How Students Use Multimodal Composition to Write About Communities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Top 40 Singles Top 40 Albums

23 February 1992 CHART #798 Top 40 Singles Top 40 Albums Smells Like Teen Spirit Don't Talk Just Kiss The Commitments OST The Globe 1 Nirvana 21 Right Said Fred 1 Various 21 Big Audio Dynamite Last week 2 / 6 weeks BMG Last week - / 1 weeks FESTIVAL Last week 1 / 6 weeks Platinum / BMG Last week - / 1 weeks SONY Rush Cream Nevermind We Can't Dance 2 Big Audio Dynamite 22 Prince 2 Nirvana 22 Genesis Last week 1 / 9 weeks SONY Last week 12 / 14 weeks WARNER Last week 2 / 11 weeks Gold / UNIVERSAL Last week 22 / 11 weeks Gold / VIRGIN Remember The Time Turn It Up Waking Up The Neighbours Blood Sugar Sex Majik 3 Michael Jackson 23 Oaktowns 3.5.7 3 Bryan Adams 23 Red Hot Chili Peppers Last week - / 1 weeks SONY Last week 18 / 9 weeks EMI Last week 4 / 18 weeks Platinum / POLYGRAM Last week 19 / 16 weeks WARNER Justified And Ancient Pride (In The Name) From Time To Time Mr Lucky 4 The KLF 24 Coles & Clivilles 4 Paul Young 24 John Lee Hooker Last week 11 / 4 weeks FESTIVAL Last week - / 1 weeks SONY Last week 3 / 6 weeks Gold / SONY Last week 24 / 19 weeks Gold / VIRGIN Let's Talk About Sex Is It Good To You Shepherd Moons Full House 5 Salt N Pepa 25 Heavy D & The Boyz 5 Enya 25 John Farnham Last week 5 / 17 weeks POLYGRAM Last week 48 / 6 weeks BMG Last week 5 / 11 weeks WARNER Last week 16 / 7 weeks Gold / BMG Remedy Martika's Kitchen Achtung Baby Armchair Melodies 6 The Black Crowes 26 Martika 6 U2 26 David Gray Last week - / 1 weeks WARNER Last week 24 / 7 weeks SONY Last week 8 / 10 weeks Platinum / POLYGRAM Last week 31 / 3 weeks BMG Don't -

The Wanderer Episode 5: Transient Written by Jasmine Louis ACT ONE

The Wanderer Episode 5: Transient Written by Jasmine Louis ACT ONE EXT. SPIRIT REALM - NIGHT A pitch black forest that is overrun by uncommonly wild foliage. The sky is void of any light, but on land, little balls of light bounce from plant to plant. There is a large clearing with a glorious waterfall at the center. The water glows an electric blue color. IZZY, 16, dressed like a 90s teenager, roams around the forest trying to find her way back to the waterfall. She hears the SIREN's STOMPS, RUNS to the nearest bush and hides. Izzy watches as the Siren walks by sniffing the air. Izzy stealthily gets up and makes her way to the waterfall. She reaches into the water and attempts to contact JORDAN. IZZY (whisper) Jordan, have you figured out anything yet...Derek, what about Derek... Joorrdaaan... Jordan! Go the fuck to- There's a loud STOMP and Izzy RUSHES back into the forest. Izzy carefully observes the Siren as it walks to the water and JUMPS in. The Siren swims into the waterfall and disappears. Izzy stares at the waterfall as the song of the Siren begins. Faint images of spirits begin to manifest throughout the clearing. They slowly wander around the clearing and into the forest. IZZY (CONT’D) Holy shit.... Izzy slowly gets up and quietly walks towards the waterfall. INT. IN BETWEEN PLACE - NIGHT An abyss of dark water with a slight tint of blue. Jordan, 16, dressed in old shorts and a t-shirt, floats in the In Between Place. -

