A Brief Guide to the Dutch Election: Will the Rise of Populism Continue Into 2017?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

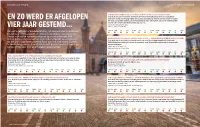

En Zo Werd Er De Afgelopen Vier Jaar Gestemd

UITKERINGSGERECHTIGDEN TWEEDE KAMER VERKIEZINGEN EEN INKOMENSAANVULLING VOOR MENSEN MET EEN MEDISCHE URENBEPERKING Deze motie beoogde te bereiken dat mensen met een beperking/handicap die naar hun maximale EN ZO WERD ER AFGELOPEN vermogen werken, een toeslag krijgen die los staat van eventueel inkomen van een partner of ouders. Dit omdat zij vanwege die medische urenbeperking dus maar een beperkt aantal uren kunnen werken en zodoende onvoldoende inkomen kunnen genereren. Stemdatum: 24 september 2019 VIER JAAR GESTEMD… Indiener: Jasper van Dijk (SP) Van extra geld voor armoedebestrijding, tot aanpassingen in de Wajong. 50PLUS CDA CU D66 DENK FvD GL PvdA PvdD PVV SGP SP VVD De afgelopen vier jaar heeft de Tweede Kamer kunnen stemmen over diverse voorstellen ter verbetering van de sociale zekerheid. FNV Uitkeringsgerechtigden heeft er acht moties uitgepikt. Groen betekent AANPASSEN WETSVOORSTEL WAJONG OM DE REGELS TE HARMONISEREN ZONDER VERSLECHTERING Deze motie was bedoeld om het alternatief zoals opgesteld door belangenorganisaties (onder wie dat een partij voor heeft gestemd. Rood was een stem tegen. Duidelijk FNV Uitkeringsgerechtigden) in de wet te verwerken, zodat de nadelige gevolgen van de harmonisatie te zien is dat geen van de moties het heeft gehaald omdat de regerings- worden voorkomen. partijen (VVD, CDA, D66 en CU) steeds tegenstemden. Stemdatum: 30 oktober 2019 Indieners: PvdA, GL, SP en 50Plus 50PLUS CDA CU D66 DENK FvD GL PvdA PvdD PVV SGP SP VVD EEN AANGESCHERPT AFSLUITINGSBELEID VOOR DRINKWATER EN WIFI Deze motie was opgesteld om naast gas en elektriciteit ook drinkwater en internet op te nemen als basis- voorziening. Dit om te voorkomen dat mensen met een betalingsachterstand in een onleefbare situatie EXTRA GELD OM DE GEVOLGEN VAN ARMOEDE ONDER KINDEREN TE BESTRIJDEN belanden als deze voorzieningen worden afgesloten. -

I&O-Zetelpeiling 15 Maart 2021

Rapport I&O-Zetelpeiling 15 maart 2021 VVD levert verder in; D66 stijgt door; Volt en Ja21 maken goede kans Colofon Maart peiling #2 I&O Research Uitgave I&O Research Piet Heinkade 55 1019 GM Amsterdam Rapportnummer 2021/69 Datum maart 2021 Auteurs Peter Kanne Milan Driessen Het overnemen uit deze publicatie is toegestaan, mits de bron (I&O Research) duidelijk wordt vermeld. 15 maart 2021 2 van 15 Inhoudsopgave Belangrijkste uitkomsten _____________________________________________________________________ 4 1 I&O-zetelpeiling: VVD levert verder in ________________________________________________ 7 VVD levert verder in, D66 stijgt door _______________________ 7 Wie verliest aan wie en waarom? _________________________ 9 Aandeel zwevende kiezers _____________________________ 11 Partij van tweede (of derde) voorkeur_______________________ 12 Stemgedrag 2021 vs. stemgedrag 2017 ______________________ 13 2 Onderzoeksverantwoording _________________________________________________________ 14 15 maart 2021 3 van 15 Belangrijkste uitkomsten VVD levert verder in; D66 stijgt door; Volt en Ja21 maken goede kans In de meest recente I&O-zetelpeiling – die liep van vrijdag 12 tot maandagochtend 15 maart – zien we de VVD verder inleveren (van 36 naar 33 zetels) en D66 verder stijgen (van 16 naar 19 zetels). Bij peilingen (steekproefonderzoek) moet rekening gehouden worden met onnauwkeurigheids- marges. Voor VVD (21,0%, marge 1,6%) en D66 (11,8%, marge 1,3%) zijn dat (ruim) 2 zetels. De verschuiving voor D66 is statistisch significant, die voor VVD en PvdA zijn dat nipt. Als we naar deze zetelpeiling kijken – 2 dagen voor de verkiezingen – valt op hoezeer hij lijkt op de uitslag van de Tweede Kamerverkiezingen van 2017. Van de winst die de VVD boekte in de coronacrisis is niets over: nu 33 zetels, vier jaar geleden ook 33 zetels. -

