permit/Stamp Fees ........................................................ 2 Nonresident 12 Month Game Bird/Small Game ..................................$74.00 Stop Poaching Program .............................................................. 2 Nonresident 12 Month Youth Game Bird/Small Game Wild Turkey