April---Shanice-Is-Native-American

Real Teens DIFFERENT Meet teens whose unique experiences might make them seem as if they’re from another world—when in Shanice is a reality they’re just like you. Native —Shanice Britton American Today, roughly 30 percent of I’m a Native American, and I’m from a reservation in Covelo, the 5.2 million Native Americans California, where seven tribes in the U.S. live on reservations. live—including the two that I’m part of, Wailaki and Yuki. A What’s it like to grow up on one? reservation is a place that’s reserved Shanice, 18, shares her story. for Native American tribes by the federal government. About 56 By SHANICE BRITTON, as told to JANE BIANCHI million acres in the country are held for Native American tribes. Some reservations (like the 16 million- The summer before my senior acre Navajo Nation in Arizona, New year of high school, during a four-week Mexico, and Utah) are huge, while science program at the University of others are just over one acre in size. California, Davis, I was eating in a Mine is on the smaller side. People often have cafeteria with some other high school misconceptions about what living students, and this one girl asks me: “Do on a reservation means. Some you live in a teepee?” It was such a silly think, for instance, that I wear a question that, at first, I thought she headdress and moccasins every day. In reality, though, my life was joking! I said, “Are you serious?” probably looks a lot like yours. -

Check out 8 Songs Musical Artists Have

Search TRAILBLAZERS IN MUSIC: CHECK OUT SONGS MUSICAL ARTISTS HAVE SAMPLED FROM WOMEN OF MOTOWN By Brianna Rhodes Photo: Classic Motown - Advertisement - The Sound Of Young America wouldn’t be known for what it is today without the trailblazing Women of Motown. Throughout its 60-year existence, Motown Records made an impact on the world thanks to music genius and founder, Berry Gordy. It's important to note though, that the African- American owned label wouldn’t have reached so many monumental milestones without The Supremes, Martha Reeves & The Vandellas, Mary Wells, The Marvelettes, Tammi Terrell and Gladys Knight. The success of these talented women proved that women voices needed to be heard through radio airwaves everywhere. As a kid, you were probably singing melodies created by these women around the house with family members or even performing the songs in your school’s talent show, not even realizing how much of an impact these women made on Black culture and Black music. This is why it’s important to acknowledge these women during the celebration of the label’s 60th anniversary. The legendary reign of the Women of Motown began back in 1960, with then 17-year-old musical artist Mary Wells with her debut single, “Bye Bye Baby.” Wells, who wrote the song herself, helped Motown attain its first Top 10 R&B hit ever. Wells continued to make history with her chart-topping single, “My Guy” becoming Motown’s fourth No. 1 hit on the Billboard Hot 100 and the company’s first major U.K. single. -

Pittsburgh Legal Journal Thursday, August 11, 2016

4 • Pittsburgh Legal Journal Thursday, August 11, 2016 Handelsman, 2143 Ardmore Blvd., Pittsburgh, Fabian, Jerome, deceased, of Brentwood, Notice PA 15221. PA. No. 01819 of 2016. Fran Fabian, Admrx., TO: Unknown Heirs, Successors, Assigns and FAMILY DIVISION LEGAL ADS 16-04838 Aug 4, 11, 18, 2016 403 East Francis Avenue, Brentwood, PA all Persons, Firms or Associations Claiming 15227 or to Mark F. Bennett, Esq., Berger and Right, Title or Interest from or under Keith N. (Continued from Page 1, Column 2) Hirsch, Laurel B., deceased, of Shaler Green, 800 Waterfront Dr., Pittsburgh, PA Smith, Deceased. Legal notices that are published Township, PA. No. 4106 of 2016. Richard A. 15222. You are hereby notified that on March 27, Bischoff Nanacy L. vs Bischoff Bryan L.; in the Pittsburgh Legal Journal Hirsch, Jr., Extr., 2339 Danbury Lane, Ft. 16-04684 Jul 28; Aug 4, 11, 2016 2016, Plaintiff, Costello Properties, LLC, filed FD-16-008498; Divorce; Complaint in are done so pursuant to Title 45 Mitchell, KY 41017 or to Howard S. Auld, Jr., a Mortgage Foreclosure Complaint endorsed Esq., Howard S. Auld & Associates, 5018 Hackimer, Jr., Anthony William, deceased, Divorce (1 count); Atty(s): Levine Max A Pa. Code 101 et seq. and various with a Notice to Defend, against you in the local court rules. The Pittsburgh William Flynn Hwy., Gibsonia, PA 15044. of Pittsburgh, PA. No. 06883 of 2014. Amelia Court of Common Pleas of Allegheny County, Bines Jennifer, Bines Jennifer vs Legal Journal does not edit any 16-04839 Aug 4, 11, 18, 2016 L. Hackimer, Extrx., 616 Laramido Street, Pennsylvania, docketed at No. -