Roelof Bisschop Van De SGP Ronald Van Raak Van De SP

Met stijgende verontwaardiging en teleurstelling hoorde ik op dinsdag 17 april 2018 in de Tweede Kamer het debat aan over het wetsvoorstel herindeling Groningen, Haren en Ten Boer. Dinsdag 17 april 2018 was ik aanwezig in Den Haag bij het debat over het wetsvoorstel herindeling Groningen, Haren en Ten Boer. Ik was daar in goed gezelschap van veel Harenaars. Het debat begon om 18.45 uur (een kwartier later dan gepland) en eindigde ruim na 22.00 uur. In Haren de Krant stond aan het einde van de avond al een zeer uitgebreid verslag van de vergadering. In de pauze na de eerste termijn van de Kamer werd mij een aantal keer gevraagd: Heb je je lidmaatschap van D66 al opgezegd? De dagen na het debat werd mij veelvuldig gevraagd: Op wie moet ik nu dan stemmen? Het debat leverde een ontgoocheld gevoel op. Maar ook boosheid en verdriet. De middenpartijen in dit land die graag het vertrouwen willen terugwinnen van een groot deel van het publiek hebben schromelijk gefaald. Samen met de minister is er flink bijgedragen aan de afkalving van het vertrouwen in de politiek. En hebben daarmee de deur opengezet voor Harenaars om de flanken van het politieke spectrum ernstig te overwegen. Roelof Bisschop van de SGP Roelof Bisschop van de SGP opende de lijst van sprekers van de zijde van de Kamer. Hij noemde een aantal duidelijke uitgangspunten om daar vervolgens het voorstel van de minister aan te toetsen. Een degelijke aanpak die helaas niet veel navolging kreeg. Bisschop moest in zijn tweede termijn teleurgesteld constateren dat de minister geen enkele poging heeft gedaan om te reageren op de opbouw van zijn verhaal. -