Songs by Title

Karaoke Song Book Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Nelly 18 And Life Skid Row #1 Crush Garbage 18 'til I Die Adams, Bryan #Dream Lennon, John 18 Yellow Roses Darin, Bobby (doo Wop) That Thing Parody 19 2000 Gorillaz (I Hate) Everything About You Three Days Grace 19 2000 Gorrilaz (I Would Do) Anything For Love Meatloaf 19 Somethin' Mark Wills (If You're Not In It For Love) I'm Outta Here Twain, Shania 19 Somethin' Wills, Mark (I'm Not Your) Steppin' Stone Monkees, The 19 SOMETHING WILLS,MARK (Now & Then) There's A Fool Such As I Presley, Elvis 192000 Gorillaz (Our Love) Don't Throw It All Away Andy Gibb 1969 Stegall, Keith (Sitting On The) Dock Of The Bay Redding, Otis 1979 Smashing Pumpkins (Theme From) The Monkees Monkees, The 1982 Randy Travis (you Drive Me) Crazy Britney Spears 1982 Travis, Randy (Your Love Has Lifted Me) Higher And Higher Coolidge, Rita 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP '03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie And Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1999 Prince 1 2 3 Estefan, Gloria 1999 Prince & Revolution 1 Thing Amerie 1999 Wilkinsons, The 1, 2, 3, 4, Sumpin' New Coolio 19Th Nervous Breakdown Rolling Stones, The 1,2 STEP CIARA & M. ELLIOTT 2 Become 1 Jewel 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind 2 Become 1 Spice Girls 10 Min Sorry We've Stopped Taking Requests 2 Become 1 Spice Girls, The 10 Min The Karaoke Show Is Over 2 Become One SPICE GIRLS 10 Min Welcome To Karaoke Show 2 Faced Louise 10 Out Of 10 Louchie Lou 2 Find U Jewel 10 Rounds With Jose Cuervo Byrd, Tracy 2 For The Show Trooper 10 Seconds Down Sugar Ray 2 Legit 2 Quit Hammer, M.C. -

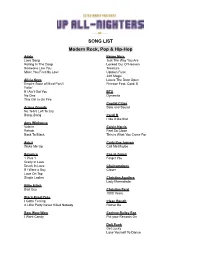

Band Song-List

SONG LIST Modern Rock, Pop & Hip-Hop Adele Bruno Mars Love Song Just The Way You Are Rolling In The Deep Locked Out Of Heaven Someone Like You Treasure Make You Feel My Love Uptown Funk 24K Magic Alicia Keys Leave The Door Open Empire State of Mind Part II Finesse Feat. Cardi B Fallin' If I Ain't Got You BTS No One Dynamite This Girl Is On Fire Capital Cities Ariana Grande Safe and Sound No Tears Left To Cry Bang, Bang Cardi B I like it like that Amy Winhouse Valerie Calvin Harris Rehab Feel So Close Back To Black This is What You Came For Avicii Carly Rae Jepsen Wake Me Up Call Me Maybe Beyonce Cee-lo Green 1 Plus 1 Forget You Crazy In Love Drunk In Love Chainsmokers If I Were a Boy Closer Love On Top Single Ladies Christina Aguilera Lady Marmalade Billie Eilish Bad Guy Christina Perri 1000 Years Black-Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling Clean Bandit A Little Party Never Killed Nobody Rather Be Bow Wow Wow Corinne Bailey Rae I Want Candy Put your Records On Daft Punk Get Lucky Lose Yourself To Dance Justin Timberlake Darius Rucker Suit & Tie Wagon Wheel Can’t Stop The Feeling Cry Me A River David Guetta Love You Like I Love You Titanium Feat. Sia Sexy Back Drake Jay-Z and Alicia Keys Hotline Bling Empire State of Mind One Dance In My Feelings Jess Glynne Hold One We’re Going Home Hold My Hand Too Good Controlla Jessie J Bang, Bang DNCE Domino Cake By The Ocean Kygo Disclosure Higher Love Latch Katy Perry Dua Lipa Chained To the Rhythm Don’t Start Now California Gurls Levitating Firework Teenage Dream Duffy Mercy Lady Gaga Bad Romance Ed Sheeran Just Dance Shape Of You Poker Face Thinking Out loud Perfect Duet Feat. -