Programme of Special Events Monday 3 November 2014 5

CAN YOUTH REVITALISE DEMOCRACY? 3 TO 9 NOVEMBERPROGRAMME 2014 world-forum-democracy.org OF SPECIAL EVENTS FOR THE SCHOOLS OF POLITICAL STUDIES FROM 3 TO 7 NOVEMBER 2014 SCHOOLS OF POLITICAL STUDIES 2 OVERALL FORUM STRUCTURE OVERALL FORUM STRUCTURE 3 FORUM CORE PROGRAMME SPS SPECIAL PROGRAMME Monday 3/11 Tuesday 4/11 Wednesday 5/11 Thursday 6/11 Friday 7/11 9.00-11.00 SPECIAL EVENTS THEMATIC GROUP MEETING 9.30-10.30 9.00-10.00 FOR THE UKRAINIAN VISITS TO THE ECtHR VISITS TO THE ECtHR SCHOOL 10.00-11.30 MEETING WITH ARAB YOUTH 11.30-12.30 AM PLENARY SESSION V4 MEETS EASTERN AND LABS SERIES 1 PARTNERSHIP 10.30-12.30 10.30-12.30 REPORTING AND PROFESSIONAL 9.30-11.00 9.30-10.30 CLOSING SESSION GROUP MEETINGS VISIT TO THE ECtHR VISITS TO THE ECtHR 11.00-12.00 VISITS TO THE ECtHR Reception, Break Self-service restaurant, EP Lunch, EP Free Free Lobby of the Hemicycle 14.00-14.15 FAMILY PHOTO 14.30-15.30 LABS SERIES 2 VISITS TO THE ECtHR 14.30-16.30 14.30-15.00 THEMATIC DIPLOMA CEREMONY 14.00-16.00 GROUP MEETINGS MEETING PM ON THE SITUATION 17.00-18.00 IN UKRAINE 16.00 – 18.45 BILATERAL MEETINGS 15.30-16.30 OFFICIAL OPENING UN-CONFERENCES VISITS TO THE ECtHR OF THE WORLD FORUM Reception at Reception at Evening Free Free Free the “Maison de l’Alsace” the “Orangerie” 4 PROGRAMME OF SPECIAL EVENTS MONDAY 3 NOVEMBER 2014 5 SCHOOLS OF POLITICAL STUDIES AT THE ALL DAY MEETINGS WITH JUDGES/LAWYERS OF THE ECtHR EUROPEAN COURT OF HUMAN RIGHTS (ECtHR) WORLD FORUM FOR DEMOCRACY All Schools’ participants Please consult the timetable on pages 14 and 15. -

The EU Lobby of the Dutch Provinces and Their

The EU lobby of the Dutch provinces and their ‘House of the Dutch Provinces’ regions An analysis on the determinants of the adopted paradiplomacy strategy of Dutch provinces vis-à-vis the national level Diana Sisto (460499) MSc International Public Management and Policy Master thesis First reader: dr. A.T. Zhelyazkova Second reader: dr. K. H. Stapelbroek Word Count: 24951 Date: 25-07-2018 Summary This thesis contains a case study on the determinants that influence the paradiplomacy strategy that Dutch provinces adopt vis-à-vis their member state, when representing their European interest. Because of the growing regional involvement in International Affairs, the traditional relationship between the sub-national authorities and their member states has been challenged. Both the sub- national and national level have been transitioning into a new role. This thesis aimed to contribute to the literature on determinants of paradiplomacy strategies (cooperative, conflicting and non-interaction paradiplomacy) that sub-national actors can adopt vis-à-vis their member state. The goal of the research is twofold: a) to gain insights in the reason why Dutch regions choose to either cooperative, conflicting or non-interaction paradiplomacy in representing their EU interests vis-à-vis the national level and b) to determine which strategies are most used and why. Corresponding to this goal the main research question is “Which determinants influence the paradiplomacy strategy that Dutch provinces adopt vis- à-vis their member state, when representing their European interests?” To answer the research question a qualitative in depth case study has been performed on two cases consisting of two House of the Dutch provinces regions and their respective provinces. -