Run Date: 08/30/21 12Th District Court Page

RUN DATE: 09/27/21 12TH DISTRICT COURT PAGE: 1 312 S. JACKSON STREET JACKSON MI 49201 OUTSTANDING WARRANTS DATE STATUS -WRNT WARRANT DT NAME CUR CHARGE C/M/F DOB 5/15/2018 ABBAS MIAN/ZAHEE OVER CMV V C 1/01/1961 9/03/2021 ABBEY STEVEN/JOH TEL/HARASS M 7/09/1990 9/11/2020 ABBOTT JESSICA/MA CS USE NAR M 3/03/1983 11/06/2020 ABDULLAH ASANI/HASA DIST. PEAC M 11/04/1998 12/04/2020 ABDULLAH ASANI/HASA HOME INV 2 F 11/04/1998 11/06/2020 ABDULLAH ASANI/HASA DRUG PARAP M 11/04/1998 11/06/2020 ABDULLAH ASANI/HASA TRESPASSIN M 11/04/1998 10/20/2017 ABERNATHY DAMIAN/DEN CITYDOMEST M 1/23/1990 8/23/2021 ABREGO JAIME/SANT SPD 1-5 OV C 8/23/1993 8/23/2021 ABREGO JAIME/SANT IMPR PLATE M 8/23/1993 2/16/2021 ABSTON CHERICE/KI SUSPEND OP M 9/06/1968 2/16/2021 ABSTON CHERICE/KI NO PROOF I C 9/06/1968 2/16/2021 ABSTON CHERICE/KI SUSPEND OP M 9/06/1968 2/16/2021 ABSTON CHERICE/KI NO PROOF I C 9/06/1968 2/16/2021 ABSTON CHERICE/KI SUSPEND OP M 9/06/1968 8/04/2021 ABSTON CHERICE/KI OPERATING M 9/06/1968 2/16/2021 ABSTON CHERICE/KI REGISTRATI C 9/06/1968 8/09/2021 ABSTON TYLER/RENA DRUGPARAPH M 7/16/1988 8/09/2021 ABSTON TYLER/RENA OPERATING M 7/16/1988 8/09/2021 ABSTON TYLER/RENA OPERATING M 7/16/1988 8/09/2021 ABSTON TYLER/RENA USE MARIJ M 7/16/1988 8/09/2021 ABSTON TYLER/RENA OWPD M 7/16/1988 8/09/2021 ABSTON TYLER/RENA SUSPEND OP M 7/16/1988 8/09/2021 ABSTON TYLER/RENA IMPR PLATE M 7/16/1988 8/09/2021 ABSTON TYLER/RENA SEAT BELT C 7/16/1988 8/09/2021 ABSTON TYLER/RENA SUSPEND OP M 7/16/1988 8/09/2021 ABSTON TYLER/RENA SUSPEND OP M 7/16/1988 8/09/2021 ABSTON -

Nurse Aide Employment Roster Report Run Date: 9/24/2021

Nurse Aide Employment Roster Report Run Date: 9/24/2021 EMPLOYER NAME and ADDRESS REGISTRATION EMPLOYMENT EMPLOYMENT EMPLOYEE NAME NUMBER START DATE TERMINATION DATE Gold Crest Retirement Center (Nursing Support) Name of Contact Person: ________________________ Phone #: ________________________ 200 Levi Lane Email address: ________________________ Adams NE 68301 Bailey, Courtney Ann 147577 5/27/2021 Barnard-Dorn, Stacey Danelle 8268 12/28/2016 Beebe, Camryn 144138 7/31/2020 Bloomer, Candace Rae 120283 10/23/2020 Carel, Case 144955 6/3/2020 Cramer, Melanie G 4069 6/4/1991 Cruz, Erika Isidra 131489 12/17/2019 Dorn, Amber 149792 7/4/2021 Ehmen, Michele R 55862 6/26/2002 Geiger, Teresa Nanette 58346 1/27/2020 Gonzalez, Maria M 51192 8/18/2011 Harris, Jeanette A 8199 12/9/1992 Hixson, Deborah Ruth 5152 9/21/2021 Jantzen, Janie M 1944 2/23/1990 Knipe, Michael William 127395 5/27/2021 Krauter, Cortney Jean 119526 1/27/2020 Little, Colette R 1010 5/7/1984 Maguire, Erin Renee 45579 7/5/2012 McCubbin, Annah K 101369 10/17/2013 McCubbin, Annah K 3087 10/17/2013 McDonald, Haleigh Dawnn 142565 9/16/2020 Neemann, Hayley Marie 146244 1/17/2021 Otto, Kailey 144211 8/27/2020 Otto, Kathryn T 1941 11/27/1984 Parrott, Chelsie Lea 147496 9/10/2021 Pressler, Lindsey Marie 138089 9/9/2020 Ray, Jessica 103387 1/26/2021 Rodriquez, Jordan Marie 131492 1/17/2020 Ruyle, Grace Taylor 144046 7/27/2020 Shera, Hannah 144421 8/13/2021 Shirley, Stacy Marie 51890 5/30/2012 Smith, Belinda Sue 44886 5/27/2021 Valles, Ruby 146245 6/9/2021 Waters, Susan Kathy Alice 91274 8/15/2019 -

B. Slade Courage Award

B. Slade Courage Award With a career spanning over 20 years, B. Slade has never shied away from using his musical gifts to move gospel, soul and rock audiences. Whether writing a song about a mother losing her sons during Hurricane Sandy or scoring the music for television shows or series, B. Slade’s musical efforts have blended styles, including pop, R&B, soul, funk, rock, latin punk and trance to create sounds that are distinctly his. His courage to speak his truth about his sexuality has not dimmed his talent or the desire of many to collaborate with this musical wonder. Born and raised in San Diego, California, B. Slade early life was filled with music; mostly gospel but also infused with R&B, funk and soul. B. Slade recorded his first album at 10 and at 24, his performance at the 14th Annual Stellar Awards received critical acclaim and helped make him a fixture among young urban gospel music lovers. Since then, he has released several hundred songs on over 30 albums, while producing several others for both gospel and secular artists. He has won 7 Stellar Awards, a GMA Award and received 3 Grammy nominations – one for Best Soul Gospel Album for his 2004 gold album, Out The Box, another in 2009 for Best Urban/Soul Alternative Performance for his single, "Blend" from his 2009 mainstream album, "Unspoken", and a 3rd in 2014 for writing and co-producing Angie Fisher's debut hit single, "I.R.S.", which received a nomination for "Best Traditional R&B performance. -