Prinsjesdagpeiling 2017

Rapport PRINSJESDAGPEILING 2017 Forum voor Democratie wint terrein, PVV zakt iets terug 14 september 2017 www.ioresearch.nl I&O Research Prinsjesdagpeiling september 2017 Forum voor Democratie wint terrein, PVV zakt iets terug Als er vandaag verkiezingen voor de Tweede Kamer zouden worden gehouden, is de VVD opnieuw de grootste partij met 30 zetels. Opvallend is de verschuiving aan de rechterflank. De PVV verliest drie zetels ten opzichte van de peiling in juni en is daarmee terug op haar huidige zetelaantal (20). Forum voor Democratie stijgt, na de verdubbeling in juni, door tot 9 zetels nu. Verder zijn er geen opvallende verschuivingen in vergelijking met drie maanden geleden. Zes op de tien Nederlanders voor ruimere bevoegdheden inlichtingendiensten Begin september werd bekend dat een raadgevend referendum over de ‘aftapwet’ een stap dichterbij is gekomen. Met deze wet krijgen Nederlandse inlichtingendiensten meer mogelijkheden om gegevens van internet te verzamelen, bijvoorbeeld om terroristen op te sporen. Tegenstanders vrezen dat ook gegevens van onschuldige burgers worden verzameld en bewaard. Hoewel het dus nog niet zeker is of het referendum doorgaat, heeft I&O Research gepeild wat Nederlanders nu zouden stemmen. Van de kiezers die (waarschijnlijk) gaan stemmen, zijn zes op de tien vóór ruimere bevoegdheden van de inlichtingendiensten. Een kwart staat hier negatief tegenover. Een op de zes kiezers weet het nog niet. 65-plussers zijn het vaakst voorstander (71 procent), terwijl jongeren tot 34 jaar duidelijk verdeeld zijn. Kiezers van VVD, PVV en de christelijke partijen CU, SGP en CDA zijn in ruime meerderheid voorstander van de nieuwe wet. Degenen die bij de verkiezingen in maart op GroenLinks en Forum voor Democratie stemden, zijn per saldo tegen. -

2019 © Timbro 2019 [email protected] Layout: Konow Kommunikation Cover: Anders Meisner FEBRUARY 2019

TIMBRO AUTHORITARIAN POPULISM INDEX 2019 © Timbro 2019 www.timbro.se [email protected] Layout: Konow Kommunikation Cover: Anders Meisner FEBRUARY 2019 ABOUT THE TIMBRO AUTHORITARIAN POPULISM INDEX Authoritarian Populism has established itself as the third ideological force in European politics. This poses a long-term threat to liberal democracies. The Timbro Authoritarian Populism Index (TAP) continuously explores and analyses electoral data in order to improve the knowledge and understanding of the development among politicians, media and the general public. TAP contains data stretching back to 1980, which makes it the most comprehensive index of populism in Europe. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY • 26.8 percent of voters in Europe – more than one in four – cast their vote for an authoritarian populist party last time they voted in a national election. • Voter support for authoritarian populists increased in all six elections in Europe during 2018 and has on an aggregated level increased in ten out of the last eleven elections. • The combined support for left- and right-wing populist parties now equals the support for Social democratic parties and is twice the size of support for liberal parties. • Right-wing populist parties are currently growing more rapidly than ever before and have increased their voter support with 33 percent in four years. • Left-wing populist parties have stagnated and have a considerable influence only in southern Europe. The median support for left-wing populist in Europe is 1.3 percent. • Extremist parties on the left and on the right are marginalised in almost all of Europe with negligible voter support and almost no political influence. -

European Populism in the European Union

H Balnaves, E Monteiro Burkle, J Erkan & D Fischer ‘European populism in the European Union: Results and human rights impacts of the 2019 parliamentary elections’ (2020) 4 Global Campus Human Rights Journal 176-200 http://doi.org/20.500.11825/1695 European populism in the European Union: Results and human rights impacts of the 2019 parliamentary elections Hugo Balnaves,* Eduardo Monteiro Burkle,** Jasmine Erkan*** and David Fischer**** Abstract: Populism is a problem neither unique nor new to Europe. However, a number of crises within the European Union, such as the ongoing Brexit crisis, the migration crisis, the climate crisis and the rise of illiberal regimes in Eastern Europe, all are adding pressure on EU institutions. The European parliamentary elections of 2019 saw a significant shift in campaigning, results and policy outcomes that were all affected by, inter alia, the aforementioned crises. This article examines the theoretical framework behind right-wing populism and its rise in Europe, and the role European populism has subversively played in the 2019 elections. It examines the outcomes and human rights impacts of the election analysing the effect of right-wing populists on key EU policy areas such as migration and climate change. Key Words: European parliamentary elections; populism; EU institutions; human rights * LLB (University of Adelaide) BCom (Marketing) (University of Adelaide); EMA Student 2019/20. ** LLB (State University of Londrina); EMA Student 2019/20. *** BA (University of Western Australia); EMA Student 2019/20. **** MA (University of Mainz); EMA Student 2019/20. European populism in the European Union 177 1 Introduction 2019 was a year fraught with many challenges for the European Union (EU) as it continued undergoing several crises, including the ongoing effects of Brexit, the migration crisis, the climate crisis and the rise of illiberal regimes in Eastern Europe. -

Het Is Heel Menselijk Zich Iets Niet Te Herinneren

Het is heel menselijk zich iets niet te herinneren Door J.M.C.M. Smarius - 10 april 2021 Geplaatst in Omtzigtdebat Opa, wat vond je van dat debat over ‘positie Omtzigt functie elders’? “Langdradig tweederangs circus met deelnemers aan de circusvoorstelling die uiteindelijk zichzelf vaak in de vingers snijden door de indruk achter te laten niet goed genoeg te zijn om mee te doen.” Hoezo? “Deelnemers die tot treurnis toe alsmaar herhalen dat iemand liegt, zonder ook maar een poging te doen tot aannemelijke onderbouwing van deze beschuldiging. En die het zich niet herinneren van iets meteen bestempelen als een bewijs dat iemand niet meer geschikt is voor een bepaalde taak, aldus blijk gevend van een volslagen onbegrip van het begrip zich herinneren.” Een hele mond vol. Wat bedoel je met onbegrip van het begrip zich herinneren? “Mensen hebben het vermogen herinneringen die ons kunnen afleiden selectief te vergeten. Ratten Wynia's week: Het is heel menselijk zich iets niet te herinneren | 1 Het is heel menselijk zich iets niet te herinneren hebben dat vermogen ook. Dat blijkt uit een studie van de University of Cambridge. De ontdekking dat ratten en mensen een gemeenschappelijk actief vermogen om te vergeten delen wijst erop dat dit vermogen een essentiële rol speelt in de aanpassing van zoogdieren aan hun leefomgeving, en dat het waarschijnlijk minstens teruggaat tot de tijd waarin de gemeenschappelijke voorouder van ratten en mensen leefde, zo’n 100 miljoen jaar geleden. Geschat wordt dat het menselijk brein 86 miljard neuronen of hersencellen bevat, en wel 150 biljoen synaptische verbindingen, wat van het brein een krachtige machine maakt om herinneringen te verwerken, op te slaan. -

Van Fatwa Tot Fitna Een Onderzoek Naar De Berichtgeving Van NRC Handelsblad Over De Islam Tussen 1995 En 2009

Van Fatwa tot Fitna Een onderzoek naar de berichtgeving van NRC Handelsblad over de islam tussen 1995 en 2009 Erasmus Universiteit Rotterdam Erasmus School of History, Culture and Communication (ESHCC) Media & Journalistiek Masterthesis Jennifer van Genderen (314951) Begeleider: Dr. Chris Aalberts Tweede lezer: Drs. Louis Zweers januari 2011 Foto omslag: © Peter Hilz B.V. Rotterdam, 01 maart 2010, Stadsgezicht Mevlana Moskee Rotterdam-West Abstract Since the September 11th attacks by al-Qaeda on the US Islam and Muslims are increasingly associated with violence and terrorism. This trend is also evident in the Netherlands: the coverage of Islam and Muslims in the Netherlands has grown exponentially. This observation as resulted in the following central question: Has the news coverage of Islam in NRC Handelsblad changed between 1995 and 2009? This question have been researched by using quantitative content analysis. For the analysis I have chosen articles published in 1995, 2002 and 2009 in the Dutch newspaper NRC Handelsblad. The choice for these years is based on the assumption that there might be differences in news coverage of Islam, given the harsh criticism of Islam and Muslims by Dutch politicians and the public. The analysis of the news coverage shows a clear development of newsworthiness, media hype and framing of issues related to Islam and Muslims in the Netherlands. Islam is a subject that is connected with a large number of themes. The analysis of the term Islamization shows that in 1995 this term was associated with Islam abroad only. The analysis in 2002 and 2009 shows that this term has become commonplace in political debates in NRC Handelsblad. -