PLJ November 23 2020 November 23, 2020

Monday, November 23, 2020 Pittsburgh Legal Journal • 5 SA-0000950-20 ; Comm. of PA vs of 2020. Lori Abrams, Admrx., c/o Michael I. Baird, Barbara Ann a/k/a Barbara A. Keller, Donald G. a/k/a Donald Keller, Ora Johnson; P-atty: Criminal Divi - LEGAL ADS Werner, Esq., Goldblum Sablowsky, LLC, 285 Baird, deceased, of Franklin Park Borough, deceased, of Ross Township, PA. No. 05745 of sion Allegheny County District E. Waterfront Drive, Suite 160, Homestead, PA PA. No. 05620 of 2020. John E. Baird, Extr., 2020. Mary Katherine Hobbs, Extrx., 41 15120. 2231 McAleer Road, Sewickley, PA 15143 or to Chalfonte Ave., Pittsburgh, PA 15229 or to Attorney’s Office 20-04339 Nov 23, 30; Dec 7, 2020 Charles F. Perego, Esq., McMonigle, Vesely & Harold A. English, Esq., H.A. English & SA-0001046-20 ; Comm. of PA vs David Legal notices that are published Perego, P.C., 694 Lincoln Ave., Pittsburgh, PA Associates, P.C., 4290 William Flinn Highway, Business LLC; P-atty: Criminal in the Pittsburgh Legal Journal Hill, Marlee Anne, deceased, of 15202. Suite 200, Allison Park, PA 15101. Division Allegheny County District are done so pursuant to Title 45 McKeesport, PA. No. 03131 of 2020. Melanie 20-04291 Nov 16, 23, 30, 2020 20-04318 Nov 16, 23, 30, 2020 Boros, Admrx., 1707 Patterson Street, Attorney’s Office Pa. Code 101 et seq. and various local court rules. The Pittsburgh McKeesport, PA 15132 or to Mallory L. Sikora, Bednar, Ellen L. a/k/a Ellen Lenore MacDonald, George Frederick a/k/a SA-0001068-20 ; Comm. -

Jukebox Oldies

JUKEBOX OLDIES – MOTOWN ANTHEMS Disc One - Title Artist Disc Two - Title Artist 01 Baby Love The Supremes 01 I Heard It Through the Grapevine Marvin Gaye 02 Dancing In The Street Martha Reeves & The Vandellas 02 Jimmy Mack Martha Reeves & The Vandellas 03 Reach Out, I’ll Be There Four Tops 03 You Keep Me Hangin’ On The Supremes 04 Uptight (Everything’s Alright) Stevie Wonder 04 The Onion Song Marvin Gaye & Tammi Terrell 05 Do You Love Me The Contours 05 Got To Be There Michael Jackson 06 Please Mr Postman The Marvelettes 06 What Becomes Of The Jimmy Ruffin 07 You Really Got A Hold On Me The Miracles 07 Reach Out And Touch Diana Ross 08 My Girl The Temptations 08 You’re All I Need To Get By Marvin Gaye & Tammi Terrell 09 Where Did Our Love Go The Supremes 09 Reflections Diana Ross & The Supremes 10 I Can’t Help Myself Four Tops 10 My Cherie Amour Stevie Wonder 11 The Tracks Of My Tears Smokey Robinson & The Miracles 11 There’s A Ghost In My House R. Dean Taylor 12 My Guy Mary Wells 12 Too Busy Thinking About My Marvin Gaye 13 (Love Is Like A) Heatwave Martha Reeves & The Vandellas 13 The Happening The Supremes 14 Needle In A Haystack The Velvelettes 14 It’s A Shame The Spinners 15 It’s The Same Old Song Four Tops 15 Ain’t No Mountain High Enough Diana Ross 16 Get Ready The Temptations 16 Ben Michael Jackson 17 Stop! (in the name of love) The Supremes 17 Someday We’ll Be Together Diana Ross & The Supremes 18 How Sweet It Is Marvin Gaye 18 Ain’t Too Proud To Beg The Temptations 19 Take Me In Your Arms Kim Weston 19 I’m Still Waiting Diana Ross 20 Nowhere To Run Martha Reeves & The Vandellas 20 I’ll Be There The Jackson 5 21 Shotgun Junior Walker & The All Stars 21 What’s Going On Marvin Gaye 22 It Takes Two Marvin Gaye & Kim Weston 22 For Once In My Life Stevie Wonder 23 This Old Heart Of Mine The Isley Brothers 23 Stoned Love The Supremes 24 You Can’t Hurry Love The Supremes 24 ABC The Jackson 5 25 (I’m a) Road Runner JR.