NPO Begroting 2019 – Definitief Onopgemaakte Versie

NPO Begroting 2019 – Definitief onopgemaakte versie Gehanteerde definities De NPO (Nederlandse Publieke Omroep) Het geheel van bestuur en alle landelijke publieke omroepen van de landelijke publieke omroep; omroepverenigingen, taakomroepen én NPO-organisatie. Wanneer we spreken over de Nederlandse Publieke Omroep (NPO) omvatten we dus zowel omroepen als de NPO-organisatie, die ieder vanuit hun eigen taak verantwoordelijk zijn voor de uitvoering van de publieke mediaopdracht op landelijk niveau. De omroepen zijn dat door de verzorging van media-aanbod en de NPO-organisatie omdat deze het samenwerkings- en sturingsorgaan is voor de uitvoering van de publieke mediaopdracht op landelijk niveau, zoals bedoeld in artikel 2.2 en 2.3 MW. Hier worden nadrukkelijk niet de lokale en regionale omroepen bedoeld. Omroepen Alle landelijke publieke omroepen; de omroeporganisaties en taakomroepen. Wanneer er respectievelijk lokale, regionale of commerciële omroepen bedoeld worden, zal dat expliciet vermeld worden. NPO-organisatie of NPO (zonder de) Het samenwerkings- en bestuursorgaan van de NPO; de Stichting Nederlandse Publieke Omroep. Inhoud Inleiding 1. Financieel kader en budgetaanvraag 2. Aanbod 3. Kanalen 4. Publiek en partners 5. NPO-organisatie 6. Programmatische bijdragen omroepen Bijlage 1 Overzicht aanbodkanalen Bijlage 2 Aanvraag beëindiging aanbodkanalen Bijlage 3 Overzicht acties CBP en acties Begrotingen Bijlage 4 Toelichting begroting SOM 1 Inleiding Het gaat - nog - goed met de landelijke publieke omroep. Met aanzienlijk minder middelen en menskracht dan voorheen hebben we de afgelopen jaren aangetoond dat we in de ogen van ons publiek een belangrijke factor in de samenleving zijn. Ook in 2019 willen we die rol blijven vervullen. We willen ons journalistieke aanbod versterken door nieuwe concepten te introduceren en we blijven investeren in de publieke waarde van ons aanbod. -

The Rise of Kremlin-Friendly Populism in the Netherlands

CICERO FOUNDATION GREAT DEBATE PAPER No. 18/04 June 2018 THE RISE OF KREMLIN-FRIENDLY POPULISM IN THE NETHERLANDS MARCEL H. VAN HERPEN Director The Cicero Foundation Cicero Foundation Great Debate Paper No. 18/04 © Marcel H. Van Herpen, 2018. ISBN/EAN 978-90-75759-17-4 All rights reserved The Cicero Foundation is an independent pro-Atlantic and pro-EU think tank, founded in Maastricht in 1992. www.cicerofoundation.org The views expressed in Cicero Foundation Great Debate Papers do not necessarily express the opinion of the Cicero Foundation, but they are considered interesting and thought-provoking enough to be published. Permission to make digital or hard copies of any information contained in these web publications is granted for personal use, without fee and without formal request. Full citation and copyright notice must appear on the first page. Copies may not be made or distributed for profit or commercial advantage. 2 The Rise of Kremlin-Friendly Populism in the Netherlands Marcel H. Van Herpen EARLY POPULISM AND THE MURDERS OF FORTUYN AND VAN GOGH The Netherlands is known as a tolerant and liberal country, where extremist ideas – rightwing or leftwing – don’t have much impact. After the Second World War extreme right or populist parties played only a marginal role in Dutch politics. There were some small fringe movements, such as the Farmers’ Party ( Boerenpartij ), led by the maverick “Boer Koekoek,” which, in 1967, won 7 seats in parliament. In 1981 this party lost its parliamentary representation and another party emerged, the extreme right Center Party ( Centrum Partij ), led by Hans Janmaat.